- In 2016, 20.6 million U.S. women were likely in need of public support for contraceptive services and supplies.

- Between 2010 and 2016, the number of women likely in need of public support for contraceptive services and supplies rose 8% overall. Among women below 250% of federal poverty guidelines, there was a 12% increase; among adolescents, there was a 5% decline.

- Between 2013 and 2016, the number of women likely in need of public support for contraceptive services who had neither public nor private health insurance fell more than one-third (36%), from 5.6 million to 3.6 million. States that implemented the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion experienced particularly large declines.

- Between 2010 and 2016, the overall number of women receiving publicly supported contraceptive services remained stable at about nine million women. However, the number of women served by different types of providers shifted dramatically over this period.

- While Title X–funded sites continued to serve the largest segment of women receiving publicly supported care, their patient load fell by 25%, from 4.7 million in 2010 to 3.5 million in 2016. The number of contraceptive patients served by other public clinics that do not receive Title X funding rose by 29% and the number of women receiving Medicaid-funded contraceptive services from private providers rose by 19%.

- In 2016, women who obtained contraceptive services from all publicly supported providers were able to postpone or avoid two million pregnancies that they would have been unable to prevent without access to publicly supported care. Women who obtained contraceptives from Title X–funded clinics avoided 755,000 pregnancies.

- Screening and vaccination services provided at family planning visits with all publicly supported providers helped patients avoid more than 12,000 cases of pelvic inflammatory disease and nearly 2,000 cases of cervical cancer in 2016. More than 100,000 chlamydia infections, 18,000 gonorrhea infections and 800 cases of HIV were prevented among the partners of women obtaining publicly funded contraceptive care.

Publicly Supported Family Planning Services in the United States: Likely Need, Availability and Impact, 2016

Author(s)

Jennifer J. Frost, Mia R. Zolna, Lori F. Frohwirth, Ayana Douglas-Hall, Nakeisha Blades, Jennifer Mueller, Zoe H. Pleasure and Shivani KochharReproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

Key Points

Corrected November 13, 2019. See note.

Background

The vast majority of women* in the United States rely on contraception to prevent pregnancy at some point in their lives, and many need ongoing or periodic access to sexual and reproductive health care providers in order to obtain contraceptive counseling and supplies. The ability to have information on and choose from a wide range of contraceptive methods helps to ensure that women and their partners can obtain the methods that work best for their personal situation and current stage in life. Many women, however, cannot afford to pay for contraceptives and related services; others may be concerned with confidentiality when seeking care. These women are among many who turn to publicly supported providers to obtain the care they need and want.

A nationwide network of publicly supported clinics has long been the critical source of contraceptive care for adolescents and low-income adults. This network includes sites that are funded through the national Title X family planning program—the only federal grant program dedicated to providing subsidized contraceptive and related sexual and reproductive health services, with a focus on serving individuals who are disadvantaged in their access to health care—as well as sites that receive other types of public funding. Each year, this network serves millions of women and helps them prevent more than a million pregnancies and hundreds of thousands of births and abortions.1 In addition to this network of safety-net clinics, many women enrolled in Medicaid receive publicly supported contraceptive care from clinicians at private providers’ offices.

Estimating how many women are potential patients for this care and how many women publicly supported providers collectively serve is crucial for the planning and design of health care delivery systems and for measuring the impact of those services. Moreover, in a time of unprecedented change in health care financing and increased access to health insurance coverage, as well as significant threats to this access, it is even more important to continue monitoring the role and impact of publicly funded providers and programs.

Since the 1970s, the Guttmacher Institute has periodically estimated potential demand for contraceptive services and supplies in the United States, focusing on the number of women who likely need public support to obtain this care because of their income or age.2–7 Specifically, these estimates represent the number of women who, at some point during the year, may have a potential demand for contraceptive services or supplies because they desire to avoid or delay becoming pregnant. In the past, we referred to these estimates as "women in need" of contraceptive services and supplies generally, or of publicly supported contraceptive services and supplies specifically. In this report, we have revised our terminology and definitions to be more explicit about what each indicator is measuring (see Key Definitions).

It is important to note that our definition of potential demand for contraceptive care may include some women who do not actually want and will not seek contraceptive care. For some women, pregnancy intentions or desires are fluid and can change, even within a short period of time.8 Our estimates represent the total number of women who could potentially seek contraceptive services during the year to prevent a pregnancy that they would like to postpone or avoid (regardless of whether they obtain care).

It is also important to note that our definition of likely need for public support for services is based on income level and age and represents eligibility for public support at Title X–funded clinics. However, many women who fit this definition have public health insurance, such as Medicaid, and a relatively smaller proportion have private health insurance. In either case, low-income women with public or private insurance often obtain care from publicly supported clinics for a number of reasons. These sites typically accept public insurance; they offer reduced-fee or free services to women who cannot use their insurance for confidentiality reasons or because it does not cover the care they want; and they provide high-quality contraceptive care.

Since 1995, we have periodically produced state- and county-level estimates of the likely need for publicly supported contraceptive services and supplies, along with data on the number of women who receive publicly supported contraceptive care. Since 2010, our reports have also included state-level information on the impact that providing publicly supported contraceptive services has on helping women prevent pregnancies and other health outcomes that they want to avoid or delay. Most recently, we published estimates for this full set of indicators at the national, state and county levels for 20107 and at the national and state levels for 2014.9 We have also published data on the numbers of women receiving publicly supported contraceptive care for 2015 at the national, state and county levels.1

This report provides updated estimates for 2016 for the following key indicators measuring the likely need for, actual provision of, and—by helping women achieve their reproductive goals—the impact of publicly supported contraceptive and related sexual and reproductive health services:

- The numbers of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies according to age, income level, race and ethnicity, and health insurance status.

- The numbers of women who received contraceptive services at all publicly supported family planning providers, including those served at publicly supported clinics and Medicaid enrollees served by private providers.

- The numbers of reproductive health outcomes prevented among women who received publicly supported contraceptive care, such as pregnancies that they would have wanted to postpone or avoid, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), abnormal cervical cell or cervical precancer cases, and cancer, as well as STIs prevented among women and their partners through testing and vaccines provided in publicly supported family planning settings.

- The cost savings in public funds that result from preventing negative health outcomes.

This report highlights national-level findings and trends, and includes summary tables of national and state data.

Methodology

Key Definitions

We used the following definitions in our analyses:†

- Women are counted as having a potential demand for contraceptive services and supplies if they are aged 13–44 and meet the following three criteria:

(1) they have ever had voluntary penile-vaginal intercourse;‡

(2) they are able to or believe they are able to conceive (we include women for whom neither they nor their partner(s) have been contraceptively or noncontraceptively sterilized, and who do not believe that they are unable to conceive for any other reason); and

(3) they are neither pregnant nor trying to become pregnant during all of the given year.

- Women likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies if they meet the above criteria and are aged 20 or older with a family income below 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL; less than $50,400 for a family of three in 2016) or are younger than 20. All adolescents who have a potential demand for contraceptive services, regardless of their family income, are assumed to have a likely need for public support because of their heightened need for confidentiality in obtaining care (which may not be provided if they depend on their family’s resources or private insurance). The income level used in this definition of likely need was set based on Title X eligibility guidelines, which classify patients whose income is under 250% of FPL as eligible for reduced-fee services. Patients whose income is under 100% of FPL (less than $20,160 for a family of three in 2016) are eligible for free services. Eligibility for adolescents is based on their own (not their parents’) resources, so most are eligible for free services. It is important to note that other public programs, such as Medicaid, use different income levels in their eligibility criteria that are set by state policy and are typically lower than 250% of FPL. To accommodate variation in how these estimates are used, we present detailed income-level groups that allow users to estimate likely need for public support for services according to income levels that may be different from the ones used here.

- A publicly supported clinic is a site that offers contraceptive services to the general public and uses public funds (e.g., federal, state or local funding through programs such as Title X, Medicaid or the federally qualified health center program) to provide free or reduced-fee services to at least some patients. Sites must serve at least 10 contraceptive patients per year. These sites are operated by a diverse range of providers, including public health departments, Planned Parenthood affiliates, hospitals, federally qualified health centers and other independent organizations. In this report, these sites are referred to as "clinics"; other Guttmacher Institute reports may use the synonymous term "centers."

- Private health care providers may offer publicly supported contraceptive services to women who are enrolled in Medicaid or other state-sponsored public health insurance programs. This care is typically provided in a doctor’s office and involves physicians as well as other types of clinicians.

- A female contraceptive patient is a woman who made at least one visit for contraceptive services during the 12-month reporting period. Sites were asked to report the number of all unduplicated female patients who made at least one visit and received any of the following services: a medical examination related to the provision of a contraceptive method; contraceptive supplies only (after an initial visit); contraceptive counseling and a method prescription, while deferring a medical examination; or a nonmedical contraceptive method, even if a medical examination was not performed, as long as a patient chart was maintained. Among clinics, a small proportion of patients who paid for their visit using private insurance or who paid the full fee for services because their income was above the threshold for free or reduced-fee services are counted among the total number of contraceptive patients served. Among private providers, only contraceptive patients who paid for their visit using Medicaid are counted.

- We use the terms female and women to refer to individuals who may have the ability to become pregnant. The data sources used in our analyses (detailed below), from which these designations originated, do not provide any further detail on the sex or gender identity of respondents. For example, our estimates of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care are based on individuals’ self-identification as women on the U.S. census and on the National Survey of Family Growth and our estimates of women who received publicly supported care are based on providers reporting the number of individuals who are classified as female in their patient data systems.

Estimating Likely Need for Public Support for Contraceptive Services and Supplies

We estimated the number of U.S. women in 2016 with a potential demand for contraceptive services and supplies and who likely need public support for this care by age and by income level, using three data sources:

1. U.S. Census Bureau reports for the number of women in each U.S. county in 2016, by age-group (13–17, 18–19, 20–29 and 30–44) and by race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other or multiple races10);

2. Analysis of the 2014–2016 American Community Survey (ACS) to obtain distributions of women according to marital status (married and living with husband or not married) and family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL; less than 100%, 100–137%, 138–199%, 200–249% and more than 250%) for each age-group by race and ethnicity;11–16 and

3. Analysis of the 2011–2015 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to estimate the proportion of women who have a potential demand for contraceptive services (because they were sexually experienced, able to conceive, and not pregnant or trying) for each demographic group (by age, race and ethnicity, marital status and income level as a percent of FPL).

Estimates were produced by combining 2016 population data from the U.S. Census Bureau with information on income level and marital status from the 2014–2016 ACS and characteristics of women from the 2011–2015 NSFG. We calculated the proportion of women in various population groups who met the specified criteria (detailed above in Key Definitions) indicating their potential to seek contraceptive services and supplies during the year using the 2011–2015 NSFG, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of 11,300 women aged 15–44 conducted by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. The proportion of women with the potential to seek contraceptive services in population groups defined by each age by marital status by income level by race and ethnicity group were then applied to county-level estimates of the number of women in each of these population groups. Estimates were made at the county level and then summed to obtain state and national estimates. For further explanation of this methodology, see the Methodological Appendix.

Women Served at Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinics

We estimated the number of U.S. women who received contraceptive services and supplies at publicly supported family planning clinics in 2016, at both state and national levels, using multiple sources:

1. The number of women receiving contraceptive care at Title X–funded family planning clinics was drawn from 2016 Title X program data, tabulated by state, excluding men and those served in U.S. territories.17 These clinics accounted for 58% of all female contraceptive patients served at family planning clinics.

2. The number of women served at other publicly supported clinics—those clinics that do not receive Title X funds—was estimated by starting with published state tabulations of women served by such clinics in 2015 (the most recent year available).1 We then projected the state-level change in the number of patients served at these sites between 2015 and 2016 using data from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) on the number of women aged 15–44 who were served in 2015 and 2016 at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs).18 We calculated the percentage change between years using the HRSA data and applied the state-level percentage change to the 2015 number of contraceptive patients served in each state to estimate the number served in 2016. Because women served at FQHCs constitute nearly half of all women served at non-Title X–funded clinics (48%), we reasoned that this projection method was the best method available.

For further detail, including the detailed methodology for collecting 2015 data on patients served, see the Methodological Appendix.

Women Receiving Medicaid-Funded Contraceptive Services from Private Providers

We estimated the national number of women receiving Medicaid-funded contraceptive services from private providers using information from the 2011–2015 NSFG19 on the type of provider respondents reported visiting for contraceptive services and how they reported paying for their visit. Among the 25 million women who reported receiving at least one contraceptive service in the prior 12 months, 73% (18.7 million women) reported receiving that care at a private provider’s office; 17% (3.2 million women) of those who went to a private provider reported that their contraceptive visit had been paid for by Medicaid. A previous report7 used data from the 2002 and 2006–2010 NSFG to make similar estimates for 2001 and 2010. Recent analyses of the 2011–2015 NSFG uncovered some inconsistencies in how women report their insurance status and their payment source for contraceptive services. To account for these inconsistencies, we constructed a corrected payment source variable for the current analysis. To be consistent across years, we have revised our 2001 and 2010 estimates of the number of women using Medicaid for contraceptive services at private providers based on the corrected payment source variable, and these numbers are somewhat higher than the previously published numbers. There are no data available to estimate the number of women who receive Medicaid-funded contraceptive services from private providers by state.

Extent to Which Publicly Supported Providers Are Meeting Likely Need for Care

We estimated the extent to which current providers are meeting the likely need for public support for contraceptive care as the ratio of the number of female patients receiving publicly supported contraceptive services to the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies.

It is important to note that these estimates cannot be used to derive a measure of "unmet need" for publicly supported contraceptive care. Some women who likely need public support for contraceptive services, but who are not counted here, may have obtained contraceptive services or methods from other sources (including pharmacies or private providers) that they pay for out of pocket or through private health insurance.

National estimates of the extent to which potential demand for publicly supported contraceptive care is met include all women receiving contraceptive care from publicly supported clinics, as well as Medicaid patients who received such care from private providers. State estimates represent the extent to which potential demand is met by publicly supported clinics only.

Impact of Services Provided During Publicly Supported Family Planning Visits

Pregnancies avoided or postponed. Services provided during publicly supported family planning visits help women achieve the reproductive health outcomes they desire, including avoiding or postponing pregnancy. We estimated the numbers of pregnancies that were postponed or avoided by the provision of publicly supported contraceptive services in 2016 using methodology that is comparable to previous analyses.20–22

We began with the total numbers of adult and adolescent female contraceptive patients served (including patients served at publicly supported clinics and Medicaid recipients who received contraceptive services from private providers). We adjusted these numbers based on the fact that some patients served do not obtain or use a contraceptive method. In 2016, 86% of women served at Title X clinics reported current use of a contraceptive method.17 We assumed that this same percentage applied to all clinics and to private providers serving Medicaid recipients and estimated the total number of method users who received publicly supported contraceptive care in 2016 to be 86% of all patients served and 86% of adolescent patients served.

Next, we estimated the total number of pregnancies avoided or postponed in 2016 for all women, and for adolescents separately, by multiplying the number of method users—nationally and in each state—by the ratio of pregnancies prevented per 1,000 method users. This ratio was updated for this analysis and is estimated to be 249 pregnancies prevented per 1,000 method users. A summary of the steps taken to calculate this ratio are listed below. Details for each step can be found in the Methodological Appendix.

- Examined the actual contraceptive method-mix distribution for a national sample of recipients of public-sector family planning services.19

- Compared actual use with an estimated hypothetical method-mix distribution scenario for these women in the absence of publicly funded services. The hypothetical scenario is based on measuring the method mix of similar women who did not use publicly funded contraceptive services in the prior year, but had the potential to use these services in the future.

- For both actual use and the hypothetical scenario, estimated the number of pregnancies that each group would experience in one year based on their method-mix distribution and the one-year typical contraceptive failure rates for each method23 (each estimated separately for women by age, race and ethnicity, income level and marital status). Expected pregnancies were further discounted based on the difference between the number of pregnancies predicted using one-year typical contraceptive failure rates and the documented number of pregnancies actually experienced by all contraceptive method users in the United States in 2013. This adjusts for the fact that not all women use their method for an entire year and for the fact that women who have used their method for longer than 12 months may have failure rates that are lower than the rates experienced during the first year of method use.

- For both actual use and the hypothetical scenario, we then estimated the number of pregnancies expected per 1,000 public-sector family planning patients.

- Finally, we computed the number of pregnancies prevented per 1,000 women by subtracting the number of pregnancies expected among current patients from the number of pregnancies expected under the hypothetical scenario that would occur in the absence of publicly funded services.

Using the resulting estimate for pregnancies prevented, we classified pregnancies by expected outcome based on the most recent national data on observed outcomes in each category.24 Overall, we estimated that 47% of pregnancies in 2016 conceived when women would have rather avoided or delayed them resulted in a birth, 34% in an elective abortion and 19% in miscarriage; for adolescents, those proportions are 52%, 29% and 19%, respectively.

Negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes prevented. We also estimated the impact of testing for STIs and HIV, as well as routine gynecologic care such as Pap and HPV tests and HPV vaccines, during publicly supported contraceptive visits. These services, along with treatment provided on-site or by referral for patients who test positive, prevent a range of negative outcomes among women (including PID, abnormal or precancer cases, and cancer) and their partners (including STIs, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea, and HIV).

We began this analysis by estimating the number of women we expected would forgo preventive sexual and reproductive health care if they lost access to publicly supported contraceptive services. These estimates were based on the same hypothetical scenario of similar women described above. We assumed that all women in the hypothetical scenario who continued to use short-acting prescription methods (10% were calculated to use pills, patch, injectable or ring) would also continue to receive preventive services. For women who might switch to a nonprescription or no method or continue to use their long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method and therefore would not necessarily make a visit for contraceptive services, we looked at similar women in the NSFG19 and found that among this subgroup, 21% received a preventive gynecologic service (made a visit that included a Pap test and/or pelvic exam) during the year. Combining these findings, we estimated that 28% of women would continue to get preventive care if they lost access to publicly supported services, but 72% would not. For the small number of men who receive care from publicly funded clinics (the majority of whom receive STI services), we assumed that all of them would forgo preventive services in the absence of public support for that care.

A brief summary of the key steps for estimating outcomes prevented follows. Further details are included in the Methodological Appendix.

- Chlamydia and gonorrhea testing. We estimated the proportion of women and men who would forgo testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea using data on the proportions currently tested at Title X clinics.17 State-level data on the proportions of family planning clinic patients who tested positive for chlamydia or gonorrhea came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).25,26 From these data, we estimated state-specific measures for the proportion of patients who would have a positive chlamydia or gonorrhea test among those receiving services at Title X–supported family planning clinics and applied these proportions to the numbers of patients estimated to forgo care who were served at all clinics and by private providers for women on Medicaid. We used information from other researchers to estimate treatment rates and the likelihood of specific health outcomes, such as PID, in the absence of treatment. In addition, we estimated the number of infections that would have been prevented among the partners of patients who received testing during publicly supported contraceptive visits and the outcomes from preventing those infections.

- HIV testing. We estimated the proportion of women and men who would forgo testing for HIV using data on the proportions currently tested at Title X clinics.17 Data on the proportion who would have a positive test came from both Title X patient data and from the CDC.27 We applied this information to the numbers of patients estimated to forgo care who were served at all clinics and by private providers for women on Medicaid. Further adjustments and estimates of the number of HIV infections that would have been prevented among the partners of patients testing positive were based on information from other researchers.

- Cervical cancer testing and prevention. We estimated the proportion of women who would not have received Pap and HPV testing and vaccinations had they forgone care at all clinics and from private providers for women on Medicaid. For the testing analysis, we used data on the proportion of female patients who obtained a Pap test at Title X clinics17 as a proxy for the proportion tested at all publicly funded clinics. We combined that information with data on patients who would have received a Pap test alone and those who would have received both Pap and HPV testing, according to data from a survey of U.S. family planning clinics.28 To estimate numbers of cervical cancer cases and deaths prevented, we then applied information on the incidence of cervical cancer cases and deaths to patients with and without testing and under different testing scenarios29 that matched U.S. cervical cancer screening guidelines.30 For the prevention analysis, we used the ratio of the number of HPV vaccines administered to the number of female patients seen at Planned Parenthood clinics nationally in 201631,32 as a proxy for the ratio of vaccinations provided at all publicly supported family planning clinics. We used published estimates of the number of abnormal Pap tests, precancerous lesions, cervical cancer cases and cervical cancer deaths per 100,000 women vaccinated33 to calculate the number of events averted among the population receiving services at publicly supported family planning facilities. We used published data on the number of other HPV-attributable cancers (including vulvar, vaginal, anal/rectal and oropharyngeal cancers) prevented by vaccination34,35 to estimate the number of cancer cases prevented.

Public cost savings. Helping women and couples achieve their reproductive goals and avoid negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes improves the lives of women and their families in many ways. In addition to the health and personal benefits that derive from publicly supported contraceptive services, there are public cost savings from helping people realize their reproductive goals and avoid negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Specifically, we estimated the public costs for medical care that would have been incurred in the absence of publicly funded family planning services as:

- Medicaid costs associated with prenatal care, delivery, postpartum care and medical care for children through five years old for pregnancies that were averted by women’s use of contraception; and

- Medicaid costs associated with adverse health outcomes for women and their partners that would have occurred in the absence of STI testing or HPV testing and vaccines received at family planning visits.

After summing these costs to obtain gross cost savings, we subtracted the estimated total public cost used to provide family planning services in publicly supported settings to obtain net cost savings. Total public costs for family planning services were estimated by calculating the state-level public revenues per patient (including federal funds from Medicaid and Title X, as well as other federal, state and local funding) used to support the provision of services at Title X clinics. For 2016, the national average public cost for family planning services was estimated to be $316 per patient. Details of these calculations can be found in the Methodological Appendix.

Table Notes

- This report is the source for all 2016 data in the accompanying tables and figures. Data for earlier years (numbers of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies in 2000, 2006 and 2010, and numbers of contraceptive patients served in 2001, 2006, 2010 and 2015) have most recently been provided in our 2010 and 2015 reports.1,20

- All population and patient estimates; numbers of pregnancies, births and abortions averted; and most estimates of the number of adverse health outcomes avoided through STI and HPV testing and vaccines have been rounded to the nearest 10. State and population group totals, therefore, do not always sum to the national total.

- Racial and ethnic group totals do not sum to the overall total on state-level tables because the group of women reporting other or multiple races is not shown separately, although it is included in the overall total. Our methodology for estimating numbers of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies is based on estimating the proportion of women according to multiple demographic characteristics and their likely need for publicly supported care using the NSFG and applying those proportions to county-level census data; therefore, it is not possible to look separately at groups with small numbers of women, such as those who identify as indigenous or Asian and Pacific Islander.

Likely Need for Public Support for Contraceptive Services

Information on patterns and trends in the numbers and characteristics of women who may need public support for contraceptive care is critical for the design and implementation of public policies and programs aimed at providing all women with access to the care they desire and that will help them best meet their reproductive goals and preserve their sexual and reproductive health. This information can also be compared with the numbers of women who obtain care from various types of providers who offer publicly supported services to better understand service delivery patterns and to identify gaps in care. Our estimates measure the potential demand for publicly supported contraceptive services and supplies over the course of one year (see Key Definitions).

- In 2016, 20.6 million U.S. women were likely in need of public support for contraceptive services and supplies (Tables 1 and 2).

- Some 16 million women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies were adults living below 250% of FPL; 6.2 million of these women had incomes below 100% of FPL.

- Young women aged 13–19 accounted for more than one-quarter (4.6 million) of those who likely need public support for contraceptive services, due to their limited financial resources and the increased likelihood that they desire confidential care without having to depend on their families’ resources.

- Of all women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies, 10.1 million were non-Hispanic white, 3.7 million were non-Hispanic black, 5.1 million were Hispanic, and 1.8 million were members of other or multiple racial and ethnic groups.

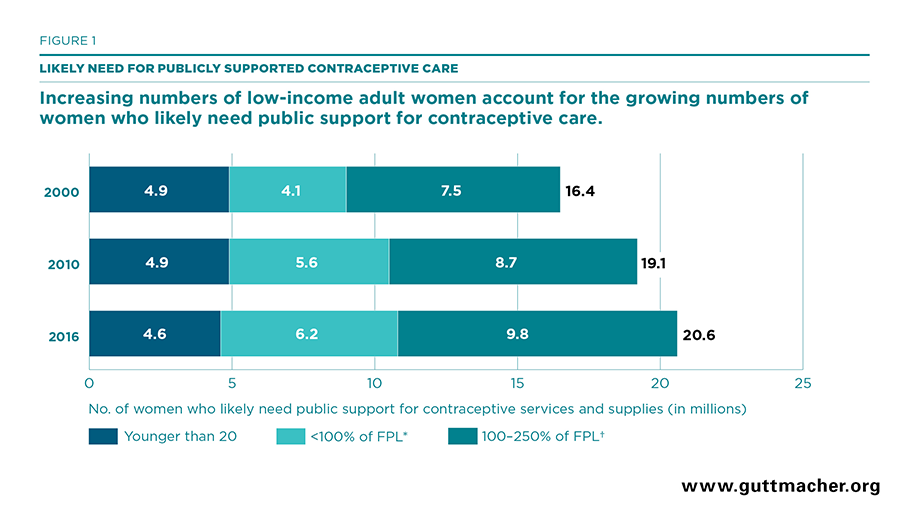

Trends. Overall, the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care increased by 25% over the past 16 years, rising from 16.4 million women in 2000 to 19.1 million in 2010 and to 20.6 million women in 2016. The extent of the increase has varied over time, as well as across social and demographic groups (Tables 1–3 and Figure 1; see also Appendix Tables A–D for data on all women with potential demand for contraceptive services and supplies).

- Between 2010 and 2016, the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care rose by 8%—an increase of 1.5 million women.

- Over this period, likely need rose the most among adult women over age 30 (14%) and among those with family incomes below 250% of FPL (12%); the number of adolescents who likely need public support for contraceptive services fell by 5%, from 4.9 million women in 2010 to 4.6 million in 2016.

- The number of Hispanic women who likely need public support for contraceptive care increased by 11%; likely need increased by 10% for black women and by 5% for white women.

State variation. Most states experienced an increase between 2010 and 2016 in the numbers of women likely needing public support for contraceptive care (Table 4).

- Seventeen states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia) and the District of Columbia experienced a 10% or greater increase between 2010 and 2016 in the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services or supplies. Four of these states (Florida, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Texas) experienced a 15% or greater increase.

- Only three states experienced declines in the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care during this period (Hawaii, Maine and New York), although these decreases were small (1–4%).

Number uninsured. Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has provided many Americans with access to health insurance that was previously out of reach—including both public insurance through the federal-state Medicaid program and private insurance purchased through the ACA’s health insurance marketplace (which includes federal subsidies for many low-income individuals36). As a result, the numbers of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who were uninsured fell dramatically between 2010 and 2016, with most of the change happening between 2013 and 2016, coinciding with the period in 2014 when most of the ACA’s major coverage expansions went into effect (Table 5).

It is again important to note that our estimates of the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services are based on their eligibility for such care at Title X–funded clinics and do not take into account whether they have public or private health insurance coverage. Many women have public coverage such as Medicaid, some have private coverage that is subsidized through the insurance marketplace and some have private coverage from an employer that may or may not cover contraception and may or may not ensure confidentiality. Thus, publicly or privately insured women may still choose to obtain care from publicly supported clinics, both because these are places where they know they can go for high-quality, confidential contraceptive care, and also because they can still obtain free or reduced-fee care if they are unable to use their insurance. Currently, we cannot estimate precisely how many of the insured women who fit our definition of having a likely need for public support for contraceptive care have public versus private health insurance. However, we do know that among all women of reproductive age whose family income is under 100% of FPL, nearly half (49%) were covered by Medicaid in 2016 compared with 27% who had private insurance.37

- Between 2013 and 2016, both the number and proportion of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who had neither public nor private health insurance fell dramatically—from 5.6 million (28%) to 3.6 million (17%), a decline of 36%.

- Among adolescents who likely need public support for contraceptive care, most of the change in insurance status occurred earlier than for adult women, with the proportion uninsured falling from 15% in 2010 to 11% in 2013, and to 7% in 2016. The drop in the proportion uninsured, combined with the overall drop in the number of adolescents in this category, resulted in a decline in the number of uninsured adolescents who likely need public support for contraceptive care, from 746,700 in 2010 to 339,460 in 2016.

- Among all adult women who likely need public support for contraceptive care with a family income below 138% of FPL (the income eligibility ceiling for Medicaid in states that expanded the program under the ACA), 39% (3.1 million women) were uninsured in 2010 and 36% (3.2 million women) in 2013. This proportion fell to 23% (2.0 million women) in 2016, representing a 36% drop since 2010 in the number of women uninsured.

State variation in insurance status. States varied widely in terms of the proportion of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies who were uninsured, and in the level of change experienced between 2013 and 2016 in the proportions uninsured (Table 6). Most notably, between 2013 and 2016, there was generally a much larger drop in the proportions of uninsured women who likely need public support for contraceptive care in those states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA compared with states that did not.

- Among all states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA by the end of 2016, the number of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who were uninsured fell 50% between 2013 and 2016 (from 25% to 13%). In contrast, among all states that did not expand Medicaid, the number of similar women who were uninsured fell only 18% between 2013 and 2016 (from 32% to 25%).

- In eleven states (Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Rhode Island, Vermont and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia, the proportion of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who were uninsured in 2016 was 10% or less, and all of these states expanded Medicaid under the ACA.

- In four states (Alaska, Georgia, Oklahoma and Texas), the proportion of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who were uninsured in 2016 was 25% or higher; the state with the highest proportion uninsured was Texas (36%). These states were among those with the highest proportions of women who likely need public support for contraceptive care who were uninsured in 2013, and only one of the four (Alaska) had expanded Medicaid under the ACA by the end of 2016.

Availability of Publicly Supported Contraceptive Services

Across the United States, publicly supported contraceptive care is provided by thousands of clinics that receive public funding through a variety of federal, state and local sources. These clinics include health departments, hospital outpatient clinics, FQHCs, Planned Parenthood clinics and facilities run by other organizations. In addition, women who are eligible for and enroll in Medicaid often obtain publicly supported contraceptive care from private providers.

Providers of publicly supported contraceptive care vary widely in terms of the number of contraceptive patients served per year and whether the provider is focused on the provision of sexual and reproductive health care or provides these services in the context of a wide offering of primary care services. Clinics that focus on sexual and reproductive health services often provide a broader mix of contraceptive methods, allowing women more choice in finding the method that is best for their situation, whereas clinics that focus on primary care often provide a more limited number of contraceptive methods. Women who obtain publicly supported care from either clinics or private providers typically receive a variety of services, including contraceptive counseling and methods; preventive gynecological care such as screenings for cervical cancer, chlamydia and gonorrhea; and treatment and referrals as needed.

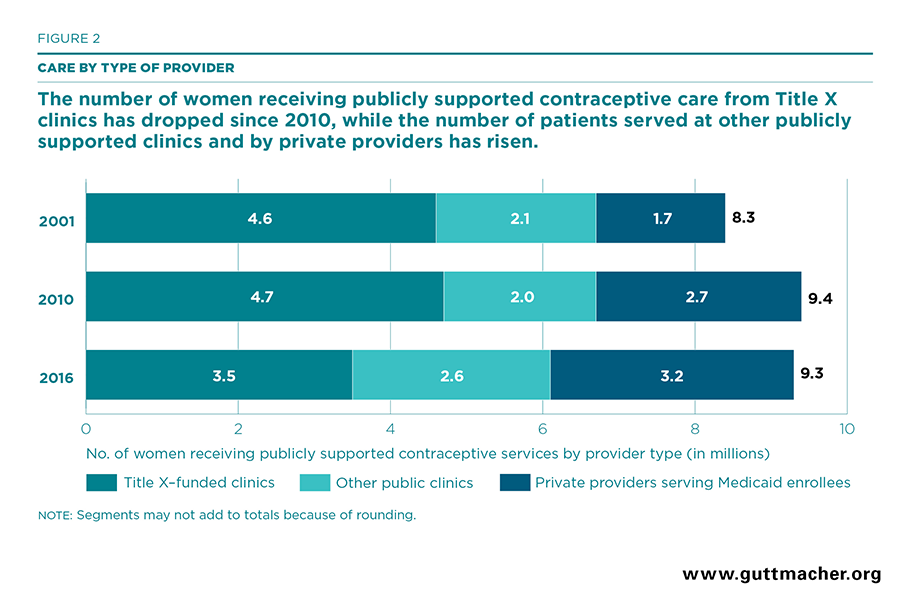

Women Served by Publicly Supported Providers

In 2016, an estimated 9.3 million women received publicly supported contraceptive services from all sources (Table 7 and Figure 2). The majority—an estimated 6.1 million contraceptive patients—were served at publicly funded clinics; an estimated 3.2 million women received Medicaid-funded contraceptive care from private providers. Among women served at clinics, 58% (3.5 million§) were served at Title X–funded clinics and 42% (2.6 million) were served at publicly supported clinics not funded by Title X (Table 8).

- In 2010 and 2016, the overall number of women who received publicly supported contraceptive services from all providers was nearly the same—9.4 million women served in 2010 and 9.3 million in 2016.

- However, the number of women served by different types of providers shifted dramatically over this six-year period. The number of contraceptive patients served by Title X–funded sites fell by 25%, from 4.7 million in 2010 to 3.5 million in 2016. In contrast, the number of contraceptive patients served by other public clinics that do not receive Title X funding rose by 29% (from 2.0 to 2.6 million) and the number of women receiving Medicaid-funded contraceptive services from private providers increased by 19% (from 2.7 to 3.2 million).

- Data from the federal Office of Population Affairs17 indicate that most of the drop in Title X clinic patient numbers occurred between 2010 and 2014, with declines of 4–10% each year. Between 2014 and 2016, the annual declines have been more modest at 2–4%.

- The majority of states (42) experienced a drop or no change in the number of female contraceptive patients served at publicly funded clinics between 2010 and 2016; eight states (California, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia experienced an increase.

- Overall, the number of adolescent women served at all publicly supported providers fell slightly (7%) between 2010 and 2016, from 2.0 million to 1.9 million (Table 9). However, where adolescent women were served shifted considerably. The number of adolescent women served by Title X clinics fell steeply, dropping 41% (Table 10), while the number of adolescent women on Medicaid who were served by private providers rose by 22%.

Proportion of Women with Likely Need Served by Publicly Supported Providers

Comparing the number of women who obtained contraceptive care from publicly supported providers with the number of women who likely need such care is useful for understanding trends in access to care and variation in access across geographic locations. Due to the measurement of likely need (which includes some women who may have obtained contraceptives without public funds from private providers or over the counter and others who may have decided not to use contraception, despite not planning to become pregnant), we would never expect publicly supported providers to serve 100% of such women. However, looking at variation in the proportions served across time and location can help to identify patterns and gaps in access to care.

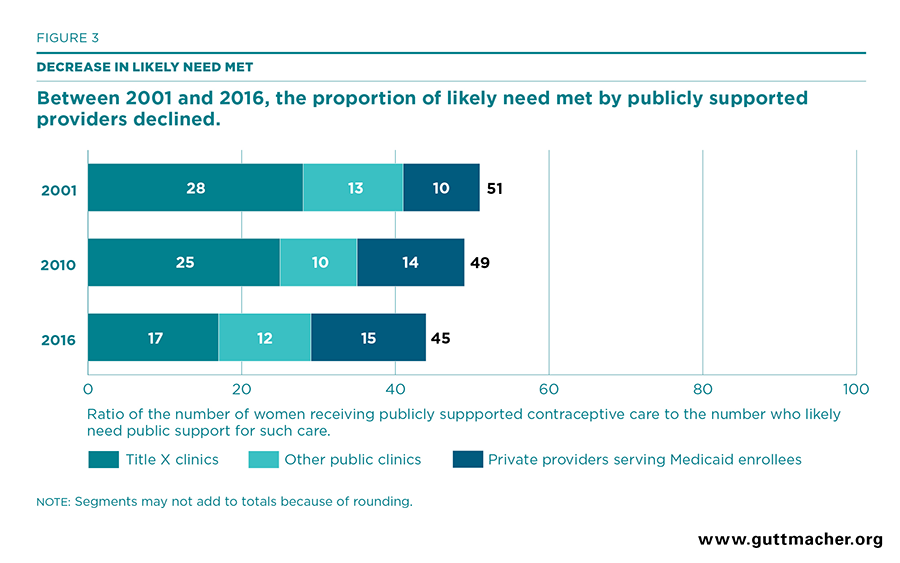

In 2016, publicly supported providers served 45% of women who likely need public support for contraceptive services, with more than nine million of the 21 million women who likely need care served. Seventeen percent of likely need was met by Title X–supported clinics, 12% by publicly supported clinics that do not get Title X funds and 15% by private providers serving Medicaid enrollees (Table 11 and Figure 3).

- Between 2010 and 2016, the overall proportion of likely need met by all publicly supported providers fell from 49% to 45%. This drop follows from the fact that the overall number of women receiving contraceptive services from publicly supported providers was similar across years, while the number of women who are likely to need public support for such care increased over the period.

- The proportion of likely need for publicly supported contraceptive care met by Title X–funded clinics fell from 25% in 2010 to 19% in 20149 and 17% in 2016. Publicly supported clinics that do not receive Title X funds met 12% of the likely need for such care in 2016, a slight increase from 10% in 2010 (Table 12).

- Overall, the proportion of adolescent women whose likely need for publicly supported contraceptive care was met by all providers remained stable at 41% in 2010 and 40% in 2016 (Table 11). However, the proportion of adolescents whose likely need for such care was met by Title X clinics fell sharply, from 22% to 14%. In contrast, the proportion of adolescents whose likely need for publicly supported contraceptive care was met by other (non-Title X–supported) clinics rose from 8% in 2010 to 12% in 2016 and the proportion served by private providers through Medicaid rose from 11% to 15% over the same period.

- The proportion of likely need for publicly supported contraceptive services met by all clinics in 2016 varied widely by state, from a low of 14% in Nevada to a high of 88% in the District of Columbia.

Impact of Publicly Supported Family Planning Services

Publicly supported family planning providers help women achieve their reproductive goals by providing access to the contraceptive services that women want. A host of benefits accrue when women and families are able to plan whether, when and how many children to have.38,39 One of the most basic benefits of these services is the prevention of pregnancies that women wish to postpone or avoid. During family planning visits at publicly funded providers, many women also receive testing for STIs and HIV, as well as routine gynecologic care such as Pap and HPV tests and HPV vaccines. These services, along with treatment provided on-site or by referral for women who test positive, prevent a range of negative outcomes among women (including PID, abnormal or precancer cases, and cancer) and their partners (STIs, including HIV, chlamydia and gonorrhea). To estimate the impact of publicly funded family planning services, we updated our estimation procedures using the most recent data available and applied updated cost information to generate new estimates of the public cost savings that come from preventing pregnancies and negative health outcomes among women whose care would have been paid for from public sources.

Contraceptive Method Use in the Absence of Publicly Supported Care

Women who obtain contraceptive services from publicly supported providers use a variety of highly effective contraceptive methods. Based on the 2011–2015 NSFG, on average, 57% rely on hormonal methods, such as oral contraceptives, injectables, the contraceptive patch and the contraceptive ring; 18% rely on long-acting reversible methods (IUDs and implants); and 7% have had a recent tubal sterilization (Figure 4). In contrast, we estimate that a hypothetical group of similar women without access to publicly supported services would switch to a much less effective mix of contraceptive methods. Only 25% would continue to use hormonal or long-acting methods, nearly half (46%) would use either condoms or other nonprescription methods, and 28% would use no method.

- For every 1,000 women using the average mix of contraceptive methods obtained from publicly supported providers, an estimated 43 will become pregnant each year.

- For every 1,000 women using the average mix of contraceptive methods estimated for the hypothetical group without access to publicly supported care, an estimated 293 would become pregnant each year.

- Comparing the estimated pregnancies occurring among each group, we conclude that for our 2016 analysis, 249 pregnancies are prevented for every 1,000 women using publicly supported contraceptive services. These hypothetical pregnancies would have occurred if women lost access to publicly supported care and switched to the less effective mix of methods.

Comparing our current analysis using the 2011–2015 NSFG with the analysis done for our 2010 report using the 2006–2010 NSFG, we find that the mix of methods obtained from publicly supported providers, as well as the mix of methods used by women in the hypothetical group, shifted toward use of more effective methods.

- For example, among women served by publicly supported providers, the proportion using LARC methods rose from 11% to 18%. Similarly, among women in the hypothetical group of contraceptive users, the proportion using either hormonal or LARC methods would rise from 15% to 25%.

- These shifts result in fewer estimated pregnancies per 1,000 women occurring both to women currently served by publicly supported providers (43 in 2016 compared with 62 in 2010) and to the group of hypothetical women without access to publicly supported care (293 in 2016 compared with 350 in 2010).

- Despite the fact that fewer women who obtain contraceptive care from publicly supported providers are expected to become pregnant, our updated estimate of the number of pregnancies that are prevented per 1,000 contraceptive users served at publicly supported providers has declined (from 288 in 2010 to 249 in 2016), because more women in the hypothetical group are expected to use more effective methods.

Benefits from Contraceptive Use

We quantified the benefits of contraceptive use to help women prevent pregnancies that they would like to postpone or avoid by applying our updated estimate of the number of pregnancies prevented per 1,000 method users served by publicly supported providers to the number of women served in 2016. These results represent the hypothetical number of pregnancies that would have occurred in the absence of publicly supported care.

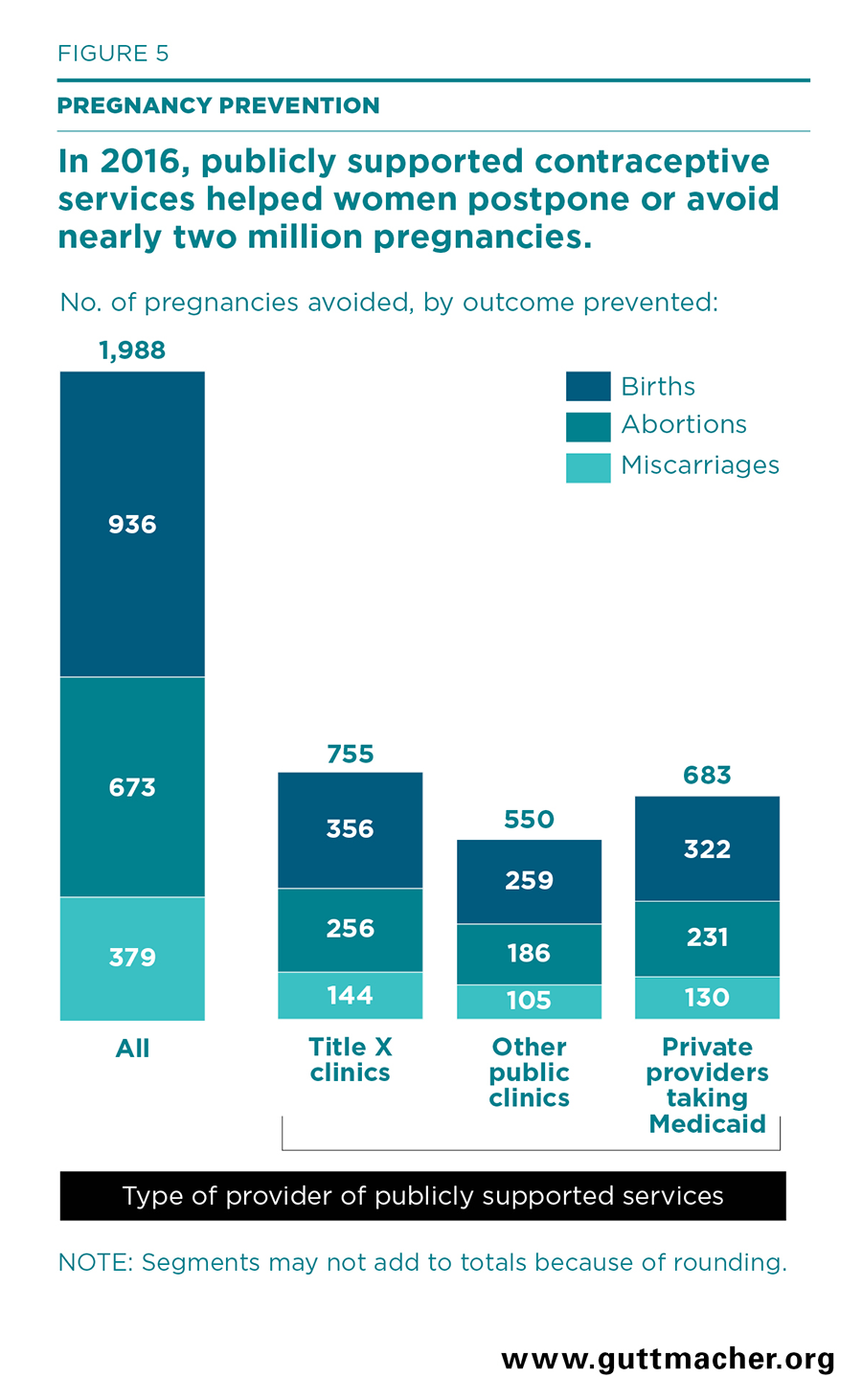

- Women who obtained contraceptives from publicly supported providers in 2016 were able to delay or avoid nearly two million pregnancies (Tables 13 and 14 and Figure 5). More than 936,000 of those pregnancies would have resulted in births and 673,000 would have resulted in abortion; the remainder would have resulted in miscarriage.

- Publicly funded clinics alone were responsible for helping women delay or avoid more than 1.3 million pregnancies in 2016, while private providers serving Medicaid recipients helped nearly 683,000 women delay or avoid pregnancy.

- Title X–funded clinics accounted for the large majority of this benefit, helping women delay or avoid 755,000 pregnancies in 2016 (Table 15). Clinics supported by other (non–Title X) public funds helped women delay or avoid 550,000 pregnancies (Table 16).

- Publicly supported contraceptive services helped more than 500,000 adolescents avoid or postpone becoming pregnant in 2016. Title X–funded clinics helped adolescents avoid 173,000 pregnancies; clinics supported by other (non–Title X) public funds helped adolescents avoid or postpone 149,000 pregnancies; and private providers who served adolescents on Medicaid helped adolescents avoid 187,000 of these pregnancies (Table 17).

Benefits from STI Testing

Screening for STIs, including chlamydia and gonorrhea, is an integral component of reproductive health services that is offered by 98% of publicly funded family planning clinics.28 Chlamydia and gonorrhea are two of the most common STIs in the United States: An estimated 2.9 million new chlamydia infections and 820,000 new gonorrhea infections occur each year.40 If left untreated, such infections can lead to a host of adverse health outcomes, including PID, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain in women and epididymitis in men.41 HIV testing is frequently provided during family planning visits; it is offered at 94% of health centers that provide publicly supported family planning services.28 It is also a preventive care service for partners of individuals who learn they are HIV-positive, because it can lead to less risky behavior after a positive test result and reduced infectivity (via earlier entry into treatment for people living with HIV38), both of which significantly decrease transmission. Details for these benefits separated by type of provider can be found in Tables 13–16.

- Approximately half of all women who made a publicly funded family planning visit in 2016 received a chlamydia test; half were tested for gonorrhea and one-quarter were tested for HIV. Among men who made a publicly funded family planning visit in 2016, more than half were tested for HIV (data not shown).

- Without access to publicly funded care for family planning services, the majority of these women (72%, or some 6.7 million women) would have forgone screening for chlamydia, gonorrhea or HIV, resulting in tens of thousands of undetected and untreated STIs.

- By identifying and treating these infections, future infections among the partners of patients can be prevented. An estimated 100,000 chlamydia infections, 18,000 gonorrhea infections and 800 HIV infections were prevented among the partners of patients in 2016 (Tables 13 and 14).

- Among the patients themselves, early treatment for those testing positive for chlamydia or gonorrhea helped to prevent more than 12,000 cases of PID, which would have resulted in more than 1,000 ectopic pregnancies and 2,000 women becoming infertile.

Benefits from Cervical Cancer Testing and Prevention

Incidence of and mortality due to cervical cancer in the United States has been declining steadily since at least the late 1990s.42 However, in 2015, more than 12,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer and about 4,000 died from the disease. Annual health care costs of screening, treating and managing cervical cancer and related abnormalities nationally have been estimated to be as high as $4.6 billion as of 2008, the most recent year for which data are available.43 Because providers of contraceptive services often provide gynecologic care that can identify and help reduce the risk of cervical cancer, we examined the impact of two services they provide—Pap and HPV testing and HPV vaccination—on the number of cases of cervical cancer and related deaths prevented. Details for these benefits separated by type of provider can be found in Tables 13–16.

- In 2016, an estimated 1.8 million women receiving publicly supported contraceptive services also received cervical cancer testing (data not shown). Without publicly supported contraceptive services, an estimated 1.3 million women would have forgone or postponed cervical cancer testing that year.

- An estimated 1,860 potential cervical cancer cases were identified by this testing and treated before cancer developed, and 850 cervical cancer deaths were prevented (Table 13).

- In 2016, about 39,000 adolescent and young adult women received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine while receiving publicly supported contraceptive services (data not shown).

- HPV vaccinations provided by publicly supported providers in 2016 helped their patients avoid an estimated 4,590 cases of abnormal cervical cells, 920 cases of precancerous lesions, 50 cases of cervical cancer and 40 cases of other HPV-associated cancers, such as anal or vulvar cancer. An estimated 20 cervical cancer deaths were prevented (Tables 13 and 14).

Cost Savings

We estimated the total medical costs for services and treatments attributable to the outcomes prevented by publicly supported family planning visits, as well as the share of these costs that would have been paid for with public funds, primarily Medicaid and Medicare. Only public costs and savings are presented. In addition, our estimates include only the public cost savings for services provided to patients (or their partners) who, in the absence of publicly supported care, would have used a less effective mix of contraceptive methods or would have delayed obtaining other preventive care services. Details for cost savings separated by type of provider can be found in Tables 13 and 18–20.

- Without publicly supported contraceptive services in 2016, the resulting pregnancies would have cost an estimated $14.3 billion in Medicaid-covered maternity and infant care and in medical care for young children through five years old (Tables 13 and 18). An additional $418,000 would have been spent on care for miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies.

- In addition, an estimated $273 million in cost savings was attributable to STI and HIV testing during family planning visits in 2016.

- An estimated $14.5 million in cost savings was attributable to HPV sequelae being identified and treated earlier because of testing for cervical cancer ($12.4 million) or prevented because of vaccines ($2.0 million).

- Collectively, publicly supported family planning services resulted in an estimated total of $15.0 billion in gross federal and state government savings in 2016.

Net Savings

We estimated the net public cost savings from publicly supported contraceptive services and related care provided during family planning visits as the difference between total gross public savings and the public cost of providing family planning services. The latter was estimated using information on the per-patient public revenues used to support family planning services at Title X–funded clinics. It is worth noting that this estimate rose considerably since our last report, from an estimated $239 per patient in 2010 to an estimated $316 per patient in 2016. The increase in the public cost of providing contraceptive services was not met with a similar increase in the cost savings generated per patient, resulting in slightly lower net savings compared with our analysis of 2010 data.

- The total public costs associated with providing family planning services in 2016 were estimated to be $3.1 billion.

- Subtracting these costs from the estimated $15.0 billion in gross public savings results in an estimated total net public savings of $11.9 billion in 2016.

- An estimated $7.7 billion of the total net savings was attributable to services provided by all publicly supported clinics, $4.4 billion of which resulted from services provided at Title X–funded clinics. Another $4.2 billion was attributable to the Medicaid-funded family planning services provided by private physicians.

- Overall, by providing patients with services to prevent or delay pregnancies and to protect against reproductive cancers and STIs, publicly funded family planning services resulted in an estimated savings of $4.83 for every public dollar invested.

Discussion

Overall trends in likely need and women served. Since 2010, the number of U.S. women who likely need public support for contraceptive services and supplies increased from 19.1 million to 20.7 million, an 8% rise. This increase can be attributed primarily to an increase in the proportion of adult women whose family income is below 250% of FPL—a trend that largely mirrors growing income disparities in the United States over the period,44 which intensified during the recession and left lasting economic consequences for women and their families. Over the same period, the number of women who received publicly supported contraceptive care remained virtually the same, resulting in a drop in the proportion of women with likely need for publicly supported care who were served (49% to 45%).

While this trend suggests that access to publicly supported contraceptive care has declined, there may be unmeasured factors, such as use of private insurance or over-the-counter contraceptives, that women are relying on to meet their reproductive goals. In fact, among women who are able to conceive, have had recent sex and are not pregnant or trying to get pregnant, 9 in 10 are using some form of contraception.45 However, the high level of contraceptive use does not necessarily mean that what women see as their own needs are being fully met. Some women who are using nonprescription methods, such as condoms, may not be using the method they would ideally use if they had better access to publicly supported care and could choose from a wide range of methods. In addition, women who rely on nonprescription contraceptive methods because they are unable to access publicly supported care may also forgo cancer or STI screenings that they would have wanted. Publicly supported family planning helps people more fully access and afford the services they want, in order to meet what they see as their own needs.

Network changes in publicly supported contraceptive care. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of U.S. women receiving publicly supported contraceptive care from all provider types remained virtually unchanged at just over nine million. However, stability in the overall national numbers served masks unprecedented change in where U.S. women receive publicly supported contraceptive care. The share of all women served who went to Title X–supported clinics fell from 50% in 2010 to 38% in 2016. In contrast, the share of women served by other (non–Title X) publicly supported clinics rose from 21% to 28% and the share of women served by private providers rose from 29% to 34%.

Many competing factors are likely contributors to change in the publicly supported provider network and key among these are shifting public funding streams. Between 2010 and 2016, federal appropriations to the Title X program fell from $317 million to $286 million;46 this was a 10% drop in unadjusted dollars, but a decrease of 25% when adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index for medical care. Also, in many states and communities, shrinking state budgets, as well as targeted reductions in funding for specific programs or grantees, have led to clinic closures and reductions in clinic services, especially among Title X–funded sites.

In contrast, federal appropriations for community health centers, authorized under Section 330 of the Public Health Services Act, more than doubled during this period, from $2.4 billion in 2010 to $5.1 billion in 2016.47 These funding increases are important for understanding the rise in both the number of FQHCs providing contraceptive care and the numbers of contraceptive patients served. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of FQHCs providing contraceptive services increased from 3,165 to 5,829, an 84% increase; the numbers of contraceptive patients served rose 78%.1 Currently, approximately half of all women receiving contraceptive care from non–Title X publicly supported clinics receive services from FQHCs. The vast majority of FQHC sites serve a disproportionately small number of contraceptive patients per year (320 compared with an average of 580 for all clinics and nearly 3,000 for Planned Parenthood clinics), and they often do not provide patients with a full range of contraceptive method choices.28

Also, implementation of the ACA has decreased the number of low-income women who are uninsured, with many more women now eligible for and covered by Medicaid, particularly in states that implemented a Medicaid expansion under the ACA. Increases in the proportions of low-income women covered by public health insurance coincided with increases in the numbers of Medicaid recipients who received publicly supported contraceptive care from private providers, which rose 19% between 2010 and 2016. Among adolescents who likely need public support for contraceptive care, the shift away from clinics and toward use of private providers appears to be due both to increased numbers being covered by and using public insurance (Children’s Health Insurance Program/Medicaid) and to an increased willingness or ability of these patients to use their private health insurance to cover contraceptive visits at private providers.48

Further research is needed to fully understand the factors related to the changes in where women go for publicly supported contraceptive care and the consequences of these changes. The federal Title X family planning program remains critical to the provision of clinic-based contraceptive care. And, although there has been a significant decline in the number of patients served at Title X–funded clinics, these sites continue to serve more women than either clinics not funded by Title X or private providers serving Medicaid recipients. Moreover, despite funding cuts, individual Title X–funded clinics typically serve more contraceptive patients per year than do other clinics.28 They offer their patients a greater variety of contraceptive methods, do more to facilitate method initiation and consistent method use, are more likely to advise patients about contraceptives during annual gynecologic visits, and spend more time counseling patients about contraception and sexual health.28,49,50 In comparison, women who receive care from clinics that do not receive Title X funding are typically provided with a more limited choice of contraceptive options or a more limited scope of reproductive health care services. Given the increasing importance of these providers in serving women’s contraceptive and reproductive health needs, it is important that they receive support and guidance in how to better meet the full scope of what women want from a contraceptive service provider. Notably, the federal government has played an important role in creating guidelines for the provision of quality family planning services51 that can be used by both public and private providers to ensure that best practices are followed by all contraceptive service providers.

Impact of publicly supported contraceptive care. Numerous health benefits accrue to women and their families when women are provided with the contraceptive and reproductive health services they desire. Key among these benefits is the prevention of pregnancies that women wish to postpone or avoid. Overall, in 2016, women obtaining publicly supported contraceptive services were able to avoid or postpone nearly two million pregnancies. These same women and their partners were able to avoid thousands, and in some cases tens of thousands, of STI infections, PID and cancers because of the care received during publicly supported family planning visits.

By helping women determine for themselves whether and when to have children and providing them with related health services, publicly supported providers generate benefits for both women and their families, as well as for society more broadly through government cost savings. These benefits accrue because the vast majority of patients who would have become pregnant or who would need treatment for STIs, HIV and cancer would be eligible for Medicaid coverage and their medical expenses would be paid for from public funds. On average, in 2016, we estimate that serving each contraceptive patient cost $316 in public funds; in comparison, $22,122 was spent on each Medicaid-funded birth (including prenatal care, delivery, postpartum care, and infant and child medical care through 60 months) and hundreds of thousands were spent on each patient needing HIV or cancer treatment. After accounting for the estimated public costs for all events prevented and subtracting the public costs to provide family planning services, we estimate that in 2016, all publicly supported providers generated a total of nearly $12 billion in net government savings. This translates to an estimated $4.83 saved for every $1 spent on contraceptive care for women who want this service, but are unable to afford it on their own.

Measurement of these health benefits and their cost savings follows the same methodology as in past reports and has a number of limitations. Many of these are explained in detail in a previous publication21 and in the Methodological Appendix. Throughout the analysis, we have tried to use the best available parameters from published literature to model the broader impact of services, and to follow the more conservative calculation option whenever multiple options were available. It is important to note that neither the health benefits nor the cost savings estimated in this analysis represent the complete impact of the U.S. family planning effort. For example, no benefits are estimated for many common services, including counseling and education, breast exams or screening for high blood pressure; the analysis also does not extend beyond medical benefits and cost savings.

There are some important differences in the results presented here compared with our 2010 analysis. Although the numbers of events averted and their cost savings were substantial in 2016, the relative estimates of events averted per patient served and the cost savings were lower than in our analysis for 2010 (293 vs. 350 pregnancies prevented per 1,000 contraceptive users and $4.83 vs. $7.09 saved per dollar spent). The main reasons behind these changes include:

- A decline (14%) in the estimated number of pregnancies prevented per 1,000 contraceptive patients served that was, in part, due to the fact that women in our hypothetical group who would have lost access to publicly supported services would be more likely to continue to use LARC methods and therefore have fewer expected pregnancies in the absence of receiving care.

- A decline (36%) in cost savings from Pap and HPV testing and vaccines due to fewer women being tested under the revised testing protocols and also because the time from testing to cancer diagnosis is increasing, likely because of the HPV vaccine.

- A minimal increase (7%) in the estimated cost per Medicaid-covered birth ($20,720 to $22,122 for maternity, infant and child care to 60 months) that is likely due to measurement differences in maternity costs between 2010 and 2014. In each year, we used the most reliable estimates available, but as they came from different studies, the change over time represents a smaller change than is typical for medical care.

- A 32% increase in the per-patient cost of providing publicly supported services ($239 to $316). This is likely due to the increased costs necessary to provide quality family planning services, such as for LARC methods and for better screening technologies, and to serve an increasingly diverse patient population, more of whom may need language translation or other services.

In some cases, the changes in expected outcomes in the absence of care represent benefits received by women who have used publicly supported services in the past that extend for longer than one year, continuing to improve their health outcomes even without access to ongoing care. For example, the benefits of having received a LARC method or an HPV vaccine from a publicly supported provider in the past may extend to women who are not current users of publicly supported services. These are public health success stories and illustrate an unmeasured impact of publicly supported contraceptive care that extends the reach of these services. If we were able to properly measure the longer term impact of all services and ensure that such benefits did not dilute our measurement of outcomes in the absence of services, then the full range of benefits of publicly funded family planning to individuals and society would likely be even greater than what we have presented here.

FOOTNOTES

* See Key Definitions regarding our use of the terms "women" and "female" to describe experiences of individuals throughout this report.

† Some terminology used in these definitions has changed from previous reports. These changes reflect an attempt to clarify more precisely what each indicator measures; however, the methodology and data used remain the same.

‡ Estimates are based on individuals who have ever had voluntary sex, not those who have been sexually active in the past one or three months, because the intent of this indicator is to measure the potential number of women who may decide to seek contraceptive services at any time over a one-year period.

§ This total differs from the 4.0 million total Title X family planning users reported for 2016 in the Office of Population Affairs’ Family Planning Annual Report because it excludes male patients and patients served in U.S. territories.

Correction note: Changes were made to correct errors in our original estimates of the proportion of adolescents and adult women below 250% of the federal poverty level who were uninsured in 2016. Corrections were made for some state and subgroup estimates on Tables 5 and 6 and on pages 12-13 of the report, although the national estimate for the proportion of all women with likely need for contraceptive services who were uninsured did not change. None of the corrections change the study’s summary findings or conclusions.

REFERENCES

1. Frost JJ et al., Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services at U.S. Clinics, 2015, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2017, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-funded-contraceptive-services-us-clinics-2015.

2. The Alan Guttmacher Institute (AGI), Women at Risk: The Need for Family Planning Services, State and County Estimates, 1987, New York: AGI, 1988.

3. Henshaw SK and Darroch JE, Women at Risk of Unintended Pregnancy, 1990 Estimates: The Need for Family Planning Services, Each State and County, New York: AGI, 1993, https://www.popline.org/node/335121.

4. Henshaw SK, Frost JJ and Darroch JE, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 1995, with Selected Articles from Family Planning Perspectives, New York: AGI, 1997.

5. Frost JJ, Frohwirth L and Purcell A, The availability and use of publicly funded family planning clinics: U.S. trends, 1994–2001, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2004, 36(5):206–215.

6. Guttmacher Institute, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2006, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2009, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2006.

7. Frost JJ, Zolna MR and Frohwirth L, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2010, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2013, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2010.

8. Jones RK, Are uncertain fertility intentions a temporary or long-term outlook? Findings from a panel study, Women’s Health Issues, 2016, 27(1):21–28, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.10.001.

9. Frost JJ, Frohwirth L and Zolna MR, Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2014 Update, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2016, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/contraceptive-needs-and-services-2014-update.

10. U.S. Census Bureau, Annual county resident population estimates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016, June 2017, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010-2016/counties/asrh/.

11. U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey (ACS), Public Use Microdata Samples (PUMS)–CSV format, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_pums_csv_2014&prodType=document.

12. U.S. Census Bureau, 2015 ACS, PUMS–CSV format, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_pums_csv_2015&prodType=document.

13. U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 ACS, PUMS–CSV format, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_pums_csv_2016&prodType=document.

14. U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 ACS PUMS Technical Documentation, no date.

15. U.S. Census Bureau, 2015 ACS PUMS Technical Documentation, no date.

16. U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 ACS PUMS Technical Documentation, no date.

17. Fowler C et al., Family Planning Annual Report: 2016 National Summary, Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International, 2017, https://www.hhs.gov/opa/sites/default/files/title-x-fpar-2014-national.pdf.

18. Health Resources and Services Administration, 2017 health center program awardee data, no date, https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=d&year=2017&state=AR#glist.

19. Special tabulations of data from the 2011–2015 National Survey of Family Growth.

20. Frost JJ et al., Contraceptive Needs and Services, 2010: Methodological Appendix, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2013, https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/win/winmethods2010.pdf.