Abstract

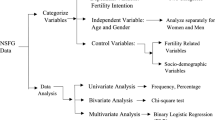

While recently there have been renewed interest in women’s childbearing intentions, the authors sought to bring needed research attention to understanding men’s childbearing intentions. Nationally representative data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) was used to examine pregnancy intentions and happiness for all births reported by men in the 5 years preceding the interview. We used bivariate statistical tests of associations between intention status, happiness about the pregnancy, and fathers’ demographic characteristics, including joint race/ethnicity and union status subgroups. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios of a birth being intended, estimated separately by father’s union status at birth. Using comparable data and measures from the male and female NSFG surveys, we tested for gender differences intentions and happiness, and examined the sensitivity of our results to potential underreporting of births by men. Nearly four out of ten of births to men were reported as unintended, with significant variation by men’s demographic traits. Non-marital childbearing was more likely to be intended among Hispanic and black men. Sixty-two percent of births received a 10 on the happiness scale. Happiness about the pregnancy varied significantly by intention status. Men were significantly happier than women about the pregnancies, with no significant difference in intention status. Potential underreporting of births by men had little impact on these patterns. This study brings needed focus to men’s childbearing intentions and improves our understanding of the context of their role as fathers. Men need to be included in strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These men were asked “When did you find out that (partner) was pregnant? Was it during the pregnancy or after the child was born?”.

References

Finer, L. B., & Zolna, M. R. (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception, 84(5), 478–485.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 topics and objectives (2010). http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=13. Washington, D.C., US Government Printing Office. 8-30-2011.

Klerman, L. V. (2000). The intendedness of pregnancy: A concept in transition. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(3), 155–162.

Santelli, J. S., Lindberg, L. D., Orr, M. G., Finer, L. B., & Speizer, I. (2009). Toward a multidimensional measure of pregnancy intentions: Evidence from the United States. Studies in Family Planning, 40(2), 87–100.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). (1998). Nurturing fatherhood: improving data and research on male fertility, family formation, and fatherhood. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatrica, 97, 153–158.

Korenman, S., Kaestner, R., & Joyce, T. (2002). Consequences for infants of parental disagreement in pregnancy intention. Perspective Sex Reproduction Health, 34(4), 198–205.

Williams, L., Abma, J. C., & Piccinino, L. (1999). The correspondence between intention to avoid childbearing and subsequent fertility: A prospective analysis. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(5), 220–227.

Leathers, S. J., & Kelley, M. A. (2000). Unintended pregnancy and depressive symptoms among first-time mothers and fathers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(4), 523–531.

Waller, M. R., & Bitler, M. P. (2008). The link between couples’ pregnancy intentions and behavior: Does it matter who is asked? Perspective Sex Reproduction Health, 40(4), 194–201.

Bronte-Tinkew, J., Ryan, S., Carrano, J., & Moore, K. A. (2007). Resident fathers pregnancy intentions, prenatal behaviors and links to involvement with infants. Journal Marriage Family, 69, 977–990.

Bronte-Tinkew, J., Scott, M., & Horowitz, A. (2009). Male pregnancy intendedness and childrens mental proficiency and attachment security during toddlerhood. Journal Marriage Family, 71, 1001–1025.

Campbell, A. A., & Mosher, W. D. (2000). A history of the measurement of unintended pregnancies and births. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(3), 163–169.

Martinez, G.M., et.al. (2006). Fertility, contraception, and fatherhood: Data on men and women from Cycle 6 2002 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Report No.: 26 National Center for Health Statistics.

Abma, J. C., Chandra, A., Mosher, L., & Piccinino, L. (1997). Fertility, family planning, and women’s health: new data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Statistic, 23(19), 1–114.

Fischer, R. C., Stanford, J. B., Jameson, P., & DeWitt, M. J. (1999). Exploring the concepts of intended, planned, and wanted pregnancy. Journal of Family Practice, 48(2), 117–122.

Moos, M. K., Petersen, R., Meadows, K., Melvin, C. L., & Spitz, A. M. (1997). Pregnant women’s perspectives on intendedness of pregnancy. Womens Health Issues, 7(6), 385–392.

Stanford, J. B., Hobbs, R., Jameson, P., DeWitt, M. J., & Fischer, R. C. (2000). Defining dimensions of pregnancy intendedness. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(3), 183–189.

Miller, W. B. (1994). Reproductive decisions: How we make them and how they make us. Advances in Population: Psychosocial Perspectives, 2, 1.

Hartnet, C. (2012). Are Hispanic women happier about unintended births? Population Research and Policy Review, 31(5), 683–701.

Ventura, S. J. (2009). Changing patterns of nonmarital childbearing in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, 18, 1–7.

Furstenberg, F. (2009). If Moynihan had only known: Race, class, and family change in the late twentieth century. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621, 94–110.

Joyner, K., Peters, H., Hynes, K., Sikora, A., Rubenstein, J., & Rendall, M. (2012). The quality of male fertility data in major U.S. surveys. Demography, 49(1), 101–124.

Lepkowski, J. M., Mosher, W. D., Davis, K. E., Groves, R. M., & Van, H. J. (2010). The 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth: sample design and analysis of a continuous survey. Vital Health Statistic, 2(150), 1–36.

Jones, R. K., & Kost, K. (2007). Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States: an analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Studies in Family Planning, 38(3), 187–197.

Mosher, W.D., Jones, J., Abma, J.C. (2012). Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982–2010. Report No.: 55. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD.

Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version Release 12. College Statio, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Smock, P., & Greenland, F. (2010). Diversity in pathways to parenthood: patterns, implications, and emerging research directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 576–593.

Zolna, M. R., & Lindberg, L. D. (2012). Unintended pregnancy: Incidence and outcomes among young adult unmarried women in the United States, 2001 and 2008. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Manning, W., & Landale, N. (1996). Racial and ethnic differences in the role of cohabitation in premarital childbearing. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(1), 63–77.

Johnson, T., O’Rourke, D., Chavez, N., Sudman, S., Warnecke, R., & Lacey, L. (1997). Survey cognition and response to surveys questions among culturally diverse populations. In L. Lyberg, P. Biemer, M. Collins, E. D. De Leeuw, & C. Dippo (Eds.), Survey Measurement and Process Quality (pp. 87–114). New York: Wiley.

Stewart, A. L., & Napoles-Springer, A. M. (2003). Advancing health disparities research: can we afford to ignore measurement issues? Medical Care, 41(11), 1207–1220.

Bachrach, C., & Sonenstein, F. (1998). Male fertility and family formation: Research and data needs on the pathways to fatherhood. In Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family statistics (Ed.), Nurturing fatherhood: Improving data and research on male fertility, family formation and fatherhood (pp. 45–98). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Office of Family Planning,Department of Health and Human Services.(2007) Title X male involvement prevention services.

Chabot, M., Lewis, C., de Bocanegra, H., & Darney, P. (2011). Correlates of receiving reproductive health care services among US men aged 15–44 years. America Journal Mens Health, 5(4), 358–366.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by award R01HD068433 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindberg, L.D., Kost, K. Exploring U.S. Men’s Birth Intentions. Matern Child Health J 18, 625–633 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1286-x

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1286-x