It has been more than six years since Congress passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and more than two years since the most substantial components of that law took effect, including the major Medicaid expansion, the new private insurance marketplaces and affordability subsidies, and the so-called individual mandate that requires most Americans to either have comprehensive health insurance or pay a tax penalty. Despite ongoing political attacks and multiple Supreme Court challenges, the ACA has cemented itself into the foundation of the U.S. health care system.

Although many conservatives are still focused on repealing the ACA, other state policymakers of all political stripes are hoping to tailor it to better fit their ideological preferences, local politics and the needs of their residents. And, indeed, Congress designed the ACA to provide states with much of the flexibility that state policymakers crave. States have long had the option of seeking changes to their Medicaid program through "waivers" of federal law, and several states have used this process to implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in a manner that better fits their conservative principles. Another source of flexibility for states is coming online in 2017: ACA innovation waivers—authorized under Section 1332 of the ACA—will allow states to revisit the main pillars of the law’s private insurance expansion.

Yet, although states have some flexibility, federal law sets limits on how far they can adapt Medicaid or the ACA’s private insurance reforms. The Obama administration—in keeping with federal statute and congressional intent—has upheld robust protections for enrollees’ coverage and access to high-quality, affordable care, including sexual and reproductive health care. The next administration has the opportunity to weaken these protections in ways that might undermine access to sexual and reproductive health care and providers. Alternatively, the next administration could help states further advance access to comprehensive coverage and care, including sexual and reproductive health care.

Medicaid Waivers

The concept of states seeking waivers from federal law should be familiar to longtime observers of Medicaid. Section 1115 of the Social Security Act allows the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to waive numerous federal Medicaid requirements, to let states test out new approaches to health care coverage and delivery that promote Medicaid’s objectives of delivering affordable care to low-income and vulnerable populations. States have had that option since the advent of the Medicaid program in 1965 and have been increasingly aggressive in their pursuit of Medicaid waivers since the 1990s. Today, the majority of states are operating at least one Medicaid waiver under Section 1115.1 (States have additional waiver options under other sections of federal law, but Section 1115 provides the broadest range of possibilities for states.)

Waiver programs are the product of often intensive negotiations over the course of months or even years between state governments and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Waivers are typically approved for an initial five-year period, after which they must be renewed periodically.2 States are required to evaluate the impact of their changes to Medicaid, in line with the idea that they are meant to be research and demonstration programs. Moreover, states must demonstrate that the waiver is budget neutral for the federal government—meaning that the federal government reimburses the state no more than it would have in the absence of the waiver.

States have used the Medicaid waiver process to implement a wide variety of changes to their Medicaid programs, including requirements related to eligibility and enrollment, benefits and cost-sharing, and provider networks and payment. States have made sweeping state-wide changes, conducted regional experiments and expanded coverage for narrow sets of services. In the field of sexual and reproductive health, Medicaid waivers are perhaps best known as the original means by which states have expanded eligibility for family planning coverage to women and men ineligible for broader Medicaid.3

States can, in theory, request waivers for a wide array of statutory provisions that lay out the essential rules for state Medicaid programs and for federal Medicaid payments to the states. However, CMS gauges waiver applications according to whether they will meet core Medicaid objectives, including whether a waiver will improve coverage for low-income state residents, the network of available providers, the efficiency and quality of care, and health outcomes.2 And the ACA stepped up another key protection for Medicaid waivers by setting new requirements for transparency and public input.

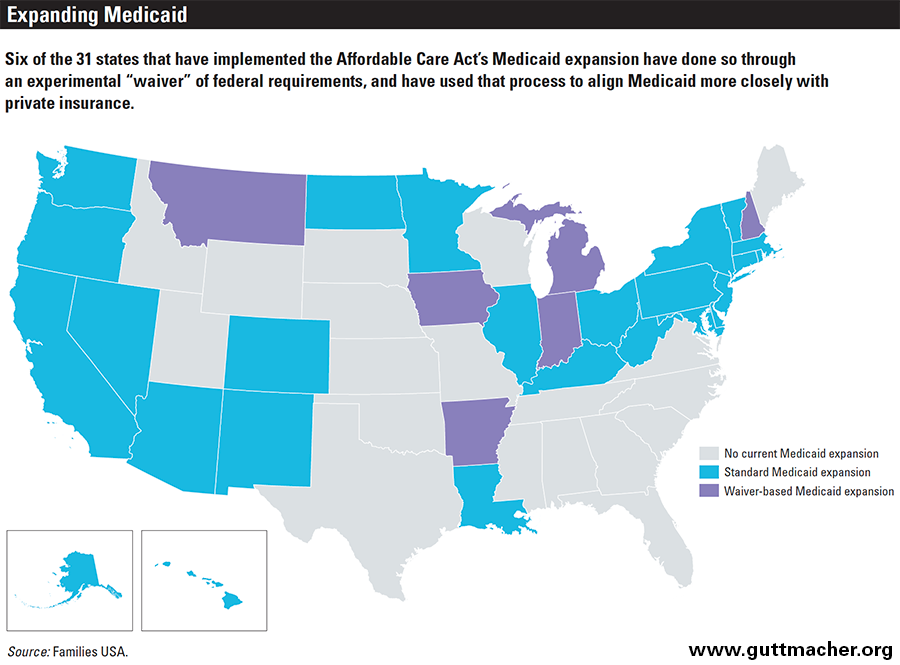

Although not new, Medicaid waivers have become increasingly prominent under the ACA, particularly in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, which effectively converted the ACA’s nationwide expansion of Medicaid to low-income Americans into an optional program for states. That decision gave states considerable new leverage in their negotiations with CMS. Conservative governors have demanded that the Obama administration allow them to make changes that they say will align their Medicaid programs more closely with private insurance, in exchange for expanding coverage; so far, six of the 31 states that have expanded Medicaid under the ACA have done so through a Medicaid waiver (see map).4

ACA Innovation Waivers

The ACA’s innovation waivers—which can be granted starting in 2017—are similar in many respects to Medicaid waivers. States will be required to gain approval from the federal government (in this case, from both DHHS and the Department of the Treasury) and will need to renew the waivers periodically (at most every five years).5 Also, they will need to gain input from the public, analyze the waiver’s potential impact on health coverage and government finances, evaluate the waiver’s impact once approved and follow numerous federal administrative requirements. Notably, the ACA requires states to pass legislation explicitly authorizing any waiver.

What states can do. Under the ACA innovation waivers, states will be able to amend how several major pillars of the health reform law work in their states.6 They may modify, eliminate or replace both the individual mandate and the so-called employer mandate (the requirement that large employers offer health insurance to their full-time employees or else face tax penalties). States may also modify all of the major aspects of the ACA’s private insurance marketplaces, including the structure of the marketplaces themselves, what counts as a health plan that qualifies for sale on those marketplaces, the eligibility and enrollment processes, the benefits that the plans must cover and the tax credits designed to help enrollees afford the plans’ premiums and cost-sharing. If a state modifies the affordability tax credits, the federal government will provide the state with the estimated total value of what state residents would have otherwise received, which will allow the state to use those dollars to make coverage affordable through other means.

What states cannot do. Notably, states will not be able to use ACA innovation waivers to alter other important provisions of the health reform law. For example, they may not undermine any of the ACA’s protections for private insurance more broadly, including the coverage requirement for preexisting conditions, the ban on lifetime and yearly coverage limits, the expansion of coverage for young adults on their parents’ health plans and the requirement to cover preventive services (including contraception) without patient out-of-pocket costs, among many others. Similarly, these innovation waivers may not be used to alter any aspects of Medicare, Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, although Section 1332 does require the federal government to set up a process for coordinating these ACA innovation waivers with the Medicaid waiver process and other similar options.

The health reform law sets additional limits—often described as "guardrails"—on what states can do under an ACA innovation waiver. States’ changes may not result in less comprehensive coverage, less affordable coverage or fewer residents with coverage, and they must be budget neutral for the federal government.

Federal guidance issued in December 2015 provided additional details about the four guardrails.7 Notably, in gauging how a state proposal will affect levels of coverage and whether that coverage is comprehensive and affordable, the federal government will look not only at the overall population, but also at specific groups—particularly, vulnerable groups such as those who are low-income or elderly, or those dealing with or at risk of developing serious health issues. In addition, in looking at whether coverage is at least as comprehensive as it would be in the absence of the waiver, states must look separately at each of the ACA’s 10 categories of essential health benefits. That means, for instance, that a state cannot bolster in-patient hospital care at the expense of preventive services, prescription drugs or maternity care.

In assessing a waiver’s potential impact on the federal budget, the federal government will use expansive definitions of federal revenue and spending—looking not only at direct changes (e.g., changes to the ACA’s affordability tax credits), but also indirect ones (e.g., any effects on income and payroll taxes, or new administrative costs for the Internal Revenue Service or the federally run marketplaces). This policy reflects the fact that the ACA plays a significant economic role in the United States, and that even slight adjustments could impact the federal budget substantially.

Moreover, the guidance makes it clear that states cannot use projected savings from changes within Medicaid—for example, changes that weaken coverage for Medicaid enrollees or make it more expensive for them—to help finance expanded private-sector coverage for higher-income groups via ACA innovation waivers. This clarification came in the form of details about how states might submit ACA innovation waivers that are coordinated with Medicaid waivers, as the health reform law explicitly permits. Specifically, the guidance asserts that the federal government will not take into account any changes or potential cost savings from a Medicaid waiver or any other waiver in assessing whether an ACA innovation waiver proposal is budget neutral.

Finally, the guidance put states on notice that the federal government is currently limited in its ability to help states implement their ACA innovation waivers. Specifically, the federal health insurance marketplace, HealthCare.gov, will not be able to set up different rules for different states. That means that states seeking to make substantial changes to the marketplaces—such as how people are assessed for eligibility or when they can sign up for coverage—will need to run their own marketplaces. Similarly, the Internal Revenue Service will not be able to administer state-specific rules about affordability tax credits or the individual and employer mandates, other than waiving a tax provision entirely. States would have to administer the provision on their own, such as through their own tax agencies.

Putting Waivers to Use

The ability to reshape health reform is an intriguing one for numerous

state policymakers from across the political spectrum.

The ability to reshape health reform is an intriguing one for numerous state policymakers from across the political spectrum. Progressives have talked about using Medicaid and ACA innovation waivers to achieve single-payer universal coverage in their state. Free-market conservatives have promoted the idea of dismantling Medicaid and even Medicare in their state, pushing everyone onto private-sector health insurance and greatly diminishing the role of government.

So far, Medicaid waivers have been the primary means through which states have been able to alter the parameters of the ACA, and the six states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Montana and New Hampshire) that have used the waiver process to implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion have generally done so in ways that move the program toward conservative ideals.8,9 (A seventh state, Pennsylvania, originally expanded via a waiver, but has since transitioned to a standard Medicaid expansion.)

For example, five of these states have adapted their Medicaid programs to promote private-sector insurance options through premium assistance programs for the Medicaid expansion population. These programs provide individuals with public dollars to help pay for employer-sponsored coverage or for plans offered on the state’s private insurance marketplace—an option sometimes referred to as the "private option." Premium assistance is designed to move Medicaid away from a program that directly provides low-income Americans with health coverage and toward one that instead helps them afford private insurance like what higher-income Americans purchase.

Conservatives have also used Medicaid waivers in a purported attempt to increase enrollees’ "skin in the game"—that is, increase their financial responsibility for their care, on the assumption that it will make them more price conscious and help drive down health care costs. Premiums and cost-sharing are central tools toward that end, and conservatives have often chafed at Medicaid’s limits on these tools. CMS has compromised with states on many such waiver requests, with each new waiver approval pushing long-standing boundaries of what states are permitted to do. States have been allowed to impose premiums and cost-sharing that go beyond what is permitted under Medicaid law, and to require enrollees to contribute to health savings accounts, which have long been championed in the private sector by conservatives. Several states have secured permission to disenroll some classes of enrollees who fail to pay their premiums and bar them from reenrolling for as long as six months. States have been allowed to use the carrot of reduced premiums and cost-sharing as incentives for specific types of healthy behavior, such as wellness exams and smoking cessation services.

CMS has drawn hard lines against other conservative priorities. So far, the agency has not approved requests to set limits on how long an individual can remain on Medicaid. It has denied state requests to require or incentivize Medicaid enrollees to work (although states can run voluntary work search and job training programs outside of Medicaid). CMS has not allowed states to eliminate the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment benefit, a long-standing requirement that ensures comprehensive coverage for enrollees younger than 21.

Of particular note for reproductive health, CMS denied requests by Iowa and Pennsylvania to waive Medicaid’s guarantees that enrollees have coverage for family planning services and the freedom to receive these family planning services from the qualified Medicaid provider of their choice, even if the enrollee is part of a health plan that otherwise restricts coverage to a specific network of health care providers. CMS has repeatedly acknowledged the importance of these protections for enrollees and for the family planning providers they rely upon. Most recently, in April 2016, CMS put states on notice that the freedom of choice provision prevents states from banning providers from Medicaid because they offer abortion services with non-Medicaid funds or are affiliated with an abortion provider.10

Starting in 2017, states will also have the new option of ACA innovation waivers. Yet, even as initially described in the ACA statute, the four guardrails of Section 1332 place real limits on how extensive a state’s health reform overhaul could be. It is difficult, for example, to expand coverage to more people without making that coverage less comprehensive, less affordable to enrollees or more expensive for the federal government—not without considerable new financial investment by a state itself. And the Obama administration’s 2015 guidance constrains states’ options further, such as by explicitly protecting vulnerable populations and by limiting states’ ability to combine ACA innovation waivers with Medicaid waivers.11,12

In the short run, states are looking at narrowly tailored changes through ACA innovation waivers. Hawaii, Massachusetts and Vermont have announced waiver applications so far, each focusing on coverage for small employers and looking to maintain state-specific reforms that predated the ACA. Other states, including California and Minnesota, are spending 2016 exploring their options—setting up task forces, meeting with stakeholders and the public, conducting studies and so forth. State policymakers are also learning from the third year of enrollment under the ACA’s Medicaid and private insurance expansions. More experience with how the "vanilla" version of the ACA works will help them as they consider further reforms.

In the long run, states may explore more sweeping options, assuming they can make them work under the statute and the administration’s interpretation of that statute. Notably, the next administration could change that guidance with little warning or public input, and may face considerable pressure from state officials and their allies to do so. Conservatives can be expected to continue their efforts to promote free-market ideology in Medicaid. By securing an ACA innovation waiver in addition to a Medicaid waiver, states might be able to coordinate their Medicaid and marketplace rules in ways that would make premium assistance and skin-in-the-game tactics more effective.

Progressive policymakers are exploring options of their own. For example, ACA innovation waivers could allow states to ease the law’s restrictions on immigrants’ access to affordable coverage—for example, by allowing undocumented immigrants to purchase coverage on the marketplaces, either with their own money or with state-financed subsidies. Lawmakers in California are currently exploring that option.13 States might also attempt to fix the ACA’s so-called family glitch, which has prevented many families from purchasing subsidized marketplace coverage because of a flawed definition of whether those families have an offer of affordable employer-sponsored insurance. That too would require state financial investment. States could also use ACA innovation waivers to set up a "public option": a publicly run health plan to compete with private plans on the marketplace, something that progressives fought for but failed to secure during the health reform debate.

Other reforms might appeal to a broader cross-section of policymakers and stakeholders. States could test out alternatives to the individual and employer mandates, which are highly unpopular but were deemed necessary by Congress and President Obama to make other aspects of the ACA work. States could also use waivers to better coordinate Medicaid, marketplace coverage and other insurance markets by standardizing key rules and definitions and by protecting enrollees against problems that come when they must transition from one type of coverage to another, such as having to change provider networks and facing steep drop-offs in affordability.

Remaining Vigilant

Reproductive health advocates and federal officials must

be on guard against attempts to use waivers to undermine sexual

and reproductive health.

All of the potential changes to health reform under Medicaid waivers and ACA innovation waivers have inherent consequences for sexual and reproductive health care and providers. How many people have coverage, whether that coverage is affordable and comprehensive, the breadth of provider networks and other types of change matter for sexual and reproductive health at least as much as they matter for any other type of health care.

Beyond that, in the event that conservative policymakers and activists ever come to terms with the idea that the ACA will not be repealed, reproductive health advocates and federal officials must also be on guard against attempts to use waivers to undermine sexual and reproductive health more directly. For example, conservative policymakers have taken aim at Planned Parenthood, by working in Congress and in the states to bar abortion providers and those affiliated with them from receiving public dollars, including reimbursement for services provided to Medicaid enrollees. CMS has made it clear that such attempts are illegal and has (as mentioned above) denied requests to waive that section of Medicaid law.10 There is no reason to believe that conservatives will stop trying, however, and they might also try to use ACA innovation waivers to extend those attacks to marketplace coverage.

In addition, advocates should be on the lookout for Medicaid and ACA innovation waivers that would restructure payment rules and network adequacy requirements in ways that could impact reproductive health providers. Advocates should continue their work to ensure that health plans must include safety-net family planning providers in their networks and reimburse them fairly. Notably, the ACA’s essential community providers provision—which requires marketplace plans to contract with safety-net providers, including family planning providers—could in theory be altered or eliminated under an ACA innovation wavier; however, doing so could undermine care for vulnerable populations, in direct violation of the statute’s guardrails.

Conservatives might also attempt to undermine coverage for sexual and reproductive health services in Medicaid and the marketplaces. The ACA’s preventive services guarantee—including its coverage protections for contraception, HIV and other STI screening, breastfeeding support and more—is not something that can be changed under an ACA innovation waiver. Nevertheless, reproductive health advocates should keep an eye on state attempts to expand formularies and other utilization control tools available to plans, to ensure that they do not somehow conflict with the coverage protections for contraception and other preventive services. Moreover, advocates should guard against attempts to limit other reproductive health services that do not qualify as guaranteed preventive care. (States already have authority to ban abortion coverage in Medicaid and the marketplaces, and federal dollars may not be spent on abortion, except in the most extreme circumstances.)

Looking Past the Elections

Under the Obama administration, it is difficult to imagine any of these types of direct assaults on sexual and reproductive health being approved under any sort of waiver. And the 2015 guidance on ACA innovation waivers staked out a clear position that the administration was not going to entertain sweeping changes to the marketplaces under the final year of its watch. Yet, that watch will soon be over. The 2016 elections will bring to power a new president, along with a new Congress and new players in many state governments. That may be the most important reason why most states are delaying any major work on ACA innovation waivers.

If conservatives sweep to power, the entire ACA may be in danger, and waivers may be entirely moot. But if federal authority falls to progressives or continues to be split, conservatives may see waivers as one of their best hopes for reshaping the ACA at least a little more to their liking. Similarly, under a progressive president but a mixed or hostile Congress, progressives at the state level may see waivers as their best chance to carry forward the goals of health reform. Either way, the potential consequences for sexual and reproductive health care could be profound, and those who advocate for that care will need to be aware and engaged in the process.