An unprecedented wave of state-level abortion restrictions swept the country over the past three years. In 2013 alone, 22 states enacted 70 antiabortion measures, including previability abortion bans, unwarranted doctor and clinic regulations, limits on the provision of medication abortion and bans on insurance coverage of abortion. However, 2013 was not even the year with the greatest number of new state-level abortion restrictions, as 2011 saw 92 enacted; 43 abortion restrictions were enacted by states in 2012.1

What accounts for the spike in abortion restrictions? A few reasons stand out. First, antiabortion forces took control of many state legislatures and governors’ mansions as a result of the 2010 elections, which allowed them to enact more restrictions than was politically feasible previously. Second, the politics surrounding the Affordable Care Act, enacted in March 2010, reignited a national debate over whether government funds may be used for abortion coverage and paved the way for broad attacks on insurance coverage at the state level. The relative lull in antiabortion legislative activity seen in 2012 is explained in part by the legislative calendar: North Dakota and Texas, for example, did not hold legislative sessions in 2012. They made up for it last year, though: Together, these two states enacted 13 restrictions in 2013.

The wave of state-level abortion restrictions has some parallels in Congress, where the House of Representatives has waged its own unceasing attack on abortion rights. Defending against the onslaught has been critical, but now prochoice activists are starting to go on the offense. A handful of states have moved to improve access to abortion, and proactive legislation has been introduced in Congress aimed at stemming the tide of restrictive laws designed to place roadblocks in the path of women seeking abortion care. Although this emerging campaign may be more successful and take hold faster in some places than others, it marks an important shift toward reshaping the national debate over what a real agenda to protect women’s reproductive health looks like.

A Landscape Transformed

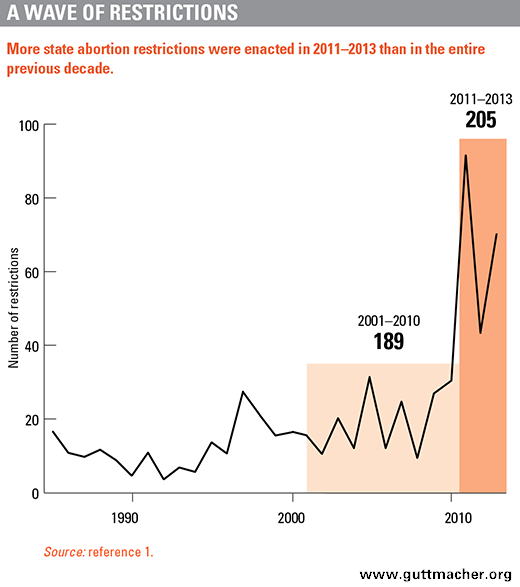

Abortion restrictions at the state level are hardly new. States have long sought to discourage women from obtaining an abortion by, for example, mandating that women receive biased counseling or imposing parental involvement requirements for minors. Over the past three years, however, a startling number of states have passed harsh new restrictions. In 2011–2013, legislatures in 30 states enacted 205 abortion restrictions—more than the total number enacted in the entire previous decade (see chart).1 No year from 1985 through 2010 saw more than 40 new abortion restrictions; however, every year since 2011 has topped that number.

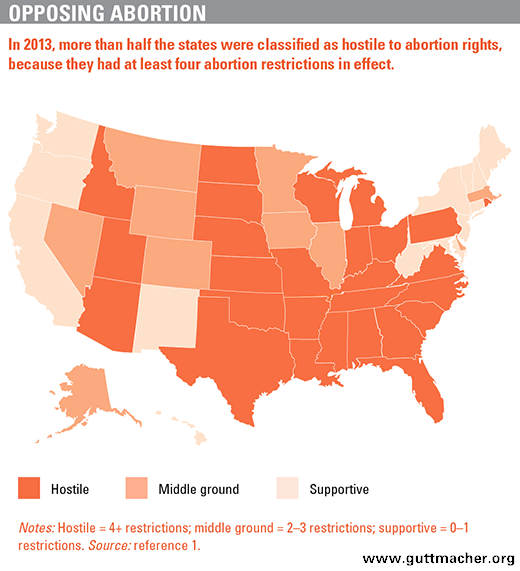

In terms of sheer numbers, this wave of new restrictions has dramatically shifted the abortion policy landscape. To assess how and where the volume of abortion restrictions changed over time, analysts at the Guttmacher Institute identified 10 categories of major abortion restrictions and considered whether—in 2000, 2010 and 2013—states had in place at least one provision in any of these categories.1,2 A state was considered "supportive" of abortion rights if it had enacted provisions in no more than one of the restriction categories, "middle ground" if it had enacted provisions in two or three, and "hostile" if it had enacted provisions in four or more.

According to the analysis, the overall number of states hostile to abortion rights has grown since 2000, while the number of supportive and middle-ground states has shrunk. In 2000, 13 states were hostile to abortion rights; by 2010, that number was 22, and by 2013, it was 27 (see map).1 Over the same period, the number of states supportive of abortion rights fell from 17 in 2000 to 13 in 2013, and the number of middle-ground states was cut in half, from 20 to 10.

Notably, the cohort of states already hostile to abortion rights was responsible for nearly all of the abortion restrictions enacted in 2013. And in many of these states, the number of abortion restrictions on the books has started to pile up. In 2000, only two states—Mississippi and Utah—had five of the 10 major types of restrictions in effect. By 2013, 18 states had six or more major restrictions, and seven states had eight or more. Louisiana, the most restrictive state in 2013, had 10.

Creating a Hostile Climate

Four categories of major abortion restrictions dominated the legislative scene in 2011–2013: targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP), limits on the provision of medication abortion, bans on private insurance coverage of abortion and bans on abortion at 20 weeks from fertilization (the equivalent of 22 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period).1 States enacted 93 measures in these four categories in 2011–2013, compared with 22 over the previous decade. These restrictions, especially their cumulative effects in a given state, may prove to accomplish more in terms of impeding access to care than the previous decades of restrictions, noisy clinic blockades and even outright violence ever have.

TRAP Provisions

To date, 26 states have laws or policies that regulate abortion providers and go beyond what is necessary to ensure patients’ safety.3 Most often, the restrictions dictate that abortions be performed at sites that are the functional equivalent of ambulatory surgical centers, or even hospitals, which makes the delivery of health care services prohibitively expensive. Other TRAP laws require clinicians at abortion facilities to have admitting privileges at a local hospital or mandate transfer agreements with hospitals—setting standards that are extremely difficult for providers to meet and effectively giving hospitals veto power over whether an abortion clinic can exist (see "TRAP Laws Gain Political Traction While Abortion Clinics—and the Women They Serve—Pay the Price," Spring 2013).

These regulations are proving to be especially powerful. For example, because of new requirements in Virginia, all abortion clinics in the state must now comply with standards based on those for hospitals that mandate dimensions for procedure rooms and corridors, and include requirements for ventilation systems, parking lots and entrances. Already, one abortion clinic there has been forced to close as a result of the requirements, and the state department of health estimates that the cost of compliance at other clinics will approach $1 million per site.4

In Texas, at least a dozen of the state’s abortion clinics have been forced to close since a law took effect in late 2013 requiring that abortion facilities meet the standards for ambulatory surgical centers and that their clinicians have hospital admitting privileges.5 Because the clinic regulations have not been fully implemented yet, the full impact of TRAP provisions in Texas remains to be seen. There is a growing concern, however, that only a handful of the existing abortion clinics there will meet the requirements for ambulatory surgical centers and have clinicians who can obtain the necessary admitting privileges to remain in practice.6

Limits on Medication Abortion

States have enacted several types of restrictions targeting medication abortion. As of April 2014, three states—Arizona, Ohio and Texas—require that medication abortion protocols hew closely to an outdated regimen specified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when medication abortion was first approved;7 those laws prohibit alternative, evidence-based protocols in wide use for at least the past decade. Fourteen states require that medication abortion be provided only by a physician who is in the same room as the patient.

Restrictions on medication abortion both burden women and block access to abortion in communities—particularly rural areas—where the lack of abortion providers serves as a barrier to care (see "Medication Abortion Restrictions Burden Women and Providers—and Threaten U.S. Trend Toward Very Early Abortion," Winter 2013). When the FDA-approved regimen is required, it leads to a host of problems for women, including that women are subject to a higher dose of medication, must make multiple visits to the doctor and are prohibited from self-administering the drug in the privacy of their home. When physicians are the only health professionals permitted to provide medication abortion (rather than physician assistants and advanced practice nurses, as well), a woman may have to wait a long time for an appointment and travel long distances to visit a clinic attended by a physician. Laws requiring the physical presence of the physician essentially rule out provision by telemedicine. Blocking the use of telemedicine—i.e., virtual consultation with a physician by video—for medication abortion jeopardizes access to early abortion care. In addition, it is out of step with the trend toward expanding the use of telemedicine in other medical specialties.

Indeed, attacks on medication abortion threaten provision of abortion at the earliest stages of pregnancy. Most women obtaining an abortion want to have it as early as they can—and today, 33% of all abortions are performed in the first six weeks of pregnancy (calculated from the beginning of the last menstrual period).8 Importantly, it is the increased availability of medication abortion that appears to be helping women obtain very early abortions. An estimated 239,400 medication abortions were performed in 2011, which represents 23% of all nonhospital abortions, an increase from 17% in 2008.9 And contrary to the fears of antiabortion activists, access to medication abortion does not lead to more abortions; indeed, even as the use of medication abortion has become more common, the abortion rate has dropped to an historic low.

Private Insurance Coverage of Abortion

Twenty-four states have laws essentially banning abortion coverage in plans that are offered through the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance marketplaces, including nine states that ban insurance coverage of abortion more broadly in all private insurance plans regulated by the state.10 This tactic represents a new angle on an old theme. At the federal level, antiabortion politicians have long interfered in poor women’s health decisions by sharply limiting abortion coverage for women who rely on Medicaid.

The impact of these restrictions is significant. Unable to use their coverage, poor women often have to postpone their abortion because of the time it takes to scrape together the funds to pay for the procedure.11 Moreover, one in four women enrolled in Medicaid and subject to these restrictions who would have had an abortion if coverage were available are forced to carry their pregnancy to term.

Better-off women without insurance coverage of abortion may not have to make the same financial sacrifices as poor women, but having to pay out of pocket for any health care takes a toll, and abortion care is no different. The whole purpose of health insurance is to ensure that individuals can manage unexpected medical bills in the case of an unplanned event. An unintended pregnancy—or a much-wanted pregnancy that goes horribly wrong—is the very definition of an unplanned event. The campaign to end abortion coverage may not be succeeding in stopping abortion entirely, but it is punishing women who need and have abortions. Moreover, it aims to further stigmatize and delegitimize abortion by isolating it as something other than the basic health care for women that it is (see "Insurance Coverage of Abortion: Beyond the Exceptions for Life Endangerment, Rape and Incest," Summer 2013).

Previability Bans on Abortion

Nine states ban abortion at 20 weeks from fertilization, based on the dubious assertion that a fetus can feel pain at that point in gestation; three other states have similar laws that are currently enjoined by the courts.12 In addition, two states enacted laws in 2013 banning abortion even earlier in pregnancy. In March 2013, the Arkansas legislature overrode a veto by Gov. Mike Beebe (D) to ban abortions occurring more than 12 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period. Later that month, North Dakota enacted a ban on abortions occurring after a fetal heartbeat is detected, something that generally occurs at about six weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period. Legal challenges were quickly filed to both measures and enforcement is blocked while litigation proceeds. Voters in North Dakota and Colorado will be asked on their November 2014 ballots to grant personhood rights to fetuses, an approach designed to ban abortion entirely. Currently, no state has a law in effect prohibiting abortions in the first trimester.

Previability abortion bans are especially perverse given the simultaneous campaign to enact laws and policies that impose waiting periods and other requirements with the express purpose of delaying women’s ability to access abortion care. According to a study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, women obtaining abortion at or after 20 weeks’ gestation had experienced more logistical delays than women receiving a first-trimester abortion.13 Women in the later abortion group were much more likely than women in the first-trimester group to report delays because they had difficulty finding a provider, raising funds for the procedure and travel costs, and securing insurance coverage.

Women Pay the Price

Antiabortion leaders disingenuously insist that these restrictions are necessary to protect women’s health and safety. The safety of abortion, however, is well established, and long-standing patient protections exist in the rare case of an emergency.14 Nonetheless, even as proponents of these harsh and punitive laws revel in their political and public relations successes, women seeking abortion must live with the consequences.

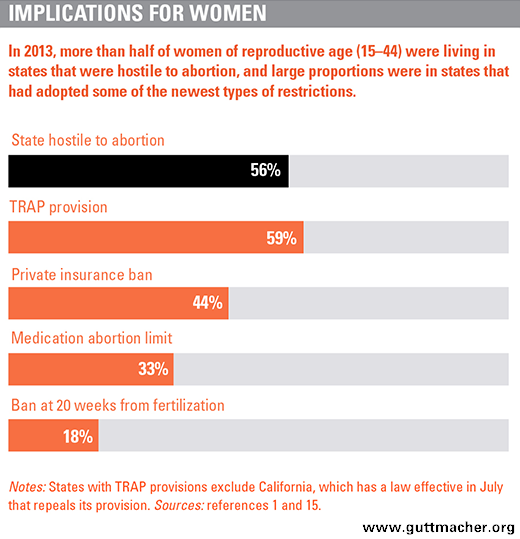

The majority of women now live in states hostile to abortion rights: Between 2000 and 2013, the proportion of women living in restrictive states almost doubled from 31% to 56% (see chart).15 The proportion living in supportive states, by contrast, fell from 40% to 31% over the same period.

Women living in the middle of the country and in the South are particularly affected. Although states in the Northeast and on the West Coast remain consistently supportive of abortion rights, a cluster of states in the middle of the country have moved from being middle-ground states in 2000 to being hostile in 2013.1 All 13 states in the South had become hostile by 2013.

Women living in hostile states face many of the same indignities when obtaining an abortion. From bogus "informed consent" procedures and waiting periods to unnecessary and costly ultrasound mandates, women seeking an abortion are subjected to restrictions not imposed on any other legal medical procedure. Fifty-nine percent of women of reproductive age live in one of the 26 states with TRAP laws and 44% of women live in one of the 24 states with bans on private insurance coverage of abortion in the new marketplaces.15 Moreover, with clinics closing in many states, locating and getting to an abortion provider are becoming increasingly difficult. Raising money not only for the procedure but also for transportation, a hotel and child care (more than six in 10 women obtaining an abortion are already mothers16) are challenges that, although often surmountable, exact additional tolls and add to delays. Simply put, restrictions on abortion make the procedure more costly—financially and in terms of women’s health and safety.

Unquestionably, abortion restrictions fall hardest upon the poorest women, the very group bearing a disproportionate burden of unintended pregnancies. In 2008, the rate of unintended pregnancy among poor women was about five times that of women with an income of at least 200% of the federal poverty level (137 vs. 26 per 1,000 women aged 15–44).17 As a result, poor women are disproportionately likely to be faced with the decision about whether to seek an abortion.

Restrictions on abortion also have serious consequences for other groups of women. Too many young women, unmarried women, women of color, immigrant women and women living in rural areas face limited options and must travel long distances to obtain an abortion, often resulting in a delay and increasing the risk of complications. Although only about 10% of women who have abortions have them after the first trimester, certain groups of women are overrepresented among such abortion patients.18 These groups include women with lower educational levels, black women and women who have experienced multiple disruptive events in the last year, such as unemployment or separating from a partner.

Fighting Back

Abortion foes have waged a relentless assault on abortion rights at the federal level as well. In 2011–2013, members of Congress introduced dozens of bills aimed at dismantling abortion rights, including those that would force abortion coverage out of all insurance plans (public or private), ban all abortions in the United States at or after 20 weeks from fertilization, or prohibit federal grants from going to medical facilities that prescribe medication abortion via telemedicine. The House passed a version of each of these provisions—at least once—over the last several years, yet abortion rights supporters in the Senate have blocked them from moving forward, and some have explicitly drawn presidential veto threats. This is in stark contrast to the rapid pace that radical antiabortion laws have been enacted across large swaths of the country, but mostly in the states controlled by politicians with an extreme antiabortion ideology.

At least one state and some lawmakers in other states are beginning to demonstrate that promoting an abortion agenda that protects women’s health is also possible at the state level. This past summer, California enacted a law that makes it legal for midlevel providers—such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants—to provide abortions in the first trimester, which expands the potential pool of qualified providers. In addition, California abortion clinics are now required to meet the same licensing and structural standards as primary care clinics, which provide basic and low-risk services; before, abortion clinics had been required to meet additional, unnecessary standards that applied only to them.

Moreover, in the opening weeks of states’ legislative sessions this year, policymakers in 15 states are making some noteworthy progress with initiatives that would protect and advance access to abortion care. For example, in Arizona, a bill was introduced to repeal a ban on the use of telemedicine for medication abortion. The New York Assembly adopted a measure that would essentially codify the Roe v. Wade decision and prohibit any interference with a woman exercising her right to obtain an abortion before viability or when necessary to protect the life or health of the woman. And in Washington, a bill passed the House that would require private insurance plans that cover maternity care to also provide abortion coverage.

Prochoice lawmakers in Congress have also stepped up with legislation of their own. Last fall, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Rep. Judy Chu (D-CA), along with 30 original cosponsors in the Senate and 58 in the House, introduced the Women’s Health Protection Act, the first major proactive abortion rights legislation to be introduced in Congress in many years. The bill would invalidate TRAP laws and overturn restrictions on medication abortion that make it more difficult for women to access early abortion. The bill would also outlaw previability abortion bans and prohibitions on medical training specifically for abortion. In addition, it would invalidate any laws that require women to make separate visits to clinics prior to receiving abortion care for reasons unrelated to medical necessity, be it state-dictated counseling or mandatory ultrasounds. The main beneficiaries of the Women’s Health Protection Act, were it to pass, would be young and poor women and women of color, who bear the brunt of the very laws that the bill would invalidate.

Undoubtedly, recapturing momentum not only in defense of abortion rights but in support of a proactive abortion rights agenda will be slow and challenging. What has only just begun represents a good start, however, and it is a good time to start. That is because as the politics rage on, women will continue to need quality and compassionate abortion care.