Health care reform is expected to take center stage again in the U.S. Congress in 2019. Conservatives are continuing their crusade to undermine the Affordable Care Act (ACA), while progressive lawmakers and advocates are bringing forward new ideas to go beyond that law in incremental or comprehensive ways. The changes proposed by both sides would affect actors at all levels of the health care system, including insurance providers, clinicians, pharmacists, hospital employees, health educators and, of course, patients.

Sexual and reproductive health needs are often discounted or ignored by policymakers and advocates in discussions around health care reform. This is not reflective of their importance to broader health issues, but rather an indication of the cultural and political sensitivities around sexuality, reproductive choices and gender inequality. In reality, sexual and reproductive health and rights have far-reaching implications for people’s overall health, and health care reform offers a unique opportunity to address these issues.

The responsibilities of the health care sector in satisfying sexual and reproductive health needs are articulated in a recent report by the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.1 Written by a globally representative, multidisciplinary assembly of experts in sexual and reproductive health, development, and human rights, the report offers a comprehensive explanation of sexual and reproductive health needs and proposes a comprehensive package of essential interventions to meet those needs. The report’s analysis and findings identify the seven major categories of sexual and reproductive health care, as discussed below.

Delineating the Needs

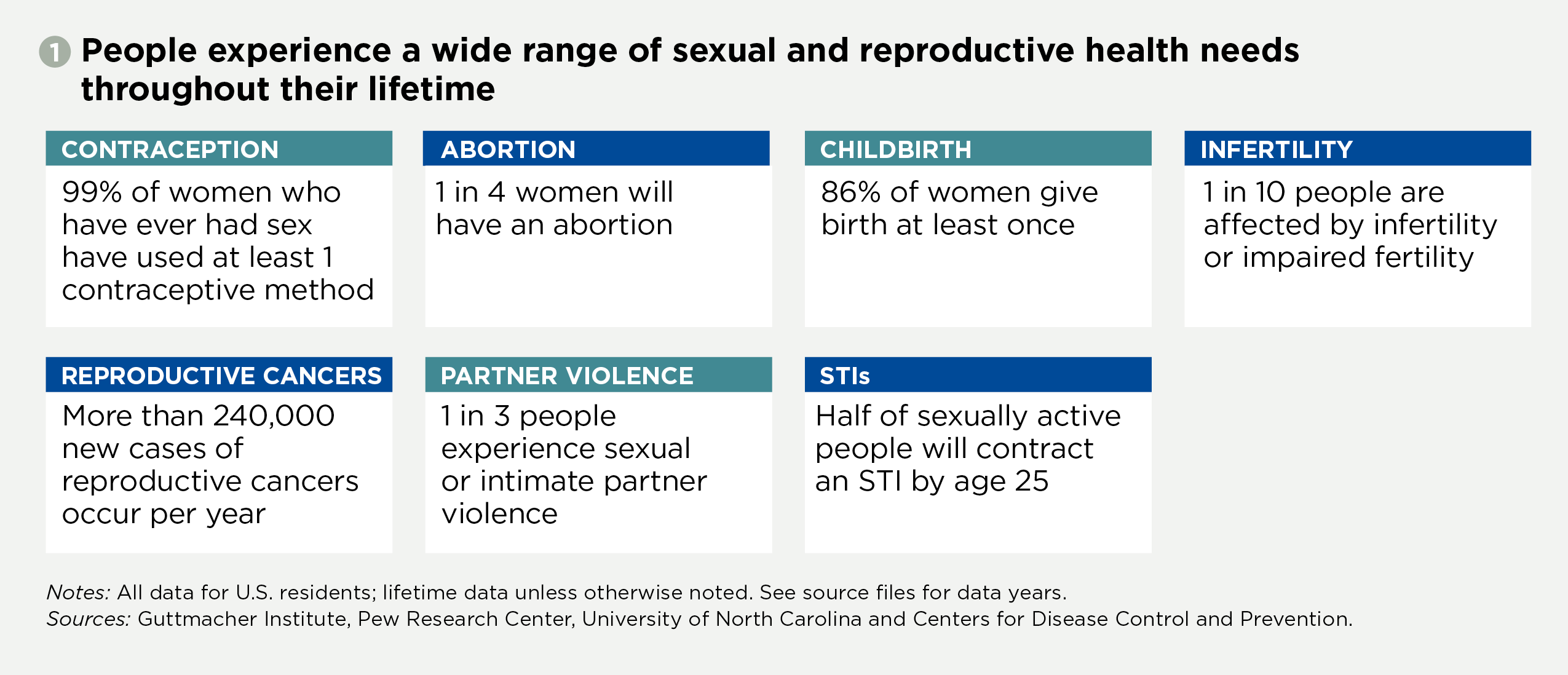

There are numerous sexual and reproductive health needs and interventions that affect people over the course of their lives, although some of those needs have historically been better served than others within the U.S. health care system (see figure 1).2–8 Ignoring any of these needs has serious consequences, in part because they cannot be addressed or understood in isolation: Patients experience their own health needs as part of an integrated whole, and the health care system should address them as such.

Contraception. Contraception is an essential and ubiquitous part of most people’s lives. Contraceptive care encompasses counseling that enables patients to have the information they need to make informed decisions; contraceptive drugs, devices and procedures; insertion and removal of devices; and follow-up care and continuing counseling to ensure that patients are satisfied with their methods and using them effectively.

Women in the United States typically spend roughly three years pregnant, postpartum or attempting to become pregnant and about three decades trying to avoid pregnancy (and therefore in need of contraceptive care).9 Consequently, nearly all women of reproductive age who have ever had sex have used at least one contraceptive method, and the vast majority will use several during their lifetime.2 Furthermore, people rely on a wide variety of methods used by both partners, often simultaneously.10 Among sexually active women seeking to avoid pregnancy, 90% are currently using at least one contraceptive method.11

Contraception has myriad benefits for all individuals, their families and communities. For example, only 5% of unintended pregnancies in the United States occur annually among women who correctly and consistently use contraceptives.9 Also, decades of research and women themselves say that family planning helps them to complete their education, get and keep a job, and take care of themselves and their families (see "What Women Already Know: Documenting the Social and Economic Benefits of Family Planning," Winter 2013).

Federal law, regulations and guidance provide strong protections in both public and private insurance designed to ensure that enrollees are able to choose contraceptive methods and services that best fit their needs, without financial or administrative barriers. Some states have amended and expanded their insurance requirements to match or go beyond these standards, including 29 states that require private insurers to cover prescription contraceptives12 and 25 states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility specifically for family planning services.13 However, some coverage gaps do remain, especially with regard to religious and moral objections,14 contraceptive method choice10 and insurer restrictions based on financial—rather than medical—reasons.

Abortion. The health care system should be prepared to meet the needs of people who choose to terminate a pregnancy for any reason. Medication abortions, which can be administered up to 10 weeks’ gestation, now account for almost one in three nonhospital abortions in the United States.3 Surgical abortion methods can also be performed throughout pregnancy. Both forms of abortion often include related services, such as counseling, ultrasounds and follow-up care.

With one in four women in the United States terminating a pregnancy at some point in her life, abortion is one of the most commonly used services in the health care system.3 The benefits of adequate abortion coverage and care are both immediate and enduring: For example, women who are able to obtain an abortion have a lower chance of experiencing poverty or unemployment than those who are denied care.15

The full range of abortion options should be available and covered by all health insurance plans, yet many patients face substantial coverage barriers. The Hyde Amendment bans the use of federal funds for abortion under Medicaid except in limited circumstances, effectively making abortion care a privilege for those who can afford it.16 Abortion coverage is not guaranteed in private insurance plans either, and half of states ban abortion coverage in at least some types of private health insurance.17 Furthermore, abortion restrictions are ubiquitous at the state level: Since 2011, states have enacted 424 new abortion restrictions, many of which conflict with scientific evidence.18

Maternal and newborn health. The health of new mothers and their infants is greatly shaped by the services available before and during a woman’s pregnancy and delivery, and the first months of a child’s life. Such services include not just labor and delivery care, but also comprehensive preconception, prenatal and postpartum care to manage existing or emerging health issues; counseling on nutrition, breastfeeding and newborn care issues; and the prevention and treatment of complications during and after pregnancy.19 Newborn health services overlap with maternal health services and include child-specific immunizations, disease screenings and treatment.20

Of course, everyone benefits from maternal and newborn health coverage. Eighty-six percent of U.S. women will give birth at least once in their lives,4 and approximately four million babies are born each year.21 Moreover, pregnancy and delivery can pose considerable risks, and the United States has high rates of maternal and newborn complications and deaths compared with other developed nations.22

Appropriately, maternity care is required under both public and private health insurance plans. Federal law requires states to cover maternity care—including prenatal care, labor and delivery, and 60 days of postpartum care—under Medicaid, as well as health care for infants born to any woman whose pregnancy is covered through Medicaid. The ACA requires private plans sold to individuals and small employers to cover 10 categories of essential health benefits, one of which is "maternity and newborn care." That provision closed several loopholes in the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, which has long required such coverage for most people with employer-sponsored health insurance.

Infertility. Infertility services support individuals’ ability to freely decide the number, spacing and timing of their children. The demand for infertility services has been increasing, both because of the trend toward later childbearing in the United States (a correlate of infertility) and innovations in infertility technology and services. Infertility services include fertility assessments and counseling, hormone treatments, surgery, sperm and egg donation, in vitro fertilization and other assisted reproductive technologies.

Infertility and impaired fertility affect roughly one in 10 men and women of reproductive age in the United States.5 Beyond the obvious consequences for people’s ability to have the families they desire, infertility can present a host of emotional and medical hurdles.23 Infertility care is also expensive: The median cost for a successful treatment ranges from approximately $1,000 to $40,000, depending on the services needed.24

These high costs are particularly problematic because many infertility services are inadequately covered or excluded entirely from public and private insurance programs.25 Just 16 states have any requirements for insurance companies around infertility services.26 The details of those requirements—and of the coverage provided by individual insurance plans—vary widely, in terms of the specific services included and any limits placed on that coverage.

Reproductive cancers. Reproductive cancers present a serious threat to sexual function, fertility and overall health. Services to avert, identify and treat such cancers include counseling, screening and testing (such as Pap and human papillomavirus [HPV] tests), preventive measures (such as HPV vaccinations) and treatment services (including radiation, chemotherapy and surgery).

The most common and life-threatening types of reproductive cancer are cervical, ovarian, uterine and prostate, which were responsible for 57,000 deaths in the United States in 2015.8 For all cancers, prevention efforts, early detection and adequate treatment boost survival rates and quality of life. For instance, since the Pap test was introduced in the 1950s, cervical cancer deaths have decreased 74%.27

The ACA’s preventive services provision requires private insurance plans to cover cervical cancer prevention and screening procedures, and to do so without patient cost sharing. This provision also applies to some Medicaid enrollees, and state Medicaid programs almost universally cover many of these services even where there is no federal mandate.28 Other reproductive cancers are subject to the same coverage rules as other types of cancer; testing and treatment for cancer is typically included under private and public insurance plans as part of broader benefits for physician services, hospital care and prescription drugs.

Sexual or intimate partner violence. Intimate partner violence encompasses acts of stalking, psychological aggression, and physical or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner.29 Approximately one in three people in the United States experience sexual violence, physical violence or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.6 These violations can also be committed by people who are not intimate partners, though often the victim and perpetrator know one another.30 Sexual and intimate partner violence has implications well beyond sexual or reproductive health; long after the violence has stopped, survivors may experience chronic stress, depression and complications from physical injuries, among other types of mental and physical harm.31

Sexual and intimate partner violence requires interventions beyond the health care system in a way that other sexual and reproductive health issues do not (see "Understanding Intimate Partner Violence as a Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Issue in the United States," July 2016). However, the health sector can take immediate and crucial steps to respond to people who have experienced violence by providing referrals to trusted advocacy service providers and adopting trauma-informed models of health care. Providers can also offer emergency contraception to survivors of sexual assault, and help people identify and adopt methods of contraception that will work for them if they fear coercion around contraception or pregnancy.

Currently, the bulk of federal policy efforts intended to address these types of violence are directed to legal and criminal justice interventions. However, the ACA does include some relevant provisions. For example, the law’s preventive services section requires coverage without cost sharing for "interpersonal and domestic violence" screening and counseling services. The ACA also requires marketplace plans to offer a special enrollment period for people experiencing domestic abuse and their dependents so that they do not have to wait for the standard year-end enrollment period.32

HIV/AIDS and other STIs. Approximately 40,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with HIV each year.33 More than 1.1 million people are living with the disease, and a substantial minority of them are unaware of their status. Although HIV is still not curable, prevention and treatment methods have improved over the last three decades. In fact, young people diagnosed with HIV now who receive adequate care have a life expectancy on par with the general population.34

Besides HIV, there are more than two dozen infections transmitted largely or exclusively through sexual contact. Some are curable (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis), while others are incurable but manageable with adequate health care (e.g., hepatitis B, herpes simplex virus and HPV).1 When left untreated, STIs can result in cervical cancer, infertility, poor pregnancy and birth outcomes, and increased risk of acquiring new or transmitting existing STIs.35 New cases of several of the most closely tracked STIs—chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis—increased each year from 2013–2017.36

Health insurance plans can address HIV and other STIs by covering screenings, treatment and follow-up care, but this coverage is inconsistent. Private plans are required to cover HIV and STI counseling and screening, as well as vaccinations for HPV and hepatitis B, without patient cost sharing.37 A pending recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force would add pre-exposure prophylaxis (a pill that can prevent the acquisition and spread of HIV) to this list.38 The same coverage requirements pertain for some, but not all, Medicaid enrollees, so coverage can vary under Medicaid for specific STI services.37

Additional sexual and reproductive health needs. Throughout the course of their lives, people experience a wide range of other sexual and reproductive health needs. Nearly everyone who menstruates experiences related pain or discomfort at some point in their life and a substantial minority are affected by heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome.39–41 Additionally, many women experience symptoms during menopause that require medical intervention, including infections, depression, anxiety, incontinence, problems sleeping and hot flashes.42 In all of these cases, medical guidance and intervention may be necessary to identify underlying causes and mitigate symptoms.

Pleasurable sexuality is often overlooked in health coverage and care, but it is a natural and healthy part of life that the medical community has a responsibility to support: All people have a right to positive sexual experiences, not simply the absence of disease. Providers should talk to patients about the components of healthy and satisfying sex and address the underlying causes of its converse, sexual dysfunction.43

Addressing Systemic Inequities

Many people experience health needs or disparities specifically related to their income, race, ethnicity, immigration status, age, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability status, among other characteristics. Inequities in health outcomes are varied and may stem from stigma and discrimination surrounding these characteristics, not the characteristics themselves. Efforts to address these inequities should go well beyond the health sector, including policies that promote financial assistance for families, safe and affordable housing, fair criminal justice reform, adequate educational opportunities and compassionate immigration reform.

Individuals can (and often do) experience multiple and intersecting forms of social exclusion. In addition, stressors resulting from chronic discrimination of various forms may have deleterious effects on individuals’ health. It is critical that providers and the health system in which they operate be cognizant of and responsive to the distinct needs of the people they serve.

For low-income people, the financial burden of health care can be exorbitant. Many people who obtain an abortion, for example, are forced to forgo or delay basic expenses such as rent and food to pay for the direct and indirect costs of the procedure (e.g., lost wages, transportation and childcare).44 For women who give birth, the average out-of-pocket cost for maternity care is approximately $16,500, more than half of the average income for a woman of reproductive age.45

Racial and ethnic health disparities are closely linked to economic ones, but people of color face the additional barrier of structural racism and its consequences.46 This is starkly reflected in maternal health outcomes: Black women’s rates of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity are much higher than those of white women, and persist even when controlling for education and income.47,48 Immigration status (which is closely associated with race and ethnicity) is tied to additional barriers, such as policies blocking immigrants from educational opportunities, jobs with benefits, affordable housing, and adequate health coverage and care.49 These barriers are evident in disparities in insurance status: 32% of noncitizen women aged 15–44 were uninsured in 2017, compared with only 9% of U.S.-born women.50

The health care that young people—and particularly minors—receive may be limited by confidentiality concerns, lack of insurance or independent financial resources, inadequate sexual education or stigma. Furthermore, people of all ages who identify as LGBTQ or intersex face discrimination, violence and social exclusion that can undermine their health. Bisexual women, for example, experience nearly double the lifetime rates of intimate partner violence as their heterosexual peers,51 and medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex newborns can result in lifelong health issues.52

Transgender people face significant barriers to care when insurance plans or providers are unprepared, unwilling or ill equipped to meet their needs.53 In addition to the sexual and reproductive health needs discussed above, transgender people may seek gender-affirming care that includes hormone therapy, surgery and mental health care.

In addition, the current health care system makes minimal accommodations for the estimated 61 million people in the United States with mental or physical disabilities.54 Women with physical disabilities, for example, are less likely to receive Pap tests than women without disabilities because the medical equipment may not be designed for their bodies.55 Furthermore, people with physical or mental disabilities may not be screened for STIs or receive preconception care because of provider assumptions that they are not sexually active.

Fully addressing sexual and reproductive health needs and systematic inequalities in this area is an ambitious goal that requires an equally ambitious approach. Requiring insurance plans to cover a few select reproductive health services—as many health care reform proponents recommend—would be wholly inadequate. Rather, policymakers and stakeholders need a comprehensive vision that lays out what comprehensive coverage, a strong network of providers and robust patient protections should look like in order to fully address the sexual and reproductive health needs that shape people’s lives.

Editor’s note: This article is the first installment in a two-part series on how sexual and reproductive health and rights fit into health care reform efforts. The other article lays out a vision for addressing sexual and reproductive health needs within the health care system.