Abstract

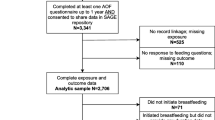

Better understanding of the impact of unintended childbearing on infant and early childhood health is needed for public health practice and policy. Data from the 2004–2008 Oklahoma Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System survey and The Oklahoma Toddler Survey 2006–2010 were used to examine associations between a four category measure of pregnancy intentions (intended, mistimed <2 years, mistimed ≥2 years, unwanted) and maternal behaviors and child health outcomes up to age two. Propensity score methods were used to control for confounding. Births mistimed by two or more years (OR .58) and unwanted births (OR .33) had significantly lower odds than intended births of having a mother who recognized the pregnancy within the first 8 weeks; they were also about half as likely as intended births to receive early prenatal care, and had significantly higher likelihoods of exposure to cigarette smoke during pregnancy. Breastfeeding was significantly less likely among unwanted births (OR .68); breastfeeding for at least 6 months was significantly less likely among seriously mistimed births (OR .70). We find little association between intention status and early childhood measures. Measured associations of intention status on health behaviors and outcomes were most evident in the prenatal period, limited in the immediate prenatal period, and mostly insignificant by age two. In addition, most of the negative associations between intention status and health outcomes were concentrated among women with births mistimed by two or more years or unwanted births. Surveys should incorporate questions on the extent of mistiming when measuring pregnancy intentions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Oklahoma is one of only four states with data available from follow-up interviews of PRAMS mothers; the others are Alaska, Rhode Island, and Oregon.

Only one other state (Utah) included such a question in the PRAMS survey during the same period.

Response categories were less than 1 year, 1 year to less than 2 years, 2 years to less than 3 years, 3 years to less than 4 years, 4 years or more.

Mothers slightly overestimate early entry into prenatal care on the PRAMS survey (Oklahoma State Department of Health, PRAMSGRAM Initiation of Prenatal Care Among Women Having a Live Birth in Oklahoma, 1995, 5(2) http://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/PRAMS_Initiation%20of%20PNC_95.pdf.pdf, accessed 11/21/13); however, these small overestimates are unlikely to affect our final estimates substantially.

This measure was drawn from the linked birth certificate.

Defined as diarrhea lasting at least 3 days, an ear infection, or a cold or runny nose with a fever or cough.

Paired comparisons of differences in the size of the proportions for intention status groups for individual attributes were tested for statistical significance using t tests. Only statistically significant differences are mentioned in the text (p < .05).

References

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Clinical preventive services for women: Closing the gaps. Report of the Committee on Preventive Services for Women. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences Press.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Healthy People 2020 topics & objectives. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicid=13

Gipson, J. D., Koenig, M. A., & Hindin, M. J. (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39(1), 18–38.

Logan, C., Holcombe, E., Manlove, J., & Ryan, S. (2007). The consequences of unintended childbearing: A white paper. Washington, DC: Child Trends and The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

Joyce, T. J., Kaestner, R., & Korenman, S. (2000). The effect of pregnancy intention on child development. Demography, 37(1), 83–94.

Baydar, N. (1995). Consequences for children of their birth planning status. Family Planning Perspectives, 27(6), 228–34, 245.

Crissey, S. R. (2005). Effect of pregnancy intention on child well-being and development: Combining retrospective reports of attitude and contraceptive use. Population Research and Policy Review, 24(6), 593–615.

Carson, C., et al. (2011). Effect of pregnancy planning and fertility treatment on cognitive outcomes in children at ages 3 and 5: Longitudinal cohort study. British Medical Journal, 343, d4473.

Hummer, R. A., Hack, K. A., & Raley, R. K. (2004). Retrospective reports of pregnancy wantedness and child well-being in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 25(3), 404–428.

Finer, L. B., & Zolna, M. R. (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception, 84(5), 478–485.

Rosenberg, K. D., et al. (2011). New options for child health surveillance by state health departments. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(3), 302–309.

Santelli, J., et al. (2003). The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 94–101.

Klerman, L. V. (2000). The intendedness of pregnancy: A concept in transition. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(3), 155–162.

Pulley, L., Klerman, L. V., Tang, H., & Baker, B. A. (2002). The extent of pregnancy mistiming and its association with maternal characteristics and behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(4), 206–211.

Mosher, W. D., Jones, J., & Abma, J. C. (2012). Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center of Health Statistics.

Lindberg, L. D., Finer, L. B., & Stokes-Prindle, C. (2008). Refining measures of pregnancy intention: Taking timing into account. In 2008 Annual meetings of the Population Association of America. New Orleans, LA.

Oklahoma State Department of Health. (2006). PRAMSGRAM: Unintended pregnancy. http://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/PRAMS_Unintended_Pregnancy_06.pdf.pdf

Oklahoma State Department of Health. (2010). TOTS brief: The Oklahoma Toddler Survey. http://www.ok.gov/health2/documents/Imm_Brief_final_Dec_2010.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). PRAMS model surveillance protocol, 2009 CATI version. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/PDF/ProtocolFiles/ProtocolZipFile.zip

Oklahoma State Department of Health. (2012). TOTS 2012 protocol. Unpublished manuscript available upon request at TOTS@health.ok.gov.

Singh, G., Siahpush, M., & Kogan, M. D. (2010). Disparities in children’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the United States, 2007. Pediatrics, 126(5), 1052.

Hagan, J. F., Shaw, J. S., & Duncan, P. M. (Eds.). (2008). Bright futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

Austin, P. C. (2011). An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(3), 399–424.

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science, 25(1), 1–21.

Imbens, G. W. (2000). The role of the propensity score in estimating dose–response functions. Biometrika, 87(3), 706–710.

Guo, S., & Fraser, M. W. (2010). Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lunceford, J. K., & Davidian, M. (2004). Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: A comparative study. Statistics in Medicine, 23(19), 2937–2960.

Dugoff, E. H., Schuler, M., & Stuart, E. A. (2013). Generalizing observational study results: Applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Services Research, 49(1), 284–303.

Sonfield, A., & Kost, K. (2013). Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: Estimates for 2008. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

Hayford, S. R., & Guzzo, K. B. (2010). Age, relationship status, and the planning status of births. Demographic Research, 23(13), 365–398.

D’Angelo, D. V., et al. (2004). Differences between mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among women who have live births. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(5), 192–197.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Gynecologic Practice & Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. (2009). Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 114(6), 1434–1438.

Speidel, J. J., Harper, C. C., & Shields, W. C. (2008). The potential of long-acting reversible contraception to decrease unintended pregnancy. Contraception, 78(3), 197–200.

Baldwin, M. K., Rodriguez, M. I., & Edelman, A. B. (2012). Lack of insurance and parity influence choice between long-acting reversible contraception and sterilization in women postpregnancy. Contraception, 86(1), 42–47.

Braveman, P., & Barclay, C. (2009). Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course perspective. Pediatrics, 124(Suppl 3), S163–S175.

Shah, P. S., et al. (2011). Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 205–216.

Durousseau, S., & Chavez, G. F. (2003). Associations of intrauterine growth restriction among term infants and maternal pregnancy intendedness, initial happiness about being pregnant, and sense of control. Pediatrics, 111(5 Part 2), 1171–1175.

Kost, K., Landry, D. L., & Darroch, J. E. (1998). The effects of pregnancy planning status on birth outcomes and infant care. Family Planning Perspectives, 30(5), 223–230.

McCrory, C., & McNally, S. (2013). The effect of pregnancy intention on maternal prenatal behaviours and parent and child health: Results of an Irish cohort study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 27(2), 208–215.

Guzzo, K. B., & Hayford, S. R. (2014). Revisiting retrospective reporting of first-birth intendedness. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-014-1462-7.

Joyce, T., Kaestner, R., & Korenman, S. (2000). The stability of pregnancy intentions and pregnancy-related maternal behaviors. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(3), 171–178.

Lewis, C. C., Pantell, R. H., & Kieckhefer, G. M. (1989). Assessment of children’s health status: Field test of new approaches. Medical Care, 27(Suppl. 3), S54–S65.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant R40 MC 25692 from the Maternal and Child Health Research Program, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD068433. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindberg, L., Maddow-Zimet, I., Kost, K. et al. Pregnancy Intentions and Maternal and Child Health: An Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Oklahoma. Matern Child Health J 19, 1087–1096 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1609-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1609-6