The full realization of sexual and reproductive health and rights globally requires a deeper and more nuanced understanding of individuals’ contraceptive needs and desires, and the range of barriers that may impede their ability to act on these freely. Developing and refining measures that encompass the range of existing contraceptive needs is one critical step in this process. The time has come to better align our measurement practices with our values—ensuring that indicators of progress on sexual and reproductive health are increasingly grounded in the rights and autonomy they purport to advance.

Adding It Up 2024, a key Guttmacher Institute study, uses a new lens to estimate contraceptive need, aligning with broader changes across our field to move toward measurement approaches that directly capture each person’s sexual and reproductive health needs and experiences.

Expanding Measures of Contraceptive Need in Adding It Up

Adding It Up (AIU), a research initiative led by the Guttmacher Institute for more than two decades, has been a key resource for information on the need for, costs of and impacts of providing contraceptive care and other sexual and reproductive health services in low- and middle-income countries. Historically, contraceptive need analyses in AIU have focused on unmet need for modern contraceptive care. This key indicator has been central to driving increased financing and improved access to contraception by drawing attention to the critical gaps in meeting people’s contraceptive needs around the world. However, this indicator has at times been misused and misinterpreted, and there are growing calls to develop new measures of contraceptive need that are more rights based and person centered.1

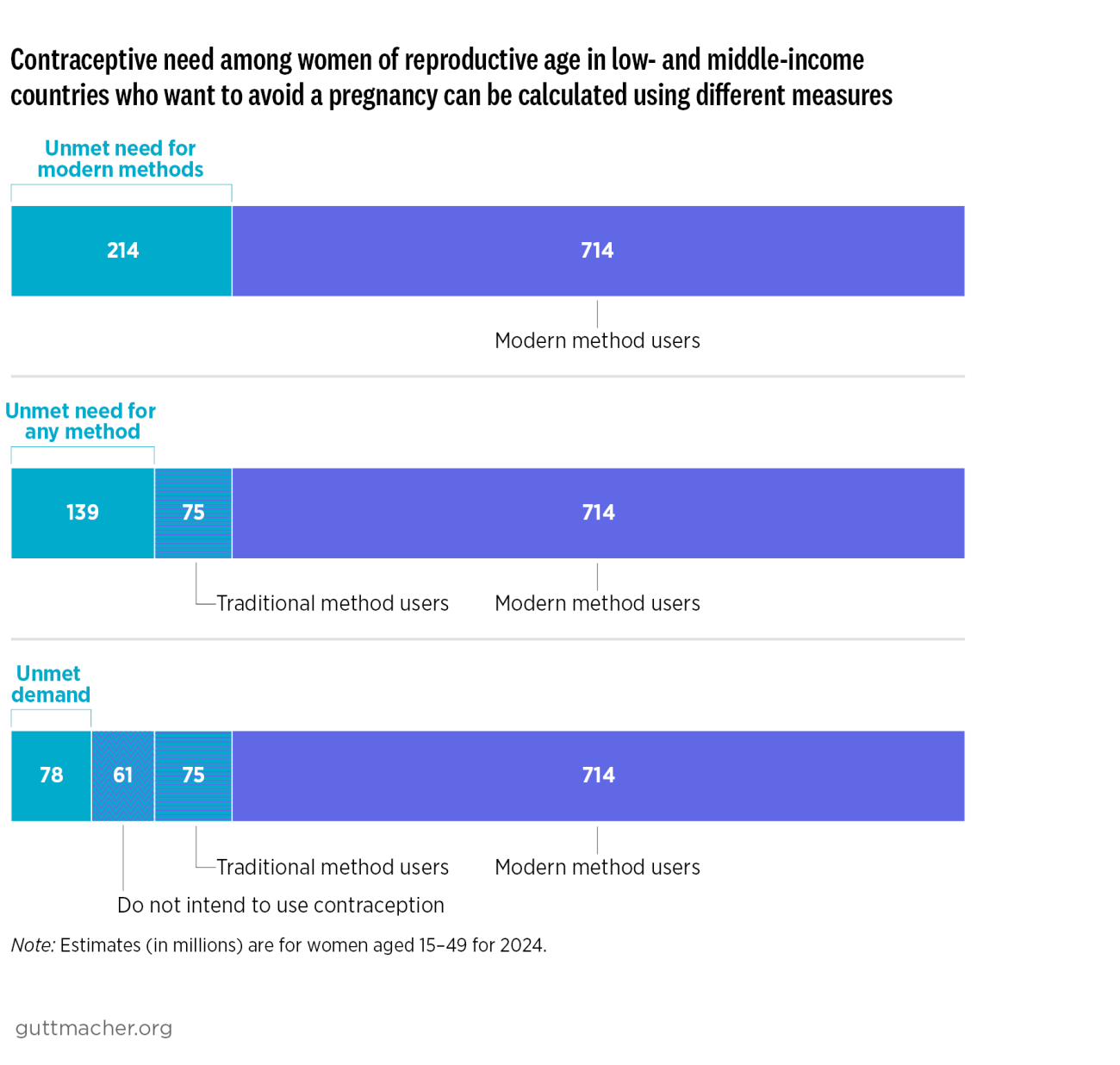

The latest AIU release (with 2024 estimates)2 includes calculations based on three different measures of contraceptive need: unmet need for modern methods; unmet need for any method, which has been used in the field already for estimating service gaps; and a newer measure called “unmet demand,” which focuses on the most critical gaps in the need for contraceptive care and centers women’s own expressed needs and preferences.

In this explainer, we walk through the reasons for developing a new measure, how the new measure of unmet demand is defined and compares with other commonly used measures, and why this newest measure serves as a valuable addition to existing indicators of contraceptive need to support global family planning advocacy.

Why Use a New Measure of Unmet Need for Contraception?

Long-standing indicators of contraceptive need, such as unmet need for modern methods, have included assumptions about contraceptive need based solely on women’s pregnancy desires. The measure of unmet need for modern contraception assumes that if women say they want to avoid a pregnancy in the next two years or do not want any(more) children, they should be using a modern method of contraception. The measure does not consider whether women want or need contraception, if they intend to use contraception or if there is a modern contraceptive method available that they would find acceptable to use.

In addition, focusing on unmet need for modern methods centers modern contraception as the only acceptable means to successfully avoid pregnancy. Many people choose to use traditional methods of contraception—such as calendar rhythm or withdrawal—and may be satisfied with that choice.* Although modern methods are generally more effective at preventing pregnancy,3 traditional methods can still substantially reduce the chances of unintended pregnancy and some people are able to use these methods effectively.

The measure of unmet need for any method removes the assumption that modern contraceptive method use is the only way to meet an individual’s contraceptive needs and preferences.4 Metrics of unmet need can be useful for understanding how many people want to avoid pregnancy and are not using (modern or any) contraception, but they do not establish who wants to use contraception.

Person-centered measurement approaches strive to be rights based, centering bodily autonomy and developing indicators to capture a person’s own expressed preferences, needs and values, and whether they feel that their needs are being fulfilled.5 The family planning field needs new indicators that are more person centered to complement previous metrics and better reflect gaps in contraceptive need.