Socially conservative policymakers and activists routinely assert that making sexual and reproductive health information and services more available promotes promiscuity. Their argument often focuses on the timing of sexual initiation, but can also include behaviors such as increased sexual frequency or sex with more partners. There are two related assumptions underpinning this claim: One, the availability of information or services related to sexual and reproductive health signals to young people (and especially young women) that society approves of them having sex and will prompt them to initiate sex. The second, closely related assumption is that being able to obtain such knowledge or services will allow people to reduce the perceived negative consequences of sex and incentivize them to have intercourse for the first time, more frequently or with more partners.

Although the evidence does not support these assumptions and claims, social conservatives nevertheless have long employed them to block or undermine policies and programs they oppose on ideological grounds. For instance, the Family Research Council has warned that young women who receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine "may see it as a license to engage in premarital sex."1 The evangelical leader Franklin Graham has called comprehensive sex education an "agenda to lure [children] into promiscuity."2 And in justifying its regulations to undermine the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) birth control benefit, the Trump administration has argued that the policy could "among some populations, affect risky sexual behavior in a negative way."3

In addition to serving as a political cudgel, the promiscuity argument advances social conservatives’ cause in other ways. The argument attempts to stigmatize sex outside of heterosexual marriage, seeks to shame sexually active young people and young women in particular, and intentionally ignores the fact that for most people, sex is a normal part of adolescence and adulthood. The goal is not just to make information and services less available, but to undercut people’s personal autonomy and compel them to act in accordance with a socially conservative worldview (see "Coercion Is at the Heart of Social Conservatives’ Reproductive Health Agenda," 2018).

The Scientific Evidence

In evaluating how the promiscuity argument applies to various programs or policies, it is important to review the body of evidence as a whole. Common strategies to mislead policymakers and the general public include cherry-picking scientific studies while ignoring the bulk of the evidence, taking a study’s findings out of context and drawing conclusions from a study that are not supported by the study’s actual findings.

Publications that review or synthesize findings from multiple individual studies—such as systematic reviews or meta-analyses—can be especially valuable in comprehensively assessing the evidence. These analyses are designed to draw broader conclusions about an evidence base and can help readers steer clear of outliers—that is, individual studies at odds with the larger body of evidence.

HPV Vaccination

HPV is the most common STI in the United States, affecting approximately 80 million people.4 While most cases of HPV infection clear on their own, more than 43,000 people in the United States were diagnosed in 2015 with a cancer caused by an HPV infection.5 Most of these cancers could be prevented through available vaccines,6 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys aged 11–12.7 However, while vaccination rates have increased steadily since the HPV vaccine was introduced, uptake has lagged significantly behind that of other childhood vaccinations. Nearly 66% of U.S. adolescents aged 13–17 had received one or more doses of HPV vaccine in 2017,8 compared with almost 90% coverage for the tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis vaccine.7 One likely reason for this slow uptake is that social conservatives have strenuously opposed making HPV vaccination mandatory for school attendance, as is common for other childhood vaccinations;9,10 as of 2019, only Rhode Island, Virginia and the District of Columbia require HPV vaccination.11

The premise for social conservatives’ opposition to HPV vaccine requirements—that it would lead to more sexual activity—is soundly contradicted by the evidence, with several systematic reviews and numerous individual studies coming to similar conclusions. A 2016 systematic review synthesized 20 studies published between 2008 and 2015 from a diverse group of countries.12 Seventeen of the studies looked at one or more self-reported sexual behaviors among postvaccination males and females, including sexual activity, age at sexual debut, number of sexual partners and contraceptive use. Nine of the studies examined biological outcomes among the same groups, including HIV/STI testing. The authors conclude that the body of studies they reviewed shows that HPV vaccination does not lead young people to initiate sex or have it more frequently because they believe they are at lower risk of HPV infection, and none of the studies showed evidence of higher rates of STIs. Moreover, the authors state that "there appeared to be more support for the fact that vaccinated women actually showed less involvement in risky behaviors than unvaccinated women, which was evidenced by lower numbers of sexual partners and increased use of contraception."12

Another 2016 systematic review of 21 studies,13 looking only at girls and adult women, likewise found no evidence that HPV vaccination is associated with changes in sexual behaviors due to vaccinated women feeling they were at lower risk of negative consequences. The authors of this review, too, conclude that "data from the 21 included studies showed either no association between vaccination status and the outcomes of interest, or indicated a positive association between safer sexual behaviors and receipt of HPV vaccination."13

Further, a large-scale 2018 study of almost 300,000 young women in the Canadian province of British Columbia found that a school-based HPV vaccination program resulted in adolescent girls reporting either a decline or no change in sexual activity, leading the authors to conclude that "these findings contribute evidence against any association between HPV vaccination and risky sexual behaviours."14

Contraceptive Use and Access

Since contraceptives are widely used and policies making them more accessible are politically popular, the promiscuity argument has long been a favorite pretext under which U.S. conservatives attack contraceptive access. This strategy included making ugly insinuations against women who use contraceptives during the 2012 debate over regulations guiding the ACA’s birth control benefit.15 It has also included much public handwringing during the lengthy process of making emergency contraception available over the counter; conservatives argued that doing so would lead to young women taking more sexual risks.16 When deployed to undermine contraceptive access, the promiscuity argument often goes hand-in-hand with conservatives’ insistence that contraception is not effective and that contraceptive use will inevitably lead to more pregnancies and abortions because it will cause more sexual activity.17

However, the scientific literature strongly rebuts this narrative. For instance, a 2007 paper by Santelli and colleagues found that the vast majority (86%) of the decline in adolescent pregnancy between 1995 and 2002 resulted from improvements in contraceptive use, including an increase in adolescents using contraceptives.18 This trend occurred even as sexual activity fell, accounting for the remaining 14% of the decline in pregnancy. Further, the decline in adolescent pregnancy risk during the 2007–2014 period was entirely attributable to better contraceptive use, according to a 2018 study by Lindberg and colleagues.19 During this time period, more adolescents were using contraceptives, they were using more effective methods and they were using them more consistently—all while adolescent sexual activity rates remained stable.

Evidence focused on one specific method—emergency contraception—further bolsters this conclusion. A 2011 paper by Meyer and colleagues reviewed seven randomized controlled trials of advance provision of emergency contraception to women aged 24 years and younger.20 Six of those seven studies found no decreases in contraceptive use or increases in risky sexual behaviors. Only one study found any negative impact, albeit for a small population subgroup, showing that parenting young women who receive advance provision of emergency contraception may be more likely to have unprotected sex.21 But that same study also affirmed the overall body of evidence, showing that advance provision of emergency contraception "increases the likelihood of its use, and does not affect the use of condoms, or hormonal methods of birth control."21

The Trump administration has justified its attacks on the ACA’s contraceptive coverage benefit in part by suggesting that increased access to contraception results in increased sexual behavior and increased adolescent pregnancy rates in the long term.3 In making this argument, the administration relies on a single paper finding that "programs that increase access to contraception are found to decrease teen pregnancies in the short run but increase teen pregnancies in the long run."22 This paper is based on hypothetical models, with a set of assumptions feeding into a simulation, rather than evidence from actual programs and resulting contraceptive use. Further, this hypothetical conclusion is at odds with both the overall body of evidence and a two-and-a-half-decade trend of rising adolescent contraceptive use, stable or decreased sexual activity and sharply falling pregnancy rates.18,19,23 Given these realities, the paper begs the question of when the "long run" will manifest itself.

Sex Education Programs

One of social conservatives’ main lines of attack against sex education and other efforts to reduce adolescent pregnancy has long been to allege that they encourage promiscuity—unless they focus exclusively on promoting abstinence outside of marriage. This argument has surfaced in various contexts at the local, state and federal levels, including in debates about whether federal funding should support comprehensive approaches to sexuality education (as promoted by the Obama administration) or be funneled to abstinence-only-until-marriage programs (as promoted by the Trump administration).24,25

However, the scientific literature going back decades demonstrates overwhelmingly that social conservatives’ promiscuity argument on sex education is false. Several large-scale systematic reviews of dozens of studies from the 1970s to the 1990s consistently found no indication that sex education contributed to earlier or increased sexual activity in young people.26–28 Most of the reviewed studies found either no change in behavior, or that young people adopted safer sex practices; only a small minority of studies found an association between sex education and increases in sexual activity. In the words of one author, "the overwhelming majority of reports reviewed here, regardless of variations in methodology, countries under investigation, and year of publication, found little support for the contention that sexual health education encourages experimentation or increased sexual activity."28

Several other studies have upheld that same conclusion. A 2007 review by Kirby summarizes findings from 56 studies of curriculum-based sex education programs in the United States published between 1990 and 2007.29 Of the 40 studies in this review measuring sexual initiation, 16 found a significant delay and none found earlier initiation, while of the 27 studies looking at sexual frequency, eight found a decrease and none reported an increase. Importantly, findings on other indicators drive home the imperative to focus on the overall body of evidence rather than individual outliers: Among 29 studies measuring number of sexual partners, 12 showed a decrease in the reported number of sexual partners and only one found a significant increase. Of 13 studies measuring the impact of programs on contraceptive use, only one reported decreased use of contraceptives. Likewise, of 12 studies measuring the impact on pregnancy rates, only one found a significant increase. And of 10 studies looking at the effect of sex education programs on STIs, only one found a significant increase in STI rates (possibly a function of more young people getting tested rather than an actual increase). The author concludes that "comprehensive programs, in contrast [to abstinence-only programs], show strong evidence of positive effects on behavior and no consistent negative effects." Another 2007 review by Kirby and colleagues came to very similar conclusions.30

A pair of 2012 systematic reviews by Chin and colleagues examining 62 studies published between 1988 and 2007 likewise found that comprehensive risk-reduction interventions were associated with declines in various risk behaviors among adolescents.31 Only one of the 62 studies suggested a potential negative impact. The evidence base is further bolstered by a United Nations–commissioned 2016 review of 22 systematic reviews, which found that curriculum-based comprehensive sex education programs contribute to delayed initiation of sexual intercourse, decreased frequency of sexual intercourse, fewer sexual partners and less risk taking.32

Most recently, a 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies published between 1984 and 2016 assessed the effectiveness of school-based programs related to youth pregnancy prevention.33 The review found that these programs did not increase sexual initiation, but rather led to a significant reduction in the likelihood of initiating sex in the 13-month period following the programs, and were not associated with sex at later follow-ups. In other words, they neither increased nor decreased sexual risk.

School-based Health Centers and Condom Programs

For decades, a contentious debate has raged around whether contraception should be available to adolescents in schools, either through comprehensive health services in school-based health centers (SBHCs) or stand-alone condom promotion programs. Attacks centered on variations of the promiscuity argument have had a significant, lasting impact on the type of health services SBHCs provide.34 A 1994 report by the General Accounting Office concluded that controversies over family planning services constrained the ability of SBHCs to meet some adolescents’ health needs,35 and more recent analyses show that such manufactured controversies have played major roles in continuing to block many SBHCs from providing contraceptive services.34 Also, many religiously affiliated schools across the country ban condoms,36 as do some public schools.37,38

However, the evidence clearly shows that making contraceptives available in school-based settings does not cause more sexual activity. Rather, several studies of SBHCs that provide contraceptives have shown that contraceptives’ availability, as intended, increases students’ use of contraception.39,40 Meanwhile, the evidence going back decades has not found any associated increases in sexual activity. As far back as 1991, a study by Kirby and colleagues of three school-based clinics offering condoms or other forms of contraception along with comprehensive health services showed that the presence of the clinic was not associated with increased sexual activity.41 A 2007 review by Kirby likewise concluded that "providing contraceptives in school-based clinics does not hasten the onset of sexual intercourse or increase its frequency," although it also noted that the number of studies was small and of mixed quality.29

More recently, a 2010 review based on 30 studies—while focused mostly on the United Kingdom—reported that there was evidence from higher-quality U.S. studies that school-based health services do not increase rates of sexual activity or lower the age of first sexual intercourse.42 Further, a 2016 paper synthesized 37 systematic reviews covering a range of school-based interventions to improve sexual health.43 This review of reviews underscores the importance of looking at the preponderance of the evidence, rather than individual outliers. For instance, while one of the systematic reviews44 found some evidence suggesting an increase in sexual activity associated with school-based provision of contraception, those impacts showed up in only one of the review’s 29 studies.

Studies looking at the provision of condoms in school-based settings draw similar conclusions. Two 2018 reviews,45,46 of nine and 12 studies, respectively, found that school-based condom availability programs were not associated with increases in sexual and other risk behaviors. The authors of one review conclude that "school-based [condom programs] may be an effective strategy for improving condom coverage and promoting positive sexual behaviors."45 In addition, a 2019 review of 29 studies on condom availability programs from six countries reported that such programs did not lead to more sexual activity or more sexual partners and did not lower the age at which people first have sex, while leading to more condom use and lower STI rates.47

Meanwhile, a 2018 study on condom promotion programs illustrates powerfully that even when the topline findings show a negative impact, they may not support the conclusions drawn by social conservatives. This study collected information on condom distribution programs implemented in the 1980s and 1990s in 484 schools across 11 states and the District of Columbia, with findings suggesting that the introduction of such programs in schools is associated with an increase in teenage fertility.48 However, the authors say, "we find that the fertility increase is driven by communities where condom access was provided without mandated counseling, and that these fertility effects may have been attenuated, or perhaps even reversed, when counseling was mandated as part of condom provision."48 In other words, the context and quality of condom programs matter a great deal, and providing students with more information impacts outcomes. The authors add that this critically important nuance could also explain why their study’s findings were are at odds with those of a 2016 study49 that school-based health clinics offering contraceptive services significantly decreased teen fertility.

False Arguments, Real Harm

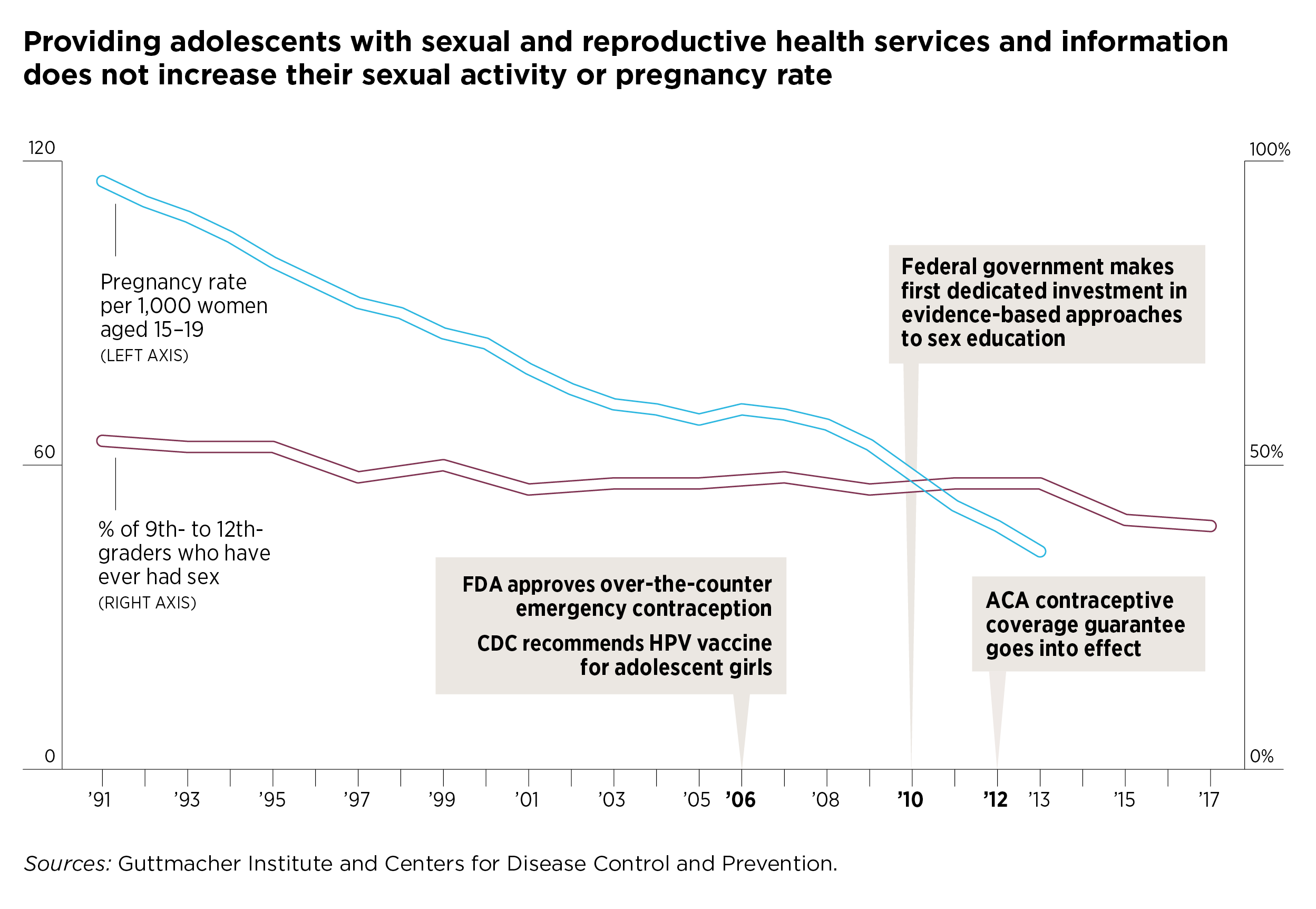

In addition to the scientific literature discussed above, population-level evidence serves as an important check on the basic plausibility of social conservatives’ claims, and the promiscuity argument fails this common-sense test decisively. Over time, rates of HPV vaccination have increased steadily,7 contraceptive use has improved among adolescents,19,50 the federal government has made its first dedicated investments in approaches to sex education beyond abstinence-only curricula,51 and contraceptives have become more available to millions of people thanks to the ACA’s birth control benefit52 and Medicaid expansion.53

Taking social conservatives’ claims at face value, these developments all should have led to more adolescents initiating sex, as well as people generally having more sex and with more partners. That, in turn, should have resulted in more pregnancies, births and abortions. In reality, none of this has come to pass (see figure). For decades, adolescent sexual activity has either remained stable or decreased; only 40% of U.S. high school students reported in 2017 that they had ever had sex—the lowest level since these data were first collected in 1991.54 Meanwhile, rates of adolescent pregnancies, births and abortions have all been plummeting for decades, mostly as the direct result of improved contraceptive use.23 Likewise, for the population overall, there is no evidence that sexual activity has increased—and pregnancy, birth and abortion rates have been declining.55,56

While the scientific literature and population-level trends soundly debunk the argument that access to information and services leads to increased sexual activity, some social conservatives have seized on the trend of rising STI rates in the United States as validation for their claims and justification for pushing their policy preferences, including abstinence-only programs.24 However, with levels of sexual activity declining among young people, and stable for the rest of the U.S. population, changes in levels of sexual activity do not appear to be the driving factor behind rising STI rates.

Rather, public health experts attribute the increase in STI rates to a range of other factors. Some experts cite a significant drop in prevention funding,57 which has contributed to an erosion of public health infrastructure at the local and state levels for STI prevention and treatment.58,59 Additionally, declines in condom use and a general lack of knowledge about STI risks and how to prevent transmission are seen as contributing factors—making it deeply ironic that social conservatives are attempting to use the increase in STIs as a pretext to attack sex education and efforts to make condoms more available.

And herein lies the root of the problem. By turning public health debates into ideological battles premised on falsehoods, social conservatives have done immense damage to the nation’s ability to develop and maintain effective public health interventions and to fund them at appropriate levels. The people whose rights and health are most directly compromised by these attacks are those who are most reliant on public health interventions for their health information, coverage and care. This includes young people, those with low incomes and people of color—all groups that often have few resources or are otherwise marginalized. The damage is compounded by the promiscuity argument’s inherent shame and stigma, usually targeted at the behaviors of young women, which can further constrain people’s ability to obtain needed information and services.

The negative impact of these tactics has become particularly acute under the Trump administration: Social conservatives in Congress and various government agencies are waging a relentless campaign to undermine critical public health policies and programs, including the ACA, Medicaid, Title X and the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program. And while these attacks are grounded in ideology, social conservatives routinely attempt to deceive policymakers, the media and the public into thinking that their agenda is based on evidence—with the false promiscuity argument a prime example.

The author wishes to thank Sheila Desai and Laura D. Lindberg for their assistance throughout the preparation of this article.