Since 1996, more than $2 billion in federal funding have been spent on programs for young people that focus on promoting sexual abstinence outside of marriage ("abstinence-only"). Federal funding for these programs accelerated under the George W. Bush administration, then dropped significantly while President Obama was in office. During the Obama era, proponents of abstinence-only programs found themselves on the defensive: Politically, they could no longer look to the president for support for their ideologically driven agenda. As a practical matter, they were faced with a wealth of evidence that abstinence-only programs do not work to deter or delay sex among young people. And public opinion was not on their side, with a majority of the public in favor of sex education that includes information about contraception in addition to abstinence.1 Rather than reexamining their programmatic approach, abstinence-only proponents began to adopt a new rhetorical frame in an attempt to appeal to a wider audience and in preparation for a change in the political landscape.

With social conservatives now in control of both the White House and Congress, abstinence-only programs are poised for a dramatic comeback and federal funding for these programs is likely to see significant increases again. But despite some retooling, abstinence-only programs remain as flawed as ever.

Rebranding Abstinence-Only Programs

Over the past several years, proponents of abstinence-only programs have been working to enhance their brand and reframe their approach. One of the most significant changes has been to rebrand abstinence-only programs as "sexual risk avoidance" programs, based on the premise that young people should be held to a higher standard of behavior than merely risk reduction. Risk avoidance and risk reduction are two common public health prevention strategies that aim to address risk-taking behaviors—such as cigarette smoking and illicit drug use—and promote differing protective behaviors. Interventions can range from those that promote abstaining from the activity in the first place, returning to abstinence (cessation) or reducing individual risks if and when engaging in the activity.

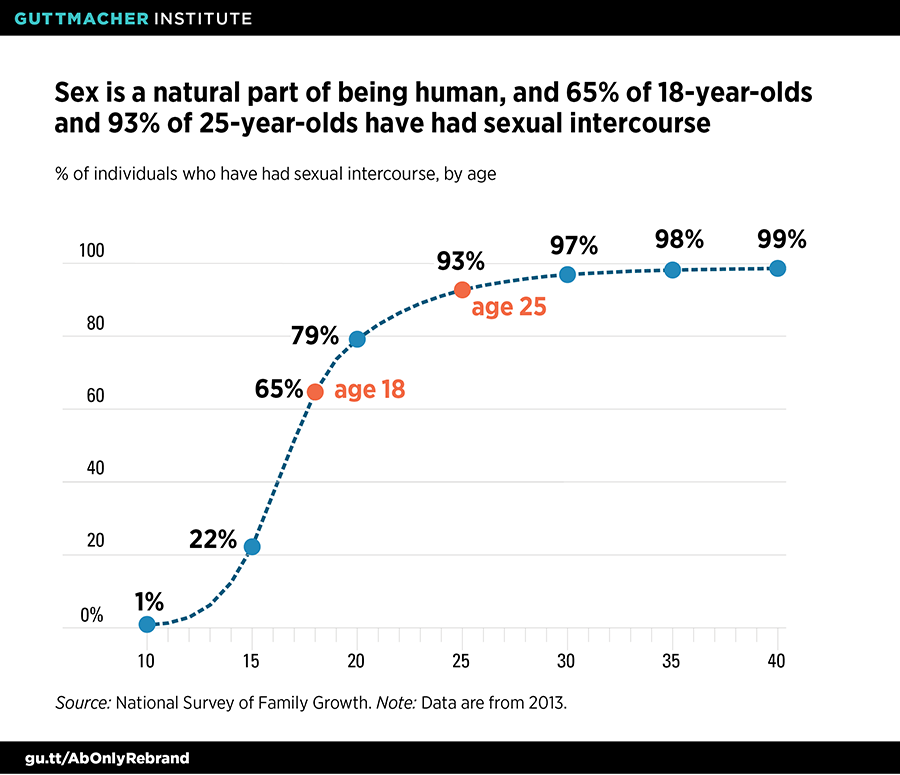

For activities that have inherent dangers that outweigh any potential benefits, such as cigarette smoking or drunk driving, this range of strategies makes sense. But sexual activity is not like many other risky behaviors, which can be prevented altogether. By contrast, sexual activity is a natural and healthy part of being human, and sexuality—far from being inherently harmful—can offer pleasure and intimacy throughout one’s life, not to mention the potential for having children.

Another part of the abstinence-only rebranding effort has been elevating the concept of "success sequencing for poverty prevention." Initially developed by analysts at the Brookings Institution, this view holds that the formula for escaping poverty is for young people to finish high school, work full time, and wait to get married and have children until at least age 21.2 Groups across the political spectrum have endorsed and adapted this concept, some by concluding that waiting until marriage to have sex enables young people to follow this model for success. Abstinence-only proponents have taken advantage of the currency of success sequencing to promote their programs as poverty prevention measures.

Abstinence-only proponents and programs have co-opted several other concepts as well. They have adopted terms such as "evidence-based" and "medically accurate and complete," and embraced language on "healthy relationships" and "youth empowerment," all of which are typically associated with programs that respect young people’s decision making. For example, even though abstinence-only programs may claim to promote "healthy relationships" and provide "youth empowerment," the terms are used in the context of federal program requirements that "ensure that the unambiguous and primary emphasis and context...is a message to youth that normalizes the optimal health behavior of avoiding nonmarital sexual activity."3 In 2012, the primary advocacy organization for abstinence-only programs, the National Abstinence Education Association (NAEA), dropped "abstinence" from its name altogether and rebranded itself as "Ascend." Nevertheless, most of the "sexual risk avoidance" curricula endorsed by Ascend are the same as the "abstinence education" curricula promoted by NAEA prior to 2012 and have the same goals.4–6

With social conservatives now in the White House, abstinence-only proponents are in positions of power within the administration. In June 2017, Valerie Huber, the former president and CEO of Ascend, was appointed chief of staff to the assistant secretary for health within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), with the authority to direct the work of offices charged with promoting sexual and reproductive health information and services.7

Proponents are using their new-found influence to revitalize and reshape federal abstinence-only programs. There are two such programs at the federal level. The first of these programs, created in 1996 under Title V of the Social Security Act, provided at its peak $75 million per year to states for programs that conformed to a highly restrictive eight-point definition of "abstinence education." Some of the more controversial components of this definition included teaching that "abstinence from sexual activity is the only certain way to avoid out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and other associated health problems" and that "a mutually faithful monogamous relationship in context of marriage is the expected standard of human sexual activity."8

The second federal abstinence-only program was a competitive grant program created by Congress in 2000 to bypass the states entirely and provide funding directly to community-based organizations. Under the George W. Bush administration, annual funding for the program—then called "community-based abstinence education" and explicitly tied to the same restrictive eight-point definition—ballooned from $20 million initially to $113 million at its peak. The program ended briefly after Obama came into office, but was revived in federal fiscal year (FY) 2012 at $5 million.

Both of these programs have been revised and renamed in recent years, but the goal remains the same: to implement programs exclusively focused on voluntarily refraining from sexual activity outside of marriage. First, in FY 2016, Congress renamed the competitive grant program as "sexual risk avoidance" and decoupled it from the eight-point definition of "abstinence education." To qualify for funding, programs must, among other things, "teach the benefits associated with self-regulation, success sequencing for poverty prevention," and "resisting sexual coercion…without normalizing teen sexual activity."9 Funding for the program has again started to increase, rising to $15 million in FY 2017 and likely to go as high as $25 million under House and Senate spending proposals for FY 2018.

In February 2018, the Title V abstinence-only program (which expired briefly in September 2017) was renewed for two more years at $75 million annually under the new name of "sexual risk avoidance education."10 Congress eliminated the "abstinence education" definition, replacing it with similarly motivated topics that the program must address, including "the advantage of refraining from nonmarital sexual activity in order to improve the future prospects and physical and emotional health of youth"; "the increased likelihood of avoiding poverty when youth attain self-sufficiency and emotional maturity before engaging in sexual activity"; and in the context of preventing sexual coercion and dating violence, "recognizing that even with consent teen sex remains a youth risk behavior." Additionally, the program specifies information that must be withheld from students, requiring that "the education does not include demonstrations, simulations, or distribution of contraceptive devices."10

Same Inherent Flaws

Despite efforts to rebrand abstinence-only programs, these approaches remain just as harmful as in the past. Abstinence-only programs are ineffective at reaching their primary goal of keeping young people from engaging in sexual activity as well as at meeting the needs of all adolescents. They also create barriers for young people in making informed decisions about their health, require unethical behavior from educators, perpetuate inequities and discrimination and promote stigma against marginalized individuals and toward sex more generally in society.

Ineffective at their primary goal. Even judging the abstinence-only approach on its own limited terms—where the only thing that matters is stopping or even delaying sex outside of marriage—this approach is ineffective. The first federally funded evaluation of Title V abstinence-only programs, conducted in 2007 by Mathematica Policy Research on behalf of HHS, found no evidence that these programs increased rates of sexual abstinence.11 In fact, according to scientific evidence amassed over the past 20 years, abstinence-only programs do not have a significant impact on the age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners or other sexual behaviors.12 Further, abstinence-only programs may place young people at increased likelihood of pregnancy and STIs once they do become sexually active.11,13,14

Fail to meet the needs of young people. By withholding potentially life-saving sexual health information and skills, abstinence-only programs do nothing to prepare young people for when they will become sexually active and systematically ignore the needs of those who are already sexually active.12 Specifically, abstinence-only programs typically overlook or downplay the benefits of contraception and often overemphasize its relative risk. These programs may be doing long-term damage by deterring condom and other contraceptive use among sexually active adolescents, increasing their risk of unintended pregnancy and STIs. In addition, abstinence-only programs typically fail to provide education and skill building on the complete scope of critical sexual health and sexuality topics, such as healthy relationships, communication and consent.

In the United States, two-thirds of 18-year-olds have had sexual intercourse, and nine in 10 people have by their mid-20s (see figure).15 Despite this reality, only 57% of sexually active young women and 43% of sexually active young men have received formal instruction about birth control methods before having sex for the first time,16 and even fewer have presumably received complete and accurate information. These figures demonstrate the need to increase access to sexual and reproductive health information, rather than withholding or distorting it through the lens of an abstinence-only approach.

Violate ethical principles. Teachers, health educators and health care providers have ethical obligations to provide accurate information to their students or patients and to not withhold information as a way of influencing their choices.17,18 According to the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine’s 2017 position statement on abstinence-only programs, "the withholding of information on contraception or barrier protection to induce the adolescent to become abstinent is inherently coercive."19 Abstinence-only interventions restrict professionals from fulfilling their ethical responsibilities to provide complete and accurate information by requiring them to emphasize condom and contraceptive failure rates and prohibiting instruction on how to access or use contraceptives effectively.17,18 An approach that inherently excludes the full range of information on contraception or other sexual health topics—or provides it in a misleading manner—is ethically problematic.

Perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes and discrimination. Research has long established that gender inequities—and the ideologies that uphold them—have an impact on sexual and reproductive health outcomes, including HIV and other STIs, unintended pregnancies and sexual violence.20,21 Through the actual curricula materials or their implementation, many abstinence-only programs teach gender stereotypes as facts.22 These programs commonly reinforce stereotypes about feminine passivity and sexual restraint, while linking masculinity with an intense sex drive, lack of emotional involvement and aggressiveness.23–25 This perpetuation of stereotypical gender roles has been shown to impede women’s sexual autonomy while also having negative health consequences for men.22 Moreover, abstinence-only programs persist in relying on unequal and outdated perceptions of gender roles at a time when there is movement in some segments of society to examine and improve gender dynamics in the workplace and beyond.

In addition to promoting gender stereotypes, abstinence-only programs fail LGBTQ youth. Although nationally representative data on these young people remain limited, 2015 data indicate that at least 8% of high school students identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual.26 While some abstinence-only programs no longer explicitly condemn same-sex relationships, they still emphasize heterosexual relationships as the expected societal norm and not only ignore, but often undermine, the sexual health and overall well-being of LGBTQ youth.12,27 In addition to being excluded within an abstinence-only program, LGBTQ youth may face outright discrimination, which "can contribute to health problems such as suicide, feelings of isolation and loneliness, HIV infection, substance abuse, and violence."12

Stigmatize sex, sexual health and sexuality. Sexual development and sexuality are fundamental parts of being human, yet abstinence-only programs deliberately promote judgment, fear, guilt and shame around sex. These programs frame premarital sexual activity and pregnancy as wrong or risky choices with negative health outcomes and seek to shame sexually active young people and young parents.28

Although abstinence-only proponents may not intend it, by stigmatizing sex outside of marriage, they also stigmatize survivors of sexual assault and coercion. In 2015, 11% of high school students experienced physical or sexual dating violence, with disparities by sex, race and ethnicity.29 Abstinence-only programs can fail to equip young people with education for all genders essential to not just preventing abuse and harassment but also promoting healthy relationships, and often blame young people who have experienced circumstances beyond their control.

Ignore systemic inequities in defining "success." Abstinence-only programs seek to prescribe a single life path for young people, the "success sequence for poverty prevention," while ignoring systemic inequities—such as racism, inequality, discrimination and trauma—that contribute to poverty and also influence adolescent sexual and reproductive health.22,30 In fact, several Brookings Institution researchers have critiqued the success sequence as too simplistic and resulting in "more success for whites than blacks."31 According to those researchers, "the hurdles are clearly higher for some groups—especially black Americans—than others. And the pay-offs from following the success sequence clearly differ by race."31

Abstinence-only proponents argue that the message of abstinence outside of marriage is one that resonates with all young people and therefore addresses the needs of marginalized populations. But in fact, by focusing on a single life path for success, abstinence-only programs stigmatize young people for whom this specific set of prescribed goals may not be desired or obtainable. Ultimately, abstinence-only programs fail to take into account the structural barriers, cultural differences and individual choices and experiences that shape people’s lives.

The Wrong Approach

In spite of these fundamental flaws, the Trump administration and social conservatives in Congress continue to call for dramatic increases in funding for abstinence-only programs (see "The Looming Threat to Sex Education: A Resurgence of Federal Funding for Abstinence-Only Programs?" 2017). This is in line with other ideologically motivated attacks on evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs and on sexual and reproductive health and rights more broadly in an effort to promote a coercive agenda (see "Coercion Is at the Heart of Social Conservatives’ Reproductive Health Agenda," 2018).

This effort to reinvigorate federal abstinence-only programs is dangerous and counterproductive. For decades, abstinence-only programs have failed to meet the needs and uphold the rights of young people. A name change and claims of raising the standard of behavior for all young people do nothing to correct these flaws. Young people deserve more than the same programs under a new name; it is past time to end federal funding for abstinence-only programs.