Federal and state policymakers and advocates continue to debate what the future of the U.S. health care system will look like. Nearly a decade after it was enacted, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) remains under attack by conservative policymakers and in the courts. Meanwhile, progressive policymakers and advocates are eager to build on or even replace the ACA in order to address problems such as persistent coverage gaps and high out-of-pocket costs for patients. One approach would be incremental, such as establishing a "public option" to allow people to "buy in" to a publicly funded program like Medicaid or Medicare as a form of competition with private insurance plans. The second main approach would be a comprehensive overhaul of the existing health care system; some versions of this approach, often described as "Medicare for All," would move most or all U.S. residents to government-run coverage.

Whatever approach policymakers take, it is imperative that they fully address the wide array of sexual and reproductive health needs. The continued political and legal fights over the ACA have demonstrated that social conservatives will take every opportunity to undermine provisions that protect and promote sexual and reproductive health and rights.1,2 The best defense against such attacks is specific and detailed statutory language, which can help guide implementation and is more difficult to undermine or reinterpret through federal or state agency regulations and guidance.

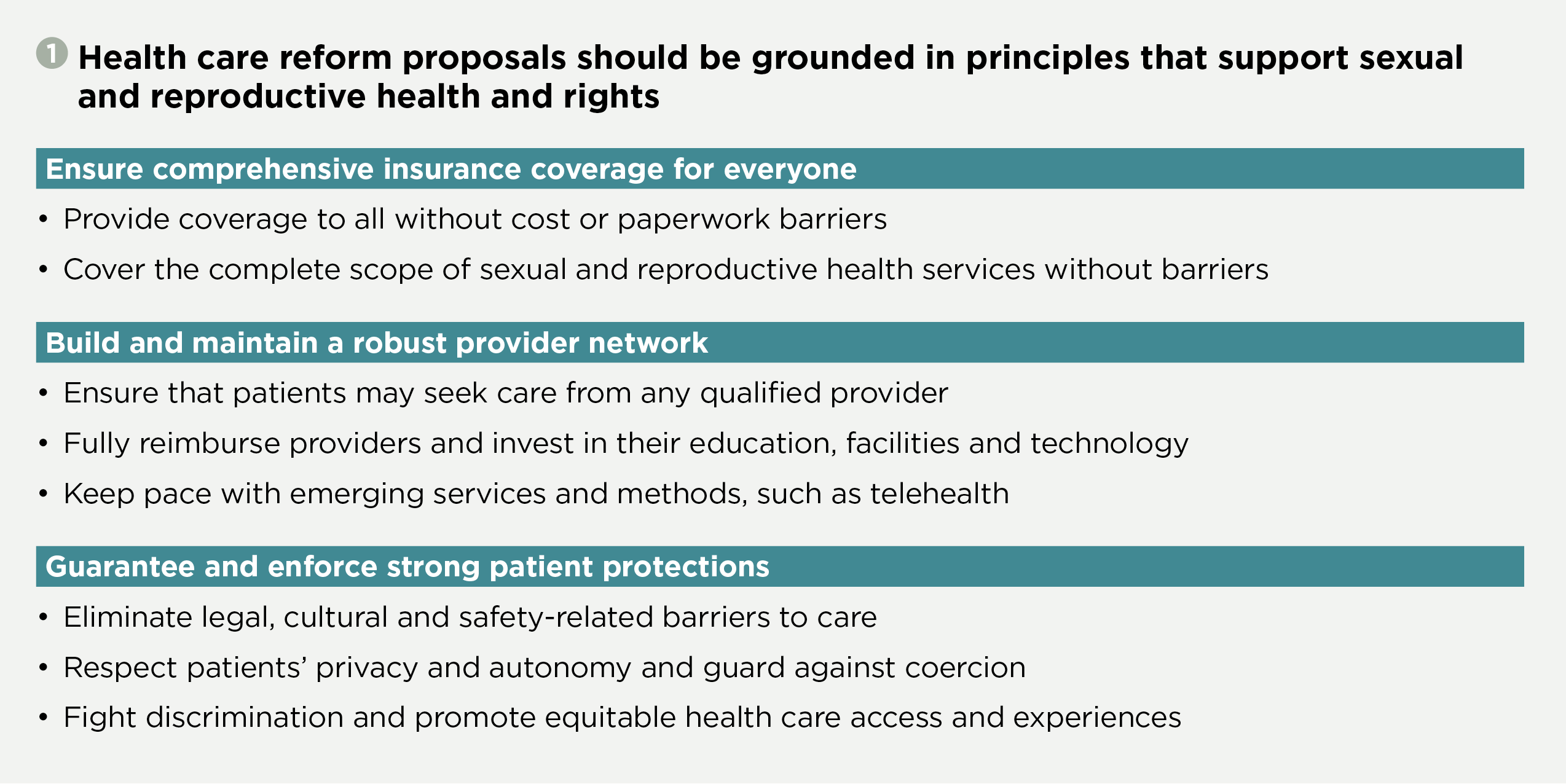

To develop effective statutory language, policymakers will need a roadmap—a clear set of specific principles for how to ensure that everyone has comprehensive coverage for sexual and reproductive health services; has unrestricted access to a robust network of providers; and can rely on a wide array of patient protections (see figure 1).

Comprehensive Coverage for Everyone

One overarching goal for any health care reform proposal is that coverage should be comprehensive. That means coverage for all of the services people need, without financial or other barriers.

Eligibility. Under the current, patchwork system, people face daunting inequities in coverage based on income, employment, age, immigration status, race and ethnicity, and many other factors.3,4 Further health care reform presents an opportunity to eliminate those inequities and ensure that everyone in the United States (not just citizens, for example) has health coverage.

In order to achieve this, coverage should be affordable for everyone so that costs are never a barrier to becoming or staying enrolled.5 That might mean eliminating premiums entirely and paying for coverage through progressive taxation, or it might mean setting premiums on a sliding scale and supporting them with progressive subsidies.

Red tape should be eliminated as a coverage barrier, too, by minimizing or eliminating renewal, documentation and other paperwork requirements that often trip up enrollees. And being enrolled in coverage should never threaten people in other ways, such as by endangering their immigration status.6

Services covered. Having health insurance does not mean much unless it pays for the services that a patient needs. People have a wide array of sexual and reproductive health needs, including for services related to contraception, abortion, maternal and newborn health, infertility, reproductive cancers, sexual and intimate partner violence, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), gender affirmation, sexual pleasure and dysfunction, and more (see "More to Be Done: Individuals’ Needs for Sexual and Reproductive Health Coverage and Care," 2019).

Within these areas of care, patients need coverage for information and counseling, prescription and over-the-counter medications, vaccinations (such as for human papillomavirus, or HPV), medical devices and their insertion and removal (such as IUDs and contraceptive implants), medical and surgical procedures (such as sterilization, assisted reproductive technology and radiation to treat reproductive cancers), follow-up care and referrals.7 Many people also need support services, such as transportation, language translation and interpretation, education to improve medical literacy, and home assistance (such as for cancer patients).

Cost should never be a barrier to using one’s health coverage for medical services.5 That might mean eliminating out-of-pocket costs entirely, as the ACA has done already for contraceptive care, STI and cervical cancer screenings, and other preventive services.8 Alternatively, it might mean using sliding fee scales and progressive subsidies, as many public health programs (such as the Title X national family planning program) have long done.

Similarly, patients should not face bureaucratic barriers to needed care, such as prior authorization requirements, step therapy (requiring a patient to try a less expensive alternative before getting access to their preferred option), or medically inappropriate quantity or frequency limits (such as limits that prevent patients from receiving a full year’s supply of contraceptive pills). Eliminating financial and bureaucratic barriers and their potentially coercive effects is particularly important for low-income people, people of color, incarcerated people and people who are disabled, given the nation’s long history of reproductive coercion against these populations.9

More broadly, covered services should be fully available to all, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation or any other patient characteristic. For example, transgender or gender-nonconforming individuals should have full coverage for any sexual and reproductive health services they need—a principle that insurance companies today sometimes fail to uphold, either for discriminatory reasons or out of neglect.10

Robust Network of Providers

A second top-level goal for any health care reform proposal should be to ensure that patients have ready access to a strong network of qualified providers.11 Meeting this goal means allowing patients to visit the providers they choose, investing in a network of providers who can fully meet patients’ needs, and keeping pace with new technologies and opportunities to provide care. This is all particularly important for sexual and reproductive health care and other sensitive services, where patients’ trust in and comfort with their providers is integral to quality of care.

Choice of providers. In order to fully meet patients’ needs, health coverage should allow patients to receive care from any qualified and willing medical provider, rather than the often-narrow networks of providers that many insurance plans use today. These networks should include not just the primary care providers, specialists, health centers, hospitals and pharmacies that policymakers never forget to include in health care reform proposals, but also providers that focus more specifically on aspects of sexual and reproductive health, such as abortion clinics, family planning providers, infertility specialists, STI clinics, midwives and birthing centers. This broader focus would be in keeping, for example, with a long-standing federal Medicaid requirement that enrollees have unrestricted access to the qualified family planning provider of their choice.12

Determining who is considered "qualified" should not be determined by politics or ideology. Rather, qualified providers are those who adhere to the basic rules of medicine: They receive proper training, follow evidence-based medical standards of care developed by major medical associations and government agencies, obtain informed consent for patient care, are transparent and honest about the services they offer, provide referrals elsewhere when needed, and treat their patients in a respectful, noncoercive and nondiscriminatory manner.

Patients should be able to visit a provider for all services the provider is qualified to offer. For example, advanced practice clinicians and nonclinician counselors are key providers for many family planning clinics today, but not all insurance plans reimburse for their services.13 Moreover, many plans today unnecessarily require patients to receive a referral from a primary care provider before visiting a specialist. Several federal and state laws already allow patients to directly access obstetrical and gynecologic care without a referral, and that principle should be applied for all sexual and reproductive health services and providers in all jurisdictions.

Investment in providers. Having the option to choose among medical providers does not mean much if there are not enough providers available to meet patients’ needs. For that reason, any comprehensive health care reform proposal should provide the financial investments needed to maintain and expand the network of qualified providers across the United States.

On the most basic level, that means providing adequate payment to fully reimburse providers for their services, including time spent with patients and time spent coordinating care.14 Reform efforts will, of course, continue to test ways to discourage overprovision, protect against fraud, and otherwise control unnecessary costs, but that should never interfere with patients’ ability to receive the care they want and need and providers’ ability to offer it.

Reform efforts should also invest in individual clinicians. Many areas of the United States have shortages of qualified providers—including abortion providers15 and other reproductive health specialists16—that can be addressed through funding for medical education and ongoing training, and incentives for clinicians to work in underserved areas. Such strategies can also help to diversify the clinician workforce and ultimately make clinics more welcoming for patients. Investments are also needed to offer ongoing training to clinicians on linguistic and cultural competency,17 trauma-informed care,18 identifying and addressing biases, making use of new technologies, and other advances in the health care field.

Beyond the providers themselves, reform proposals should also invest in health care facilities, technology and outreach.19 Appropriate investments include resources for facility infrastructure; electronic health records and other computer- and phone-based technology; quality assessment and improvement efforts; appropriate stocking levels of contraceptives and other supplies; outreach materials and campaigns; and staff training and retention, including for nonclinician staff like community health workers.

Finally, health care reform should specifically invest in safety-net providers, such as family planning clinics, STI clinics, federally qualified health centers and county health departments, that have long been integral to offering sexual and reproductive health care to low-income patients and other marginalized populations. Currently, these providers are supported by a range of targeted programs—such as Title X, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, the National Health Service Corps and many others—that might be subsumed under a comprehensive reform proposal. If that happens, the new system would need to replace those current funds, and expand on them, in order to ensure greater access in rural and other underserved communities.

Emerging services and providers. Any health care reform proposal should build in mechanisms to keep up with technological advances, such as by providing full coverage for new ways patients can access care. Telehealth is an obvious example: It has been widely hailed as a way to address a range of access barriers for patients, such as provider shortages, lack of transportation and child care, long travel distances, privacy concerns and inflexible work schedules.20 When it comes to sexual and reproductive health, telehealth is becoming particularly valuable for the provision of medication abortion and many contraceptive services.21,22

Similarly, health coverage should embrace the national trend toward accessing care at pharmacies, retail clinics and online. That includes paying for contraceptives and other medications—as well as any related counseling or services—when prescribed by a pharmacist, purchased over the counter without a prescription or obtained online. In addition, coverage should be included for HPV and other vaccinations provided at pharmacies or retail clinics; drugs for STI treatment prescribed for a patient’s partner (a practice known as expedited partner therapy, which insurance plans often do not cover);23 and counseling offered outside of a health care visit, such as support for self-managed abortion obtained by phone, online or via a mobile phone application.

Strong Patient Protections

The principle that patients always come first should underlie any health care reform effort. Health care is for the benefit of individuals’ own health and well-being; any benefits to society are secondary. Upholding this principle requires a wide array of patient protections to ensure that the interests of government agencies, health insurance plans, health care providers, taxpayers and other parties never come at the expense of patients.11

Eliminate barriers to care. Eliminating every barrier to patient care is probably an impossible goal; nevertheless, it is one that the United States should continually strive to achieve. Currently, U.S. residents face a wide variety of often interrelated barriers—including economic, geographic, cultural, linguistic, educational, legal, bureaucratic, ideological and disability-related barriers—to obtain sexual and reproductive health care.4 Many of these barriers could be addressed through the same steps taken to guarantee comprehensive, universal coverage and a strong network of providers.

Patients also face numerous legal barriers to sexual and reproductive health care that could be addressed directly or indirectly through reform efforts. Current restrictions include state and federal policies targeting abortion patients and providers;24 the prosecution of women for suspected self-managed abortion;25 and legal and bureaucratic barriers that make it harder for transgender patients to obtain care.26

Patients and providers also experience threats to their safety at abortion clinics and other locations that have been targeted by ideological extremists.27 Insurance coverage is meaningless if patients are driven away from clinics by protesters and threats, tricked into visiting sham clinics, or are unable to find care because providers have been harassed and facilities shut down. A related barrier that should be addressed indirectly through health care reform is the stigma that is often directed at patients who need and obtain abortion, care for HIV and other STIs, infertility services, and other types of sexual and reproductive health care.

Respect privacy and autonomy. Health care reform proposals should rededicate the U.S. health care system to guard against coercion and actively facilitate patient autonomy.28 As a starting point, there should be strict guarantees that all patients receive the complete information they need about their health conditions and options so that they can make truly informed decisions about their care. When a clinician is not trained or unwilling to offer a specific option—such as insertion of an IUD or contraceptive implant, or in vitro fertilization—she should actively refer a patient to a willing and able provider.

A related issue is ensuring the U.S. health care system has protections in place at every level to mitigate the impact of health care professionals and institutions refusing to provide information, services or referrals based on their personal religious or moral views. In some cases, refusals of care should not be allowed at all, because the potential for harm is simply too great. Large health care institutions, for example, are often the dominant or only option in a given community and wield considerable influence over local providers and officials, sometimes to the detriment of sexual and reproductive health and rights.29 In other cases, the objections of individual clinicians or staff members can be accommodated by their employer, so long as the employer has procedures in place to ensure seamless patient care and to avoid stigmatizing or deceiving patients.30 What matters most is the impact on patients: No patient should ever be denied information, referral or emergency care or the ability to give fully informed consent to care, and no one should be provided care that violates medical standards.

Patients should also be guaranteed confidentiality. The U.S. health care system has embraced coordinated care and information sharing among providers, and insurers have long adopted policies meant to protect against fraud and abuse that involve detailed notices to policyholders about services rendered and costs incurred. Those are all valuable features and safeguards, but they also have the potential to inadvertently violate patients’ confidentiality. While it is a cornerstone principle of any medical care, confidentiality is especially vital for patients seeking or obtaining care for sexual and reproductive health services that may be stigmatized or sensitive, and it has been a long-standing protection in Title X and other key federal safety-net programs.31,32 Health care reform proposals should find ways to protect confidentiality in a coordinated, systemic manner.

Similarly, the U.S. health care system is increasingly reliant on quality measurement and improvement, but those efforts have not always prioritized patients’ needs. Measures related to pregnancy desires, contraceptive choices, pregnancy outcomes or other reproductive health services and decisions have the potential to be coercive if they are not developed and applied appropriately.33,34 For example, measures that reward clinicians for their patients’ use of highly effective IUDs and contraceptive implants could lead clinicians to inappropriately push these methods on patients. The data collected and analyzed as part of these efforts should be put to use by government agencies, health insurance plans, providers and researchers in ways that prioritize patients’ needs above other goals, such as cost control.

Break down discrimination and inequities. Health care reform efforts should continue the long and difficult process of overcoming biases in the U.S. health care system that contribute to discrimination and inequities. Many of the protections discussed above would be helpful in addressing structural inequalities. For example, ensuring that patients can obtain and use health coverage without financial barriers would help address inequities related to income, wealth and employment. Providing coverage regardless of immigration status, training clinicians on linguistic and cultural competency, and diversifying the health care workforce would help address inequities faced by many people of color and immigrants, in particular.

However, additional steps are clearly needed. Every person and entity in the U.S. health care system should be explicitly barred from discriminating against people on the basis of characteristics such as race, color, national origin, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status, health status or disability, and those protections should be vigorously enforced.35 Moreover, it is not enough to ban discrimination; health care reform efforts should include measures that can foster a more equitable and nondiscriminatory environment.36 For example, clinicians should be better trained to identify and account for their own biases and to correct for them in how they view and treat their patients. Health care data systems should collect and analyze the information needed to identify and address inequities. Patients themselves should be asked about how they experience bias, and be represented in efforts to assess and correct structural discrimination and more explicit discrimination by clinicians and institutions.

Health care reform on its own would not address the broader social and economic factors that affect people’s health and drive systemic discrimination and inequities. Rather, health care reform efforts in the United States should be paired with initiatives to improve people’s economic prospects, their access to high-quality housing and education, the health and safety of their communities, and the fairness of the criminal justice, immigration and political systems, among others.

An Ambitious Agenda

The steps outlined in this article are immensely ambitious, and that is appropriate because so are the goals of health care reform. The sheer scope of these goals necessitates deep and detailed thinking on a wide array of issues. When it comes to fully addressing people’s sexual and reproductive health needs, it is not sufficient for policymakers or health care analysts to promote plans that cover abortion or reproductive health in general terms. Rather, they should account for the complexities of the topic and identify health care reform strategies that are best suited to address them. And advocates who care about sexual and reproductive health and rights should hold policymakers accountable when they put forward proposals that are simply not good enough.

Editor’s note: This article is the second installment in a two-part series on how sexual and reproductive health and rights fit into U.S. health care reform efforts. The other article describes the wide array of sexual and reproductive health needs that the health care system should address.