This report presents an analysis of policies and curricula on sexuality education in Ghana and their implementation in senior high schools, focusing on three geographically diverse regions: Greater Accra, Brong Ahafo and Northern.

From Paper to Practice: Sexuality Education Policies and Their Implementation in Ghana

Key Points

- Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) education is a key component in a multifaceted approach to address the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents.

- In senior high schools, SRH education topics are integrated into two core and two elective subjects, but those in the core subjects are limited in scope, and the overall approach emphasizes abstinence.

- Three-fourths of students were exposed to at least one topic in five key categories related to SRH education; only 8% of students reported learning about all of the topics that constitute a comprehensive curriculum according to international guidelines.

- Nearly all students had learned about abstinence, HIV, reproductive physiology and SRH rights in their classes; fewer than half had learned about contraceptive methods and practical skills, such as communicating in relationships, where to access HIV or STI services, how to use contraceptives or where to get them.

- Teachers reported challenges to teaching SRH topics effectively, including lack of time, lack of appropriate skills and inadequate teaching materials.

- Overall, schools in Ghana are implementing an advanced program compared with programs in other countries in the region. Yet broadening the range of topics to reflect international guidelines and promoting practical skills related to contraceptive use would improve the comprehensiveness and impact of the program, and better integrating topics into core subjects would standardize the information that all students receive.

- Improving and systematizing teacher training, and diversifying teaching approaches to encourage active student participation and promote practical skills, confidence and agency, are essential if SRH education is to be delivered accurately and effectively.

- Further steps should be taken to demystify and desensationalize sexuality among adolescents, and continued sensitization of the community, teachers and school heads is needed to ensure that adolescents are supported in learning SRH-related skills.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Timely provision of accurate and comprehensive information and life skills training regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights is essential for adolescents to achieve sexual health and rights and avoid negative health outcomes.1–3 While sexuality education is just one component in a multifaceted approach to address, and ultimately improve, the sexual and reproductive lives of young people, it provides a structured opportunity for adolescents to gain knowledge and skills, to explore their attitudes and values, and to practice the decision making and other life skills necessary for making healthy informed choices about their sexual lives.4–10 Abstinence-only education programs have shown little evidence of improving sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes.11,12 In contrast, comprehensive sexuality education programs that recognize that sexual activity can occur during adolescence, that seek to ensure the safety of such behavior and equip students with the knowledge and ability to make informed choices (including to delay sex), and that focus on human rights, gender equality and empowerment have demonstrated impact in several areas: improving knowledge, self-confidence and self-esteem; positively changing attitudes and gender and social norms; strengthening decision-making and communication skills and building self-efficacy; and increasing the use of condoms and other contraceptives.13–19

Adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health

Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents is a priority for program planners and policymakers in Ghana. Despite efforts targeting young people, recent studies suggest a persistent need for SRH information and services, further emphasizing the need for high-quality sexuality education.

Sexual activity

Nationally, many adolescents (those aged 15–19), whether married or not, have had sexual intercourse (43% of females and 27% of males), and 26% and 14%, respectively, are currently sexually active (Table 1.1).20 In Ghana, the median age at first intercourse is 18 for females and 20 for males, and among adolescents, 12% of females and 9% of males had initiated sex before the age of 15. In the three geographic regions included in the current study, a greater proportion of adolescent females had had sex before age 15 in Brong Ahafo (21%) than in Greater Accra (5%) or Northern (8%); among adolescent males, 23% had had sex before this age in Greater Accra, as had only 7% in Brong Ahafo and 3% in Northern.

Contraception, unplanned births and abortion

Contraceptive use is relatively low among adolescents in Ghana. Although 96% of females aged 15–19 have heard of at least one modern method, only 30% of those who are sexually active are currently using any contraceptive method, and 22% are using a modern one. Half of sexually active adolescent females in Brong Ahafo use a modern method (51%), as do 24% in Greater Accra and only 2% in Northern. Ninety-five percent of sexually active adolescent females who are unmarried want to avoid pregnancy within the next two years, but 62% have an unmet need for family planning, meaning they either want to postpone their next birth by at least two years or do not want any (additional) children, but are not using a method. Fourteen percent of all adolescents in Ghana have begun childbearing (i.e., have had a live birth or are currently pregnant), and three-quarters of their births in the past five years were reported as unplanned. This proportion was much lower in the Northern region (16%) than in Brong Ahafo (77%) or Greater Accra (72%). There is also evidence that adolescents are particularly vulnerable to having unintended pregnancies that result in abortions. Results from the Ghana Maternal Health Survey of 2007 show that 16% of pregnancies among those younger than 20 ended in abortion, whereas fewer than 10% of pregnancies among older women resulted in abortion.21

HIV prevalence and AIDS

There have been extensive media campaigns promoting HIV and AIDS awareness throughout Ghana. In addition, HIV prevention education has been incorporated into the school system and after-school programs. According to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS), 64% of females and 84% of males aged 15–19 know where to get condoms, but only 18% and 25%, respectively, have comprehensive knowledge about HIV and AIDS.* 20 Knowledge varies considerably by gender and region: Males are more likely than females to report having comprehensive knowledge, and adolescents in Greater Accra demonstrate higher levels of knowledge than those in Brong Ahafo and Northern regions. Nationally, HIV prevalence has been lower than in other countries in the subregion, never exceeding 3.6% (reported in 2003). Rates of HIV infection among 15–24-year-olds over the years have remained below the national average, except in 2014, when the rate of 1.8% for this age-group surpassed the national average of 1.6%.22 Data from the 2014 GDHS show that HIV prevalence is higher among women aged 15–24 than among their male counterparts (1.5% vs. 0.2%).20

The need for sexuality education in Ghana

The foregoing indicators point to the diverse SRH needs of adolescents across Ghana, as well as to the relevance and necessity for comprehensive sexuality education prior to the start of sexual activity. In recognizing that improving adolescents’ access to high-quality information and services is essential for ameliorating negative health outcomes, key stakeholders in Ghana have proposed policies and programs regarding adolescent sexual and reproductive health, including those related to sexuality education. The Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service have collaborated with key agencies, notably the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Service, to provide sexuality education in schools. Topics related to SRH are integrated into core and elective subjects, and as co-curricular activities.23 Although a range of these topics is included in primary, junior high and senior high school curricula in Ghana, the topics are limited in scope—there is a major focus on abstinence and, in some cases, a fear-based or negative perspective on sexuality. The policy environment and program structure are discussed in Chapter 3.

Scope of this report

Reviews of policies and curricula pertaining to sexuality education have shown that while many countries have established curricula, little is known about their use in schools—the degree of implementation, the mode and quality of the instruction, the existence of program monitoring and evaluation tools, the adequacy and quality of teacher training, the level of support for or opposition to the subject, and the effectiveness of existing programs in achieving desired knowledge and behavioral outcomes among students.10,24–27 This report provides a detailed snapshot of how the policies related to sexuality education in Ghana are translated into practice and what students, teachers and heads of schools think about them. Data from official documents, key informant interviews and school-based surveys were used to examine how sexuality education programs in three regions were developed, implemented and experienced. This report presents findings on the development of policies and curricula, including the actors involved and challenges faced; how sexuality education is taught in classrooms; students’ experiences and preferences; support for implementation, including teacher training and school environment factors; sources of SRH information outside of the classroom; and general opinions about such education among key stakeholders. The information presented is intended to provide the Ghana government and other stakeholders with a better understanding of sexuality education in schools, and ultimately to improve the quality and effectiveness of such education for both teachers and students.

CHAPTER 2: STUDY METHODOLOGY

The study on which this report is based was conducted as part of a multicountry study to assess the implementation of sexuality education in four countries from two regions (Latin America and Africa): Peru, Guatemala, Ghana and Kenya.† In each region, one country was chosen that is at a relatively more advanced implementation stage with its sexuality education program (Peru and Ghana), and another was chosen that is at an earlier stage (Guatemala and Kenya); these selections were based on reviews of policy documents and curricula, program evaluations and other regional reports,10,19,24,28 as well as consultation with stakeholders and research partners. While a major aim of the overall study is to compare all four countries, this report presents findings only for Ghana.

Study objectives

The goal of this study was to provide a robust, comprehensive analysis of policies and curricula regarding SRH education in Ghana and their implementation in secondary schools, with a focus on three geographically and ethnically diverse regions: Greater Accra, Brong Ahafo and Northern. Specific objectives included documenting policies and curricula on SRH education, describing the implementation of these, assessing the comprehensiveness of the content, examining the opinions and attitudes of students and teachers regarding such education, and providing recommendations to inform the design and implementation of such programs in schools in Ghana and beyond.

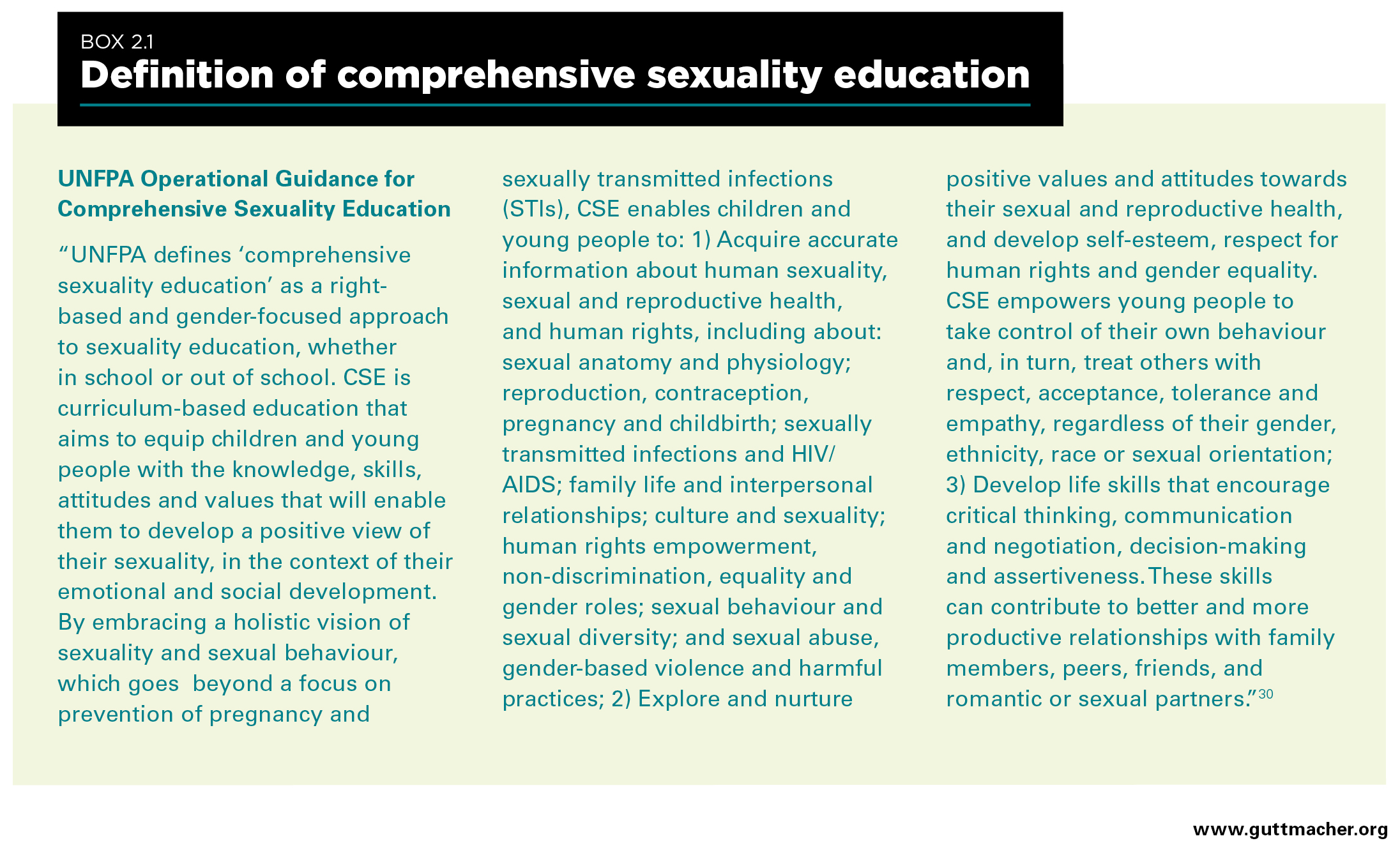

Defining comprehensive sexuality education

The terminology used to describe sexuality education varies across countries; in Ghana, the term sexual and reproductive health education is widely employed, and we therefore use that terminology when referring specifically to Ghana throughout this report. While different definitions of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) have been developed over time,4,5,7,29 this study used the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) definition‡ (Box 2.1). On the basis of the UNFPA definition, this study explored SRH education in Ghana according to three dimensions: information and topics covered, values and attitudes nurtured, and life skills developed.

Assessing the comprehensiveness of topics offered

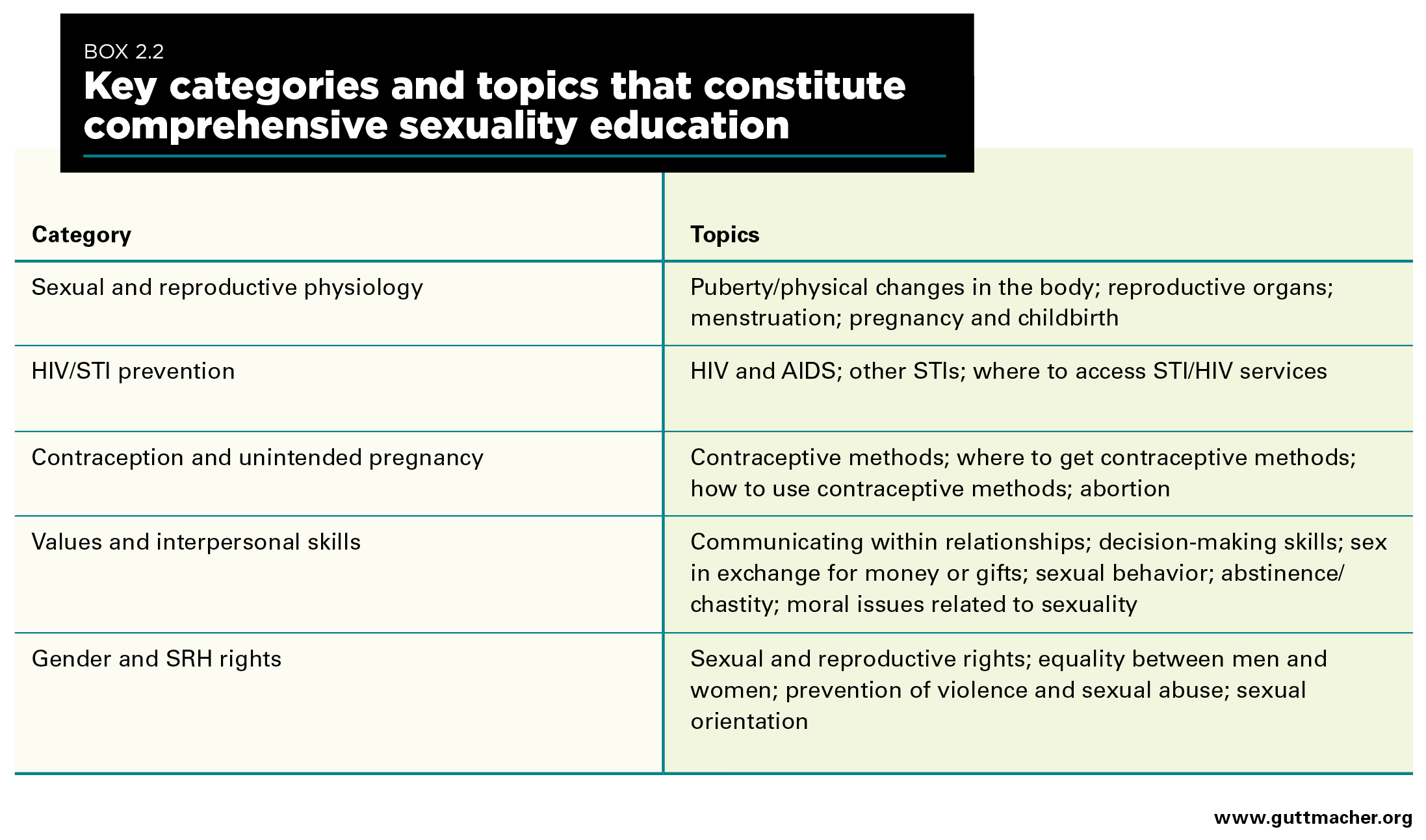

Because one aim of the study was to measure the comprehensiveness in the range of topics offered, we assessed this range according to international standards, in order to provide a baseline measure for developing policies or curricula in the future. The topics considered in this study reflect a broad approach that could reasonably be expected in Ghana, given cultural contexts. For example, we did not include topics such as sexual pleasure or desire, which are not culturally appropriate in the country setting. We did include abstinence, as this approach persists in many developing (as well as some developed) countries. Using various international guidelines, we identified five topic categories as key components of a comprehensive program (Box 2.2). The presence or absence of the topics in each category was used to measure comprehensiveness in the range of topics offered. We defined three levels: minimum, adequate and high. If at least one topic in each of the five categories was included, the range met at least a "minimum" level.§ If nearly all topics (except one at most) in each of the categories were included, the range was considered at least "adequate." The range was deemed to meet a "high" level of comprehensiveness if all topics in each category were included. These levels of comprehensiveness are not mutually exclusive; for example, schools that meet an "adequate" level also meet the "minimum" level, but will be categorized at the highest level achieved.

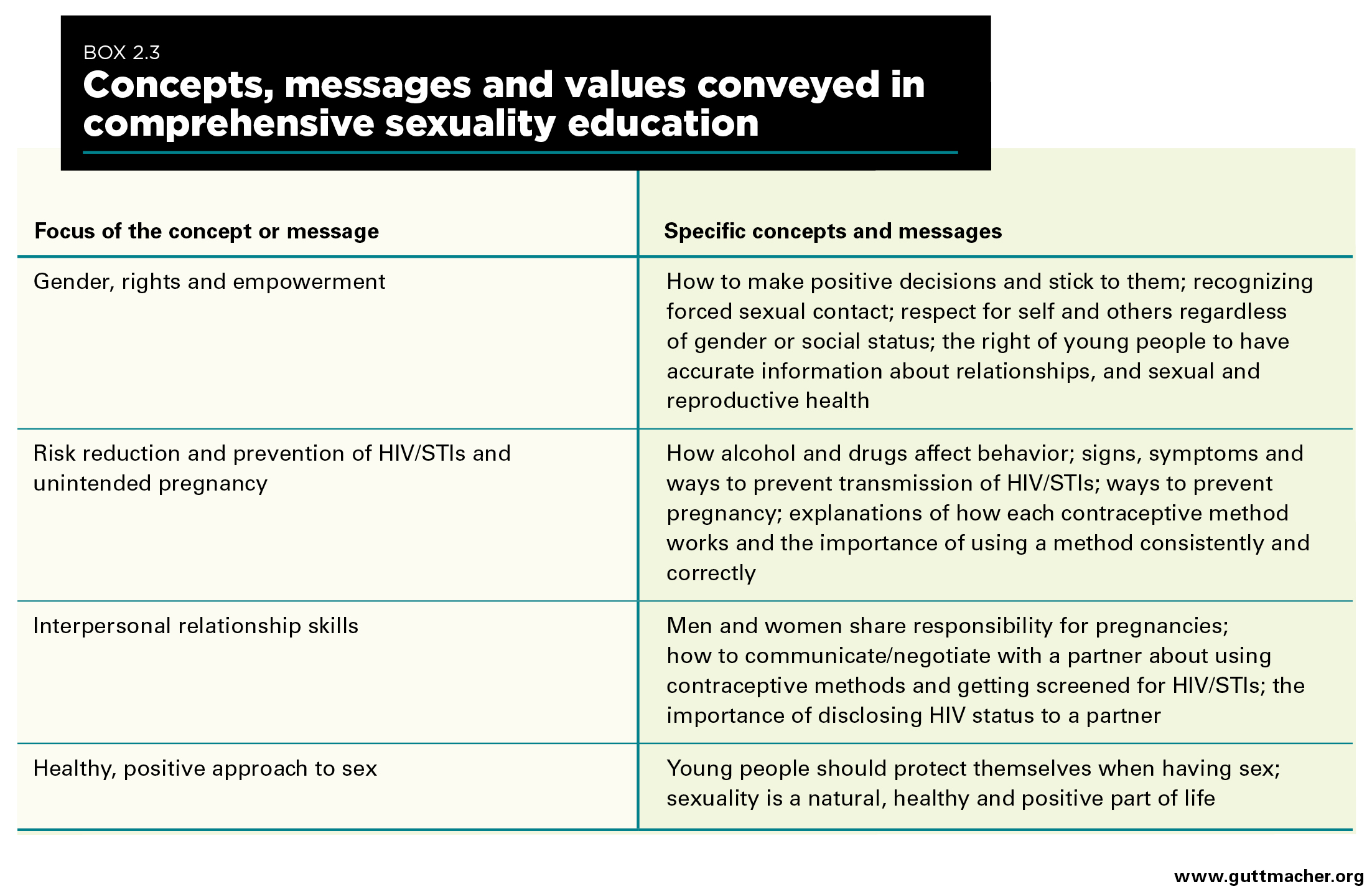

In addition to these topics, our study examined concepts and messages that may be delivered—and the values, attitudes and life skills nurtured—as part of a comprehensive approach to SRH education (Box 2.3). These elements focus on gender, rights and empowerment, risk-reduction skills, interpersonal relationships and positive views on healthy sexuality. To gain a more nuanced understanding of what is taught in the classroom and the tone in which the teaching is delivered, we assessed, among both students and teachers, the extent to which the concepts and messages were emphasized. We did not, however, include these concepts in our measure of comprehensiveness in the range of topics.

Limitations of the comprehensiveness measure

The measure we developed addresses only the range of topics taught, not other essential components that may determine the comprehensiveness of an SRH education program, such as integration of youth and community engagement into curriculum development, use of participatory teaching methods, safety of the learning environment, and links to SRH services and other initiatives that address adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues.5,31,32 Moreover, the measure does not assess the depth or manner in which a topic is addressed. For example, our measure assessed whether a school teaches about contraception, but did not capture the accuracy of information, the value judgments conveyed or the time spent teaching about contraception.

Study design

This cross-sectional assessment evaluates the implementation of SRH education in three regions in Ghana. In addition to reviewing existing policies, curricula and other documents regarding adolescent sexual and reproductive health, the study collected data from three sources.

In-depth interviews with key informants. Informants were asked about their views on current SRH education policy; opinions about the design, structure, coverage and content of the program; experiences implementing it in the school system, including how to better support it and challenges faced; perceived sources of support for or opposition to implementation at the national, regional and school levels; and monitoring and evaluation frameworks in place.

Survey of senior high school heads and teachers. Researcher-administered surveys elicited participants’ responses regarding the content of the curriculum; approach and format of SRH education in schools; teacher and student assessment methods; teacher training and support; school environment and perceptions of support for or opposition to the subject; and attitudes toward sexuality and SRH issues.

Survey of senior high school students. Self-administered surveys assessed students’ exposure to SRH education; preferences regarding content, teaching approach and format of the information received; level of support for or opposition to sexuality education in schools; and attitudes toward SRH issues.

Sampling strategy

Key informant interviews

Twenty-five key informants were identified through consultation with a wide range of stakeholders involved in policy making, program implementation or advocacy regarding SRH education. Informants included Ministry of Education staff involved in the development of policies and curricula related to SRH education, as well as national stakeholders and individuals with international agencies and NGOs involved in implementation. Also included were individuals working for groups advocating for or opposing the provision of SRH education in schools, and leaders of community organizations (e.g., youth associations), parent-teacher associations, women’s groups and religious groups.

Survey of schools

Selection of regions. For the school-based quantitative survey, a multistage sampling process was adopted. The first stage involved the selection of three out of Ghana’s 10 regions, to represent geographically, ethnically and economically diverse areas. In accordance with the methodology used by the Ghana Statistical Service, the country was divided into three zones:

- Southern (regions that have coastal strips): Western, Central, Greater Accra and Volta;

- Middle (regions in the forest zone): Eastern, Ashanti and Brong Ahafo;

- Northern (regions in the northern savannah zone): Northern, Upper East and Upper West.

One region was selected from each zone. In the Southern zone, Greater Accra was purposively selected because it includes the national capital and, therefore, decision makers at the national, regional and local levels. For the other two zones, Brong Ahafo and Northern were randomly selected.

Selection of schools. The second stage involved the selection of schools in the three regions. Because the study targeted students aged 15‒17, surveys were conducted in senior high schools.** Eighty-two schools were selected (Table 2.1); this number was based on a minimum required sample of 2,500 students, and a low-end estimate of 35 eligible students per school, using typical school and grade sizes.†† For each region, the sample was stratified by school type (public or private) and coeducational status (mixed gender, females only or males only) to ensure a representative sample.‡‡ The six single-sex schools in each region were purposively selected.

Of these 82 schools, 13 were dropped from the original sample and replaced—seven in Northern (including two single-sex schools), four in Greater Accra and two in Brong Ahafo—for reasons such as being on break during the survey period or not having enough students between the ages of 15 and 17. Only two of the 13 schools were replaced because of refusal to participate: One was a private, all-male seminary school in the Northern region that did not allow questions about sexuality to be asked, and one was a public school in Greater Accra that refused because it had not received a letter from the regional director of education.

Selection of school heads and teachers. In each of the schools, the head of the school (or the assistant head if the head was not available) was automatically selected to complete the survey. In four schools, the heads or assistant heads were unable to make time after two or more researcher requests, and therefore only 78 schools are represented for indicators that rely on information from the school heads. Teachers were selected on the basis of their involvement in teaching SRH education topics to students in Form 2 or 3 (i.e., the second and third years of senior high school). Since these topics are integrated into biology, social studies, integrated science and management in living, teachers of these subjects were targeted in each sampled school. These teachers were identified through consultation with the school head, and up to five teachers per school were selected on the basis of availability on the day of the survey and an aim to cover the range of different subjects. In one school, no teachers were available, so only 81 schools are represented for indicators that rely on teacher-level data.

Selection of students. All students in Forms 2 and 3 and aged 15–17 were eligible for selection. These students were selected because they were likely to have been exposed to at least one year of SRH education in high school and could therefore provide the information we sought to collect. Although this age range was targeted, students aged 13–14 and those older than 17 who were in Form 2 or 3 were not excluded from participating. One percent of students who participated were either younger than 15 or older than 17; three students—one in each region—refused to participate. To ensure equal representation of each school within its region, the number of sampled students per school was proportionate to school size. To minimize potential bias, all eligible students registered in Forms 2 and 3 at each school were gathered in a room and a ballot box was used to randomly select the desired sample of students. In one school, only one student was available at the time of the survey, so no student survey was done, and only 81 schools are represented for indicators that rely on student-level data.

Instrument development and data collection

The interview guide and questionnaires used in this study were developed by an international team of researchers; they drew from multiple instruments that have been used to assess aspects of SRH education both in and out of school.1,2,29,32–37 Discussions were held with representatives from the Ministry of Education and various local organizations to gather necessary data or information that was used to refine the tools and make them country-specific.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the institutional review boards of the University of Cape Coast and the Guttmacher Institute. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Director-General of the Ghana Education Service. Following the selection of the regions and schools, letters were sent to the three regional directors of education, informing them about the survey and requesting their support. Two responded favorably to the request and in turn sent letters about the study to the selected schools in their respective regions. The regional director in Greater Accra did not respond to the letter, but the heads of schools in that region were shown the permission letter from the Director-General, which was sufficient to allow entry into their schools. Heads of all sampled schools were contacted by mail to solicit their support for and participation in the study; when necessary, follow-up contact was by phone and then by a visit from a member of the research team. Authorization from the school head was obtained before entering any school to field the surveys, and further authorization to survey students was obtained from each head; some heads solicited consent from school boards (where deemed necessary).

Informed consent was sought from all participants. To maintain students’ anonymity, neither heads nor teachers knew which students completed the survey. Students were made aware that their decision to participate was completely voluntary and that their responses were anonymous; they were given the possibility to withdraw from the survey at any time and to skip any question they did not wish to answer. Students who chose not to participate were instructed to remain in the room and work quietly on something else while the others completed the survey. All information provided by respondents was treated as strictly confidential, and access was denied to anyone outside of the research team. Key informant interviews were conducted in English, audio recorded (with their consent) and transcribed, and quotations have been anonymized.

Most fieldwork took place from February to April of 2015. Because of scheduling issues, for one school in the Greater Accra region, the survey was conducted in June 2015, and a few opinion leaders in the Northern and Greater Accra regions were interviewed in September of that year.

Data management and analysis

Qualitative data were examined using thematic and content analysis in NVivo. Quantitative data were double-entered into Excel 2013 and transferred into SPSS 22 and Stata 14 for analysis. Descriptive analyses were conducted by type of school (public or private) for each region. To ensure that all estimates were representative at the regional level, sample weights were applied to account for the different probabilities of a school, student, teacher or head being selected to participate. We provide the unweighted sample sizes in the tables.

We present regional-level data in tables at the end of the report, but in the text we present summary measures of the three regions combined. Figures are used to depict key findings, and all data provided in the figures also appear in the tables. We note specific differences between regions, and by school type and gender, only when those differences are statistically significant and have programmatic or policy relevance. We report differences by gender for measures related to students’ perceptions of school safety and out-of-school experiences with SRH education. All significance tests account for clustering at the student and teacher levels to ensure correct variance estimates. Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to detect differences in proportions and percentage distributions among regions, between public and private schools, and between females and males. When "other" response categories accounted for more than 5% of responses for a particular variable, these responses were analyzed and recoded into existing or new categories.

For some school-level indicators, especially those related to policies or program structure, we considered school heads’ responses to be representative of the entire school. However, for most school-level indicators, we relied on teachers’ and students’ responses, as they are more familiar with classroom practice. For questions asked of teachers, but presented at the school level, we classified a school response as "yes" if one or more teachers responded affirmatively; if one teacher in a school was teaching an aspect of SRH education, then we considered it offered in the school to some capacity. For questions asked of students and presented at the school level, we classified a school response as "yes" if at least 20% of students responded affirmatively to a particular question. We did not choose a higher cutoff because we wanted to ensure that a school was counted as offering a topic even if only a few students reported it, since only one of the grades surveyed may have covered it, or not all students may have taken that particular class. We required at least 20% of students because—while the average number of students per school in our sample was 36—some schools were very small and some indicators were based on a subsample of students. Capturing responses from at least 20% of students ensured that we were basing our estimates on the responses of more than one student per school in the very small schools.

In sections that present both teacher-level and student-level data, the teachers’ responses cannot be directly compared with those of students, even though in most cases we asked teachers and students similar questions. Topics related to sexual and reproductive health are included in different subjects and taught differently by multiple teachers, and we did not track which students were taught by which teachers. Rather, the teachers’ responses reveal the overall experience of teachers who cover the various topics, and the students’ perspectives show the overall experience with SRH education among the student body.

Throughout the report, we present students’ and teachers’ experiences as they occurred in schools during normal school hours. Students are also exposed to SRH information through a number of channels outside of the formal school setting, such as peer educators, media, parents and extracurricular activities (see Chapter 6). While such exposure can influence students’ attitudes and knowledge regarding SRH education, we do not expect it to influence their responses to school-based questions nor affect our assessment of classroom practice. Summaries of key findings are presented at the ends of Chapters 3–7.

Characteristics of samples

In the 82 sampled schools, we surveyed 78 school heads, 346 teachers and 2,990 students. Three-fourths of the schools were public, and most enrolled both females and males. A majority of the teachers in the study were male (61%), and seven in 10 had taught topics related to SRH education for three or more years. Of the sampled students, six in 10 were female, 80% were in Form 2, and the majority were aged 16 (35%) or 17 (56%). One–fourth of students (27% of males and 23% of females) had had sexual intercourse. For more details on characteristics of the survey respondents, see Table 2.2 for school heads, Table 2.3 for teachers and Table 2.4 for students.

CHAPTER 3: SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH EDUCATION IN GHANA

This chapter describes the policy environment driving sexual and reproductive health education in Ghana, the structure and organization of the program, the actors involved in curriculum development, and challenges to program development and curriculum design, and includes commentary on program comprehensiveness. This information is drawn from a desk review of policy documents and syllabi currently used in secondary schools in Ghana.

The legal and policy environment

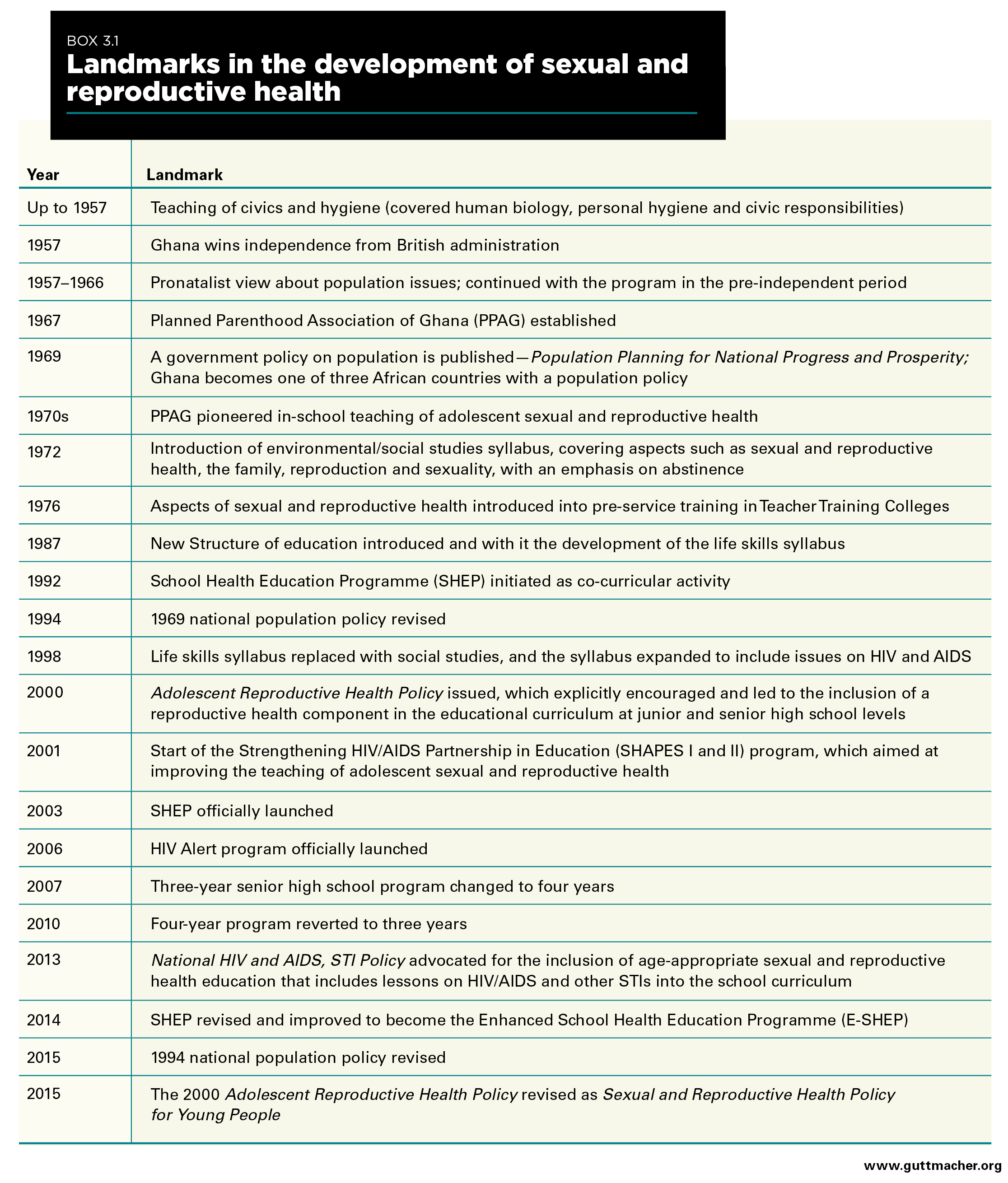

Curriculum-based sexual and reproductive health education has a long history in Ghana, and several policy and program developments have shaped its current provision (Box 3.1).38–44 At the national level, there is a legal framework as well as a supportive policy environment for the development and implementation of SRH education. However, while several policies and commitments address adolescents’ rights, and issues related to SRH, fewer directly address SRH education in schools. In 2000, the government published its first Adolescent Reproductive Health Policy (ARHP), which adopted a multisectoral approach to addressing adolescent reproductive health issues.45 The policy explicitly encouraged and led to the inclusion of a reproductive health component in the educational curriculum at the primary, junior high and senior high school levels. In 2013, the National HIV and AIDS, STI Policy advocated for the inclusion of age-appropriate SRH education in the school curriculum, which includes lessons on HIV/AIDS and other STIs.46

Ghana has agreed to several international declarations (e.g., the Abuja and Maputo Declarations) that have informed governmental decisions and actions on SRH, including specific changes relating to improving access to services and information for adolescents. The 2000 ARHP was revised in 2015 and renamed the Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy for Young People in Ghana.47 The vision for the new policy is "to have young people who are well informed about their sexual and reproductive health and rights, and are healthy."

Actors involved in curriculum development

The Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service, with support from the Ministry of Health, implement the School Health Education Programme in schools, which was developed in collaboration with a number of ministries and NGOs.§§ The development of national in-school curricula for the basic education system is the responsibility of the Curriculum Research and Development Division of the Ministry of Education. The Division works in consultation with various national and regional bodies—including the Ghana Health Service, the Ghana Education Service, the Ghana National Association of Teachers, the National Association of Graduate Teachers, the education units of religious bodies that administer schools, the National Youth Authority, traditional leaders, civil society organizations and various Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs)—to ensure the quality of the content developed, as well as to secure buy-in from necessary government entities and other key stakeholders.

Two groups that have significant influence at the local level are the Board of Governors and PTAs. The former constitutes the highest level of authority in the management of schools and consists of representatives from the community, teachers, the PTA, the owners or administrators of the school, past students, the Ghana Education Service and other members selected for their specific expertise. Although schools in Ghana operate with the same curriculum and syllabi, the Board, particularly in religious and private schools, influences the scope and topics to be taught and regulates co-curricular activities, including those regarding sexuality. The role of PTAs is to contribute to congenial school and academic environments, to foster effective teaching and learning, to provide resources (such as buses, classrooms and dormitory accommodation) in some schools and to support extracurricular activities. Through their activities and representation on the school Board, PTAs can influence the topics taught, especially in potentially controversial areas such as SRH education.

Curriculum content and structure

Although this study focuses on the senior high school level, the primary school and junior high school levels—where students are, on average, between 7 and 14 years old—are important entry points to begin addressing topics related to appropriate touching, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and gender equality.3 The exposure of students to SRH education in primary school is also advantageous given the high levels of enrollment in lower compared with upper levels. In the 2014–2015 academic year, 48% of 15–17-year-olds attended senior high school, while 85% of those aged 12–14 attended junior high school.48,49 This suggests that a comprehensive program introduced at the lower level may be even more impactful.

Sexual and reproductive health education, as defined in this study, is not explicitly included as a stand-alone, examinable subject in the Ghana national curriculum. Instead, the Ghana education system has adopted a cross-curricular approach, in which some topics related to SRH have been included in specified school subjects.50 Basic SRH education topics are introduced in the fourth year of primary school, a level at which all subjects, including those that cover SRH topics, are compulsory. In senior high school, however, the topics are integrated into two core, compulsory subjects (social studies and integrated science) and two elective subjects (biology and management in living). There are also two main co-curricular programs that offer additional activities outside of the regular curriculum, either during or after school: the School Health Education Programme (SHEP) and the HIV Alert program. Both programs operate in all schools in Ghana; they target students in primary and junior high schools in particular, but are also offered in senior high schools with support from the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Service.23,51 The cross-curricular and co-curricular approach makes it possible to spread the coverage of SRH topics across selected subjects, yet it precludes the opportunity to have a focused program that covers all aspects of a comprehensive SRH education program.

In-school SRH education at the senior high school level

For a complete list of topics included in the social studies, integrated science, biology and management in living curricula for senior high school, see the Appendix.42,52–54 Topics range from definitions and explanations of adolescence, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and biological changes in the body to gender relations and contributions of youth, but there is a strong emphasis on negative and irresponsible behaviors of adolescents, as well as a focus on the benefits of abstinence. While social studies includes a broad range of topics, those covered in integrated science and biology are more basic. The management in living curriculum addresses the most extensive list of SRH topics, including abortion (in the context of how illegal abortion affects adolescents), family planning, STIs and decision making. However, this subject is not compulsory; it is offered as part of the home economics elective program, which is generally attended by only a small group of students, and mainly females.

The number of academic units allocated to each of the subjects over the three senior high school years varies and is lowest for social studies (23 units) and highest for biology (75 units; Table 3.1). Although biology and integrated science are prominent in the curricula, they have the fewest units dedicated to SRH-related topics. Each lesson (i.e., coverage of a topic area) could span one or two periods, and each period typically lasts 30–35 minutes.

HIV Alert Program

The HIV Alert program was launched in 2006 as a co-curricular activity in primary, junior high and senior high schools and in Colleges of Education. Developed by the Ghana Education Service with support from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) for the in-school component and from UNFPA for the out-of-school arm, this program emphasizes the prevention of HIV infection and the importance of related issues, such as chastity and abstinence. The main target group for this program is 5–15-year-olds in primary and junior high schools. The program exists in Colleges of Education as part of the pre-service training for teachers who will cover this material at the primary and junior high school levels.

Enhanced School Health Education Programme

The School Health Education Programme, initiated in 1992 but officially launched in 2003, was established as a joint mandate of the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health; it aims to provide co-curricular health education, such as the HIV Alert program, to students in primary and junior high schools (aged 5–15). SHEP was established as one of the follow-up actions to Ghana’s commitment to the Jomtien World Declaration on Education for All and ratification of the United Nations Convention of the Rights for the Child. The goal of SHEP is to guide children in school to acquire the knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to achieve lifelong health.23 Specific objectives include providing effective school health education, ensuring safe and healthy learning environments, providing health services and using schools as an entry point to implement health policies.

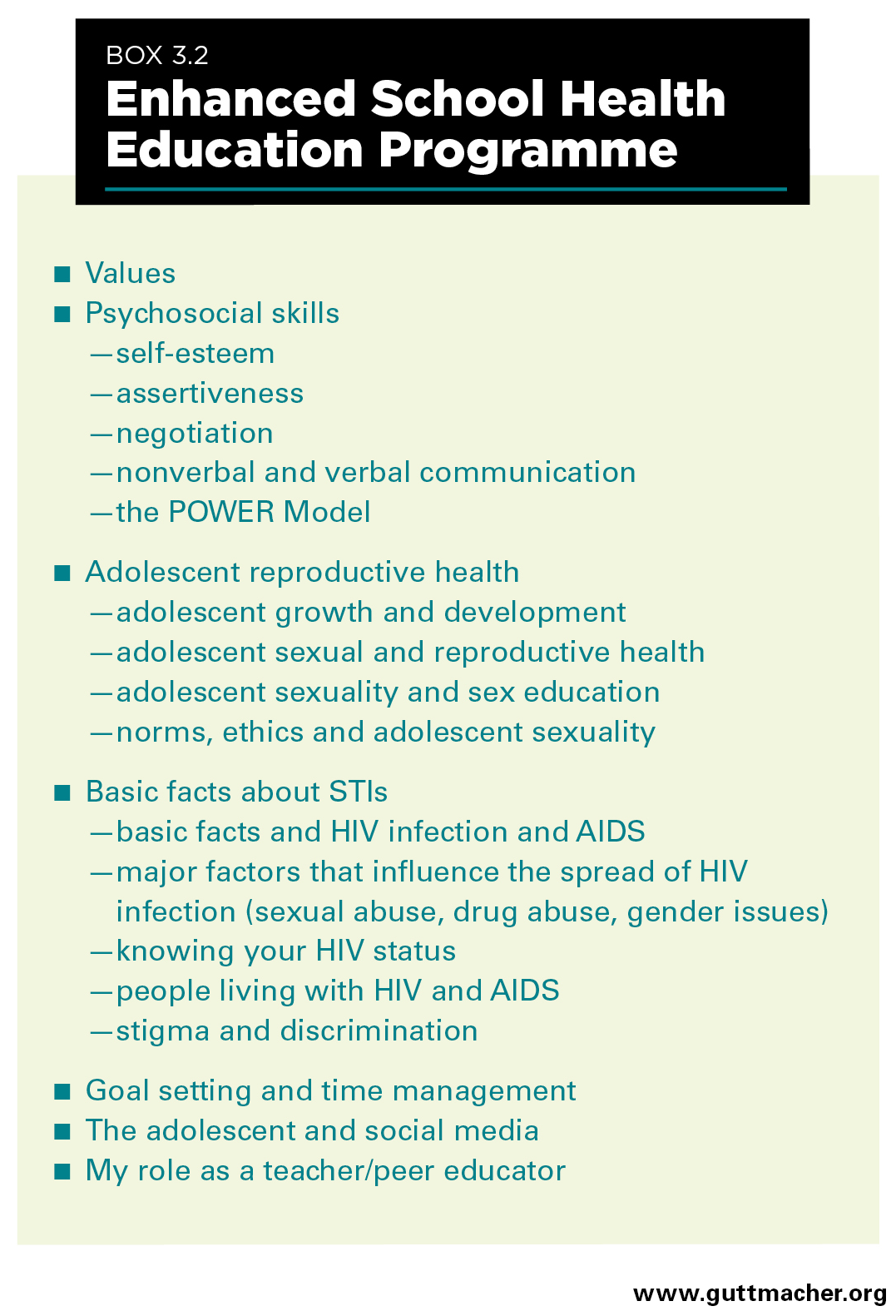

With support from UNICEF, UNFPA and the United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), SHEP was revised and expanded in 2014 and renamed Enhanced SHEP (E-SHEP), with the subtitle Life Skills Based School Health Education.55 E-SHEP subsumed the HIV Alert curriculum and consists of four broad areas: values and psychosocial skills development; reproductive health, HIV and AIDS; issues of time management and goal setting; and the roles of teachers, peer educators and community members (Box 3.2). E-SHEP has a teacher-led component, in which some teachers are trained to provide co-curricular education, including counseling, in sexual and reproductive health in schools; a peer-led component, in which adolescents are trained to deliver information to their peers in schools and in communities; and a community-led component, which takes place in the community using trained community members.

Sexual and reproductive health education yes, but how comprehensive?

Current evidence suggests that participatory SRH education programs that include content on gender equality, power relations and human rights are more likely to be associated with positive SRH outcomes than are those that do not.15 According to the UNFPA definition of comprehensive sexuality education used in this study (see Chapter 2), CSE should "equip children and young people with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will enable them to develop a positive view of their sexuality," and practical skills, gender and rights are featured prominently.30 Research also shows that abstinence-only programs that do not acknowledge that adolescents may be sexually active are not effective in improving sexual and reproductive outcomes in adolescents.11,12

In Ghana, the integration of SRH topics into core and elective subjects, as well as co-curricular activities, has resulted in most junior high and senior high school students being exposed to basic SRH education concepts in school. However, a limited range of topics is covered as part of the compulsory school subjects. Topics such as communication and interpersonal skills, which are imperative for adolescent development, are included in the management in living elective curriculum and the HIV Alert module, and contraception topics are included in management in living and biology electives, but neither of these subjects is taken by all students. Other pertinent issues—such as negotiation skills, ability to manage risks, how to use and where to access contraceptives, gender and marriage, body autonomy, gender-based violence and gender equality—are not included in the compulsory social studies curriculum. Furthermore, issues involving young males are not given as much attention as those involving females. For instance, beyond the physical maturation of young males (semenarche), the challenges of male development and behavior (e.g., the societal macho image) are not addressed.

Another challenge to effective SRH education lies in the tone of the presentation. In Ghana schools, SRH information is often presented from a negative or reactive perspective. Indeed, the introduction to the adolescent reproductive health section in the social studies curriculum states:42

"As adolescents mature and become sexually active, they face serious health risks. Many adolescents face these risks with too little factual information, too little guidance about sexual responsibility and too little access to health care. There is consequently a rampant wave of the following: (1) adolescent pregnancies, (2) adolescent denial of paternity of pregnancies, (3) child abandonment and (4) irresponsible sexual relationships."

The curriculum adopts a fear-based perspective when discussing challenges that adolescents face rather than emphasize their unique opportunities and needs at this stage. The emphases in the SRH-related topics are directed at problematizing sexual behaviors among adolescents; premarital sex is described as one of many irresponsible behaviors and as being the cause of negative health and social outcomes. The same approach is used in the management in living curriculum, which covers a broad range of topics but still casts a negative light on some topics related to adolescent sexual behavior (see Appendix). The teaching of issues related to human rights is focused on the perpetration of human rights abuses, rather than on a respect for human rights. Throughout the syllabi, the negative consequences of actions dominate the presentation of topics.

Moreover, the SRH-related components in the various curricula focus heavily on the importance of abstinence and the dangers of sexual activity, and pay little attention to healthy sexual behaviors, such as negotiation skills and contraceptive and condom use, which adolescents will need to know about in the future. The argument has been that this approach is in line with the beliefs and expectations of Ghana society, and therefore this approach reflects what adolescents need. However, this argument ignores the fact that some adolescents do engage in sex outside of marriage for whatever reason, and need to be supported with the necessary information and resources to enable them to protect themselves and make healthy decisions.

One key informant—a government official from the Greater Accra region—argued for the importance of maintaining the current content of the curricula within the norms of traditional society "because as a society we are very religious, we believe in morals and so we want the young ones to know what the values of society are." However, other informants expressed the importance of enhancing SRH content, and of including relevant topics that adolescents face. Some proposed that topics should be added to the SRH education syllabus and that these should be included in the core curriculum rather than as electives:

"I think they are all relevant [topics]. Actually, we have gone further to develop a manual for school on adolescent reproductive health, and it has a few more topics than that. We have something on drugs, and the other issues that are pertinent to the adolescents, and more on values and assertiveness.... We are trying to give [adolescents] an enhanced school health education that looks at all the issues that they face."

—Government official, Greater Accra region

"I think these topics are very brilliant, but one that you have in the elective, but not in the core subject, is decision making. I think it’s quite critical that we [include] it as one of the core topics."

—Respondent from an NGO

Summary of findings

- Ghana has a supportive policy environment for SRH education. The Adolescent Reproductive Health Policy, revised in 2015, led to the inclusion of a reproductive health component in the curriculum in junior high and senior high schools.

- In 2013, the National HIV and AIDS, STI Policy advocated for the inclusion of age-appropriate SRH education (including HIV and other STIs) in the school curriculum.

- National basic education curricula are developed by the Curriculum Research and Development Division in consultation with government bodies, teachers’ associations, religious groups, youth associations, traditional leaders and civil society organizations; at the school level, the Board of Governors and Parent-Teacher Associations can also influence the topics that are taught.

- SRH education is not a stand-alone subject in the national curriculum. Topics are integrated into different subjects, some of which are core (compulsory) and others elective; topics in elective subjects tend to be more comprehensive.

- SRH education is taught from primary 4 through senior high school. Primary school is an ideal entry point for comprehensive SRH education, given the high level of school enrollment and the compulsory nature of all subjects at that level, coupled with the fact that some young adolescents are already engaging in sexual activity and need accurate and age-appropriate information to stay healthy.

- Curricula focus heavily on the promotion of abstinence and exclude coverage of healthy sexual behaviors. Information is often presented from a negative perspective by emphasizing challenges that young people face rather than opportunities, and problematizing sexual behaviors among young people. The teaching regarding human rights is focused on the perpetration of human rights abuses, rather than on respect for human rights.

- There are two co-curricular programs for students in primary, junior high and senior high schools. The Enhanced School Health Education Programme provides health education through teacher-led, peer-led and community-led components, ensures safe and healthy learning environments, and provides health services. The HIV Alert program specifically emphasizes HIV prevention.

- While the integration of SRH topics into multiple subjects and co-curricular activities means that most students are exposed to basic SRH concepts in school, the range of topics covered as part of the core curricula is limited, as many key topics—such as negotiation skills, accessing and using contraceptives, gender-based violence and human rights—are covered only in elective subjects or co-curricular activities.

CHAPTER 4: SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH EDUCATION IN THE CLASSROOM

Several aspects of sexual and reproductive health education contribute to its effectiveness, including its placement in the curriculum, pedagogical approach, timing and quality of delivery, and the comprehensiveness of the skills and information it imparts.3 This chapter presents findings on the implementation of SRH education in schools, relying on the surveys with school heads, teachers and students to describe the organization of the program, the timing and format of teaching, curriculum content, teaching methods, student preferences, class environment, and monitoring and evaluation systems in place.

Organization, timing and format

While all surveyed schools teach topics related to SRH education as part of the national curriculum, 43% also cover these topics as a co-curricular activity (Table 4.1). Some school heads reported that their SRH education program had no supporting group (34%) or was independently run by the school (29%), but nearly one-third (30%) said the program was taught under SHEP and one-fifth (19%) cited the HIV Alert program. Most schools, according to students, had various outside individuals come in to teach topics related to SRH education, such as health providers (91% of schools), religious persons (77%) and peer educators (64%). These individuals were more likely to teach SRH in public schools than in private schools, especially peer educators (87% vs. 39%). Health personnel from the Ghana Health Service are important in the teaching of SRH education, and are permitted to provide counseling but not clinical services for contraceptives on school premises (personal communication with the Ghana Health Service, the Ghana Education Service and NGOs, 2015).

According to the national syllabus, the time allocation for teaching social studies, which includes topics related to SRH education, is three periods per week (see Table 3.1), which translates to 16–21 hours per term.*** According to reports from teachers, fewer than a third of schools designate more than 10 hours to SRH education in Form 2 (31%), and only one-fourth dedicate this much in Form 3 (Figure 4.1).††† The regional variation in the reported allocation in Form 3 could be attributed to the approach of individual schools or teachers rather than to the national standards set in the curriculum. Among students in coeducational schools who had been exposed to SRH education, 86% reported that all topics were taught to males and females together, 12% reported that some were taught together and some separately, and 3% said all were taught separately (Table 4.2). A higher proportion of males than of females preferred to have all topics taught together (85% vs. 76%).

As described earlier, SRH topics are integrated into school subjects, and some are introduced in primary school, where all subjects, including those that cover SRH topics, are compulsory. Across the study regions, more than three-fourths of students had been exposed to SRH education by the time they completed Class 6, the end of primary school. Most of the remaining students were first exposed to SRH education during junior high school, and 97% of all students reported some exposure prior to starting senior high school. One-fourth of the sampled students (mostly aged 15–17) had already had sexual intercourse—27% of males and 23% of females at the time of the survey; the findings suggest that many had likely received some SRH education in school or from HIV Alert or SHEP prior to initiating sexual activity. However, among those who were introduced to SRH education topics in either primary or junior high school, about half (48–50%) would have liked to have started learning even earlier; 44% were satisfied with the timing, and the remainder would have liked to have started later. As expected, most students (95%) learned about SRH as part of social studies, followed by integrated science (72%)—both being core subjects at the junior high and senior high school levels (Figure 4.2).

Content of curricula

Topics offered

Teacher perspectives. According to teachers, schools teach most topics related to SRH education (Table 4.3).‡‡‡ The topics that were the least commonly taught were where to obtain contraceptive methods (84%), communicating within relationships (88%) and decision-making skills (92%), and each was more likely to be taught in public than in private schools (98% vs. 68%, 99% vs. 76% and 99% vs. 84%, respectively). Public schools were also more likely than private ones to cover all topics in the values and interpersonal skills and contraception and unintended pregnancy categories.

On the basis of our methodology described in Chapter 2, the comprehensiveness of the range of topics taught was deemed at least "minimum" from the teachers’ perspectives in 99% of schools, at least "adequate" in 89% of schools and "high" in 83% of schools (Figure 4.3). Private schools were less likely than public ones to score a "high" level of comprehensiveness (68% vs. 96%).

Student perspectives. While we cannot directly compare student and teacher responses, student perspectives on SRH education topics taught in their classes tell a slightly different story. The topics that students reported most commonly learning about were puberty and physical changes, reproductive organs, abstinence and HIV/AIDS (92–97%; Table 4.4; Figure 4.4). Students also commonly reported learning about sexual and reproductive rights (87%), menstruation (87%), pregnancy and childbirth (81%), STIs other than HIV (74%), prevention of violence and sexual abuse (71%), and abortion (66%). Nearly half said they learned about contraceptive methods (49%), where to get HIV/STI services (47%), equality between men and women (47%) and communicating within relationships (45%); somewhat fewer learned how to use methods (40%) and where to get them (36%). Regardless of region or school type, most students (62–71%) who had learned about a particular topic wanted to learn more, implying that the extent to which topics are currently taught is inadequate (Table 4.5). The five topics with the largest gap between the proportion of students who learned about the topic and those who wanted to learn more are presented in Figure 4.5.

Most students (72%) reported learning about all topics in the category of sexual and reproductive physiology, but far fewer learned about all topics in HIV and STI prevention (40%), gender and SRH rights (27%), contraception and unintended pregnancy (24%), and values and interpersonal skills (19%; Figure 4.6).

According to students’ reports, the comprehensiveness of the range of topics covered appeared to meet at least the "minimum" for 74%; it was at least "adequate" for 19% of students and "high" for only 8% (Figure 4.7). While teacher and student responses are not directly comparable because we do not know which teachers taught which students, or in what grades teachers were teaching particular topics, it is nonetheless notable that the comprehensiveness of topics covered from the student perspective was much lower than the level reported by teachers. Some students may underreport what they have learned in an effort to make the case for needing more SRH education, yet it is equally likely that they might overreport topics covered in an effort to impress the fieldworkers or prove that they have been attending class and paying attention. These two potential biases would cancel each other out. Teachers, on the other hand, may have an incentive to overreport the number of topics they are teaching if they believe these topics are part of the curriculum and that they should be taught. Although the greater comprehensiveness reported by teachers may be partly due to teachers covering some topics in grades that students have not yet reached, this is unlikely to explain the large discrepancy.

Concepts and messages conveyed

Teacher perspectives. The information provided by teachers confirmed that the messages most of them delivered on SRH education were focused on abstinence, and this approach set the tone for what students were learning (Table 4.6). Most teachers reported very strongly emphasizing that young people should avoid having sex before marriage (85%) and that having sexual relationships is dangerous (83%) or immoral (81%) for young people. Overall, 56% of teachers very strongly conveyed to students that they should protect themselves during sex by using condoms, and this emphasis varied by region: 75% in the Northern region, 64% in Brong Ahafo and 42% in Greater Accra. Teachers across the regions reported very strongly emphasizing that homosexuality is unnatural (68%) and that abortion is immoral (78%). Nonetheless, 78% reported very strongly conveying that young people have the right to know everything about relationships and sexual and reproductive health.

Nearly all teachers said they covered contraceptive methods (97%) and abstinence (96%) in their SRH education classes. Virtually all (99%) taught about condoms, and most covered the rhythm or calendar method (87%) and the pill (83%; Table 4.7; Figure 4.8).

While most teachers reported covering contraceptives, the quality of the information provided varied. A number of messages related to the effectiveness of contraceptives in preventing infection with STIs or HIV and avoiding pregnancy were conveyed. Notably, 24% of teachers who taught about contraceptives emphasized in their classes that they are not effective in preventing pregnancy (Figure 4.9). The proportions of teachers reporting this message varied by region, from 14% in Brong Ahafo and 17% in Northern to 33% in Greater Accra. Nearly nine out of 10 teachers (86%) who taught about condoms emphasized that condoms alone are not effective in pregnancy prevention, and a third taught that condoms are not an effective means of STI/HIV prevention (34%; Figures 4.10 and 4.11). Teachers in Greater Accra were more likely to convey this message (43%) than were those in the Brong Ahafo (25%) or Northern (26%) regions. Among teachers who covered abstinence, 82% emphasized that it was the best or only method for preventing STI/HIV infection and pregnancy (Figure 4.12).

Student perspectives. Encouragingly, most students indicated that they had learned about the signs and symptoms of STIs and HIV (89%), ways to prevent HIV (91%) and pregnancy (87%), and respect for self and others regardless of gender or social status (87%; Table 4.8). While a major aim of SRH education is to impart the practical skills and knowledge needed for adolescents to navigate their sexual and reproductive lives, only a third to half of students reported being taught practical skills such as how to talk to a partner about getting tested for HIV (49%), how to recognize forced sexual contact (40%), what to do when one becomes pregnant or gets someone pregnant (36%), or how to communicate with a partner about contraceptive use (46%). There were significant regional variations in students’ exposure to these fundamental lessons.

Comprehensive SRH education programs recognize that adolescents can be sexually active, and seek to teach them how to exercise their sexual and reproductive rights safely and responsibly. Generally, however, teachers’ reports of using reactive approaches as proposed in the syllabus appeared to be corroborated by students. Three out of every four students reported that the content of their SRH education very strongly conveyed the message that having sex is dangerous for young people (72%) and that sex should be delayed until after marriage (75%). Sixty-eight percent said they heard a very strong message that it was best to avoid sex, but if they did engage in sex, they should use condoms. For all of these messages, significant student reporting differences were seen across regions, and for the last message, a difference was also observed between students attending public versus private schools.

Teaching methods

The use of less didactic teaching methods that involve students as active participants—such as group learning, peer engagement and learner-centered methodologies that aim to build students’ values and critical thinking skills—is increasingly being recognized for the positive influence on learning and education broadly, suggesting that reliance on lectures alone may be insufficient to effectively impart knowledge in a classroom. All teachers interviewed indicated that they used lectures or talks to teach topics in SRH education; many also reported using assignments (97%) and quizzes (81%) in their classrooms (Table 4.9). Three-fourths of teachers employed charts or drawings, and 60% reported using creative, participatory learning activities, such as role playing, theater, debates, art projects, dance, poetry and storytelling, while 39% reported practical demonstrations (e.g., how to use a condom). Notably, 81% of students said they wanted teachers to use creative, participatory learning activities in their classes (Table 4.10).

Forty-four percent of the teachers who cover contraceptive methods physically showed methods to students so they could see how they work (Table 4.11). Four out of 10 reported showing students the proper way to use a condom via printed materials or film, or physically demonstrated the proper way to use one. Linking information to sexual and reproductive health services outside of the classroom is an essential component of a comprehensive SRH education program; 69% of teachers gave information about where students could obtain contraceptive methods or counseling, and this guidance was more commonly reported by teachers in public than in private schools (73% vs. 54%).

Class environment

The success of a curriculum in promoting student learning can be greatly impacted by the classroom environment.56 Teachers face a multitude of challenges when teaching topics related to SRH education. The most common problems reported across the surveyed regions were related to logistics: Seventy-seven percent of teachers reported a lack of resources or teaching materials, and 49% reported a lack of time to teach SRH topics; smaller proportions cited moral or religious contradictions, embarrassment, or opposition from the community or students (Table 4.12; Figure 4.13).

Students’ perceptions of the class environment during SRH education varied. Eighty-two percent who had learned about SRH topics expressed excitement about studying the issues, yet half said the classes were too crowded and 40% said students were embarrassed to talk about the topics. Perceptions of teachers’ authority and competence can also play a role in students’ learning experience. One-fifth had the impression that their teacher was embarrassed to talk about SRH topics, and one-tenth perceived that their teacher did not know enough about the topics (Figure 4.14).

For an SRH education program to achieve its intended goals, an open, frank and warm environment is required.57 Adolescence is a transitional time during which many questions about the body, sexuality, relationships and a range of other SRH topics will be raised. Students need the freedom to express doubts and ask questions about these issues in order to absorb and connect with what they are learning.58 However, students may face challenges in the classroom: Overall, only 27% stated that they felt they had always been able to ask SRH-related questions in classes. Among those who reported that they had wanted to ask at least one SRH question in class but had not, 41% cited embarrassment as the reason. One-third cited time constraints or worry that they would embarrass or offend someone, or feared the teacher or other students would shut them down. Reports of the obstacles cited by students varied by region.

Monitoring and evaluation

Because there is no stand-alone SRH education program in Ghana, there is no clear standardized mechanism for monitoring or evaluating its teaching on a national level. Rather, any oversight of the SRH education topics is done under the monitoring or evaluation of the subject in which the topics are integrated. Our survey of schools assessed whether teachers were evaluated for their teaching of SRH education at the school level (e.g., by school administrations or heads), despite the lack of a national-level monitoring system. Heads of schools are expected to be the frontline personnel for educator assessments, and more than half (53%) said they assessed their teachers several times a term, while nearly a third (30%) admitted that they had never evaluated their teachers regarding SRH topics (Table 4.13). School heads who had evaluated their teachers reported doing so through classroom observation (85%), oral assessment (56%) or written assessment (37%). Only 14% of heads used student feedback or inspected teachers’ lesson plans as a means of assessment.

According to teachers, students are more commonly assessed on their knowledge (in 100% of schools) than on attitudes (88%) or practical or life skills (83%). Public schools were more likely than private ones to assess students’ practical or life skills and attitudes regarding sexual and reproductive health. Student evaluation on practical or life skills also varied by region, from 59% in Brong Ahafo to 95–100% in the Northern and Greater Accra regions.

Summary of findings

- SRH education is taught in all schools as part of the national curriculum, and as a co-curricular activity in 43% of schools. Health providers, religious persons and peer educators commonly come into schools to teach SRH education topics.

- Nearly all students had received some SRH education by the time they completed junior high school (97%), and nearly half of students would have liked to have started earlier than they did.

- While 83% of teachers claimed to teach all topics that constitute a comprehensive SRH education, only 8% of students reported learning about all of them.

- Nearly all students had learned about topics related to physiology, abstinence and HIV; the majority also commonly reported learning about sexual and reproductive rights, STIs other than HIV, prevention of violence and sexual abuse, and abortion. However, fewer than half of students had learned about contraceptive methods or practical skills, such as where to access HIV/STI services, communicating in relationships, how to use contraceptives and where to get them.

- Teachers and students both agreed that messages conveyed by teachers tended to be reactive and focused primarily on abstinence, with an emphasis that sexual relationships are dangerous and immoral for young people and should be delayed until after marriage.

- While nearly all teachers reported covering contraceptives, the nature of the information varied, with most teachers emphasizing that condoms are not effective in preventing pregnancy (86%). Some also taught that condoms are not effective for STI/HIV prevention (34%), and that contraceptives are not effective in preventing pregnancy (24%).

- Among teachers who cover contraceptive methods, about four in 10 show students the methods, and seven in 10 provide information on where to obtain contraceptive services.

- All teachers used lectures and talks to teach SRH topics; more than half used creative, participatory learning activities, and fewer used practical demonstrations; 81% of students said they would like to engage in more of these types of approaches.

- The main challenges reported by teachers were lack of resources or teaching materials and lack of time; fewer reported moral or religious contradictions, embarrassment, or opposition from the community or students.

- While students expressed excitement about SRH education, many had been unable to ask a question in an SRH education class because of embarrassment, time constraints, worry that they would embarrass or offend someone, or fear that the teacher or other students would shut them down.

- Since SRH topics are integrated into examinable subjects, coverage of the syllabus implies coverage of these topics. However, there are currently no tools to specifically monitor or evaluate the teaching of SRH education.

- Students are more commonly assessed on SRH knowledge than on attitudes or practical skills.

CHAPTER 5: SCHOOL SYSTEM SUPPORT FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH EDUCATION

Improving the content of curricula, ensuring that teaching methods are adequate and conducive to learning, and establishing monitoring systems to ensure quality are essential to improving sexual and reproductive health education in schools, but the quality of the teaching ultimately depends on the preparedness, confidence, knowledge and skills of teachers. Adequate training in the content, teaching methods and approach to SRH topics is essential for teachers. An enabling and safe school environment has also been identified as a key component to a successful SRH education program.30 This chapter presents quantitative and qualitative findings on these issues.

Teacher training

All teachers in Ghana, regardless of subject or level, are required to undergo pre-service training. SRH topics are included to a certain extent in pre-service and in-service training, but as mentioned earlier, there is not training designed specifically to prepare teachers to cover these topics. According to our survey of school heads, 78% of schools require that teachers receive pre-service training before teaching SRH topics, but in-service training is required in only 16% of schools. About one-fifth of schools (21%) do not require any specific training for teachers to cover such topics, since those teachers would have received some training in their own disciplines (not shown). Among the teachers surveyed, 78% had received pre-service training in an SRH education‒related subject (Table 5.1; Figure 5.1). Only 39% of teachers had received any in-service training on the topics, with just 14% having received such training within the past three years (Figure 5.2).

Eighty-four percent of teachers who had received either pre-service or in-service SRH education training reported that the training covered at least one topic in each of the five thematic SRH categories (a "minimum" level of comprehensiveness in the range of topics covered). Fifty-five percent had received training on nearly all topics in each category (an "adequate" level), and 40% had received some training in all topics (a "high" level; Table 5.2). Half of teachers who received either pre-service or in-service training reported that they had not received any training in teaching methods, despite most training institutions having adopted the concurrent approach whereby teachers are supposed to be exposed to both the content and teaching methodologies at the same time. Eighty percent of teachers who received pre-service training said they would benefit from a separate pre-service training specifically for SRH education, and between 80% and 94% of teachers who received any training wanted more hours of training in general and more training on certain topics.

Some key informants indicated that teachers who are expected to cover these topics may be inadequately and unevenly prepared. The two major universities devoted to the pre-service training of senior high school teachers—the University of Cape Coast and the University of Education, Winneba—approach the training of SRH education teachers differently. For example, teachers-in-training at the former university are trained in individual subjects chosen by the teachers themselves (e.g., geography, economics, biology, physics). While the training is comprehensive within each subject, it is feasible that a teacher would graduate fully prepared to teach geography, for example, but then be asked to teach social studies once employed at a senior high school and not be adequately prepared. The University of Education, however, has a specific program dedicated to social studies and has adopted the integrated approach as employed in the junior and senior high school curricula. These two approaches have implications for teachers’ level of preparation for teaching SRH topics.43 As pointed out by one respondent:

"Well, at times some of us who are teaching in the classrooms have not been trained up to the university level to teach social studies. For instance, if you had studied geography, economics or government, it is felt that you can easily handle social studies.… So you have to read and tell [students] what you have read."

—Teacher and PTA member, Brong Ahafo region

In recognition of this situation, the Ministry of Education and the Ghana Education Service have been organizing in-service training programs for teachers on SRH topics, such as the 2001 USAID-supported Strengthening HIV/AIDS Partnership in Education (SHAPE I and II) program.59 However, there are also challenges with in-service training because of a lack of standardization across schools and sustainability issues as a result of inadequate funding. One policymaker commented on the implementation of in-service training:

"We do in-service training for those who are teaching. But this [occurs] in bits and pieces. It is done when funds are available…. We have trained 9,868 teachers from 14 districts as part of in-service. We are also training teachers in the districts in the Brong Ahafo region. The aim is to train the teachers on how to acquire knowledge and skills to enable them to teach."

—Policymaker, national level

Currently, Colleges of Education—where teachers are trained for the junior high school level—offer a stand-alone subject on HIV education that is based on the HIV Alert program. Teachers attending such colleges receive concentrated training on topics related to HIV and AIDS, but receive little training on other essential SRH topics.

Teaching support

Support and resources available to teachers

The logistical and moral support that teachers receive is vital for the overall quality of teaching and learning. Most teachers reported having access to materials describing the scope and sequence of instruction, as well as the goals, objectives and expected outcomes of SRH education (89‒94%; Table 5.3). Sixty-eight percent of teachers received support from their colleagues, while nearly half (49%) turned to internet resources, including social media, to assist them in teaching SRH topics. Ninety-two percent of school heads said they supported teachers covering SRH in some way, including by organizing meetings with them to discuss or resolve issues (61%), inviting teachers to talk to them separately about concerns (58%) and voicing support at board, PTA or community meetings (46%).

However, teachers said they wanted additional assistance in various forms to help them teach more effectively (Table 5.4); the most commonly cited needs were for more teaching materials and strategies (79%) and more factual information and training (44‒45%; Figure 5.3). Teachers also requested more assistance in different topics (Table 5.5), the most-cited being contraceptive methods, use of methods and HIV/AIDS (Figure 5.4).

Teachers’ perceptions of support

In teaching SRH education, support from authority figures and other stakeholders is important.60 While most teachers perceived their school heads and other teachers to be supportive or very supportive of their teaching SRH topics (90% and 94%, respectively; Figure 5.5 and 5.6), nearly one-third (31%) perceived parents to be unsupportive (Figure 5.7). Very few teachers, however, felt outside pressure that negatively affected their teaching of SRH topics (not shown).

School environment

The school environment provides the framework within which teaching and learning occur. In Ghana, SRH issues are rarely discussed in public, and so it is important that a safe environment, free of fear and intimidation, is created in schools so that young people can discuss these important matters in the classroom. Despite the existence of national regulations that protect the rights of children and youth within schools,61,62 only slightly more than half (52%) of school heads indicated that their schools had child protection policies (Table 5.6).

The Ghana Education Service has an explicit code of ethics for teachers,63 which protects students by prescribing expected behaviors and the sanctions for flouting them. Yet 12% of school heads reported that their schools did not have a specific policy to address sexual harassment of a student by a teacher. Ten percent indicated that they had no policy on sexual harassment between students. Among schools that did carry out disciplinary action for harassment, most followed a process of giving several warnings, followed by suspension and potentially expulsion or termination if the case was proven. This creates a potentially unsafe environment, especially for females, because sexual harassment in school has been well noted as a major barrier to education. Another barrier for female students is dropout as a result of getting pregnant.64 The Ghana Education Service’s policy is that individuals who become pregnant should be allowed back into the same school following childbirth.65 However, this policy may not do enough to support those who become pregnant, as it does not provide sufficient support for female students during their pregnancy. Only 26% of schools (mixed gender and females only) would allow someone who became pregnant to continue her studies, while 57% of schools would ask her to stay home until she gave birth, and 17% would require her to transfer or would expel her. The general practice, because of stigma and embarrassment, is for her to be assisted in transferring to a different school following childbirth.