September 30, 2016 marked a grim 40th anniversary for abortion access in the United States: On that day in 1976, Congress first passed the Hyde Amendment (named for the late Rep. Henry Hyde of Illinois). Proposed as a response to Roe v. Wade, the Hyde Amendment is most known for its devastating impact on millions of low-income women and families because it essentially bars federal abortion coverage through the Medicaid program. But the impact of the Hyde Amendment is not limited to Medicaid enrollees; it also restricts abortion coverage for women insured through Medicare and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

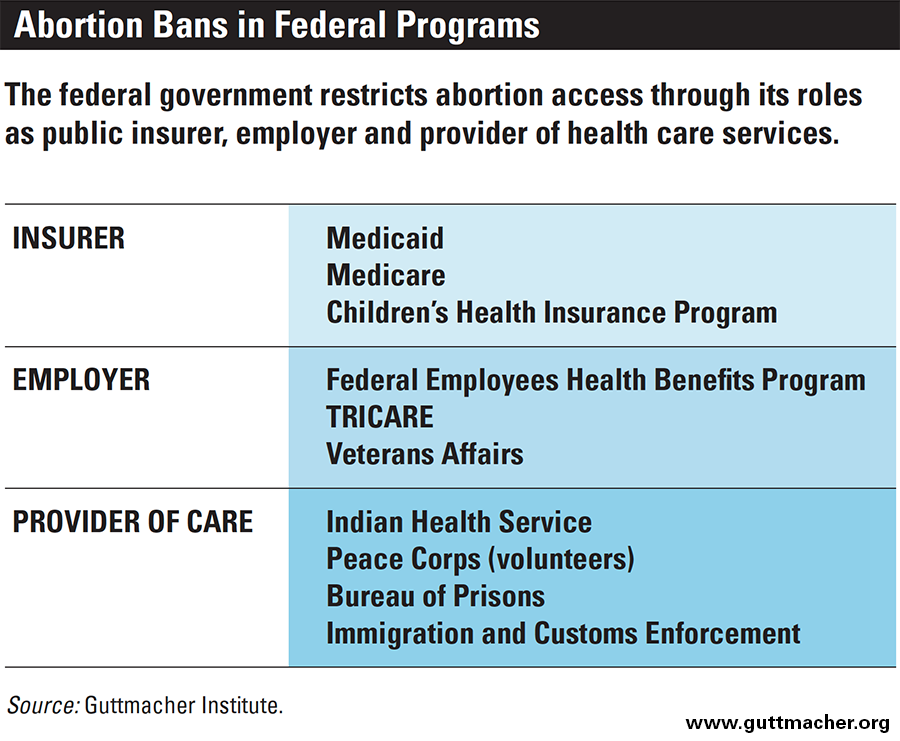

In addition, Congress and the executive branch have used the Hyde Amendment as a model to further limit access to abortion by creating analogous restrictions for people who obtain their health care or coverage through the federal government in other ways. This includes: federal employees and their dependents; military personnel and their dependents; veterans; Peace Corps volunteers; American Indians and Alaska Natives; people held in federal prisons or detention centers; and low-income women in the District of Columbia (see chart). The Hyde Amendment and many (though not all) of these restrictions are built into annual spending bills, which must be renewed by Congress each year.

As supporters of abortion rights prepare for an antiabortion Trump administration and Congress, they must be ready to respond to aggressive efforts to roll back abortion access, including attempts to apply abortion coverage restrictions to new populations and to permanently ban federal spending for abortion coverage and care altogether. In the midst of such policy debates, advocates and policymakers must not lose sight of the women and families at the heart of it all, a disproportionate number of whom are low-income women and women of color.

Enrollees in Federal Insurance Programs

The federal government plays a major role as an insurance provider for millions of people across the country enrolled in the Medicaid, Medicare and CHIP programs. Medicaid is a joint federal-state health insurance program for eligible low-income individuals. Its sister program, CHIP, extends coverage to children and adolescents up to age 19 of families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to afford private insurance. Medicare, on the other hand, is typically known as the federal health insurance program for people who are 65 or older. Nevertheless, women of reproductive age with disabilities or end-stage renal disease are also covered by Medicare.

Together, these three programs represent a significant safety net for women and families, enabling them to access critical health care services that would otherwise remain out of reach. Yet, the majority of women of reproductive age enrolled in these programs are affected by the Hyde Amendment, which carves abortion care out of the package of benefits to which they have access. (Congress also included the abortion coverage ban for CHIP in statutory language when it created the program in 1997.)

Low-income Women

Although the Hyde Amendment bars federal funds from being used to provide coverage of abortion under Medicaid and CHIP, states have the option of using their own nonfederal funds to provide abortion coverage to enrollees. Seventeen states have a policy (either voluntarily or by court order) requiring the state to cover abortion for people enrolled in Medicaid, but just 15 appear to be doing so in practice.1 Some, but not all, of these policies extend coverage to CHIP enrollees. In addition, because Congress exercises oversight over the District of Columbia’s spending, it has taken the Hyde Amendment one step further and currently prohibits the District from using its own nonfederal funds to provide abortion coverage.

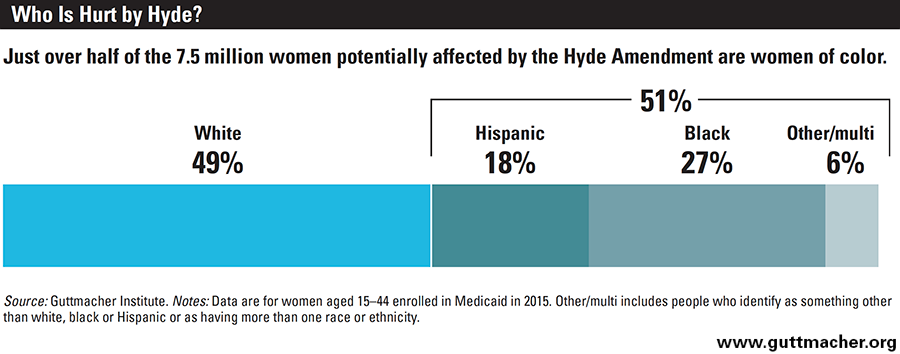

For Medicaid and CHIP enrollees, this means that access to affordable abortion care is dependent on where they live. Of women aged 15–44 enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP nationwide in 2015, 58% lived in the 35 states and the District of Columbia that do not cover abortion except in limited circumstances.2 This amounted to roughly 7.5 million women of reproductive age, including 3.5 million living below the federal poverty level.

In states that do not extend coverage beyond the limits of the Hyde Amendment, a woman whose income is at the Medicaid eligibility ceiling would need to pay nearly a third of her entire family income for a month for an abortion at 10 weeks of pregnancy.3 (An abortion at 10 weeks costs an average of $500, and the average Medicaid ceiling for a family of three for a month in these states is $1,566.)

Advocates and policymakers must not lose sight of the people who stand to be harmed the most by new restrictions on abortion access.

Women of color, in particular, bear the brunt of the Hyde Amendment’s harmful impact. Because of social and economic inequality linked to racism and discrimination, women of color are disproportionately likely to be insured by the Medicaid program: Thirty-one percent of black women aged 15–44 and 27% of Hispanic women of the same age were enrolled in Medicaid in 2015, compared with 15% of white women.6 And just over half of the 7.5 million women of reproductive age with Medicaid coverage in states that do not cover abortion were women of color (see chart).2

Women with Disabilities

In 1998, Congress updated the language of the Hyde Amendment to ensure that it would bar abortion coverage for women enrolled in Medicare. In 2015, there were approximately 907,000 women of reproductive age insured through Medicare.2 As a group, people with disabilities already face a history of stigma and oppression when it comes to their sexual and reproductive autonomy. Finding accessible and culturally competent sexual and reproductive health information and care can be particularly challenging, even without the added financial burden of an abortion coverage ban.7,8

In 2015, 264,000 women of reproductive age enrolled in Medicare identified it as their only source of insurance (see chart).2 The remaining 643,000 women of reproductive age enrolled in Medicare reported having another source of coverage; typically, these women are dually eligible and enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid because they are low-income women living with a disability. While both programs provide a critical safety net for these women, the federal government’s policy of withholding abortion coverage through Medicaid and Medicare places an enormous financial obstacle in front of women for whom access to services may already be severely lacking.

Federal Employees

The federal government arranges and provides insurance coverage for more than 20 million Americans every year through the Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) Program for civilian employees as well as various programs providing coverage or care to eligible military personnel, veterans and their families.

Civilian Employees and Their Dependents

The FEHB Program is reportedly the largest employer-sponsored insurance program in the world, covering more than eight million people, including federal employees, retirees and family members.9 Congress first imposed a ban on abortion coverage in the FEHB Program in 1983. At the time, the only exception to the ban was for cases of life endangerment; current policy is in line with the Hyde Amendment, restricting coverage to cases of life endangerment or pregnancies resulting from rape or incest. As of November 2016, some 335,000 women of reproductive age were primary FEHB policyholders, and an unknown number more enrolled as dependents.10

Military Personnel and Their Dependents

TRICARE—the health insurance program administered by the Department of Defense—covers nearly 9.4 million uniformed service personnel, retirees and their family members.11 Congress first imposed an abortion coverage ban on the program in 1978 and made the ban permanent in 1984. Currently, abortion coverage is prohibited except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. This restriction applies to the 1.4 million women of reproductive age—both military servicewomen and dependents—receiving their coverage through TRICARE in 2015.2 For 900,000 of these women, TRICARE was their only source of insurance.

In addition, current law prohibits the performance of abortions in military facilities, even if paid for privately, except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. These restrictions jeopardize the health and safety of women who are among the more than 277,000 military personnel stationed overseas.12 For many, military health facilities are the only source of safe, high-quality health care, particularly in countries where abortion is illegal in all or most cases, such as Afghanistan and Iraq.13 Because most women cannot obtain an abortion in a military hospital even if they pay for it themselves, their only options are to try to make expensive arrangements to obtain a safe abortion in another country or to risk unsafe conditions in-country. For some women, these restrictions operate as a total ban on abortion care.

Veterans

Approximately 6.7 million eligible veterans receive hospital care and outpatient services through the health care system operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).14 In 1992, Congress passed the Veterans Health Care Act, which, among other things, prohibited the VA from offering abortion care. Under current regulations, the medical benefits package available to veterans cannot include abortion under any circumstances.15 This policy restricts the care available to the 257,000 female veterans of reproductive age who reported in 2015 that they receive VA care, of whom 74,000 identified the VA as their only source of insurance.2

In addition, dependents and survivors of certain veterans are eligible for the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (CHAMPVA), which shares the cost of covered health services and supplies. Although the covered services are supposed to be the same or similar to those received by military personnel, CHAMPVA currently covers abortion only in cases of life endangerment.16,17

Federal Health Care Programs

The federal government is also a direct provider of health care to people participating in or detained by various federal programs, such as the Indian Health Service (IHS), Peace Corps, Federal Bureau of Prisons, and Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

American Indians and Alaska Natives

The IHS is an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services that provides federal health care services to approximately 2.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives through a network of IHS and tribally operated facilities.18 When an abortion spending ban was first imposed on IHS via federal regulation in 1982, it limited spending to cases of life endangerment (in alignment with the version of the Hyde Amendment in effect at that time). Since 1988, the law authorizing federal spending for IHS has required its policy to adhere to the Hyde Amendment. As a result, abortion care is currently available in the limited cases of life endangerment, rape or incest.

None of the 345,000 women of reproductive age who in 2015 reported being insured through IHS identified it as their only source of insurance;2 however, it is unlikely that many of these women have access to abortion coverage or care through other sources. American Indians and Alaska Natives are almost twice as likely as the general population to have incomes below the poverty line19 and those who meet their state’s eligibility requirements may enroll in Medicaid or CHIP (whether or not they are also eligible for IHS services). Although these programs provide much-needed coverage, federal policy remains a barrier to abortion care through these programs in 35 states and DC. Moreover, for many Native Americans and Alaska Natives, and especially for those living in rural areas, IHS-supported programs are the only source of health care services available in the area.20 Thus, a woman who has abortion coverage or is able to come up with the money to pay for an abortion may still be unable to access care because of the restrictive IHS policy.

Peace Corps Volunteers

The Peace Corps provides and covers the cost of necessary health care for its nearly 7,000 volunteers.21,22 However, Congress imposed a total ban on abortion coverage for Peace Corps volunteers in 1978. This ban was modified in 2014 to include exceptions for life endangerment, rape and incest. More than half of all Peace Corps volunteers are women, most of whom are young (the average age of a volunteer is 28).22 Volunteers receive only modest monthly stipends meant to cover the cost of living and little more, and the vast majority serve in developing countries. For many female Peace Corps volunteers experiencing an unintended pregnancy, a safe abortion may be many thousands of miles and dollars away.

Federal Prisoners and Detainees

No women are more restricted in their health care choices than those detained in correctional or detention facilities. In 1986, Congress first prohibited the Department of Justice from providing abortion care for women in federal prisons, except in the limited cases of life endangerment or rape; the current policy also includes an exception for incest. Women held in immigration detention centers operated by ICE are likewise denied abortion care (except in the same limited circumstances) as a result of federal regulations. For a pregnant inmate or detainee who cannot access abortion services under one of the exceptions, the only recourse is to come up with the money to pay for care herself—a virtually impossible task for many of the 13,000 women serving time in federal prisons23 or for the thousands of women detained by ICE.24 Whether an abortion is covered under one of the exceptions or paid for directly by the woman, the Bureau of Prisons or ICE arranges for care at an outside facility.

Restrictions on Private Coverage

In the decades since Roe v. Wade, antiabortion legislators at the state level have also restricted insurance coverage to make abortion more difficult to obtain. Until recently, the most common action taken by states was to impose bans or near-bans on public employees’ insurance plans. But some states also took steps to restrict private insurance coverage of abortion more broadly, and 10 states currently have policies in place that restrict abortion coverage in all private plans written in the state.25

Efforts to restrict private abortion coverage intensified once Congress passed and President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. Under the ACA, states retain the option to restrict abortion coverage in the law’s health insurance marketplaces, and 25 states currently do so.25 At the same time, even where abortion coverage remains allowable under state law, insurance companies that sell private marketplace plans must comply with special accounting and disclosure rules under the ACA if they opt to include abortion coverage beyond the limited cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. These restrictions single out abortion and treat it differently from all other health care typically covered by private insurance policies, which perpetuates the stigma attached to abortion.

Furthermore, clear information on whether and to what extent marketplace plans cover abortion is often not readily available to consumers; a previous Guttmacher analysis suggested it can be difficult for a woman shopping for insurance to identify a plan that includes abortion coverage (see "Abortion Coverage Under the Affordable Care Act: Advancing Transparency, Ensuring Choice and Facilitating Access," Winter 2015). And even though the Obama administration took steps to advance transparency about abortion coverage in the marketplaces, transparency as a goal only goes so far if abortion coverage is not available in the first place. As of 2015, evidence suggests that there were only 18 states and the District of Columbia where even a single plan including abortion coverage was available on the marketplace.26

Looking Ahead

As President-elect Trump and members of the 115th Congress prepare to take office, reproductive health advocates and policymakers are readying for large-scale and numerous efforts to roll back rights and access, whether in broad form via the wholesale dismantling of the ACA and critical safety-net programs, or by more specific attacks on family planning programs and abortion care. With regard to abortion coverage, President-elect Trump has publicly pledged his commitment to making the Hyde Amendment permanent,27 and he has a ready antiabortion champion in Vice President-elect Pence.

To be sure, President Trump and Vice President Pence will be able to use their considerable administrative power to make it harder for women to access abortion coverage even in those cases currently permitted under federal law. But it will take an act of Congress to enshrine the Hyde Amendment or related restrictions in permanent law. Antiabortion policymakers—having maintained majorities in both chambers of Congress—are undoubtedly planning an aggressive assault on abortion rights. In recent years, social conservative lawmakers have routinely tried to incorporate Hyde Amendment language or references into new legislation, including bills that otherwise had little to do with reproductive health.28 As conservatives double down on this tactic and new policy disputes unfold, supporters of abortion rights will have their work cut out for them to stand strong against incursions that extend the harms of the Hyde Amendment to new populations.

Faced with these challenges, advocates and policymakers must not lose sight of the people who stand to be harmed the most by new restrictions on abortion access: low-income women, women of color and all those already affected by abortion coverage restrictions. Fortunately, we do not have to look far for a model when it comes to a better approach for our public policy on abortion coverage. In recent years, a new surge of momentum behind efforts to restore abortion coverage led to the introduction of federal legislation and a shift in the political narrative on this issue (see "Abortion in the Lives of Women Struggling Financially: Why Insurance Coverage Matters," 2016). Central to this narrative are the women and families affected by the Hyde Amendment.

With the introduction of the Equal Access to Abortion in Health Insurance (EACH Woman) Act in the 114th Congress, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) and her colleagues in the House presented a bold new vision for abortion coverage in which the federal government must ensure access through the major roles it plays as a public insurer, employer and provider of health care services. The bill would also prohibit government actors (whether federal, state or local) from banning or otherwise limiting abortion coverage in the private market. By the end of 2016, Rep. Lee was joined by 129 of her colleagues as cosponsors of the EACH Woman Act. Also in 2016, the Democratic Party platform called for the elimination of the Hyde Amendment for the first time in history, and as antiabortion pundits increasingly demanded that the Hyde Amendment be made permanent, the tenor and tone of their messaging took on a decidedly defensive note.

This momentum and, more importantly, the vision driving it have not lost their relevance in a changed political climate. To the contrary, they are more important than ever. As antiabortion policymakers double down on efforts to eliminate insurance coverage of abortion, they must be held accountable. All women should have access to abortion coverage, regardless of income, source of insurance or zip code. Policymakers who seek to deny this coverage must be required to make their case to the American people—no small task given that the majority of voters believe a woman should not be denied insurance coverage for abortion just because she is poor.29,30