The United States has long served a critical leadership role in advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights around the world.1 The Trump administration—supported by social conservatives in Congress—has undermined this leadership. From making draconian funding proposals to issuing restrictive policy guidance, the Trump administration is actively undermining U.S. global health investment and the resulting progress. Congress has the power to reverse course and restore U.S. leadership—and should do so.

Current Investments

The United States provides critical global health assistance through bilateral and multilateral funding streams. Investment in three particular areas—family planning and reproductive health, maternal and child health, and HIV/AIDS—supports the advancement of sexual and reproductive health and rights in communities around the world.

USAID family planning and reproductive health program and UNFPA. Since it began in 1965, U.S. investment in bilateral family planning and reproductive health programs through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has been critical to promoting global health and well-being.2 Currently supporting efforts in more than 30 countries, the USAID family planning and reproductive health program increases access to voluntary family planning information, services and supplies. Beyond providing voluntary family planning, these programs include efforts to end child marriage, female genital mutilation and cutting, and other gender-based violence, as well as help countries address other cross-cutting factors that shape individual, family and community sexual and reproductive health and rights. As a result of the $607.5 million provided in fiscal year (FY) 2018 for U.S. international family planning and reproductive health assistance—the vast majority of which goes to the USAID family planning and reproductive health program—25 million women and couples received contraceptive services and supplies.3 That, in turn, helped them avert 7.5 million unintended pregnancies, which prevented 3.2 million abortions (of which 2.1 million would have been in unsafe conditions) and 14,600 maternal deaths.

Multilateral U.S. funding for family planning and reproductive health efforts through the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA) also plays a complementary and critical role in advancing global health and rights. UNFPA’s programming first began in 1968, and the United States played a key role in its creation. Since then, UNFPA has expanded its work to more than 150 countries. It is the world’s largest source of multilateral population assistance; its efforts often take place in humanitarian settings that are beyond the scope of USAID programming. The agency provides family planning counseling, services and supplies, as well as partnership building within communities to support adolescent health and assist people in accessing these services and achieving safer pregnancies and births. In 2017, for instance, UNFPA provided an estimated 842.5 million contraceptives, which helped prevent 13.5 million unintended pregnancies and helped avert 32,000 maternal deaths.4,5

USAID maternal and child health program. The USAID maternal and child health (MCH) program provides global leadership to improve the health and survival of women and children in low- and middle-income countries. The USAID MCH program focuses its work in 25 priority countries, 16 of which are in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region that accounts for nearly two-thirds of maternal deaths in the world each year.6–8 In these countries, the program supports cost-effective interventions such as vaccines; safe water, sanitation and hygiene; nutritional supplements; family planning information and counseling; postabortion care; and training for frontline health workers on basic prevention, treatment and management of maternal and child illnesses. In addition to its programmatic efforts, USAID MCH also supports identifying, testing and piloting technologies and innovations aimed at improving the lives of women and children.9 In 2011, for instance, in partnership with other donor countries and private foundations, USAID launched Saving Lives at Birth: A Grand Challenge for Development, which has invested in more than 100 innovations, from service-delivery approaches to diagnostics.10

In the past 10 years, USAID estimates that its MCH efforts have helped save the lives of more than five million children and 200,000 women in its priority countries.11 The United States has committed to the goal of saving the lives of 15 million children and 600,000 women in developing countries between 2012 and 2020.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) was established in 2003 with bipartisan support to ensure U.S. leadership for the global response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic.12 PEPFAR supports global HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care, and the strengthening of health systems through bilateral and multilateral programs. PEPFAR programming has helped save more than 16 million lives in more than 50 countries to date.13 By the end of 2017, PEPFAR had supported HIV testing for 85.5 million people, voluntary medical male circumcision services for 15.2 million men and boys, antiretroviral treatment for 13.3 million people and training for 250,000 new health care workers.13,14

In 2014, PEPFAR prevention efforts expanded with a new public-private partnership. The goal of the partnership is to build upon evidence-based approaches and support innovative ideas to reduce HIV infection rates among adolescent girls and young women in areas of Sub-Saharan Africa with the highest country rates of HIV.15 The DREAMS Initiative—Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored, and Safe—has reached 2.5 million young women aged 15–24 to date, supporting comprehensive HIV prevention such as testing and counseling, condom promotion and provision, and pre-exposure prophylaxis, as well as broader structural interventions, including school-based HIV and violence prevention, youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services, and community mobilization.16 According to a 2017 analysis, 65% of the communities or districts with the highest HIV burden in the 10 DREAMS countries have reduced new HIV diagnoses among young women by at least 25% since the program began.17 Last year, five more countries incorporated DREAMS-like activities into their respective PEPFAR country operational plans.

Strengthening Investments

Congress has the funding, legislative and oversight authority to ensure that the United States does not cede its leadership role in supporting sexual and reproductive health and rights around the world. Beyond protecting existing efforts, Congress should make crucial investments and pursue course corrections.

Increase U.S. funding to support global sexual and reproductive health and rights. For all of the important progress that U.S. investments have helped make possible, the work is far from over. Far too many people still have unintended pregnancies that could be avoided, acquire STIs that could be prevented or treated, and experience complications related to pregnancy and childbirth that could be averted or better managed. Every day, 400 infants are newly infected with HIV and more than 800 women—one woman every two minutes—die from largely preventable pregnancy- and childbirth-related complications.18,19 And in developing regions, 214 million women who want to avoid pregnancy for at least two years are not using a modern contraceptive method.20 These examples demonstrate how much work remains to support global sexual and reproductive health and rights.

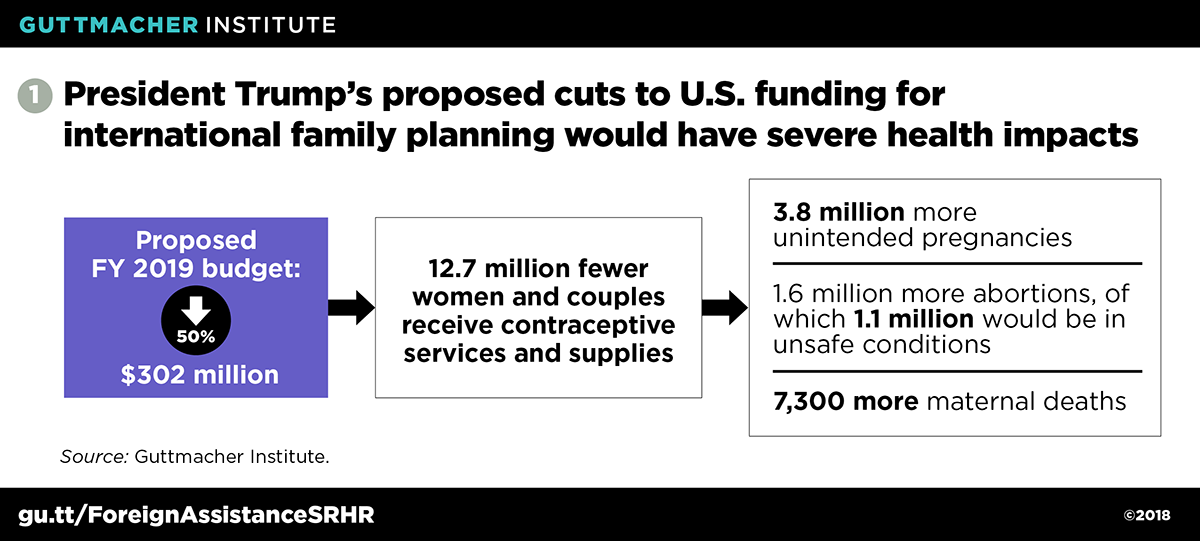

The United States cannot help reduce unmet health needs around the world without robust investment in key global health programs. Yet President Trump proposed a complete elimination of the USAID family planning and reproductive health program in his first budget, for FY 2018, a proposal that gained no traction in Congress.21 His most recent budget, for FY 2019, proposed a roughly 50% funding cut to $302 million that, if enacted, could have severe negative impacts, such as 12.7 million fewer women and couples receiving contraceptive services and supplies and 7,300 more maternal deaths in developing regions (see figure 1).22 Conversely, for every additional $10 million of U.S. investment in foreign family planning and reproductive health assistance per year in developing regions, an estimated 416,000 additional women and couples would receive contraceptive services and supplies and there would be 124,000 fewer unintended pregnancies, 53,000 fewer abortions (35,000 of which would have been provided in unsafe conditions), and 240 fewer maternal deaths.3

Instead of withdrawing from its commitments, the United States has the opportunity and responsibility to go beyond current levels of funding and contribute its fair share for international family planning and reproductive health, as set out in the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development’s Programme of Action. This agreement specifies that one-third of the financial resources necessary to provide reproductive health care should be furnished by donor countries and two-thirds by developing nations. Based on the estimated annual cost of $12.1 billion to fulfill the ongoing and unmet need for modern contraception among women in developing countries who want to avoid pregnancy,20 this agreement translates to a U.S. fair share of $1.66 billion, including $111 million for UNFPA.23 Upholding this contribution commitment would position the United States as a leader in the global effort to support sexual and reproductive health and rights in developing regions.

Repeal restrictive antiabortion policy riders. For decades, restrictions on access to abortion care have limited the reach and effectiveness of U.S. global health assistance. In 1973, Congress enacted the Helms Amendment, which prohibits foreign assistance for the "performance of abortion as method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortions."24 Further restrictions followed in the amendment’s wake, including a ban on lobbying for or against abortion, known as the Siljander Amendment.

The Helms Amendment has long been incorrectly interpreted and implemented as an outright ban on abortion, without exceptions in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest. Even in countries where abortion is legal, the application of the Helms Amendment has deterred health care providers from offering abortion-related counseling or referrals, stocking medical equipment used to treat complications of clandestine abortions (which are often unsafe), and providing safe miscarriage management and postabortion care.25,26 These harmful policies exacerbate existing health system challenges, including barriers to postabortion care, which is essential to reducing negative health outcomes resulting from unsafe abortion.27 In order to eliminate these harms, Congress should repeal the Helms Amendment and its related spin-off policy riders, such as the Siljander Amendment, in authorizing and appropriations bills.

Reverse and permanently prohibit the global gag rule. Just two days after his inauguration in 2017, President Trump issued a presidential memorandum reinstating and expanding the global gag rule. Under every Republican administration since President Reagan’s, the global gag rule has prohibited foreign organizations receiving U.S. family planning funds from providing information, referrals or services for legal abortion, or advocating for access to abortion services in their own country, even if these entities are using their own funds. In 2017, the Trump administration dramatically expanded the reach of this policy beyond foreign entities receiving family planning assistance to foreign entities receiving any U.S. global health funding.

There is no evidence that the global gag rule reduces the incidence of abortion around the world. In fact, findings from a 2011 study, the first to scientifically quantify the impact of the gag rule when it only applied to family planning assistance, found that the abortion rate in Sub-Saharan Africa rose in countries that had been receiving high levels of U.S. family planning and reproductive health assistance.28 Similarly, another study published in 2011 found that abortion rates in Ghana were higher in rural and poor populations during years when the gag rule was in place than in non–gag rule years.29

The policy threatens the provision of health services in developing countries, increases the risk of unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, and violates medical ethics (see "When Antiabortion Ideology Turns into Foreign Policy: How the Global Gag Rule Erodes Health, Ethics and Democracy," 2017). While the long-term and population-level impacts of President Trump’s global gag rule have not yet been fully realized, stories from around the globe point to growing concerns related to contraceptive access and threats to integrated, comprehensive health programs and strategies.30,31 Ultimately, the global gag rule undermines democratic values and the positive impacts of U.S. global health investments. Congress should reverse and permanently prohibit the global gag rule from being implemented under future antiabortion administrations through legislation such as the bipartisan Global Health Empowerment and Rights (HER) Act, led by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) and Rep. Nita Lowey (D-NY).

Direct U.S. funding back to UNFPA. In the early months of the Trump administration, the State Department issued a determination prohibiting U.S. funding for UNFPA. In justifying its decision, the administration invoked the Kemp-Kasten Amendment, which prohibits U.S. funds from going to any entity that "as determined by the president of the United States, supports or participates in the management of a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization"—something the administration claimed UNFPA was doing by its presence in China. UNFPA states clearly that it opposes "any coercive abortion and the discriminatory practice of prenatal sex selection," and previous U.S. evaluations have found no evidence of UNFPA engaging in either coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization in China or elsewhere.32 In fact, the Trump administration’s justification acknowledged, "there is no evidence that UNFPA directly engages in coercive abortions or involuntary sterilizations in China." Nevertheless, the administration prohibited funding for UNFPA, based on its mere presence in China and its partnership with China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission.

Congress appropriated funding for UNFPA in FY 2018 and is poised to continue to do so in FY 2019. As a result of the Kemp-Kasten determination, however, the funding has been reprogrammed for unspecified family planning, reproductive health and maternal health efforts within USAID. Congress should utilize its oversight role to hold the administration accountable for its inadequate justification and erroneous application of the Kemp-Kasten Amendment and redirect U.S. funding back to UNFPA to support its global reproductive health efforts and its leadership in the face of global humanitarian crises.

Remove coercive requirements and restrictions from PEPFAR. There are three coercive components of the PEPFAR program that Congress can and should repeal. These components prevent the application of evidence-based best practices, limit providers’ ability to meet the needs of patients and clients, and infringe upon the rights of the individuals and communities the program ostensibly seeks to serve. First, at least half of HIV sexual prevention strategy funds under PEPFAR are required to support "activities promoting abstinence, delay of sexual debut, monogamy, fidelity and partner reduction." This requirement runs counter to the preponderance of evidence demonstrating the ineffectiveness of abstinence-only programs at their own goal, as well as potential harms due to stigmatizing and shaming content.33

Second, the refusal clause within PEPFAR allows organizations to deny people access to information and services, including referrals, to which the organization has a religious or moral objection. Numerous faith-based organizations object to key PEPFAR components, such as condom provision, and refuse to refer or partner with organizations for such care.34 As a result, the refusal clause prevents access to lifesaving information, referrals and services, which is a violation of ethical standards of care.

Finally, all recipients of PEPFAR assistance are required to "have a policy explicitly opposing prostitution" and are prohibited from using funds "to promote or advocate the legalization or practice of prostitution or sex trafficking." The anti-prostitution loyalty oath also prohibits the use of funds "to provide assistance to any group or organization that does not have a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking." Although USAID has identified sex workers as a "high-risk population" for HIV infection, organizations have avoided serving this population out of fear of violating the oath.35

Exert oversight to hold the administration to higher standards of U.S. leadership. The Trump administration has engaged in several instances of censorship that weaken U.S. leadership promoting global sexual and reproductive health and rights. The State Department removed the reproductive rights subsection entirely from its Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,36 and political staff within the administration have sought to remove phrases such as "sexual and reproductive health" from annual multilateral agreements, including during United Nations Commission on Population and Development negotiations.37 The administration continues to expand its agenda of censorship, reportedly seeking to bar U.S. staff abroad from using terms like "comprehensive sexuality education" and even "gender."38,39 These and other actions by administration officials opposed to sexual and reproductive health and rights are alarming in their direct impact on U.S. foreign assistance programs and policies, and in how they cede U.S. leadership and leverage for policy change and investments on the global stage.

U.S. leadership around the world is vital in the global effort to meet the health needs and support the rights of all individuals. In particular, U.S. commitment is critical to promoting new and creative solutions to address the unmet health needs of marginalized individuals, families and communities. Congress should wield its full authority to counter the Trump administration’s coercive and ideologically motivated agenda, and demand that the administration uphold the U.S. leadership role and full commitment to advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights around the world.