Several other historically marginalized groups will be impacted by these Medicaid cuts in smaller or less direct ways. For example, the law newly bars refugees and asylum seekers from Medicaid coverage, adding to the high numbers of non-citizens already excluded from the program. At the same time, the CBO estimates that the law will prevent higher numbers of non-citizens from enrolling in ACA marketplace plans, where many more immigrants who are lawfully present have lost eligibility for the subsidies that make coverage affordable. While pregnant and postpartum women and adolescents 18 and younger are not part of the ACA Medicaid expansion population and are exempt from most of the restrictions and direct cuts, they—like many others—could be indirectly affected by other cuts in the federal budget law, as states are forced to roll back coverage. For example, the law reduces retroactive eligibility (under which a new Medicaid enrollee can seek coverage for medical expenses incurred prior to their enrollment), a feature of the program commonly used to make Medicaid coverage more accessible to pregnant people.

Impact of Coverage Losses

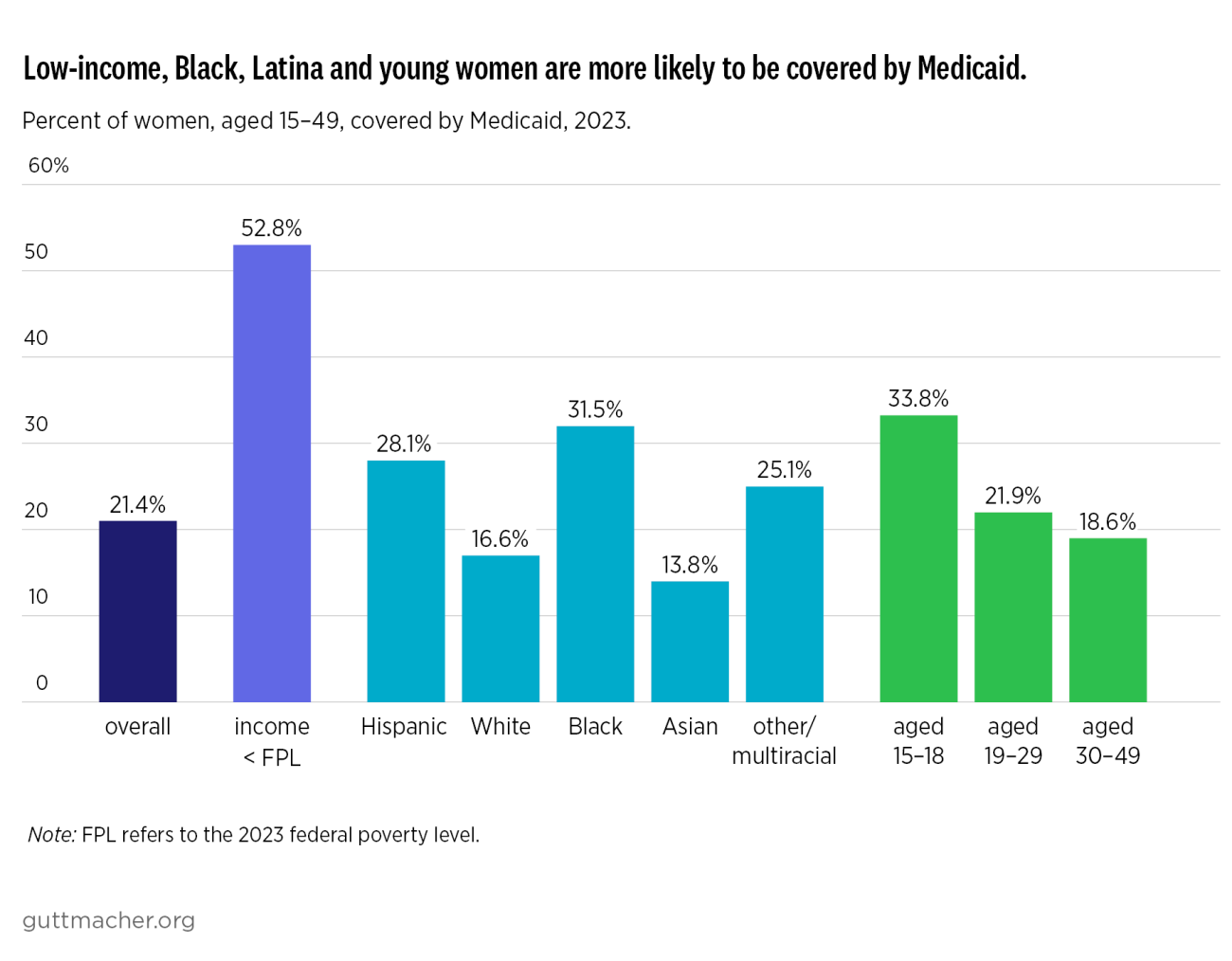

Loss of Medicaid coverage has potentially severe consequences for the sexual and reproductive health, rights and autonomy of individuals. Cost is a known barrier to care for people without insurance. For example, 20% of uninsured women reported having to stop using contraception in the previous year because they couldn’t afford it, a far higher rate than that reported by women with Medicaid or private insurance. Similarly, out-of-pocket costs can also lead to discontinuation or gaps in use and can restrict individuals’ choice of contraceptive methods. These infringements on method choice and use are violations of reproductive autonomy and may also lead to incorrect and ineffective contraceptive use, which in turn can lead to unwanted pregnancy. Loss of coverage can also result in a range of health, social, economic and logistical problems, including pregnancy-related health risks, aggravation of underlying health conditions, difficulties finding accessible and affordable health care providers, and additional strains on patients’ time, budget and relationships.

Fewer people being insured through Medicaid could also lead to increased burdens on health care providers, particularly publicly supported family planning clinics. According to unpublished NSFG tabulations, 42% of patients at publicly supported clinics paid with Medicaid, compared with only 18% of patients at other providers. As a result of Medicaid cuts, many of these patients will now be uninsured and in need of free or discounted care. Even in an otherwise ideal economic and political climate, replacing that level of lost reimbursement would be a daunting challenge. But publicly supported clinics are already facing numerous financial strains and political attacks, including: the federal budget law’s ban on Medicaid reimbursements for Planned Parenthood affiliates and other providers; the Trump administration’s withholding of Title X family planning funding; new regulations reinterpreting federal law to deny services to many immigrants through Title X, federally qualified health centers, and other programs; and a chaotic post-Dobbs abortion landscape that has forced clinics to meet increased demand for contraception and abortion in some places and to navigate complex legal barriers in others.

Furthermore, state budgets will also be seriously impacted by the federal budget law, as it shifts costs from the federal government to the states and restricts states’ ability to raise Medicaid revenue through taxes on health care providers. States will incur substantial new administrative costs to set up and enforce work requirements, reassess enrollees’ eligibility more frequently, and implement a host of other new bureaucratic rules. States will also end up subsidizing emergency room care and other services for people who end up uninsured, as well as responding to other financial strains caused by cuts to health, education and social programs imposed by the Trump administration and Congress.

Too many states may be tempted to respond to these shortfalls by restricting Medicaid eligibility or eliminating optional benefits and programs. These measures could harm SRH care through such steps as restricting Medicaid enrollees’ choice of contraceptive methods, limiting or eliminating Medicaid family planning expansions, or making cuts to non-Medicaid funds for family planning, HIV/STI, pregnancy and other programs.

Mitigating Harm While Fighting for Repeal

The negative impacts of these federal Medicaid cuts on sexual and reproductive health, rights, and autonomy are clear, and Congress should repeal these and other components of the budget law. While some provisions of the law are already having an impact, states have until January 2027 before they must begin enforcing the work requirements and more frequent eligibility redeterminations, among other provisions. This provides an opportunity for policymakers and health advocates to push for their repeal, and in fact, a demand by Democratic members of Congress to repeal the Medicaid cuts has been central to the current government shutdown.

In the meantime, state policymakers will need to make plans to mitigate the harm of these measures. Importantly, states should help as many people as possible stay insured through Medicaid by taking advantage of opportunities under the new law that make it easier for individuals to learn about Medicaid eligibility rules, sign up for the program and stay enrolled. For example, in implementing work requirements, states will be able to choose how they verify compliance, how effectively they use existing data to automate verification, what optional exemptions they adopt, and how they communicate with enrollees. State policymakers should take lessons from the botched and harmful rollout of Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas and Georgia, where thousands of people were dropped from or denied coverage even if they qualified.

Health care providers such as federally qualified health centers and publicly supported family planning clinics should also do what they can to help enrollees get and stay enrolled in Medicaid, and states should support and invest in such point-of-care efforts. These providers have a strong incentive to offer enrollment assistance, and many have experience doing so for states’ Medicaid family planning expansions and for the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces.

Similarly, states should implement presumptive eligibility for pregnant people, allowing Medicaid-eligible patients to receive services the same day they start the Medicaid enrollment process. More than half the states have already taken this critical step, which avoids delays in care and immediately exempts enrollees from work requirements.

States Must Recommit to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services

In the face of these funding challenges, states have a critical role to play in shoring up access to sexual and reproductive health care. State policymakers should prioritize those efforts, rather than scaling back their advocacy and investments. Cuts to reproductive health services would negate the savings garnered from preventive care, undermine reproductive autonomy, and lead to more unwanted pregnancies, STIs and cervical cancer cases.

Policymakers should consider all options for supporting SRH services. To start, states should initiate or build on existing Medicaid family planning expansions, which have been demonstrated by numerous program evaluations to provide net savings for Medicaid. Specifically, State Plan Amendments for family planning should be used to give people who lose full-benefit Medicaid coverage an opportunity to still receive contraceptive services and supplies, screening and treatment for STIs, lab tests and more. In addition, states should also consider new funding for SRH and other services at publicly supported clinics, to help them keep their doors open and serve both those patients who manage to stay enrolled in Medicaid and the many other patients who will be left uninsured. Finally, another approach would be for states to maximize the flexibility of telehealth services covered by Medicaid to expand access to sexual and reproductive health care, and ensure that as many SRH services as possible are covered.

The federal budget reconciliation law is a serious threat to Medicaid coverage for millions of women of reproductive age, with the potential to undermine their access to essential care as well as their sexual and reproductive health, rights, and autonomy. Federal and state policymakers can and should act quickly to mitigate the harmful effects of this law and to bolster sexual and reproductive health services across the United States.

Methodology

The estimates of the number of women of reproductive age who might lose Medicaid coverage because of work requirements is based on data from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS 2023 1-year data). Guttmacher researchers first estimated the overall number of people on the ACA Medicaid expansions in the ACS data (16.7 million) by limiting the group to people in states that had implemented an expansion and who were aged 19–64 with a family income below the state’s eligibility threshold for the expansion (generally 138% of the federal poverty level). Researchers also excluded people who were on Medicare and/or Supplemental Security Income, who had had a child in the past 12 months, or who were parents of dependent children with a family income at or below state-specific income eligibility thresholds—since all of those groups should be eligible for Medicaid outside of the ACA expansion. Among that overall number of people enrolled under the ACA Medicaid expansions, researchers restricted by age and gender to estimate that 6.7 million (40.14%) were women aged 19–49. They then applied that percentage to the total numbers of people who may lose Medicaid coverage by 2034 because of work requirements, according to projections from the CBO and from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.