Texas is the second largest state in the country, and has the second largest population. Indeed, everything is bigger there—including the need for affordable health coverage, and for accessible sexual and reproductive health services and information. More than six million Texans have no health insurance of any kind, including 2.4 million adult women.1,2 And more Texas women are in need of subsidized family planning services than anywhere else in the country, except California.3

The response of Texas’ elected leaders in terms of policies and programs that could alleviate these conditions, meanwhile, has ranged from apathy to outright hostility. Conservatives have controlled Texas’ state government and limited access to health coverage and care for years, but the 2010 elections swept in more significant majorities of more staunchly conservative lawmakers, who have pursued a more aggressively hostile agenda. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted earlier that same year, was met with fierce opposition among conservatives in the state. Gov. Rick Perry (R) has gone so far as to say that no one in Texas has to worry about access to health care, because hospital emergency rooms cannot turn people away.4 As for reproductive health and rights, Perry and his allies have intensified their attacks on programs, policies and providers since 2010, while Texas women seeking reproductive health care are left to navigate one of the most restrictive environments in the country.

The confluence of the widespread need for affordable health care—including sexual and reproductive health care—and neglectful or hostile state policies is particularly extreme in Texas. Moreover, because of the sheer size of the population, the impact is especially significant. The dynamics in Texas are not unique, however. Too many other states are going down the same path, potentially leading to similarly harsh consequences for the women and families who live there.

Outsized Need for Care

The health care needs of people living in Texas are not only defined by the sheer size of the state and its population, but also by its demographic characteristics. About one-quarter of adult women in Texas live below the federal poverty level.5 In addition, income inequality in the state is among the most severe in the country, and it is growing: The poorest households have experienced an average 10% drop in income over the last decade.6 Moreover, Texas has large proportions of women who are Hispanic, foreign-born, young, or living in rural areas—all characteristics linked to limited access to health care and heightened risk of negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

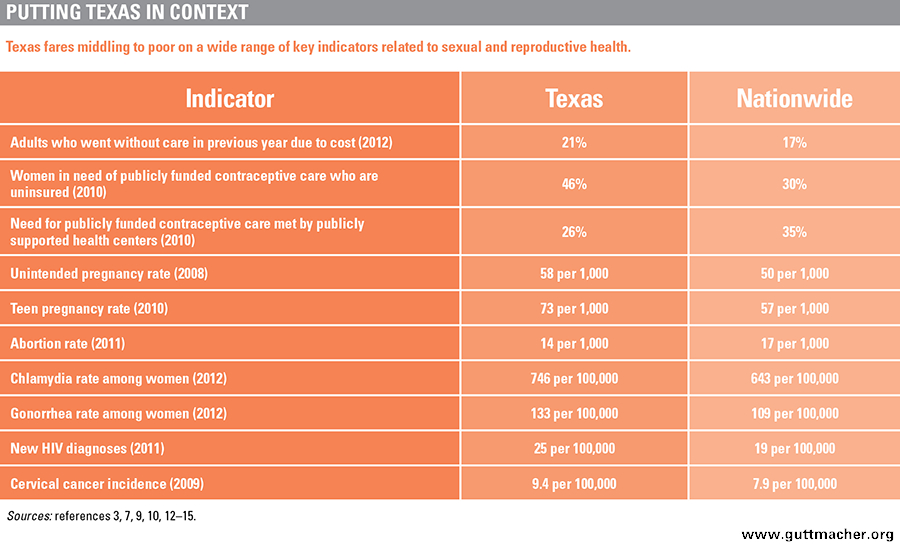

Given these population demographics and the anti–public health, anti–sexual and reproductive health policies prevailing in Texas, it is unsurprising that the state consistently rates as mediocre or poor on measures of access to care and health outcomes. Indeed, the Commonwealth Fund recently ranked Texas 44th in general health system performance, and in the bottom three states in specific measures of health care access and affordability, and prevention and treatment.7

Texas has the highest proportion of uninsured individuals of any state,1 as well as the highest proportion of uninsured adult women.2 The Commonwealth Fund’s report found that in 2012, one-fifth of adults in Texas had gone without care in the previous year because of cost (see table).7 And according to a recent analysis by the National Women’s Law Center, nearly 60% of uninsured low-income women in Texas reported not receiving needed medical attention in the previous year because of cost—twice the proportion of low-income women with health coverage.8 Uninsured low-income women were also much more likely to have gone without a regular checkup, mammogram or Pap test in recent years.

Moreover, in 2010, 1.7 million Texas women were in need of publicly funded contraceptive services and supplies, which means that they were aged 13–44, sexually active and capable of becoming pregnant but were not trying to do so, and they either had family incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level or were teens (who are presumed to have a low personal income).3 Notably, the number of Texas women needing publicly funded contraceptive services grew by 30% since 2000, driven by an increase in the number of poor women living in the state. Nearly half (46%) of Texas women in need of publicly funded contraception were uninsured in 2010—the highest proportion in the nation.

However, even as the number of Texas women needing to rely on the state’s publicly funded family planning effort has increased, the program’s capacity has decreased. In 2010, there were 55 fewer safety-net health centers providing publicly supported contraceptive care in Texas than nine years earlier, and the remaining providers served 20% fewer women than before.3

Limited access to contraceptive care places women at heightened risk of unintended pregnancy. In 2008, there were 58 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 Texas women, substantially above the national median of 50 per 1,000.9 The state fares particularly poorly in regard to teen pregnancies: In 2010, Texas had the third highest teen pregnancy rate in the country, the fourth highest teen birthrate and the highest prevalence of repeat teen births.10,11 Furthermore, despite the state’s long history of enacting laws hostile to abortion rights, women in Texas continue to have abortions at about the same rate as women nationwide, because so many pregnancies in Texas are unintended and the vast majority of abortions are preceded by an unintended pregnancy.12

Finally, lack of health insurance coverage and of access to family planning–related services, such as STI screenings, contribute to other negative sexual health outcomes. Texas women experience rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis that are all well above the national average.13 Moreover, Texas ranks among the top 10 states by rate of new HIV diagnoses and by cervical cancer incidence.14,15

Counterproductive Policy Responses

Texas lawmakers have access to these lackluster health indicators, yet at seemingly every turn have embraced and endorsed policies that more often than not can only exacerbate the situation. The consequences for the health and welfare of Texas women and the population overall are ominous.

Health Insurance Coverage

Despite having the highest rates of uninsured people in the country, Texas lawmakers have time and again limited Texans’ affordable coverage options. For instance, the income eligibility ceiling for the state’s Medicaid program is the second-lowest in the country: Childless adults are unable to enroll altogether, and the eligibility level for parents is just 19% of the federal poverty level or $3,760 for a family of three.16,17

Astonishingly, the Texas legislature recently debated the notion of dropping out of Medicaid entirely because of the prospect of increasing costs, even though almost all of those additional costs would be borne by the federal government for years to come. Under the ACA, as interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012, states have the option to expand their Medicaid programs to cover residents with an income of up to 138% of the federal poverty level. The federal government will cover 100% of those costs through 2016 and then will phase its contribution down to no less than 90% in 2020 and thereafter. Governor Perry "proudly" rejected the expansion of Texas Medicaid, as well as the state’s implementation of its own health insurance marketplace under the ACA, "because both represent brazen intrusions into the sovereignty of our state," and neither "would result in better ‘patient protection’ or in more ‘affordable care.’"18 Moreover, during its 2013 session, the Texas legislature passed a law to demonstrate its own opposition to the ACA, which requires the state to receive legislative approval to expand Medicaid under the ACA.

Texas is currently one of about half of states that have not yet expanded their Medicaid programs.19 The realities of this decision flout the needs of the uninsured, as well as conservatives’ fiscal concerns: More than one million low-income Texans are left in a coverage gap, meaning they have incomes too high to qualify for Texas Medicaid, but too low to qualify for federal subsidies to purchase private coverage through the state’s federally administered health insurance marketplace.20 In fact, Texas residents account for more than one-fifth of people in this coverage gap nationwide. If Texas were to expand its Medicaid program, it is estimated that the state’s uninsured population would decline by about half by 2022, during which time the state would receive nearly $66 billion in federal funding, while increasing its own expenditures by $5.7 billion (a 3.5% increase over current levels) and saving $1.7 billion in uncompensated care.21

Family Planning Effort

For many years, Texas had maintained reasonable investments in family planning services. In 2007, Texas joined about half the states in expanding Medicaid eligibility specifically for contraceptive and related care, by creating Texas’ Women’s Health Program for adult women with incomes below 185% of poverty. In 2011, however, the state took several major steps to reverse course, largely motivated by the goal of putting Planned Parenthood out of business in Texas.

First, the state moved to ban Planned Parenthood health centers from participating in the Women’s Health Program, based solely on the fact that these centers were associated with other sites where abortions were provided; Planned Parenthood health centers had been serving about four in 10 women in the program statewide, and some sites served as many as eight in 10 women within their service areas.22 The Obama administration made clear that Texas’ action violated federal law by discriminating against qualified providers. Gov. Perry remained defiant, which led to his state’s losing all federal support for the program—$9 for every state dollar spent. As of January 2013, the program is an entirely state-administered effort with a more limited provider network and substantially fewer enrollees, and it delivered thousands fewer contraceptive and related services in each of its first months of operation.23

Also in 2011, the legislature reallocated two-thirds of the budget for the state’s family planning program (separate from the Women’s Health Program) to other efforts, which resulted in an annual budget of only about $19 million. Additionally, lawmakers tiered the types of providers who could receive these remaining funds. Health departments have top priority, followed by community health centers; specialized family planning centers are disadvantaged, only able to apply for any funds that remain. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, in 2013, the state’s family planning program served less than one-quarter of the women it had served in 2011.24 Departmental data also showed that the cost to the state to provide family planning care increased dramatically, from $206 per client to $240. This is unsurprising given that funds were systematically directed away from specialized family planning centers, which are prepared to see the highest volume of patients most cost-effectively.

According to researchers at the Texas Policy Evaluation Project, who have been studying the impact of these collective family planning funding cuts and restrictions, dozens of clinics closed in 2012, about half of them family planning–focused sites; dozens of those still open have had to reduce their hours, patient loads and scope of services to accommodate their smaller budgets.25 These cuts have not only limited women’s contraceptive choices, but also Texans’ ability to obtain related services, including STI/HIV tests, Pap tests and other preventive care, from trusted providers who specialize in the delivery of such sensitive and confidential care.

In 2013, legislators attempted to mitigate public outcry and increasing costs to the state by restoring some of the lost funding for the state’s family planning program and by creating a new program to deliver primary care—including family planning services—to women aged 18–65. However, family planning advocates are skeptical about how much ground can be regained, let alone if any progress can be made, because of the massive disruption lawmakers caused to the delivery of family planning care and because there remains a net cut in funding.

Meanwhile, the cycle for the Title X grant administered by the state came to an end in 2013, which required the state to reapply and created the opportunity for other entities to apply. Ultimately, the Title X grant was awarded to the Women’s Health and Family Planning Association of Texas, instead of the Texas Department of State Health Services. For the first time, the state is not administering Title X funds, which means they are no longer subject to the tiered provider requirement. This change may be particularly beneficial in more remote, economically depressed communities such as the Rio Grande Valley, where after four Planned Parenthood health centers closed in the wake of budget cuts, one has been able to reopen with the restoration of Title X support (see box).

The Particular Needs of Immigrant Women

In 2011, Texas was home to more than four million immigrants; only California and New York had more, although the immigrant population had grown far faster over the last decade in Texas than in either of these two states.26 Moreover, an estimated 1.65 million undocumented immigrants live in Texas, the second-largest population among the states.27 As in the rest of the country, many immigrants in Texas are legally barred from obtaining health insurance coverage solely on the basis of their immigration status (see "Toward Equity and Access: Removing Legal Barriers to Health Insurance Coverage for Immigrants," Winter 2013).

Yet, Texas has taken a conservative policy approach with regard to covering its immigrant population: Although Texas takes advantage of federal options to provide prenatal care to women regardless of their immigration status and to cover all lawfully residing children, it is one of a few states where most immigrants who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid cannot enroll, even if they have resided in the United States for at least five years.28 Other states with large immigrant populations, including California and New York, have done much more to address these communities’ needs, using state funds to cover some immigrants ineligible for federal programs.

Given the unique barriers they face to obtaining health coverage, immigrant women, especially those who are low-income, often rely on safety-net providers for both family planning and abortion care. As illustrated in a report by the Center for Reproductive Rights and the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, the attacks leveled by conservative Texas lawmakers have hit these women particularly hard.29 The report describes how the women of the Lower Rio Grande Valley—disproportionately Latina and immigrants—have seen their trusted local reproductive health providers close, and have suffered health and fiscal costs of going without preventive sexual and reproductive health services. Moreover, according to the Texas Policy Evaluation Project, more than 2,600 women in the Rio Grande Valley obtained an abortion in 2011.30 Given recent clinic closures, these women—many of whom are unable to travel away from home because of their immigration status—will be hard-pressed to obtain abortion care from a qualified provider.

Sex and HIV Education

For decades, Texas’ lawmakers have carried out an ideological campaign against enabling young people in the state to have access to honest information on sex, including pregnancy and STI prevention. When asked in a 2010 interview about why Texas maintained its focus on abstinence-only-until-marriage education despite the state’s high rate of teen pregnancy, Gov. Perry said only, "abstinence works…from my own personal life, abstinence works," and that he would not advance the availability of information on safe sex to Texas teens.31

In the mid-1990s, Texas became an early adopter of the abstinence-only approach to sex education. The state does not mandate sex education or HIV education in its schools; however, if such education is provided, it must stress abstinence, the importance of having sex only within marriage and negative outcomes of teen sex and pregnancy.32 In addition, sex education in Texas is not required to be medically accurate or culturally appropriate and unbiased. Furthermore, Texas is one of just three states that mandate the inclusion of only negative information on sexual orientation.

Moreover, the state has been one of the largest recipients of federal funding to provide abstinence-only education—funding championed by former President (and former Texas governor) George W. Bush. And although a handful of local entities in Texas have received grants for more comprehensive, evidence-based programs, Perry has forced the state to turn down millions in federal funding made available to the state through the Personal Responsibility Education Program, which supports education on contraception and preparing adolescents for adulthood, as well as abstinence.

Abortion Access

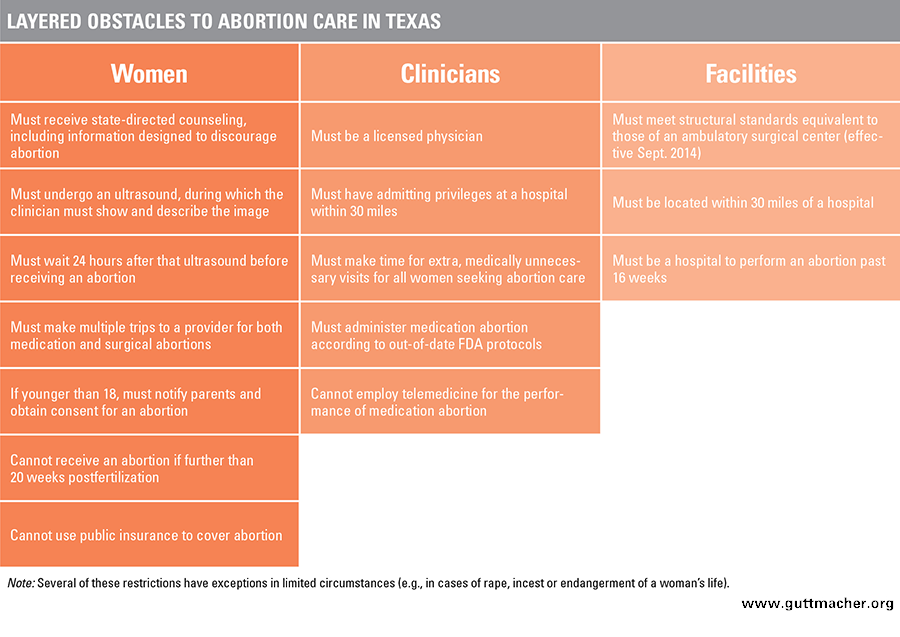

Texas lawmakers have waged a concerted campaign against abortion rights, and have enacted a raft of measures that individually are designed to impede women’s access to abortion care and collectively increase the likelihood of achieving that goal (see table). Just last year, Gov. Perry and the state legislature were so intent on piling on more abortion restrictions that they convened a special session for the sole purpose of reviving a multifaceted antiabortion bill that failed during the regular legislative session. The new law bans abortion after 20 weeks from fertilization (approximately 22 weeks from a woman’s last menstrual period), requires clinicians to follow outdated prescribing regimens for medication abortion, mandates that physicians have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, and as of September 2014, requires facilities where either surgical or medication abortions are provided to be the functional equivalent of ambulatory surgical centers.

Texas lawmakers repeatedly insisted that their motivations were to promote and protect women’s health. The physicians and hospitals who actually provide that care, however, beg to differ. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Texas Medical Association both opposed the bill, citing physicians’ concerns that these laws will interfere in the physician-patient relationship and inappropriately intervene in the regulation of medical practice.33,34 The Texas Hospital Association expressed its opposition specifically to the requirement that abortion providers have hospital admitting privileges. It argued that obtaining admitting privileges is a time-consuming and expensive process that does nothing to protect women’s health, as any woman needing emergency care can already receive such care at the hospital.35

Following these most recent restrictions, the availability of abortion providers has dwindled. In 2011, before these laws were enacted, Texas had 46 free-standing abortion clinics—the type of provider most women turn to for abortion care.12 The first wave of clinic closures following the 2013 restrictions came as clinicians were required—but often unable—to obtain hospital admitting privileges. Notably, only 27% of Texas’ 630 hospitals are located in rural areas, which places rural abortion providers in particular jeopardy from this requirement.36 For now, at least, about two dozen abortion clinics remain open.

Once abortion providers start having to comply with ambulatory surgical center standards in September, however, the number of clinics will almost certainly drop significantly and all but eliminate access in rural areas. Already, large areas of Texas are without abortion clinics, including the Lower Rio Grande Valley and southeast Texas. In March, Whole Women’s Health closed two of its abortion clinics, the last in each of these areas, citing the new restrictions. According to the Texas Policy Evaluation Project, the nearest clinic to the Rio Grande Valley that currently meets ambulatory surgical center standards is in San Antonio, about 250 miles away; the nearest clinic to the eastern Texas city of Beaumont—where the Whole Women’s Health provider had been—is 90 miles away in Houston.37 And options for women who might seek abortion services in neighboring states are increasingly limited, as Arkansas, Louisiana and Oklahoma all have numerous abortion restrictions of their own (see "A Surge of State Abortion Restrictions Puts Providers—and the Women They Serve—in the Crosshairs," Winter 2014).

More restrictions on abortion care undoubtedly will succeed in blocking access for many women, disproportionately affecting those unable to travel sometimes very long distances in this very large state and those who cannot afford time away from home. None of this affects the need for care, however. On the basis of survey data from women seeking abortion services in 2012, prior to Texas’ newest abortion restrictions, researchers at the Texas Policy Evaluation Project found higher rates of self-induction compared with nationally representative data.30 They anticipate that Texas women would increasingly attempt to self-induce abortion as they lose access to quality care, especially those living in impoverished areas along the Mexico border who have easier access to the abortion-inducing drug misoprostol and potentially more familiarity with the practice.

Health Care Dystopia

Texas is far from alone in terms of the breadth and depth of its attacks on women’s reproductive health and its regressive approach to public health more generally. Because of its size and the number of people affected by its policies, however, it stands as a paradigm of ultraconservative health policies that activists and lawmakers in other states and at the federal level seek to emulate. And given that Texas’ governor and legislature are philosophically in synch, there is no political brake on whatever new, extreme ideas arrive on the agenda there. Even the state courts and the federal courts overseeing Texas are similarly aligned, which is why all of Texas’ antiabortion laws have gone into effect and been upheld so far—unlike in some other states where successful legal challenges have delayed or blocked the implementation of similar laws.

Texas stands as a warning sign for the rest of the nation. The poor health indicators and the negative trends in the state are indisputable. Its population is large, far-flung and diverse, and so many of its residents live in poverty and are unable to obtain affordable coverage and care. Ignoring these realities by excluding the vast majority of those in need from Medicaid and refusing to accept billions in federal dollars to expand the program can only exacerbate the conditions under which underserved Texans already live. In clamping down on the availability of safe and high-quality abortion care, Texas lawmakers refuse to acknowledge that the most effective way to reduce the need for abortion has always been improved contraceptive use and the prevention of unintended pregnancies (see related article). And lawmakers’ blinders to this relationship are made all the more clear by their deep cuts in family planning funding and moves to disqualify Planned Parenthood centers and other trusted community providers from participating in the state-run efforts that remain. As staunchly conservative Texas lawmakers have taken steps to eschew federal aid and to dictate access to health coverage and care—especially family planning and abortion services—on their own terms, the health and well-being of their own people are only at greater risk.