Anti–family planning policymakers and advocates often argue that contraception is simple for people to obtain and for clinicians to provide. For example, opponents of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) contraceptive coverage guarantee have argued that the policy is unnecessary because condoms are inexpensive and readily available at drug stores. Some have built on this line of reasoning by suggesting that oral contraceptives should be given over-the-counter status too, as a replacement for comprehensive insurance coverage of contraception.1 Similarly, social conservatives seeking to exclude Planned Parenthood from public programs such as Medicaid have argued that less-specialized health care providers, such as federally qualified health centers, could fill the void this would create.2 And in October, a leaked White House memo recommended that funding for the Title X national family planning program should be cut by at least half and suggested that money could be better used for teaching adolescents about fertility awareness methods exclusively.3

One common problem with all of these arguments is that they overlook a central aspect of quality family planning services: providing patients an informed choice about their options from among a wide array of contraceptive methods. Federal policies and programs have long promoted method choice in order to facilitate effective contraceptive use and to fight potential coercion—and they must continue to do so.

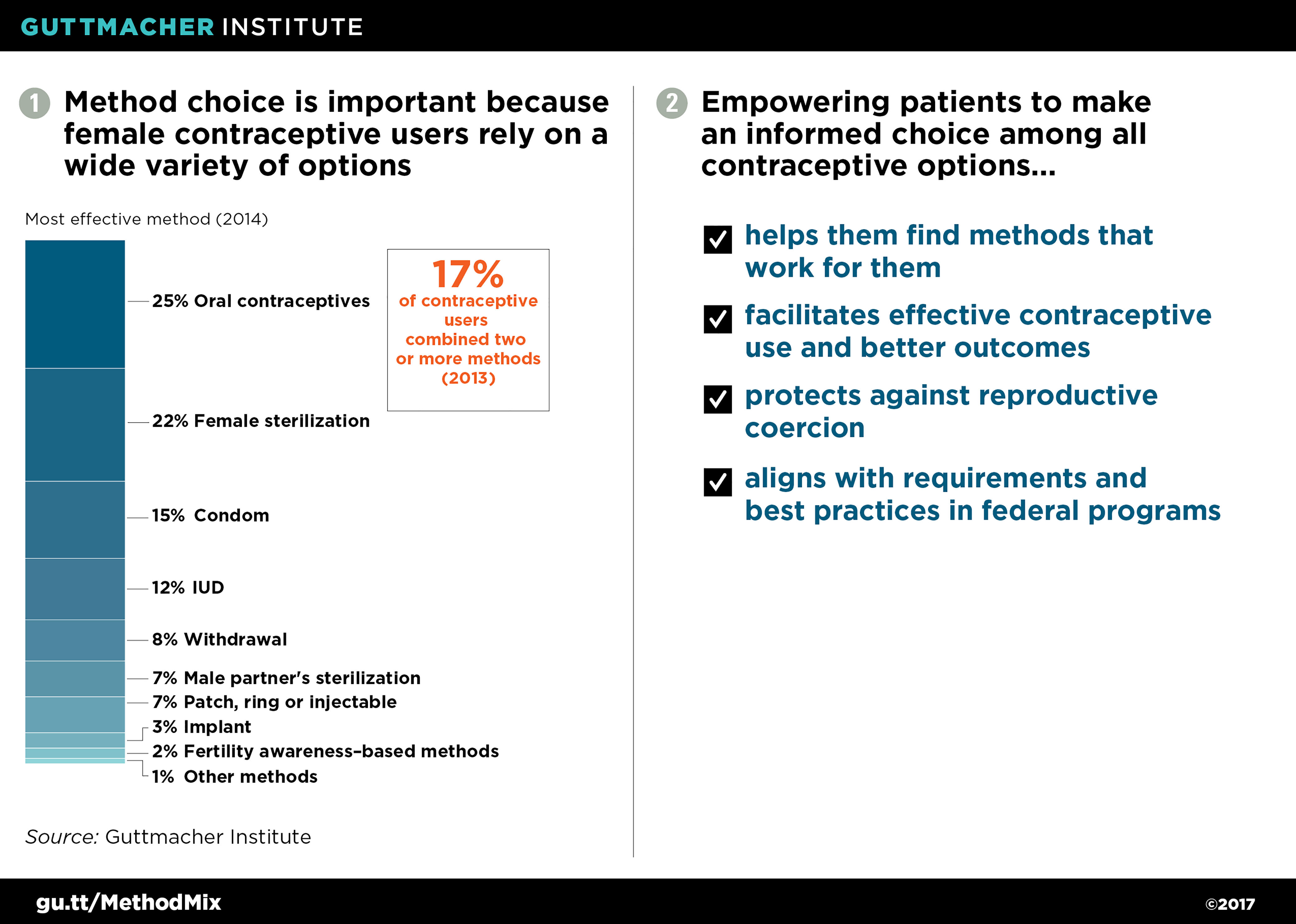

U.S. women and couples rely on a broad mix of contraceptive methods. Despite what some social conservatives appear to believe, oral contraceptives and condoms are not the only contraceptive methods people use. In 2014, 25% of female contraceptive users relied on oral contraceptives and 15% relied on condoms as their most effective method (see figure 1).4,5 That means that six in 10 female contraceptive users relied on other methods: female sterilization or a male partner’s sterilization; hormonal or copper IUDs; hormonal methods including the injectable, the ring, the patch and the implant; and behavioral methods, such as withdrawal and fertility awareness–based methods.

Moreover, most women rely on multiple methods over the course of their reproductive life, with 86% having used three or more methods by their early 40s.6 Sometimes, women and couples may try out different methods to find one that they can use consistently or that minimizes side effects. Other times, they may switch from method to method—such as from condoms to oral contraceptives to sterilization—as their relationships, life circumstances and family goals evolve.

In addition, many people use two or more methods at once: 17% of female contraceptive users did so the last time they had sex.5 For example, they may use condoms to prevent STIs and an IUD for the most reliable prevention of pregnancy. Or they may use multiple methods simultaneously—for instance, condoms, withdrawal and oral contraceptives—to provide extra pregnancy protection.

Informed choice improves effective use and leads to better outcomes. Having access to a wide range of methods is important because contraception is not one size fits all. People choose a method for a host of reasons. One important feature for most women is how well a method works to prevent pregnancy.7 When used perfectly, all methods have low failure rates. But in the real world, the easier a method is to use, the more effective it is. For example, the "set and forget" nature of IUDs and implants leads to considerably lower failure rates, on average, than the rates for condoms (which require consistent use every time a couple has sex) or fertility awareness–based methods (which require careful monitoring of a woman’s cycle).

Beyond effectiveness, there are many other features that people say are important to them when deciding on a method. These include concerns about and past experience with side effects, drug interactions or hormones; affordability and accessibility; how frequently they expect to have sex; their perceived risk of HIV and other STIs; the ability to use the method confidentially or without their partner’s permission; and potential effects on sexual enjoyment and spontaneity.

Women who are satisfied with their current contraceptive methods are less likely to use them inconsistently or incorrectly. For example, 35% of satisfied oral contraceptive users have skipped at least one pill in the past three months, compared with 48% of dissatisfied users.8 Consistent contraceptive use helps women and couples prevent unwanted pregnancies and plan and space those they do want. In fact, the two-thirds of women at risk for unintended pregnancy who consistently and correctly use a method account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.9

Moreover, contraceptive use has a multitude of other health benefits, as well as social and economic benefits. Spacing pregnancies reduces the risk of having a low birth weight or premature birth.10 Preventing unintended pregnancies can help women manage health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and heart disease as well as avoid increased risk for depression.11–13 Contraceptive use also enables women to achieve their own educational and career goals and support themselves and their families financially.14 On top of all of this, every dollar spent on publicly funded family planning services saves $7 in federal and state spending on medical care related to unintended pregnancies.15

Contraceptive choice helps to prevent reproductive coercion. The United States has a long and troubling history of coercive policies and practices around reproductive health, particularly for low-income women and women of color (see "Guarding Against Coercion While Ensuring Access: A Delicate Balance," Summer 2014). Over the decades, government officials, judges and medical professionals have engaged in unjust practices including forced sterilization of women deemed "unfit" to have children, offers of financial incentives to welfare recipients who use long-term or permanent contraception, and reductions in jail time for offenders who agree to use contraception. And recently, the rising popularity of IUDs and implants—methods that are long-acting and highly effective—have sparked concerns that excitement around the methods could take a turn toward coercion if policymakers or providers try to incentivize their use.16,17

Offering an unrestrained choice of contraceptive methods—or the choice to use no method at all—is essential to guarding against coercion. But doing so effectively requires considerable resources and expertise from providers. People must be given all the information they need to decide which contraceptive methods might best meet their goals and preferences at any point in their lives. They must be offered unrestricted and affordable access to the full range of methods and any related medical services. They must be able to stop using a method at any time without financial or other constraints; this is a particularly important requirement for IUDs and implants, since those devices must be removed by a medical professional. And they must be offered contraceptive care that meets the highest quality standards and that is culturally and linguistically appropriate, to help counter societal and provider biases that might be coercive in a more subtle manner.

This connection between informed contraceptive choice and protecting against reproductive coercion is explicitly recognized in federal family planning policies. For example, the Title X family planning program regulations bar "any coercion to accept services or to employ or not to employ any particular methods of family planning."18 Medicaid is similarly explicit in linking the two concepts, requiring that enrollees must be "free from coercion or mental pressure and free to choose the method of family planning to be used."19

Federal programs have long promoted contraceptive choice and must do even more. In order to facilitate effective contraceptive use and guard against coercion, federal family planning policies and recommendations include multiple protections to ensure that patients can make informed contraceptive choices. At the most basic level, these policies call for covering or offering a wide range of methods. That practice has long been the norm in Title X and Medicaid, and the ACA expanded on this concept by requiring most private insurance plans to cover 18 distinct contraceptive methods used by women.20

Moreover, federal policies eliminate or minimize patients’ out-of-pocket costs for contraceptives, helping to mute financial pressures on method choice. For decades, Medicaid has barred cost sharing for family planning, and the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement does the same. And Title X and other safety-net family planning programs are required to provide free or reduced-cost services for low-income clients.

In addition, Medicaid and the ACA prohibit or discourage many of the common insurer restrictions and practices that interfere with contraceptive choice.21–23 These include prior authorization in order to cover specific methods, step therapy (requiring that a patient try and fail with one method before trying the method of her choice), policies that restrict IUD or implant removal or other changes in method use, and inappropriate quantity limits (such as covering only one IUD every five years, even if a previous device was expelled or removed for a planned pregnancy).

Federal recommendations that set the standard of care for quality family planning services encourage numerous practices that expand method choice and accessibility.24 That includes providing patient-centered counseling about the full range of contraceptive options, offering on-site provision of methods (rather than by prescription or referral), offering same-day insertion of IUDs and implants, using "quick start" protocols to initiate contraceptive use immediately (regardless of where a woman is in her menstrual cycle), dispensing a full year’s supply of a method at one time, and forgoing unnecessary examinations and tests. Government programs have also taken steps to address supply-side barriers to method choice, such as by helping providers secure training in new or emerging contraceptive methods and working to reduce the cost of keeping methods in stock.

Federal and state policies must build on, not undermine, this strong foundation of contraceptive choice. That means buttressing existing federal protections at the state level to ensure that anti–family planning activists and policymakers, including those in the Trump administration, do not undermine Medicaid, private insurance or family planning grant programs.22,23,25 And it means expanding on current protections in various ways: For example, policymakers could address gaps in insurance coverage by requiring Medicaid and private insurance plans to cover vasectomy and condoms, as well as methods obtained without a prescription. Expanding the opportunities for all people to make their own free and informed choices about contraception would have clear health, social and economic benefits, and is simply a moral imperative.