Efforts to change fundamental aspects of the Medicaid program have been central this year to congressional efforts to repeal and replace key components of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The most prominent attacks on Medicaid in the anti-ACA bills would involve massive cuts to the program’s federal financing. In addition, the bills would give states the authority to move Medicaid away from its current role as a public health insurance program designed to meet the long-term needs of low-income people, fundamentally changing its structure for the people who rely on it for health coverage. One proposed provision would allow states for the first time to institute work requirements for Medicaid enrollees. Another would give states the option to receive federal funding as a block grant, which would effectively eliminate a vast array of patient protections under current federal Medicaid law in states that take up this option.

Simultaneously, the Trump administration has been working to help states make changes to Medicaid by encouraging them to ask for research and demonstration "waivers" of federal law. In a letter to governors in March 2017, senior administration officials promised to fast-track waiver approvals—particularly those that "build on the human dignity that comes with training, employment and independence" and "help working age, nonpregnant, non-disabled adults prepare for private coverage."1 Conservative state policymakers have been pushing the limits of Medicaid waiver authority for years, but the Obama administration determined that much of what these policymakers want is simply not allowable under federal law, even via a waiver (see "How Might State Innovations in Health Reform Affect Sexual and Reproductive Health Care?," 2016).

Regardless of whether these types of changes happen via Congress, the Trump administration or both, they would have the distinct potential to undermine coverage and care. That is especially true for reproductive health services, as Medicaid is an indispensable source of coverage for these services (see "Why Protecting Medicaid Means Protecting Sexual and Reproductive Health," 2017). At the same time, cutting people off from family planning and other reproductive health care would undermine the purported goals of many of these proposed changes to Medicaid.

What Conservatives Want

One of the most prominent attempts to reshape Medicaid is to impose requirements for some Medicaid enrollees to have a job or participate in other approved activities to put them on the road to employment. Work requirements have been included in multiple anti-ACA bills this year and in several active waiver requests (none yet granted) from Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Utah and Wisconsin.2,3

Conservatives have also proposed to limit how long an individual can be enrolled in Medicaid or to lock out an enrollee from Medicaid for a period of time if she fails to follow specific Medicaid rules. Sometimes these proposals are explicitly paired with work requirements, by allowing individuals only a set number of months on Medicaid if they are not working or locking out enrollees for a time if they fail to maintain their work-related activities. Lock-out periods have been allowed in several Medicaid waivers for enrollees who fail to pay premiums, but lifetime limits—included in waiver requests by Arizona, Maine, Utah and Wisconsin—have not yet been approved.2,3

States have proposed several other paternalistic Medicaid requirements, such as the mandatory drug screening and testing for enrollees that was part of a 2017 Wisconsin waiver request.4 The state would require applicants to complete a screening questionnaire about current and prior use of controlled substances, submit to drug testing if indicated, and submit to substance abuse treatment if the test is positive—despite the fact that a single positive drug test may not indicate that an individual is addicted and requires treatment.

On a similar note, approved waivers in Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Montana, along with proposed waivers in several other states, include so-called healthy behavior incentives.2,3 These involve offers like reduced premiums or cost sharing for enrollees who make designated changes on issues such as alcohol consumption, tobacco use, weight loss, chronic disease management and seatbelt use. Kentucky’s waiver request goes so far as to pair a lock-out period (for failing to properly report changes to income, employment status and the like) with an incentive to take financial and health literacy classes.5 Those who agree to complete such a class would be allowed to re-enroll in Medicaid before the six-month lock-out period ends.

In addition, conservatives have been working to overhaul Medicaid’s strict limits on premiums and cost sharing for enrollees. Conservative policymakers would prefer to increase these payments, impose lock-out periods on enrollees who fail to pay, and apply them to a larger number of enrollees, including people with little or no annual income.2,3 These are only some of the numerous proposals from conservatives that target long-standing Medicaid protections designed to make it easier to participate in the program and use it to access affordable care.

Competing Visions for Medicaid

Many of these potential changes are rooted in a conservative vision of Medicaid as a welfare program that people should rely on only briefly during their lives. For example, work requirements would purportedly incentivize people to find jobs that would allow them to afford private coverage. Time limits would ensure that people do not become dependent on Medicaid coverage. Mandatory drug testing would supposedly get people into treatment and on the path to a more productive life—one that does not involve government assistance.

However, this vision of Medicaid would reverse decades of changes in Medicaid law that delinked it from government welfare programs and transformed it into an integral part of the U.S. health insurance system. Reproductive health has been at the center of this evolution: In the 1980s, Medicaid was expanded to cover pregnant women at income levels much higher than those set for traditional enrollees, such as families receiving cash welfare assistance. Later, Medicaid was expanded to allow states to cover family planning services for people otherwise ineligible for full-benefit Medicaid coverage, as well as individuals needing treatment for breast or cervical cancer.

The evolution of Medicaid culminated with the ACA, which firmly established Medicaid as a long-term solution for health coverage for low-income people of all ages, regardless of family structure. Medicaid (along with its companion program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program) now covers about 74 million people, making it the nation’s largest health insurance program.6 It is central to reproductive health, covering 20% of U.S. women of reproductive age, paying for half of all U.S. births and accounting for 75% of public dollars spent on family planning.7–9

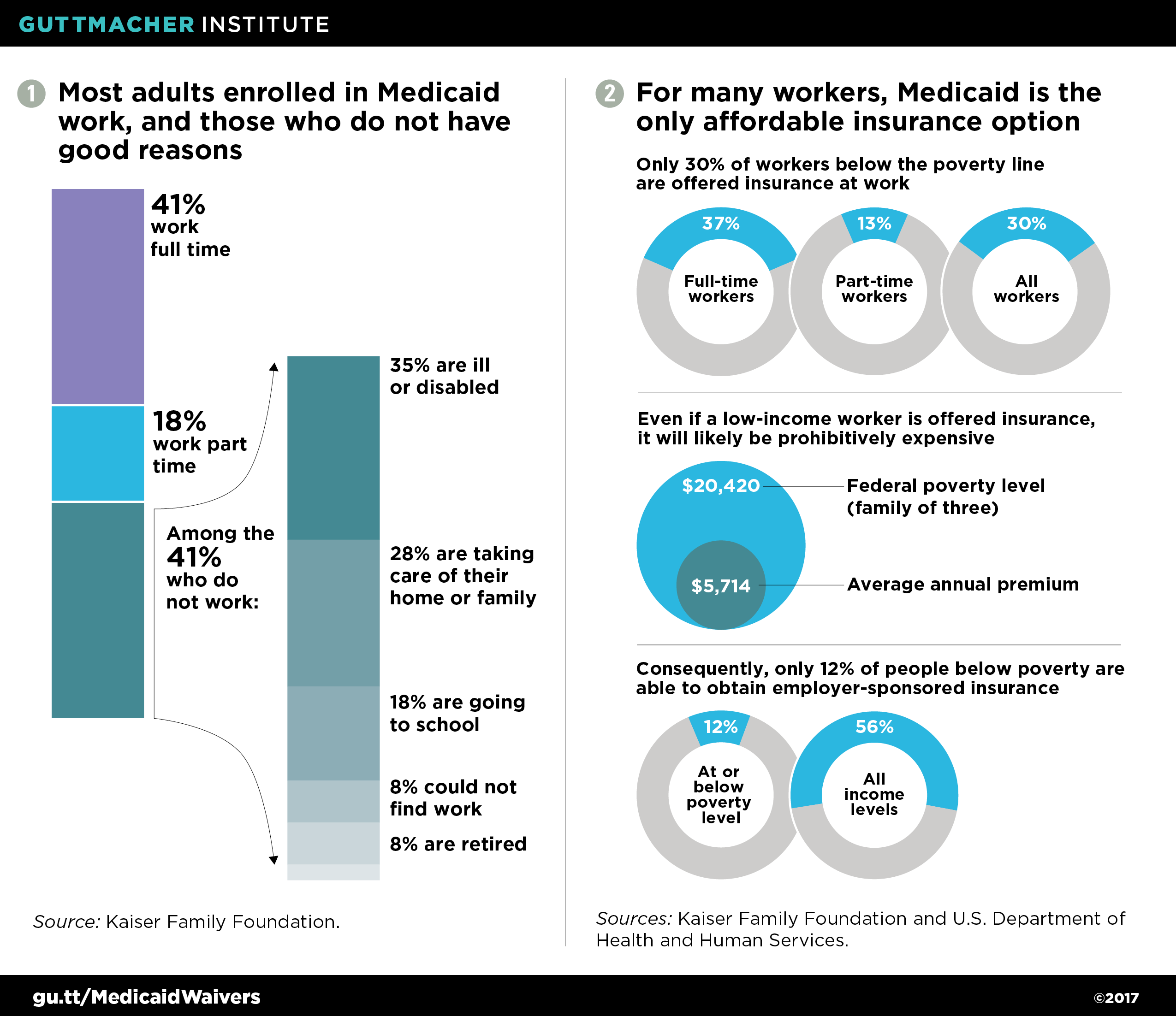

Medicaid’s expansive role addresses the fact that low-paying jobs often do not lead to private insurance coverage: many employers do not offer it, many employees do not qualify if it is offered, and many of those who qualify cannot afford the premiums and deductibles.10 And many millions of Americans will never secure higher paying jobs with better benefits, because economic mobility remains limited in this country.11 In reality, Medicaid may be the only affordable option for many people at multiple times in their life, or for decades at a time. And contrary to the stereotypes that conservatives often promulgate, most adults on Medicaid who are able to work do work, and those who are not working have good reasons: having an illness or disability, taking care of their home and family, going to school, being unable to find a job or being already retired from the workforce (see figures 1 and 2).12–15

A related conservative vision for Medicaid is to transform the program so it looks more like private insurance. Under this vision, Medicaid enrollees should pay premiums and copayments and be locked out of Medicaid if they fail to pay. This would supposedly serve as a form of training, so that enrollees understand what will be expected of them financially if and when they enroll in a private insurance plan. And cost sharing would supposedly incentivize Medicaid enrollees to avoid unnecessary care—requiring what conservatives call "skin in the game," even for disadvantaged people with little financial skin to spare.

This vision conflicts with long-established Medicaid policies that are based on the idea that insurance for low-income people must be designed to meet their needs and circumstances. Decades of research have made it clear that premiums can dissuade low-income people from enrolling and staying enrolled in coverage, and that cost sharing can dissuade them from seeking needed care.16,17 It is for the latter reason that Medicaid has long exempted family planning services, among other critical services, from all forms of cost sharing. Not only has Congress repeatedly reaffirmed these protections, but it has applied some of them to private insurance, such as through the ACA’s requirement that most private plans cover dozens of preventive services, including contraception, without cost sharing.

Undermining Reproductive Health

Advocates for Medicaid enrollees have cited a host of legal, practical, clinical and ethical arguments against conservative proposals for Medicaid.3,18,19 These proposed changes would have a particularly harmful effect on Medicaid enrollees’ access to the reproductive health care they need. Work requirements, time limits, lock-out periods, mandatory drug testing, expanded use of premiums and other proposals would constitute barriers to getting and staying enrolled in Medicaid. Expanded cost sharing would be a barrier to using that coverage for family planning services, maternity care, STI testing and treatment and more. All of these requirements would interfere with continuity of care, undermine patient-provider relationships and jeopardize patient health.20,21

One reason these barriers are particularly problematic for reproductive health care is that these services often address long-term needs, rather than acute, one-time needs. The typical U.S. woman will spend about three years pregnant, postpartum or attempting to become pregnant and about three decades trying to avoid pregnancy and therefore in need of contraceptive care.22 Similarly, people may be at risk of acquiring HIV or other STIs as long as they are sexually active, and continue to be at risk of developing cervical cancer and other reproductive health–related cancers for decades afterwards.

Conservatives’ vision for Medicaid could also be potentially coercive when it comes to reproductive health. For example, time limits, lock-out periods, premiums and cost sharing might provide strong financial incentives for Medicaid enrollees to choose long-term or permanent contraceptive methods, either out of concern that they may only have insurance coverage for a short time or in order to avoid paying further premiums or copayments. Healthy behavior incentives—if designed around unintended pregnancy, STIs and other negative reproductive health outcomes—could be used coercively to promote long-term contraceptives or to promote abstinence outside of marriage. The United States has a long history of paternalism and coercion when it comes to reproductive health, particularly for low-income people and people of color.23

In practice, implementing the conservative vision for Medicaid—and interfering with family planning care specifically—would be counterproductive to the social and economic goals that conservatives say they are pursuing. A majority of women report that family planning has helped them to complete their education, get and keep a job, and take care of themselves and their families, and decades of research back up these positive outcomes.24 Affordable health care more generally allows people to achieve these goals by helping them address chronic and acute health issues that can interfere with their ability to work, study or care for others.

One illustrative example is a 2017 waiver proposal from Maine, which would impose work requirements, time limits and premiums on the state’s Medicaid family planning expansion and on full-benefit coverage, including family planning, for many adult Medicaid enrollees.25 The waiver went through public hearings and a state-level comment period in the spring and was submitted for federal approval in August; as of the end of September, it is still under consideration and the Trump administration is widely expected to approve some or all of the state’s requests. The state’s waiver application summarized public comments pointing out how counterproductive and harmful it would be to apply work requirements and time limits to the family planning services people rely on to help them get and keep a job, but the state declined to make any changes in response to those arguments.

Maine’s proposed premiums, as applied to the family planning expansion, would be especially ridiculous: Enrollees would be charged as much as $30 per month, or $360 a year, to enroll in a plan exclusively for family planning services. That amount is well above the average annual cost of providing publicly supported family planning care26 or what an uninsured person might pay out of pocket for many forms of contraception. It is difficult to predict what the impact of such a premium could be, but none of the scenarios are positive ones. Most likely, enrollment in the family planning expansion would plummet. Some people might decide to instead pay out of pocket at a pharmacy, greatly limiting their choice of contraceptive methods and denying them other preventive care that can be obtained during a family planning visit. Or they could rely on free or subsidized care at safety-net family planning providers; that would be paid for by scarce grant funding rather than Medicaid reimbursement, thereby making it harder for providers to serve all people in need. These premiums could also coercively lead some people to enroll in the Medicaid family planning expansion for just a single month in order to receive an IUD or contraceptive implant, even if they would prefer another option.

Misguided Proposals

Beyond a doubt, Medicaid can help people meet the same goals that conservative policy proposals attempt to achieve. Having Medicaid coverage can help people complete their education, obtain a better job, become more financially secure and achieve better health outcomes. Reproductive health care is a big part of this, and it has been for decades.

Medicaid and reproductive health care contribute to all of these goals by giving people the tools they need to make their own decisions in consultation with health care providers who are obligated to put their patients’ interests first. By contrast, conservative proposals to reshape Medicaid use threats and punishment to try to force people to make what some policymakers think are better decisions. Coercion of that sort is a violation of reproductive rights and human rights more broadly. And it is likely to backfire by denying people the coverage, care, dignity and autonomy that they need to protect and improve their health and well-being.