In October 2017, the first case of the Trump administration attempting to forcibly prevent an unaccompanied immigrant minor in federal custody from obtaining an abortion made headlines around the United States. At the center of these actions is the Office of Refugee Resettlement within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which is led by an ardent abortion-rights opponent. Lawsuits and media reports have revealed that officials are using a variety of tactics to pressure young women not to have the abortion they requested, including physically barring individuals in the government’s care from accessing the procedure. One attorney, speaking of her client, said that officials "literally held her hostage"1 to force her to continue the pregnancy.

The blatant coercion in these cases is shocking in its own right. But the ruthless way in which the Trump administration is attempting to impose its antiabortion ideology on these young women also serves as a vivid reminder that coercive intent and practices are at the very heart of social conservatives’ reproductive health agenda. During the 2016 election, Donald Trump enjoyed strong support from social conservatives.2 They see the Trump administration, combined with conservative control of both the U.S. House and Senate, as a "turning point" for their agenda.3

Divergent Values

Social conservatives hold prescriptive views—rooted in both religious doctrine and political ideology—on sexuality and reproductive decision making. Generally speaking, this worldview holds, and seeks to establish as norms for society at large, that people, especially adolescents, must abstain from sexual activity outside of marriage; women’s access to contraception should be limited to certain circumstances, primarily marriage, or that contraceptive options other than fertility awareness methods are unacceptable; women should welcome all pregnancies, including those resulting from rape; and, consequently, abortion should be severely restricted or banned entirely.

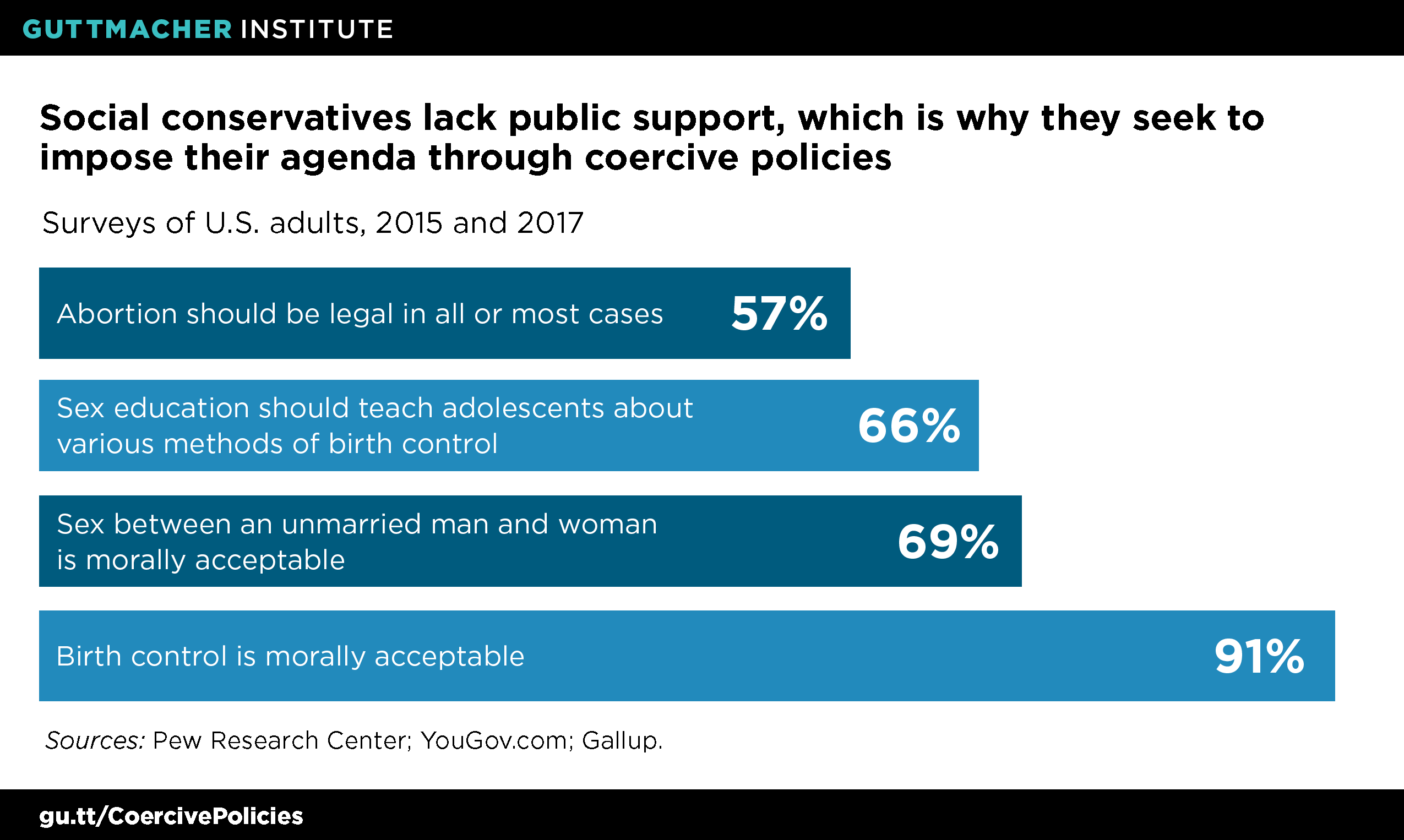

However, many Americans either disagree with these norms or otherwise do not conform to them (see figure).4–6 A 2017 Gallup report finds that "Americans hold record liberal views on most moral issues" and out of 19 morality questions polled, "no issues show meaningful change toward more traditionally conservative positions."4 This broad trend includes reproductive health and rights. Virtually every woman of reproductive age who has ever had sexual intercourse has used contraception.7 Likewise, public views on the legality of abortion have essentially held steady since the mid-1990s6 and abortion remains common.8 Premarital sex is the overwhelming norm in society as a whole9 and sex is common among young people as well; by age 18, well over half of female and male adolescents have had sexual intercourse.10 And a majority of Americans agree that sex education in schools should not focus exclusively on abstinence.

Many Forms of Coercion

Unable to sway the country’s moral compass or convince the public to make different reproductive health decisions by their own free will, social conservatives have long turned to using restrictions and prohibitions. A prime example is the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits women enrolled in Medicaid from using their insurance to pay for abortion care, with few exceptions. The Hyde Amendment exemplifies both social conservatives’ intent to coerce women’s decision making as well as their cynical opportunism in targeting vulnerable women in particular. Its congressional sponsor, the late Rep. Henry Hyde, admitted as much when he stated in 1977 that "I certainly would like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle-class woman, or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the…Medicaid bill."11

Coercive policies have also reigned supreme in the states, which enacted close to 1,200 abortion restrictions between 1973 and 2017, one-third of them in the last seven years alone.12 With unified control of the federal government since early 2017, social conservatives have attempted to replicate their state-level success at the federal level. Almost every reproductive health–related initiative from the Trump administration and social conservatives in Congress has fallen along a spectrum of coercion, using all available legislative, regulatory and administrative levers. Prominent examples include:

Imposing harmful funding restrictions on health care providers overseas. In January 2017, President Trump issued an executive order that reimposed and expanded the global gag rule to block U.S. global health funding for all foreign nongovernmental organizations that use their own funding to engage in abortion-related services or advocacy. This action impacts a vast global health portfolio in about 60 low- and middle-income countries, including programs on family planning, HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, malaria and nutrition.13 U.S. global health assistance aims to help the poorest people in particular, so the global gag rule is likely to hit the most vulnerable populations hardest.

The global gag rule is coercive on multiple levels. At its core, it seeks to deny women access to abortion-related information, counseling and services, thereby attempting to steer their decision making in a direction that aligns with the administration’s antiabortion ideology. The policy also coerces providers that accept U.S. funding. It forces them to violate medical ethics by withholding information from patients in their care.14 Further, it suppresses the speech and political participation of non-U.S. actors in their own countries in coercive and hypocritical ways: It handcuffs organizations and advocates that would otherwise use their own funds to lobby their own government to liberalize abortion laws, without imposing similar restrictions on those advocating to further restrict abortion.13

Blocking women from seeing the provider of their choice. Social conservatives have long sought to exclude Planned Parenthood from public programs and funding streams on ideological grounds, a campaign that kicked into overdrive both in the states and in Congress with the 2015 release of deceptively edited videos attacking the organization.15,16 At the congressional level, attempts to exclude Planned Parenthood health centers from receiving Medicaid reimbursement came close to succeeding last summer as part of broader efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

On this issue, too, the intent and the mechanism by which to achieve it are overtly coercive. Planned Parenthood health centers receive Medicaid reimbursement for contraceptive services, STI testing and treatment, cancer screenings and other care they provide to people enrolled in the program. There is no Medicaid funding dedicated to Planned Parenthood that could be "redirected," as socially conservative policymakers and their allies often assert. Rather, their goal is to prohibit people enrolled in Medicaid from going to Planned Parenthood as their provider of choice, regardless of whether alternative sources of care are available.17 These attacks ignore the fact that women choose to obtain family planning services from Planned Parenthood health centers because of the high-quality services they receive there.18 Moreover, by targeting Medicaid enrollees, these attacks are once again squarely aimed at the most disadvantaged women, including low-income women and women of color.

Making adolescents conform to harmful, one-size-fits-all norms. A core tenet for many social conservatives is the belief that refraining from sex outside of marriage is the only acceptable behavior for people of all ages, and certainly for adolescents. Consequently, they have long championed federal funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs. Their allies in Congress and the Trump administration are now moving aggressively to reshape policy accordingly, including by canceling evidence-based adolescent pregnancy prevention efforts in July 2017 and trying to rebrand discredited abstinence-only programs.19

Coercion is inherent in abstinence-only programs, because they routinely seek to pressure young people’s decision making by providing medically inaccurate and incomplete sexual health information and by perpetuating stigma around sex, sexual health and sexuality.20 Withholding information—for instance, on the benefits of contraceptive use—violates medical ethics, which is why leading medical organizations have taken strong stances against abstinence-only programs.20,21 Pushing abstinence until marriage as the exclusive message also undermines support for sexually active adolescents and those who are already pregnant or parenting. In addition, these programs often promote harmful gender stereotypes and systematically ignore the needs of marginalized groups, including LGBTQ young people. This, too, runs counter to medical ethics and personal autonomy.

Banning some reproductive health services outright. In October 2017, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would impose a federal ban on abortion at or after 20 weeks postfertilization (equivalent to 22 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period, or LMP). The Senate failed to advance the same legislation in January 2018, yet antiabortion lawmakers are committed to keep trying. Seventeen states already have similar laws on the books.22 Although the vast majority of abortions take place early in pregnancy, slightly more than 1% of them are performed at 21 weeks’ LMP or later.23

The intent behind the 20-week ban is obviously coercive, since it would block women who need an abortion from obtaining one and force them to carry their pregnancy to term. Further, such a ban would likely fall hardest on low-income women and women of color, who bear a disproportionate burden of unintended pregnancies.24 Women who obtain an abortion at or after 20 weeks’ LMP are also much more likely than those who obtain an abortion in the first trimester to report delays before they could get the procedure, because they had difficulty raising funds for the abortion and travel costs, or because they had difficulty securing insurance coverage.25

Other bans based on gestational age are just as coercive, but would ensnare a much larger number of abortion patients. In November 2017, a House committee held a hearing on a bill that would ban abortion as soon as a fetal heartbeat can be detected—as early as six weeks’ LMP. The bill would ban abortion before many women even know they are pregnant, entirely withholding the option to obtain a legal abortion.

Enabling coercion by third parties. In October 2017, the Trump administration released new federal regulations governing the ACA’s contraceptive coverage guarantee, which requires insurance plans to cover 18 contraceptive methods without copayments or deductibles, thereby empowering women to choose from the full range of birth control options. The administration’s move creates sweeping new exemptions for employers, universities, individuals and insurers with religious or moral objections to some or all contraceptive methods and services.26 As of early February 2018, the new regulations had been temporarily enjoined by two federal courts.

Restricting full contraceptive method choice in this way is inherently coercive. The new regulations open the door for employers and others to impose their religious or moral beliefs on employees, students and dependents by dictating whether and which contraceptive services are covered in their health insurance plans. This may interfere with women’s ability to afford and choose the contraceptive methods that work best for them, and women may instead be forced to rely on less expensive but, for them, less suitable options.27 The Trump administration’s birth control regulations build on long-standing efforts by social conservatives to misuse federal and state laws intended to protect religious freedom to instead impede access to reproductive health services.28

Growing Divide

None of this is new, of course. Across the globe, governments and other entities have long used coercion to undermine people’s reproductive autonomy, whether to compel women toward childbirth or to prevent certain groups of people from having children.29 The United States has a troubling and well-documented history of coercive policies and practices around reproductive health, particularly for low-income women, women of color and disabled women.30 Coercive practices were widely condoned during the early and mid-20th century, including forced sterilization of women deemed "unfit" to bear children.29

Women of color–led reproductive justice organizations in particular have been instrumental in pointing out systemic racism, oppression, implicit biases and other injustices in reproductive health policies, both at the global level and within the United States.29 These groups provide essential moral leadership and remain acutely sensitive to the potential for coercion. They are at the forefront of fighting against restrictive or otherwise coercive policies, as well as the shame and stigma that are often directed at women of color’s reproductive health decision making. Reproductive justice groups also were among the first to raise concerns that the growing popularity of highly effective methods like the IUD could lead policymakers and providers to steer women—especially young women, low-income women and women of color—toward these methods.30,31 Along the same lines, reproductive justice groups have sounded the alarm against offering incentives or imposing quotas that can distort the informed consent process or result in women being pressured into using one form of contraception over another.

Social conservatives have chosen a very different path. They are willfully disregarding the lessons of the past and doubling down on the idea that people cannot be trusted to make their own reproductive health decisions. The recent actions by the Office of Refugee Resettlement illustrate that social conservatives will readily cast aside basic human rights and individual autonomy to impose their agenda. And it is women like those young refugees—people who are the most vulnerable and therefore most susceptible to coercion—who bear the brunt of these attacks. All of this leaves little doubt that, given the opportunity, social conservatives would readily impose their will on all of U.S. society in the same manner.