Conservative policymakers have long exploited the intersection of immigration policy and health care policy to undermine both. One notable result of these politics is the patchwork of federal restrictions on Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and the health care marketplaces established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that have barred access to health insurance coverage for many immigrants in the United States.

Recent Trump administration policies continue this tactic of restricting immigrants’ health care, while also using their health care needs as a pretext to restrict future immigration into the country. The administration appears to view health coverage for immigrants as a vulnerable target as it pursues broad–based anti–immigration, anti–health care and anti–reproductive rights agendas. The conservative philosophy behind these attacks is an exclusionary one that values people based on their current wealth, health and status, rather than their potential or their humanity. It views health care and other needs as privileges, not rights, and government support for these needs as a drain on society, rather than as an investment.

Progressive policymakers and advocates have fought the Trump administration’s policies in court and proposed legislation that would expand immigrants’ access to health insurance coverage and health care. These are steps toward a U.S. government and society that is pro-immigrant, pro–health care and pro–reproductive rights, and one that situates immigrants and their health care as vital parts of the American landscape. That version of the United States would value all immigrants regardless of their background, and invest fully in their health care, reproductive rights and ability to contribute to the economy and society. The ongoing attacks against immigrants’ health insurance coverage have helped clarify how policies around immigration, health care and reproductive rights are inherently intertwined, and that a more progressive vision for the United States must address all of these issues collectively.

The Law Before the Trump Administration

In 1996, Congress used its platform of "welfare reform" to restrict immigrants’ access to numerous federal programs, including Medicaid coverage, by deeming most immigrants ineligible for the first five years in which they have lawful status in the United States.1 States have the option to make exceptions for children and pregnant women.2 That restriction served both to undermine the growing importance of Medicaid for the U.S. health insurance system and to dovetail with separate anti–immigration legislation pushed through that year under Congress’s new Republican leadership.3 The same restriction was applied to CHIP when it was created in 1997.

Similarly, conservative opponents of the ACA used the possibility of coverage for undocumented immigrants as a wedge issue during debate over passage of the legislation and continuing afterwards. Their efforts led proponents of the law to bar those immigrants from coverage entirely under the ACA’s insurance marketplaces and helped conservatives undermine the concurrent push for comprehensive immigration reform. Insurance coverage for undocumented immigrants was seen as such a political third rail that the Obama administration extended the ACA’s ban to recipients of its Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program when it created that program in 2012, despite the policy’s purpose to provide relief to eligible immigrants to live and work unfettered in the United States.

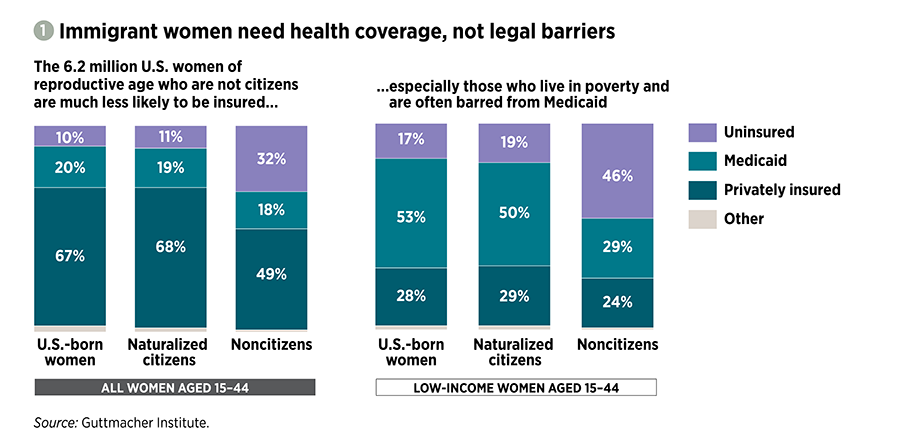

These federal restrictions have been harmful for immigrants’ health and interfere with their basic right to protect their own and their families’ health and economic well-being. In large part because of these restrictions, three times as many noncitizen immigrant women of reproductive age (15–44) living in the country in 2018 were uninsured as either naturalized citizens or U.S.-born women (32% vs. 11% and 10%, respectively; see figure 1).4

Those inequities are especially striking among reproductive-age women with incomes below the federal poverty level, a group in which immigrant women are overrepresented (the federal poverty level is $21,720 for a family of three in 20205). In 2018, almost three times as many noncitizen immigrant women in this category were uninsured as women born in the United States, and the proportion with Medicaid coverage was roughly half.4

Lack of health insurance coverage constrains immigrant women’s ability to obtain contraceptive care, maternity care and other preventive sexual and reproductive health care services. Only half of immigrant women at risk of unintended pregnancy have received contraceptive care in the previous year, compared with two-thirds of U.S.-born women.6 Many pregnant immigrant women qualify for Medicaid coverage solely for labor and delivery, leaving them unable to afford prenatal care. And research suggests that immigrant women are less likely to receive other preventive services, such as Pap tests, hepatitis B vaccinations and mammograms.

Public Charge

The Trump administration has taken multiple steps to build on this already harmful and xenophobic baseline of excluding immigrants from access to health coverage and care. In August 2019, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) finalized its expanded "public charge" regulation, designed to make it more difficult for immigrants with low or moderate incomes to enter the country or stay as permanent residents.7 The classist concept of public charge has been part of U.S. immigration policy since 1882, when the law prohibited admission of "any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge."8 An individual could be considered a "public charge" (and thus ineligible for entry or permanent legal residency) if they were currently or expected to be reliant on governmental cash assistance or publicly funded long-term institutional care (such as in a psychiatric hospital).9 In the intervening years, "public charge" has been used as an excuse to discriminate against many marginalized groups, such as people with disabilities and LGBTQ+ immigrants.10

The updated regulation vastly expands the scope of programs included and compounds how their use is measured.11 The federal government will now count many non-cash benefits—including Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Section 8 housing assistance—against immigrants. The regulation designates an immigrant as a public charge if that person receives, or is deemed likely to receive, 12 or more months of public benefits within a 36-month period, with each benefit counted separately. For example, one calendar month of both Medicaid and SNAP benefits will count as two months. The regulation also evaluates individuals’ likelihood of becoming a public charge based on their age, health, family status, financial status, education, skills and English proficiency, thus perpetuating existing social, racial and economic inequities.

Under the regulation, Medicaid coverage for pregnant women, for people younger than 21 and for emergency care (such as for labor and delivery) for people otherwise disqualified from Medicaid because of their immigration status does not count toward the 36-month limit.11 In March 2020, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, an agency under DHS, announced that testing, preventive care or treatment for COVID-19 (caused by the novel coronavirus) will not be used against immigrants in a public charge test, even if such treatment is provided or paid for by one or more public benefits.12 But there are no exceptions for other reproductive health services, such as family planning and STI care under full-benefit Medicaid coverage, coverage under a state’s Medicaid family planning expansion program, or coverage under Medicaid’s breast and cervical cancer treatment program.

The U.S. Department of State issued its own parallel interim final public charge regulation in October 2019.13 This regulation aligns its definition of public charge with that of DHS, meaning that immigrants who are expected to use public services such as Medicaid could be blocked from entering the country. The U.S. Department of Justice is reportedly drafting its own version of the public charge regulation that would affect deportation decisions.14

There have been many court cases challenging these changes to the public charge definition. By October 2019, federal judges had issued five preliminary injunctions blocking the DHS public charge regulation, including three that were nationwide in scope. These decisions temporarily halted the regulation’s implementation. In January 2020, in a 5–4 split decision, the U.S. Supreme Court granted the Trump administration permission to enforce the regulation as litigation continued in lower courts, and the administration implemented the public charge regulations starting on February 24, 2020.

Presidential Proclamation

In October 2019, the Trump administration released a presidential proclamation that aimed to bar entry to the country unless immigrants could prove either that they could secure health insurance coverage within 30 days of entering the United States, or they would have the financial resources to pay out of pocket for "reasonably foreseeable medical costs."15 The acceptable list of health insurance choices excludes government-subsidized coverage from the ACA’s marketplaces, as well as Medicaid for anyone older than 18—meaning that the administration is excluding the most affordable options for many people with low incomes.

This proclamation parallels the rhetoric of public charge, by wrongly arguing that immigrants are a burden on the U.S. health care system and American taxpayers. The proclamation also directs federal agencies to produce regular "Reports on the Financial Burdens Imposed by Immigrants on the Healthcare System," creating a self-perpetuating argument to support the policy.

The proclamation also bolsters the Trump administration’s attempts to undermine the ACA. Two of the types of insurance coverage acceptable under the proclamation are short-term plans and catastrophic plans. Short-term plans typically offer only the most basic coverage and do not need to meet the baseline requirements of the ACA. Catastrophic plans are usually only available to people younger than 30 and have low monthly premiums with very high deductibles, intended to cover only a worst-case scenario.16 The proclamation essentially would force immigrants without employer-sponsored health insurance into plans that would by definition underinsure them.

A federal district court in Oregon took swift action in November 2019 to temporarily block the proclamation nationwide. The court reasoned that the "president offers no national security or foreign relations justification for this sweeping change in immigration law."17 The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals denied the federal government’s request to lift the injunction, and the proclamation remains blocked as the question of its legality makes its way through the courts.

Chilling, Counterproductive and Cruel

Through the public charge regulation and the presidential proclamation, the Trump administration is attempting to change immigrants’ health insurance eligibility and immigration policy writ large without the consent of Congress. These actions could be devastating for immigrants and their family members at every step of the way toward residency and citizenship.

The public charge regulation will prevent people already present in the country from accessing health insurance coverage and health care, and knowledge of the regulation is already leading some immigrants to avoid using publicly funded programs.18 For example, according to one estimate by the Migration Policy Institute, there are 22.7 million people in the United States—including 10.3 million noncitizens—who make use of or have a family member who makes use of Medicaid or other programs that fall under the purview of the public charge regulation.19 Although the majority of these individuals would not actually be subject to the public charge test because of their immigration status, experts expect a large proportion to avoid accessing care via those programs.20 Another study, by the Kaiser Family Foundation, estimated that more than half of noncitizens without a green card lack private health insurance and projected that several million immigrants will disenroll from Medicaid as a result of the regulation.21

If implemented, the presidential proclamation would prevent many people from entering the United States at all. A Migration Policy Institute analysis of the president’s proclamation found that 65% of green card holders recently admitted to the United States were either covered by public insurance or were uninsured, and thus would have been excluded under such a regulation unless they could prove they had sufficient wealth to cover their own care.22 The State Department estimated that 450,000 visa applicants would be subject to the proclamation, translating to as many as 293,000 visa rejections due to the proclamation alone. The district court judge who temporarily blocked the proclamation cited this impact in his ruling.17

The collective weight of these anti–immigration policies, along with the Trump administration’s high-profile deportation efforts, has a chilling effect that has already manifested by people being overly cautious in using any publicly funded programs.23 For example, an Urban Institute study found that one in seven adults in immigrant families said they or a family member avoided a program like SNAP or Medicaid in 2018 because they feared risking their future green card status.24 And a Kaiser Family Foundation survey of community health centers in 2019 found that nearly half reported that many or some of their immigrant patients refused to enroll in Medicaid in the past year.25

These anti–immigration policies ignore the fact that for many people in the United States, government-subsidized programs such as Medicaid, CHIP and subsidized ACA health plans are the only affordable insurance option available: Just 30% of U.S. workers with incomes below the federal poverty level are even offered employer-sponsored insurance, and many of them cannot afford the premiums.26 This problem is heightened for immigrants because they are more likely than citizens to have low incomes and to work in industries that do not offer health insurance to employees.27

These policies also ignore the facts that immigrants are an economic boon for the country and pay their fair share of U.S. taxes.28 And they even run contrary to the Trump administration’s stated goal of ensuring that immigrants to the United States are "self-sufficient," because they deny people affordable health coverage that has demonstrated long-term health and financial benefits.29,30

Expanding Coverage for Immigrants

Against the backdrop of this administration’s punitive anti–immigrant campaign, advocates are fighting back. They are rejecting this current onslaught by fighting the Trump administration’s policies in court and trying to get Congress to bar the administration from spending money to implement these policies. And groups like the Protecting Immigrant Families coalition have developed resources for both individuals and families who may be impacted, as well as for advocates looking to join the fight.31,32

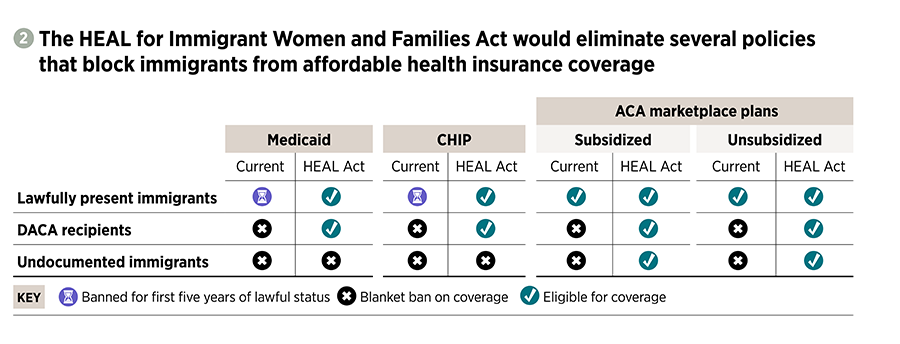

Moreover, advocates are working to repeal the long-standing and harmful restrictions on immigrants’ health coverage that are rooted in anti–immigrant sentiment and racism. One of these efforts is the Health Equity and Access under the Law (HEAL) for Immigrant Women and Families Act. This bill would greatly expand immigrants’ eligibility for health insurance coverage and access to care, including sexual and reproductive health services.

Specifically, the bill would boost eligibility for three main groups (see figure 2):

- Lawfully present immigrants: Enable all lawfully present immigrants to enroll in Medicaid and CHIP if they are otherwise eligible, by eliminating the ban on enrollment that is currently in place for five years after an immigrant has established lawful status.

- DACA recipients: Enable all lawfully present people granted deferred action—most notably, young people with DACA status—to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP, if they are eligible, and to buy ACA marketplace coverage and obtain the ACA’s affordability subsidies.

- Undocumented immigrants: Allow all immigrants, regardless of legal status, to buy ACA marketplace coverage and obtain the ACA’s affordability subsidies.

The bill would also restore Medicaid eligibility for Compact of Free Association migrants (citizens of the Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Palau), who were inadvertently excluded from Medicaid coverage by the 1996 welfare reform law. By striking down barriers to immigrants’ access to affordable public and private health coverage, the HEAL for Immigrant Women and Families Act would improve their ability to obtain the health care information and services they need. The bill would also send a strong signal by Congress to counter the Trump administration’s demonstrated hostility to immigrants’ health and rights.

In addition to HEAL, Congress currently has several proposed health care reform bills, some of which would expand health insurance coverage to immigrants.33 Notably, the House and Senate Medicare for All proposals would enroll all U.S. residents in a new national health insurance program, with no exclusions for either documented or undocumented immigrants, and several proposals would extend a public insurance option to documented immigrants.

A More Humane System

The current climate of uncertainty and threat is instilling fear in noncitizens of any immigration status about accessing not just health care,21 but a wide variety of services they need.34 Individuals and families are left to navigate a changing landscape with potentially devastating consequences, forced to make difficult choices to maintain their safety. Damage has already been done to break immigrant communities’ trust in systems that are supposed to provide assistance, and with the adoption of the draconian public charge regulation, the damage continues.

Fighting bald-faced anti–immigrant policies and clearing the numerous institutional barriers to immigrants’ health insurance coverage are necessary steps toward an inclusive, healthy United States; but that is not where the work ends. To truly address the deep intersections affecting some of our most vulnerable community members, we must work toward stronger and more humane immigration policy, health care policy, and sexual and reproductive health policy.

The Trump administration is targeting points where immigrants’ rights, health care, and sexual and reproductive rights meet as places of weakness, vulnerable to these attacks. But this intersection is one of strength, where advocates from each community recognize that restrictions and callousness are cross-cutting and these issues are inextricably intertwined; so must be our collective, coordinated response.