Among the many health policy advances of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the requirement that most private health plans nationwide include coverage of contraceptive methods and services. This federal contraceptive coverage guarantee builds on earlier coverage policies in more than half the states,1 as well as a groundbreaking ruling in December 2000 by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission stating that denying coverage for contraception in a health plan that covers other preventive services and prescription drugs amounts to sex discrimination.2

The ACA’s guarantee went further than earlier policies by being enforceable nationwide and by including several key requirements for private health plans: Plans must cover 18 specific contraceptive methods; eliminate out-of-pocket costs, such as copayments or deductibles; and limit other barriers, such as prior authorization requirements. More than 55 million adult women had this coverage as of 2015, according to government estimates.3

The guarantee was reaffirmed in December 2016 by the federal government, on the recommendation of a panel of health professional organizations and consumer advocacy groups, led by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.4 Yet, with the 2016 elections expanding the power of social conservatives under the Trump administration and the 115th Congress, the contraceptive coverage guarantee is now in danger.

Citing ongoing legal challenges to the guarantee, some conservative policymakers and advocates are calling for a sweeping exemption for any employers that have religious or moral objections to including some or all contraceptive methods in the health plans they sponsor for employees and dependents. Others are calling for the outright elimination of the contraceptive coverage guarantee.

The Trump administration will have the authority to take either approach, quickly and without the assistance or assent of Congress. And Congress could also pass a broad religious exemption or eliminate the guarantee, in free-standing legislation or as part of a repeal of the ACA. Either type of roll-back would be harmful to women and families, for several key reasons.

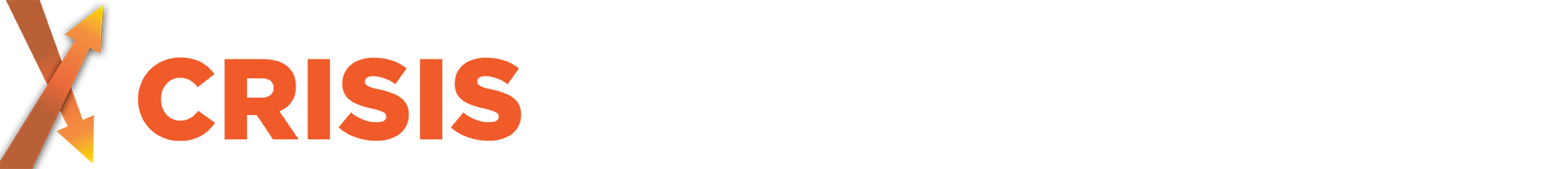

Contraceptive use benefits women and families. Contraceptive use helps enable women and couples to prevent unwanted pregnancies and to plan and space those they do want. That, in turn, has real health benefits. Spacing pregnancies reduces the risk of premature birth or low birth weight.5 Preventing unintended pregnancy can help women manage some health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, and avoid a risk factor for depression.6–8 And according to numerous studies, contraceptive use enables women to complete their education, get and keep a good job, support themselves and their families financially, and invest in their children’s future (see chart 1).9,10

Contraceptive choice facilitates effective use. Women’s contraceptive needs and choices are influenced by the relative effectiveness of contraceptive methods; concerns about side effects, drug interactions and hormones; how frequently they expect to have sex; their perceived risk of STIs; their desire for confidentiality and control; and a host of other factors. American women use an average of three or four methods by age 40, choosing among their options to find the methods that best fit their needs at any given time.11

Women who are not satisfied with their choice of a method are particularly likely to use it inconsistently or incorrectly, or to experience gaps in use.12 And consistent use matters: The two-thirds of women at risk for unintended pregnancy who consistently and correctly use a method account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.13 For these reasons, women need access to not just any method of contraception, but to the ones most suitable for their individual needs and circumstances.

Cost can be a substantial barrier to contraceptive choice. Highly effective methods—such as IUDs, implants and sterilization—are ultimately cost-effective, but entail high up-front costs. In the absence of the contraceptive coverage guarantee, many women would need to pay more than $1,000 to start using one of these methods—nearly one month’s salary for a woman working full-time at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.14 And even the cost of oral contraceptives, or the contraceptive ring or patch, can add up to a considerable ongoing burden for women. So, it is no surprise that a study conducted prior to the guarantee’s implementation found almost one-third of women said they would switch methods if they did not have to worry about cost.15

The concept of cost as a barrier is by no means unique to contraception. Numerous studies have demonstrated that even seemingly small copayments and other costs can dramatically reduce use of preventive health care, particularly among low-income Americans.16 Removing cost barriers—as the federal policy requires, for contraception and dozens of other effective preventive care services—has been proven to facilitate use of needed care. It also reflects a respect for patient autonomy, allowing women to make choices about contraception without financial coercion.

The contraceptive coverage guarantee is working. Even prior to the ACA, contraceptive coverage requirements were having an impact: Among privately insured women, those living in states with such requirements were more likely to use contraceptives during each sexually active month than those living in states with no such requirement, even when accounting for differences in education and income.17 And the ACA’s coverage guarantee has expanded coverage further while also eliminating out-of-pocket costs.

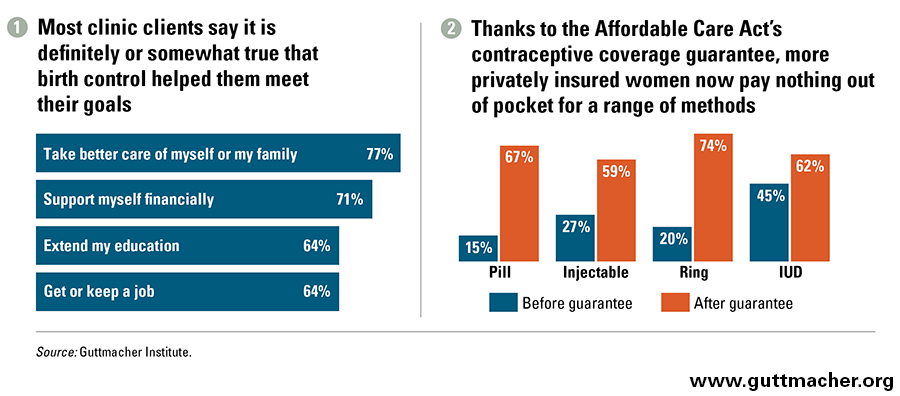

As a result, tens of millions of women now face fewer cost barriers to obtaining contraception. Between fall 2012 and spring 2014 (during which time the coverage guarantee went into wide effect), the proportion of privately insured women who paid nothing out of pocket for the pill increased from 15% to 67%, with similar changes for injectable contraceptives, the vaginal ring and the IUD (see chart 2).18 Another study estimated that pill and IUD users saved an average of about $250 in copayments in 2013 because of the guarantee.19

There is emerging evidence that eliminating cost barriers has had a positive impact on contraceptive use. In one study using claims data from 635,000 privately insured women nationwide, women were less likely to stop using the pill once costs were removed in the wake of the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee.20 Another study using claims data from 30,000 privately insured women in the Midwest found that the reduction in cost sharing because of the guarantee was tied to a significant increase in the use of prescription methods; that increase came disproportionately from women choosing long-acting methods.21 By facilitating women’s ability to choose a contraceptive method and use it consistently, the guarantee is helping them to plan whether and when to become pregnant and to secure the health, social and economic benefits that follow.

Taking away the coverage guarantee would do serious harm. For all these reasons, it would be shortsighted for policymakers to undermine or eliminate the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee and all the benefits that accrue from it. Proposals to fully exempt any employer that objects to coverage would bring harm to tens or hundreds of thousands of U.S. women and their families. These employers’ religious objections are already accommodated by current federal policy that allows them to step away from paying for, arranging for or even talking about contraceptive coverage while still ensuring that employees and their dependents are seamlessly covered without cost sharing. Proposals to eliminate the coverage guarantee entirely are even more extreme: They would harm tens of millions of women and their families. The smarter choice for the country would be to put aside these extreme proposals and instead preserve and expand upon the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee.