The past year has seen wild swings in sexual and reproductive health and rights policy. In June 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a Texas law that imposed crippling and unnecessary regulations on abortion providers, which was passed under the pretext of protecting women’s health and safety. In its ruling, the Court admonished the federal appeals court for deferring to the Texas legislature’s stated intentions instead of examining the extensive and compelling factual record, which showed that the restrictions did nothing to protect women’s health and demonstrably impeded their access to care. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg underscored that point in her concurrence, saying that laws like the one in Texas "that ‘do little or nothing for health, but rather strew impediments to abortion’…cannot survive judicial inspection."1 In other words, sound data and evidence win.

But within months, the nation was confronted with a new administration expounding what one key spokesperson infamously described as "alternative facts."2 Indeed, the Trump administration—which includes a health policy advisor on the President’s Domestic Policy Council who contends that contraception impairs future fertility3—has many observers deeply concerned that we are entering a fact-free era when it comes to setting policy around sexual and reproductive health and rights.

In reality, however, much of the antiabortion universe has long been an evidence-free zone, as many of the movement’s signature initiatives and proposals are devoid of any factual foundation. In fact, at least 10 major categories of abortion restrictions conflict with the established scientific evidence.

Restrictions Targeting Abortion Providers

Most states require abortion facilities and other health care facilities to meet standards designed to ensure patient safety. However, some states have imposed specific standards for abortion providers that do little or nothing to improve safety, but significantly limit access to abortion. Those standards include measures that impose excessive physical plant requirements or require providers to have admitting privileges at local hospitals, such as in the Texas case; other restrictions ban the use of telemedicine for medication abortion and limit the provision of abortion to licensed physicians.

Ambulatory surgical center standards. Especially since 2010, states have moved aggressively to regulate the facilities where abortion services are performed to, in the words of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R), "protect innocent life, while ensuring the highest health and safety standards for women."4 All abortion regulations apply to abortion clinics, but some go so far as to apply to physicians’ offices where abortions are performed or even to sites where only medication abortion is administered. Eighteen states have abortion clinic standards in effect as of April 15 that are equivalent to those in place for ambulatory surgical centers, even though surgical centers tend to provide more invasive and riskier procedures, and use higher levels of sedation (see table).5–9 These standards as applied to abortion clinics often include onerous physical plant requirements, such as room size and corridor width, in the guise of ensuring patient safety in the event of an emergency.

These standards are one of the two types of so-called targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP) requirements that were at issue in the Texas case. After reviewing the evidence, the Supreme Court agreed with the conclusion that the surgical center requirement will neither promote better care, nor yield more positive outcomes. According to the Court, the evidence "supports the ultimate legal conclusion that the surgical center requirement is not necessary."1

Hospital admitting privileges. In its brief to the Supreme Court, Texas argued that the state had adopted the admitting privileges requirement to help ensure that women have easy access to a hospital should complications arise in the course of an abortion.10 In reality, however, abortion procedures are extremely safe: Fewer than 0.3% of U.S. abortion patients experience a complication that requires hospitalization.11 And in the unlikely event of an emergency, federal law requires a hospital to treat a woman, regardless of whether the abortion provider has admitting privileges at that facility. In its decision, the Court found no relationship between laws requiring admitting privileges at a local hospital and a state’s legitimate interest in protecting women’s health, and noted that Texas was unable to provide evidence "of a single instance in which the new requirement would have helped even one woman obtain better treatment."1

Barring telemedicine. Eighteen states have moved to ban the use of telemedicine to administer medication abortion7—often contending, as did the Iowa medical board, that the ban is needed "to protect the safety of women."12 This assertion, however, clearly contradicts a recent practice bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which says that "medical abortion can be provided safely and effectively via telemedicine with a high level of patient satisfaction."13 Notably, the Iowa Supreme Court cited that bulletin when it struck down the state’s telemedicine ban.14

Yet, at the same time that abortion opponents are lining up against allowing telemedicine for abortion services, the wider health community is increasingly looking to that same technology to improve access to care. For example, according to the American Hospital Association, telemedicine "is vital to our health care delivery system, enabling health care providers to connect with patients and consulting practitioners across vast distances."15 And in its release of ethical guidance in June 2016, the American Medical Association described telemedicine as "another stage in the ongoing evolution of new models for the delivery of care and patient-physician interactions."16

The irony of states’ attempts to ban telemedicine for medication abortion was on full display in a law enacted by Arkansas in 2015. Overall, the measure was aimed at encouraging the use of telemedicine as a way to improve the delivery and accessibility of health care by reducing barriers resulting from "geography, weather, availability of specialists, transportation and other factors."17 Nonetheless, the measure banned using this otherwise promising strategy for abortion services.

Allowing only physicians to perform abortions. In 38 states, the law permits only licensed physicians to provide abortions.5 Many of these laws date to the 1970s, when that was the widely accepted standard of care. That standard has changed over the decades, however, as advanced practice clinicians—such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners and certified nurse midwives—have been recognized as safe and effective providers of a wider array of services. In its 2012 guidelines, the World Health Organization concluded that trained advanced practice clinicians can safely provide abortion care.18 Studies looking at the performance of abortion in the United States support this conclusion. For example, a California study found that the complication rate for abortions performed by newly trained advanced practice clinicians was similar to that for procedures performed by physicians.19 Similarly, a study conducted in clinics in Vermont and New Hampshire found no significant difference in complications between abortions provided by physicians and those provided by physician assistants.20

Counseling and Waiting Period Requirements

Several states have adopted abortion counseling mandates that are in line with long-standing principles of informed consent; these measures require health care providers to give women complete, accurate and relevant information before obtaining an abortion, just as they must do for all other medical care.21 In other states, however, measures require that women be given information on the consequences of abortion that belie the scientific evidence. In addition, some states impose mandatory waiting periods on the basis of faulty premises.

Mental health. Six states require providers to inform women seeking an abortion that having the procedure can have serious mental health consequences;8 however, time and again, studies have shown that abortion does not increase women’s risk of mental health problems. For example, a 2008 review of the evidence conducted under the auspices of the American Psychological Association concluded that having an abortion is no different than continuing an unintended pregnancy to term.22 By sharp contrast, unintended pregnancy and childbearing has been linked to adverse mental health outcomes: Notably, in 2016, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force designated unintended pregnancy as a risk factor for depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period.23

Future fertility. A handful of states require that women be told that having an abortion can jeopardize their future fertility. Yet, several reviews of the available scientific literature affirm that vacuum aspiration—the method most commonly used during first-trimester abortions—poses virtually no long-term risk of future fertility-related problems, such as infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage or fetal anomaly.24,25 On the basis of this literature, ACOG concluded as recently as 2015 that the consensus among health care providers is that "one abortion does not affect your ability to get pregnant or the risk of future pregnancy complications."26 Although the evidence is less extensive, the literature also suggests that repeat abortion, in and of itself, poses little or no risk.24,25,27

Breast cancer. Counseling materials mandated in five states inform women that having an abortion could increase the risk of breast cancer.8 These requirements do not withstand scientific scrutiny. In 2003, the National Cancer Institute convened a workshop of over 100 of the world’s leading experts on pregnancy and breast cancer risk. After reviewing the available literature, the panel concluded that having an abortion "does not increase a woman’s subsequent risk of developing breast cancer."28 Another exhaustive literature review and analysis published in 2004 by a panel convened by the British government came to the same conclusion.29 This position has been affirmed by both the American Cancer Society30 and ACOG.31

Mandatory waiting periods. Twenty-seven states require women to wait between 18 hours and three days (not including weekends or holidays) after pre-abortion counseling before they can receive an abortion.8 These requirements are rooted in the idea that women need additional time to consider their decision. However, a nationally representative survey of abortion patients conducted in 2008 found that 92% of women reported that they had made up their mind to have an abortion prior to making an appointment.32 Another study, conducted at a large U.S. abortion clinic in 2008, found that 99% of abortion patients reported that they were "sure" or "kind of sure" of their decision to have an abortion, and 98% reported that it was "true" or "mostly true" that "abortion is a better choice for me at this time than having a baby."33

Restrictions Using Fetal Pain as a Pretext

Several states have used assertions that a fetus can feel pain at 20 weeks postfertilization (which is 22 weeks after the woman’s last menstrual period, often referred to as LMP) as a basis for either banning abortion after that point in pregnancy or informing women that an abortion could cause pain to the fetus.

Banning abortion at 20 weeks. Seventeen states have moved to ban abortions at or after 20 weeks postfertilization on the grounds that a fetus may be able to feel pain at or beyond that point. According to ACOG, however, "a human fetus does not have the capacity to experience pain until after viability,"34 a point which is generally not reached until after 24 weeks LMP. Moreover, a 2010 comprehensive review by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists concluded that "interpretation of existing data suggests that cortical processing and therefore fetal perception of pain cannot occur before 24 weeks of gestation."35 The researchers based their conclusion on evidence that connections from the periphery to the cortex, which are required for conscious perception of pain, are not intact before 24 weeks.

Informing women a fetus can feel pain. Thirteen states require that women seeking an abortion be informed that a fetus reacts to pain in the same way an adult or child would.8 In some of these states, the information is provided only to a woman who is seeking an abortion at 20 weeks LMP, whereas in others, the information is provided to any woman seeking an abortion; regardless, it is well before the point in pregnancy supported by the scientific evidence.

Quantifying the Laws’ Reach

All 10 of these categories of abortion restrictions conflict with rigorous science, and many of the restrictions have been shown to cause serious harm to women. When the Supreme Court struck down Texas’ abortion restriction last year, it said, "The record contains sufficient evidence that the admitting-privileges requirement led to the closure of half of Texas’ clinics, or thereabouts. These closures meant fewer doctors, longer waiting times, and increased crowding."1 In addition, the Court said that the evidence supports the conclusion that applying standards for ambulatory surgical centers to abortion clinics places "a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking an abortion."1

Similarly, imposing a waiting period on women seeking an abortion does little to promote informed consent, but it can have serious detrimental consequences. A survey of patients seeking an abortion in Texas after a mandatory 24-hour waiting period was implemented found that almost one-third reported that the waiting period had a negative effect on their emotional well-being.36 Moreover, a recent Guttmacher Institute study of women having an abortion found that women living in a state with a waiting period were more likely than women living in other states to have a delay of more than two weeks.37

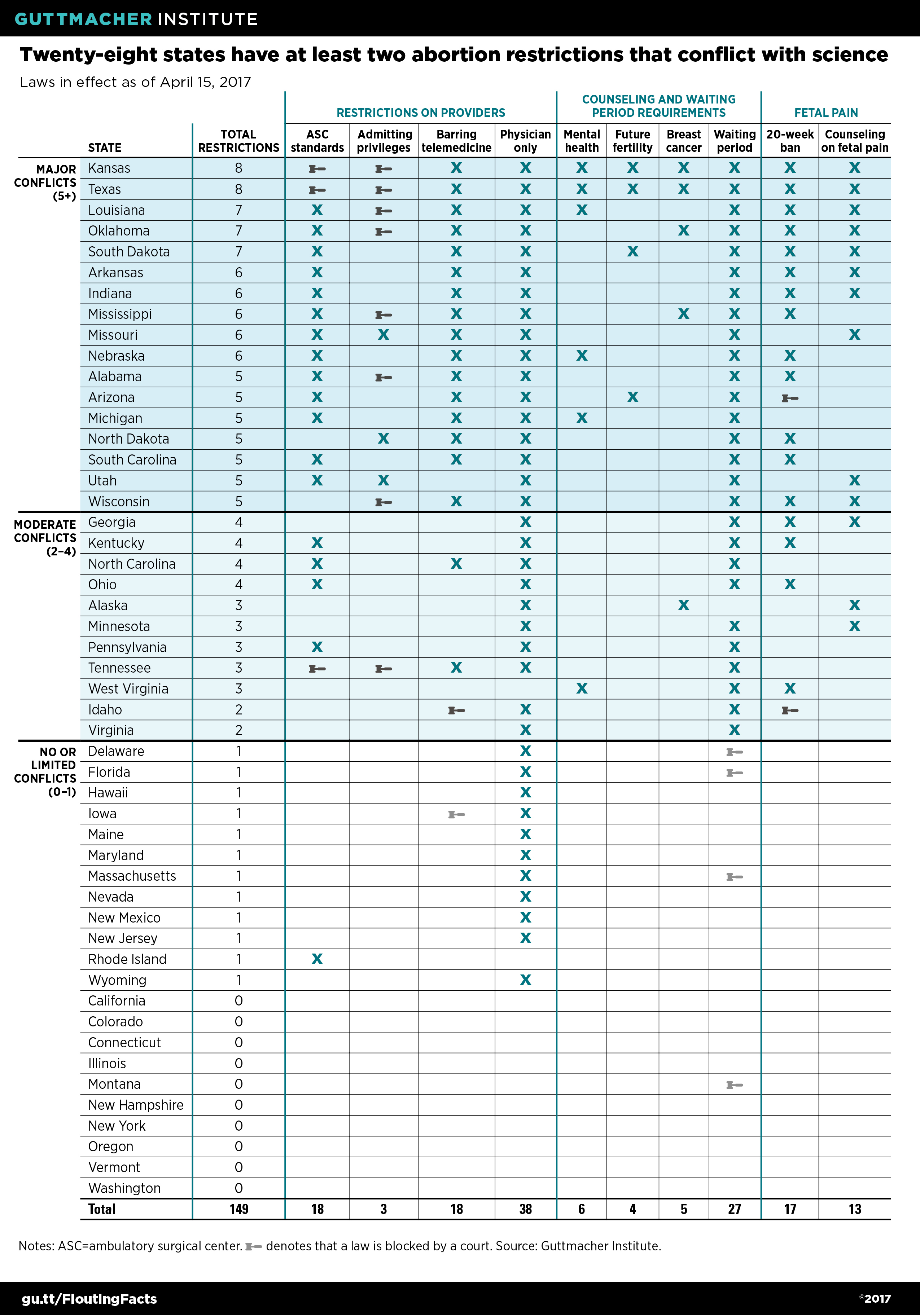

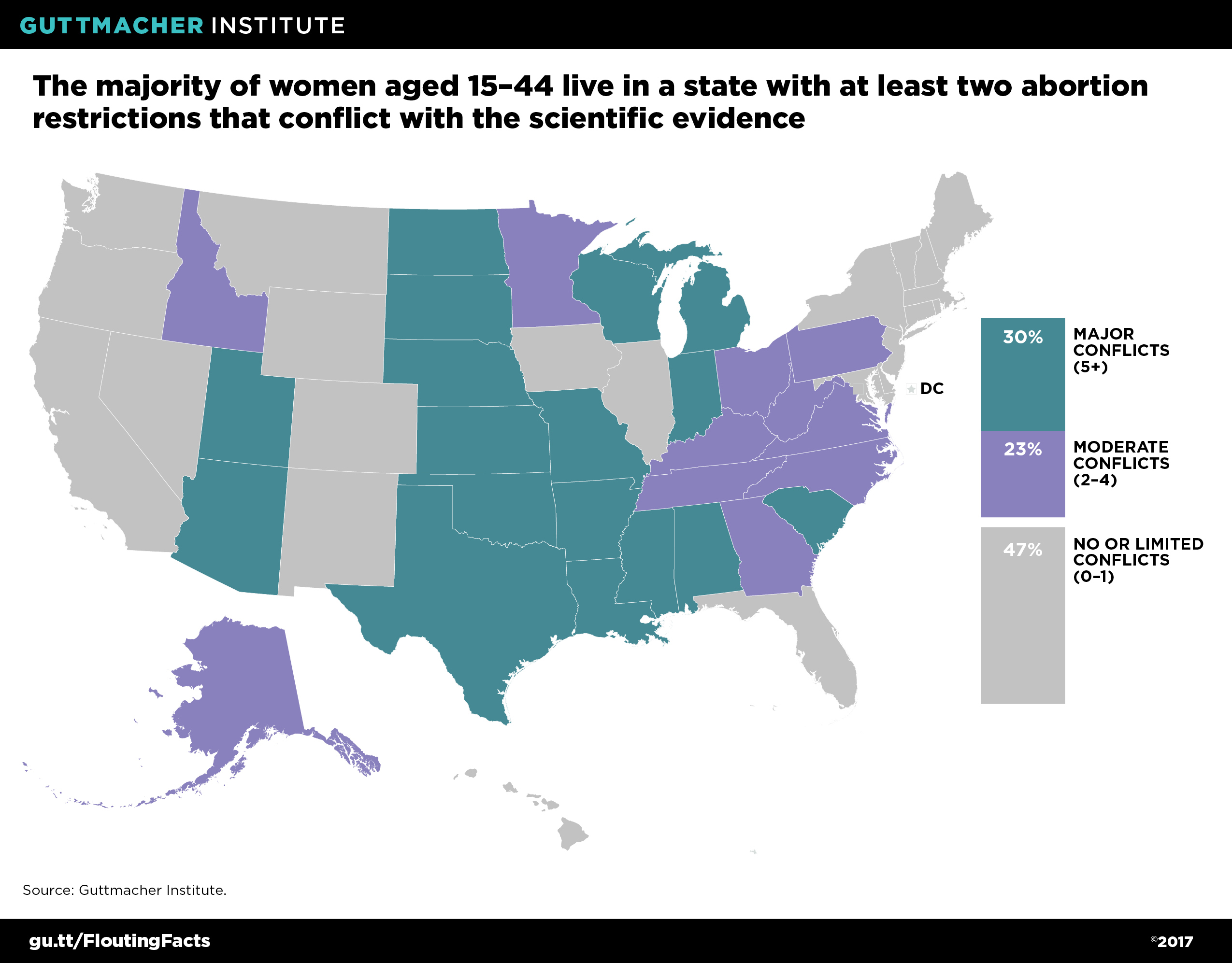

Nonetheless, provisions that flout the science are widespread. Although no state has a law in effect in each of the 10 major categories, Kansas and Texas have the dubious distinction of having eight (see table). Altogether, 17 states have major conflicts with the science, by having at least five types of restrictions in effect; 30% of all U.S. women of reproductive age live in these states (see map).38 (And, in fact, these numbers would be larger if laws that had been struck down through legal challenges were included: For example, if the two restrictions invalidated by the Supreme Court last year were counted, Texas would have a requirement in all of the 10 categories.)

Eleven states have moderate conflicts with the science, meaning that they have laws in effect in 2–4 of these types of major categories of restrictions. Notably, nearly all of these states restrict the provision of abortion to licensed physicians and require women to wait a specified period of time before having an abortion. Combined, more than half (53%) of U.S. women of reproductive age live in a state that has major or moderate conflicts with the science.38

Twenty-two states have none or only one of these restrictions. Most often, if a state has one restriction, it is a law that allows only licensed physicians to perform the procedure. Just under half (47%) of all U.S. women of reproductive age live in states with no or limited conflicts with the science.38

With so many U.S. women living in states where the laws on abortion conflict with the science, it would be easy to succumb to temptation to say that data and evidence no longer matter. But, in the face of this onslaught, sound science matters now more than ever, and supporters of reproductive health and rights need to push back against these spurious attacks. The current environment makes it critical to arm policymakers with the facts they need to adopt sound, evidence-based policies that support—rather than thwart—women’s efforts to get the care they need, and to overturn measures that clearly flout the facts.