Since its inception in 1970, the Title X national family planning program has guaranteed confidentiality for all patients receiving its services—including adolescents. Such protections are well grounded in medical and ethical standards and reflect research demonstrating that without access to confidential care, many adolescents would not seek needed health services. Still, socially conservative policymakers and advocates have long sought to undermine the ability of minors to obtain confidential sexual and reproductive health care, based on the premise that the very availability of confidential services promotes sexual activity among young people, undermines parental authority and interferes with parent-child relationships.

Historically, attempts to keep minors from confidentially accessing contraceptive, STI and other preventive family planning services under the program have largely failed. Despite the previous failures of these attacks and considerable evidence of their potential harm, social conservatives have never given up the fight. Now, the Trump administration is poised to undermine confidentiality protections in the Title X program, threatening adolescents’ access to needed family planning services nationwide.

Title X’s Confidentiality Standards

For nearly 50 years, the Title X program has provided affordable and confidential contraceptive, STI and related family planning care to people regardless of age. The Title X statute recognizes the important role that parents and guardians play in many young people’s lives, calling on providers to encourage familial involvement in patients’ decision making "to the extent practicable," but stopping short of requiring minors to notify or obtain consent from their parents or guardians. Moreover, long-standing program regulations require that Title X‒supported providers guarantee confidentiality for all clients, including minors.1 This was most recently affirmed in a 2014 program policy notice stating that Title X providers "may not require written consent of parents or guardians for the provision of services to minors. Nor can Title X project staff notify a parent or guardian before or after a minor has requested and/or received Title X family planning services."2

Adolescent patients’ confidentiality is also addressed in a comprehensive set of clinical recommendations for the provision of high-quality family planning care to which Title X providers are expected to adhere. These national, evidence-based "quality family planning" guidelines were established in 2014 by the Office of Population Affairs (OPA), which administers the Title X program, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.3 In keeping with Title X provisions, the guidelines advise that providers should "encourage and promote communication between the adolescent and his or her parent(s) or guardian(s) about sexual and reproductive health," by supporting both adolescents and adults in such conversations. The guidelines also specifically state: "Confidentiality is critical for adolescents and can greatly influence their willingness to access and use services."

One exception to the program’s standard of confidentiality is that federal law has long required Title X providers to comply with any state laws requiring notification or reporting of child abuse, child molestation, sexual abuse, rape and incest. That requirement reinforces the obligations that clinicians already have to make reports in compliance with state and local reporting laws (as do many other professionals who have frequent contact with young people). Appropriately, states and localities are charged with determining providers’ compliance with these laws.

Medical and Ethical Standards

Title X’s confidentiality protections also reflect evidence-based recommendations of many leading professional medical organizations. Those recommendations both encourage adolescents to include a parent or guardian in decisions about their medical care as appropriate, while at the same time clearly establishing that minors must be able to obtain care without familial involvement.

In a 2017 committee opinion on contraceptive counseling for adolescents, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) affirmed the importance of discussing sexual and reproductive health with young people.4 ACOG advises a first reproductive health visit sometime between age 13 and 15 that "should encompass a discussion about contraception and STIs in addition to preventive medicine services such as human papillomavirus vaccination." ACOG also makes clear: "Confidentiality is an essential component of health care for all patients. It is even more crucial for adolescents because the lack of confidentiality can be a barrier to the delivery of reproductive health care services." ACOG also promotes the use of online patient portals to engage young people in their own care and "to provide age-appropriate venues for confidential communication." Moreover, if a clinician cannot implement necessary safeguards in their insurance billing, electronic health records or other recordkeeping systems to guarantee adolescents’ confidentiality, ACOG suggests providers refer these patients to a Title X‒supported site for contraceptive services.4,5

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) echoes many of these directives. In a 2014 report on providing contraceptive care to adolescents, AAP states: "In the setting of contraception and sexual health care…policies supporting adolescent consent and protecting adolescent confidentiality are in the best interests of adolescents."6 The report recognizes the body of scientific evidence that supports this view in urging clinicians to pay "careful attention to minor consent and confidentiality," particularly in obtaining sexual histories and helping adolescents to select and continue using methods of contraception. AAP also emphasizes that adolescents are able to understand and respond appropriately to the kind of "complex messages" conveyed in comprehensive conversations between a clinician and patient about sexual and reproductive health.

Other major medical associations—including the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM)—encourage conversations with parents or guardians in most cases, but make clear that, when state law does not require otherwise, such disclosure should not be mandated in order not to force minors into forgoing care.7,8 Both the AMA and SAHM also recognize that understanding and consenting to services without familial involvement is a standard of care commensurate with most adolescents’ maturity and self-sufficiency.

Promoting Adolescents’ Access to Care

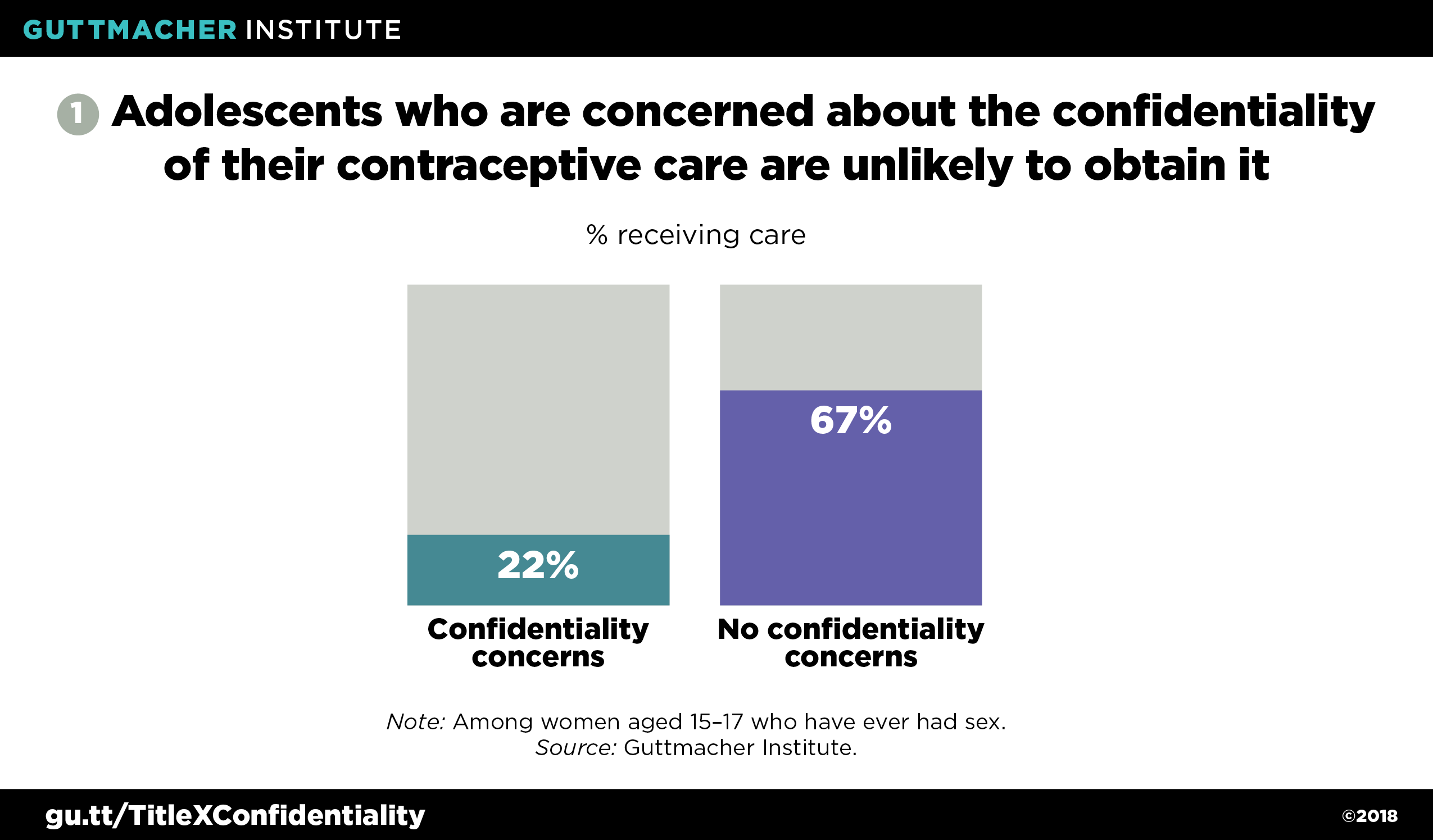

Protections for adolescent confidentiality in sexual and reproductive health care—as provided for under Title X and supported by major medical associations—are also backed by research suggesting that undermining these protections would likely have harmful consequences. Specifically, considerable evidence shows that many young people would forgo contraceptive and STI services if they could not obtain such care confidentially, while remaining sexually active and therefore at greater risk for negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes. One recent nationally representative analysis found that among all female adolescents aged 15‒17, a considerable minority (19%) said they would not seek sexual or reproductive health services if their parents or guardians might find out.9 Among young women aged 15‒17 who had ever had sex, only 22% of those who expressed confidentiality concerns received contraceptive counseling or services in the previous year, compared with 67% of those who did not report such concerns (see figure 1).9 This suggests that the guarantee of confidentiality is critical for many young women to obtain the methods of contraception that work best for them.

Similarly, a different analysis of nationally representative data from 2013‒2015 found that among all female adolescents aged 15‒17 (including those who have never had sex), 20% of those with confidentiality concerns had obtained any sexual or reproductive health services in the previous year (including contraceptive care, STI testing, Pap tests and pelvic exams), compared to 34% of those without concerns.10 Another national study from 2005 of women younger than 18 who were obtaining care from publicly funded family planning centers found that among those whose parents or guardians were not aware of their visit, only 30% said they would continue to visit that provider for prescription contraceptives if familial involvement were mandated.11 In this same study, only 1% of respondents said their sole reaction to being forced to involve a parent or guardian would be to stop having sex. Moreover, a number of site- and school-based surveys of adolescents have demonstrated young people’s willingness to delay or forgo contraceptive care or STI testing and treatment if they thought parents or guardians might find out.12–14

Furthermore, a 2016 nationally representative study of Title X clients found that among those younger than 20 who had health insurance, just over half did not plan to use that coverage for their visit because of confidentiality concerns.15 In this situation, providers can rely on Title X grant funds to help defray the cost of providing care to those patients without reimbursement from the patient’s insurance plan.

Past Threats Return

Many social conservatives have never accepted that adolescents should be able to have confidential access to sexual and reproductive health services, and have repeatedly attempted to undermine or eliminate Title X’s protections. Their most prominent attempt to date was in 1982, when the Reagan administration sought to obstruct minors’ access to confidential Title X‒supported services in a number of ways, including by requiring that providers notify a parent or guardian within 10 days after a minor obtained contraceptive services—a proposal commonly referred to as the "squeal rule." The rule was struck down the following year and never went into effect; several courts determined it undermined the intent of Title X to help adolescents avoid unintended pregnancy, and therefore subverted congressional intent.16 One federal court noted that in enacting the Title X statute, Congress’s intent was "crystal-clear and unequivocal" in that it "did not intend to mandate family involvement."17

In the years since, Title X’s provisions have also effectively superseded states’ attempts to restrict minors’ access to confidential care. For instance a 1997 federal court decision, which the U.S. Supreme Court let stand, determined Title X’s confidentiality protections took precedence over a Missouri state law requiring a parent or guardian to consent for a minor to obtain contraceptive care.18 Two states, Texas and Utah, prohibit the use of state funds to provide contraceptive care to minors without the consent of a parent or guardian; in both states, those restrictions are not applicable to Title X–supported services.19

Now, Title X’s confidentiality protections are once again in jeopardy. The politically appointed leaders of OPA under the Trump administration have consistently demonstrated antipathy toward adolescents’ ability to make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive health. With this leadership, the administration has been moving to undermine Title X’s confidentiality protections while at the same time prioritizing familial involvement.

OPA leadership first advanced their agenda in a February 2018 call for entities to apply for Title X services grants.20 That announcement made it a formal program priority for clinicians to encourage adolescents to involve parents or guardians, while simultaneously and conspicuously not once mentioning the importance of confidential care. The funding announcement also called on providers to "subject" any Title X client younger than 18 who has an STI or is pregnant to "preliminary screening to rule out victimization." This represents a step far beyond clinicians’ obligations to report suspected abuse and assault, demonstrating distrust in providers’ professional judgment and stigmatizing sexually active minors.

The Trump administration took additional steps in June 2018, proposing a set of sweeping changes to the federal regulations that govern the Title X program.21 Under this proposal, clinicians would have to document their efforts to encourage all Title X patients who are minors to involve parents or guardians in their decision making—or document why such participation was not encouraged. It appears patients younger than 18 would not be able to obtain Title X−supported services without such documentation.22 The proposed rule would also codify the February 2018 funding announcement’s demands that providers treat all pregnant minors or those with STIs as potential victims of abuse. Notably, as of early November, the Trump administration has yet to finalize these changes to the Title X program, as it is reviewing and accounting for tens of thousands of public comments on its proposal.

Rationalizing Attacks on Confidentiality

Proponents of mandated familial involvement, such as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops23 and the Susan B. Anthony List,24 have offered multiple rationales for opposing government policies giving minors the right to consent to sexual and reproductive health services without their parents’ knowledge. None of them hold up to scrutiny.

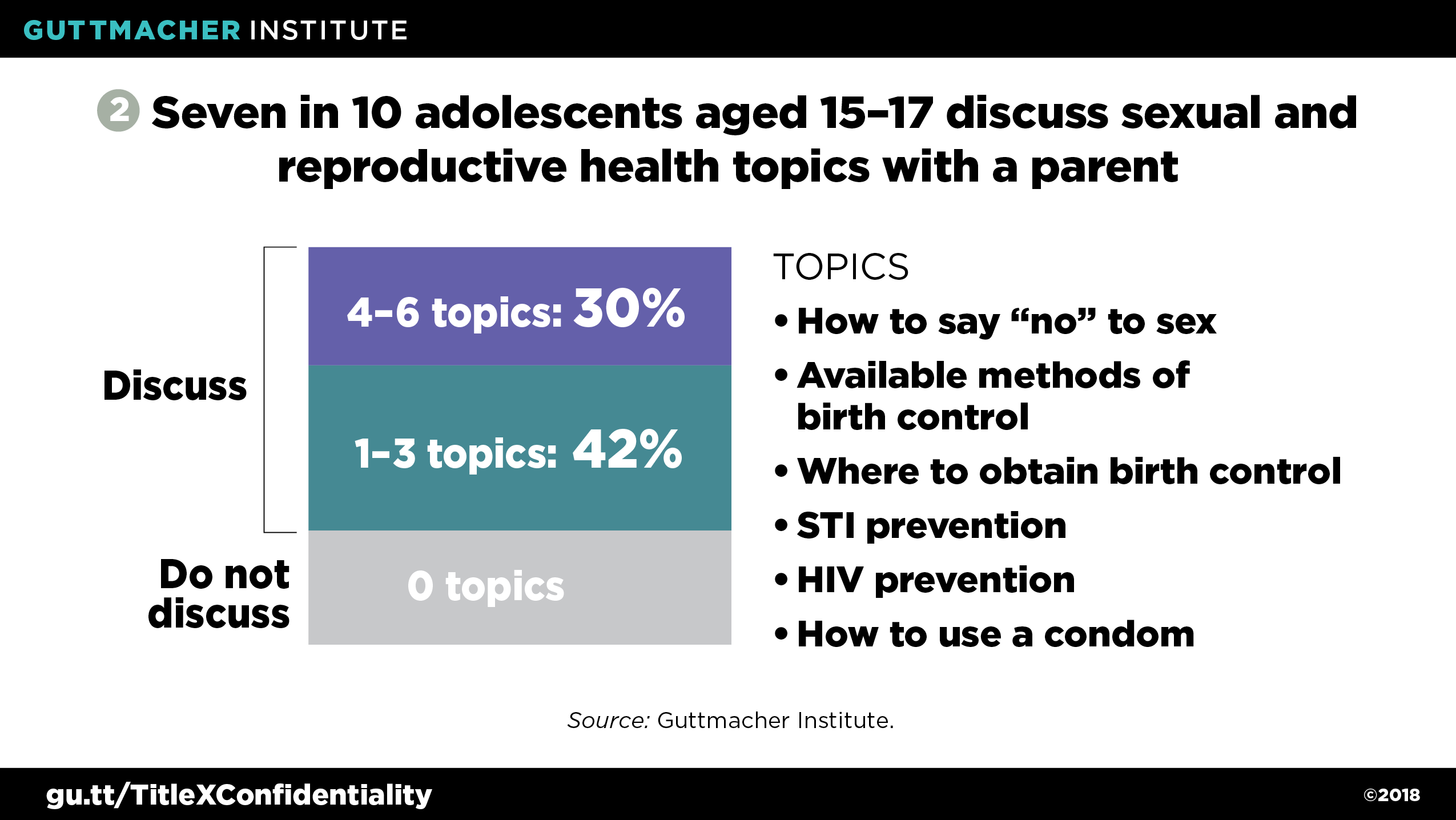

First, social conservatives often argue that confidential services undermine parental authority and family values, and that requiring parental involvement is necessary to strengthen communication between young people and parents or guardians. In reality, research suggests that mandates are not necessary to promote communication, as most adolescents already talk to a parent or guardian about sexual and reproductive health issues. For example, a recent nationally representative study found that seven in 10 of all adolescents aged 15–17 reported having discussed at least one topic related to sexual and reproductive health with a parent or guardian; 30% had discussed at least four topics (see figure 2).9 These findings bolster a 2005 national study of women younger than 18 who were clients at publicly funded family planning centers; the study found that six in 10 of these patients reported that a parent or guardian knew they were there for contraceptive services, and in many cases had suggested the visit.11

The assertion that mandates are the only way to ensure young people engage their parents or guardians in family planning decision making does nothing to help adolescents or adults. For the majority of minors who already involve a family member in their care, a legal mandate to do so is clearly not the motivating factor. Rather, open communication is often fostered by adults’ own attitudes toward and engagement with their children.25 For the many young people who do not feel they can talk with their parents or guardians—often out of fear that they will face some type of punishment or abuse for being sexually active—confidentiality protections are essential. This reality can be particularly pronounced among marginalized adolescents, such as those who are experiencing homelessness, identify as LGBTQ or are in the foster care system.26 Requiring familial involvement in such cases would have real potential for harm, by either triggering some form of punishment or forcing adolescents to forgo needed care.

A second common argument by social conservatives is that confidential sexual and reproductive health care promotes sex and pregnancy among adolescents. Yet, the evidence belies that assertion. Over the past several decades—during which Title X’s confidentiality protections were in place—adolescent pregnancy rates have declined precipitously. These declines have been driven almost entirely by adolescents’ improved contraceptive use—including using more effective methods, using methods more consistently, and using more than one method at once.27–29 At the same time, the proportion of U.S. high school students who have ever had sexual intercourse has fallen to an all-time low, suggesting that access to and use of contraceptives is not tied to increases in adolescent sexual activity.30 Similarly, while several studies of school-based health centers that provide contraceptive methods have shown contraceptive availability increases students’ use of contraception, other studies have not found any associated increases in sexual activity.31–33

Finally, proponents of mandated familial involvement have often attempted to capitalize on the reporting of abuse or rape and related legal protections for young people. This argument dates back to the mid-1990s and alleges that family planning providers use confidentiality as a "shield" to withhold information from parents and guardians, and to keep state and local authorities from taking action to protect young people’s well-being.34 State laws criminalize sexual activity (including rape and other nonconsensual acts) with a minor, though state laws vary with regards to the age of consent, the permissible age difference between two individuals and the type of sexual activity that constitutes a crime. A separate body of state laws requires individuals who often work with young people, including health care providers, to report when they suspect an individual under the age of consent has been sexually abused. Proponents of mandated familial involvement seek to not only vigorously enforce existing mandatory reporting laws, but also to significantly expand reporting requirements, forcing clinicians to report cases of sexual activity well beyond those they believe, in their professional judgment, are truly harmful, coercive or exploitive. The Trump administration is revitalizing this flawed rationale through its requirement that every adolescent obtaining care from a Title X‒supported provider who is pregnant or has an STI must be subject to additional screening.

Such expanded reporting stands to undermine, rather than support, efforts to protect young people, in part by unnecessarily burdening authorities. For instance, in 2003, Kansas officials moved to interpret state law as requiring providers to report all sexual activity—including consensual behaviors between two young people—among adolescents younger than 16.35 This mandate extended to reporting all adolescents seeking contraception, STI services, a pregnancy test or abortion care, as well as those who even discussed kissing or other sexual contact in the context of a health care visit. The state’s extreme interpretation of its law was struck down by a federal judge, who ruled it would hurt adolescents and generate overwhelming reporting demands on officials.36 Recognizing its harm, the Kansas legislature subsequently clarified that state law did not mandate such an intrusive and unnecessary level of reporting.

Pushing Back, Protecting Adolescents

As previous attempts to mandate familial involvement have been rejected by clinicians, advocates, courts, researchers and adolescents themselves, so too should current and any future efforts. Many adolescents proactively involve their parents or guardians in their sexual and reproductive health decision making. For others who may not be able to involve their parents—for whatever reason—family planning providers are seen as trusted adults and mandated familial involvement in that relationship would drive those adolescents away from needed care. For these young people, the Title X program and its confidentiality protections are essential. Policymakers should be working with—not against—family planning providers to ensure young people can consistently obtain patient-centered care that meets their individual needs and promotes their sexual and reproductive health, rights and dignity.