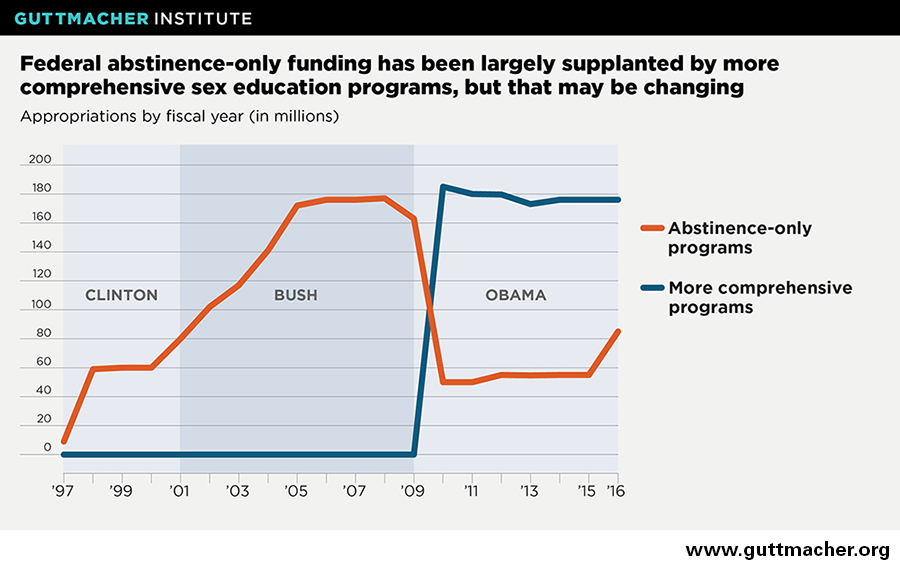

Over the past two decades, the United States has spent approximately $2 billion on ineffective and stigmatizing programming for adolescents focused on promoting abstinence from sex outside of marriage. Funding for these programs was reduced significantly while President Obama was in office, shifting in large part to support more comprehensive, medically accurate and age-appropriate programs. Now, with social conservatives in Congress emboldened by the 2016 elections and a new federal administration that includes proponents of abstinence-only-until-marriage programs, we are again at a crossroads when it comes to federal support for sex education. Although federal spending in this area represents just a fraction of the total amount invested annually by state and local governments, it has a significant impact on the development and implementation of sex education standards and curricula at all levels and sends an important message about our priorities as a nation.

Abstinence-only programs violate adolescents’ rights, ignore their needs and do not work. Adolescents have a basic human right to complete and accurate information about their sexual and reproductive health.1,2 The abstinence-only-until-marriage approach withholds comprehensive information on effective ways to reduce the risks of unintended pregnancy, HIV and other STIs, which violates adolescents’ right to information and also requires educators to disregard basic ethical standards by providing incomplete and potentially harmful information to students.3

Programs that seek to stop adolescents from having sex before marriage are also out of touch with the lives and needs of young people. Ninety-five percent of Americans have sex before marriage and, on average, adolescents in the United States have sex for the first time at about age 17 but do not marry or begin having children until their mid- to late 20s.4,5 During this long interim period, they may be at heightened risk for unintended pregnancy and STIs. Yet abstinence-only programs denigrate sexual activity before marriage as shameful and ignore the needs of sexually active adolescents. Such programs have also been found to reinforce gender stereotypes and exclude or stigmatize individuals on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.6–9

Given this reality, it is especially alarming that the federal government continues to spend money on programs that simply do not work. Although a small number of abstinence-only programs have shown limited effectiveness, the weight of scientific research indicates that strategies that solely promote abstinence outside of marriage while withholding information about contraceptives do not stop or even delay sex.10,11 To the contrary, abstinence-only programs can actually place young people at increased risk of pregnancy and STIs once they do become sexually active.12

Although federal abstinence-only-until-marriage funding has dropped since its peak at $177 million in fiscal year (FY) 2008, recent appropriations indicate it is on the rise once again (see chart). For FY 2016, Congress raised annual funding for abstinence-only programs from $55 million to $85 million. The bulk of this money—$75 million—is allocated for the Title V abstinence education program, a grant program for states that contains an eight-point statutory definition of an eligible "abstinence education" program. Among its points are teaching that "sexual activity outside of the context of marriage is likely to have harmful psychological and physical effects" and that "a mutually faithful monogamous relationship in the context of marriage is the expected standard of human sexual activity."13 The remaining $10 million is directed to a grant program for community-based organizations recently repackaged as "sexual risk avoidance" education, which seeks to teach adolescents how to "voluntarily refrain from non-marital sexual activity" and avoid "youth risk behaviors…without normalizing teen sexual activity."14

Federal policy should focus on comprehensive, medically accurate and age-appropriate programs. Strong evidence suggests that comprehensive approaches to sex education help young people to delay sex and also to have healthy, responsible and mutually protective relationships when they do become sexually active. Many examples of comprehensive programs have resulted in delayed sexual debut, reduced frequency of sex, fewer sexual partners, increased condom or contraceptive use, or reduced sexual risk-taking.15 More generally, population-based studies have found that reproductive health outcomes improve when adolescents receive formal sex education that includes information about contraception and abstinence.16,17 Accordingly, leading public health and medical professional organizations support a comprehensive approach to sex education—stressing the need for medically accurate, age-appropriate curricula that include information about both abstinence and contraception.18

Although there is no federal funding stream dedicated to promoting truly comprehensive sex education, federal funding for teen pregnancy prevention has largely shifted away from a focus on abstinence-only programs to a more comprehensive approach that educates adolescents about contraception in addition to abstinence. Of the $176 million provided for more comprehensive programs in FY 2016, $75 million went to the Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), a grant program that mainly provides funds to states for programs that educate adolescents about both abstinence and the use of contraception for the prevention of pregnancy and STIs. The other $101 million funded the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, a competitive grant program geared toward community-based groups to support evidence-based and innovative teen pregnancy prevention approaches. Recent evaluations of programs funded under this initiative showed that roughly one in three had successfully demonstrated a positive impact—a larger proportion than typically found in evaluation efforts of this nature and thus an impressive result.19,20

These federal initiatives are far from perfect. Their focus on reducing teen pregnancy without distinguishing between intended and unintended pregnancies reflects an assumption that young people should not become parents. Moreover, the primary goal of these policies is not to support adolescents to have healthy relationships and lead healthy lives; instead, they were designed to achieve specific outcomes: reducing the incidence of pregnancy, HIV and other STIs among young people. Nonetheless, these two funding streams place emphasis on scientific evidence, medical accuracy and information tailored to adolescents’ specific age and needs, and the programs they fund can implement elements of comprehensive sex education.

Fully supporting adolescents requires making these federal initiatives better.9 One vehicle for improvement is the Real Education for Healthy Youth Act (REHYA), sponsored in the 114th Congress by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), which sets out a holistic vision for comprehensive sexuality education nationally. REHYA would ensure federal funding for programs that provide adolescents and young adults with "the information and skills [they] need to make informed, responsible, and healthy decisions in order to become sexually healthy adults and have healthy relationships."21 These programs would address a range of topics, from anatomy and physiology to healthy relationships, dating violence, and gender roles and identity. They would also provide information about the importance of abstinence and contraceptive use for the prevention of unintended pregnancy, HIV and other STIs.

Programs that benefit adolescents are at risk. Members of Congress must soon turn their attention to the task of funding federal agencies and programs for the remainder of FY 2017 and all of FY 2018. Given current conservative pressures to drastically cut domestic spending and taxes across the board, and with a like-minded administration now in the White House, social conservatives will likely press forward with efforts to significantly reduce or eliminate funding for the more comprehensive programs that currently serve adolescents: the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program and PREP. In particular, Congress must reauthorize PREP for the program to survive beyond FY 2017. At the same time, Congress will have the opportunity to reauthorize the Title V abstinence-only program and to set new funding levels for it as well as the smaller grant program for "sexual risk avoidance" education. Despite the current emphasis on reducing spending levels, proponents of abstinence-only education may seek to ramp up funding in this area without affecting overall spending by diverting money from the more comprehensive programs.

Congress and the Trump administration are facing a significant choice: whether to promote ideology over the health and rights of young people, or direct federal investment toward more comprehensive programs in support of their sexual and reproductive health and well-being. Federally funded programs play a key role in guiding the standards and curricula developed and funded at the state and local levels—fundamentally shaping the definition and scope of sex education nationwide. At this critical juncture, how our country chooses to spend federal dollars will speak volumes about our priorities as a nation.