- Under Bangladesh’s penal code of 1860, induced abortion is illegal except to save a woman’s life.

- Menstrual regulation (MR), however, has been part of Bangladesh’s national family planning program since 1979. MR is a procedure that uses manual vacuum aspiration or a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol to "regulate the menstrual cycle when menstruation is absent for a short duration." MR performed using medication is referred to as MRM.

- Government regulations allow for MR procedures up to 10–12 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period (depending on the type of provider), and MRM is allowed up to nine weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period.

- Despite the availability of MR services, many women resort to clandestine abortions, some of which are unsafe.

- In 2014, some 2.8 million pregnancies— 48% of all pregnancies—were unintended. Abortion and MR procedures accounted for close to three-fifths of unintended pregnancies.*

Incidence of MR and abortion

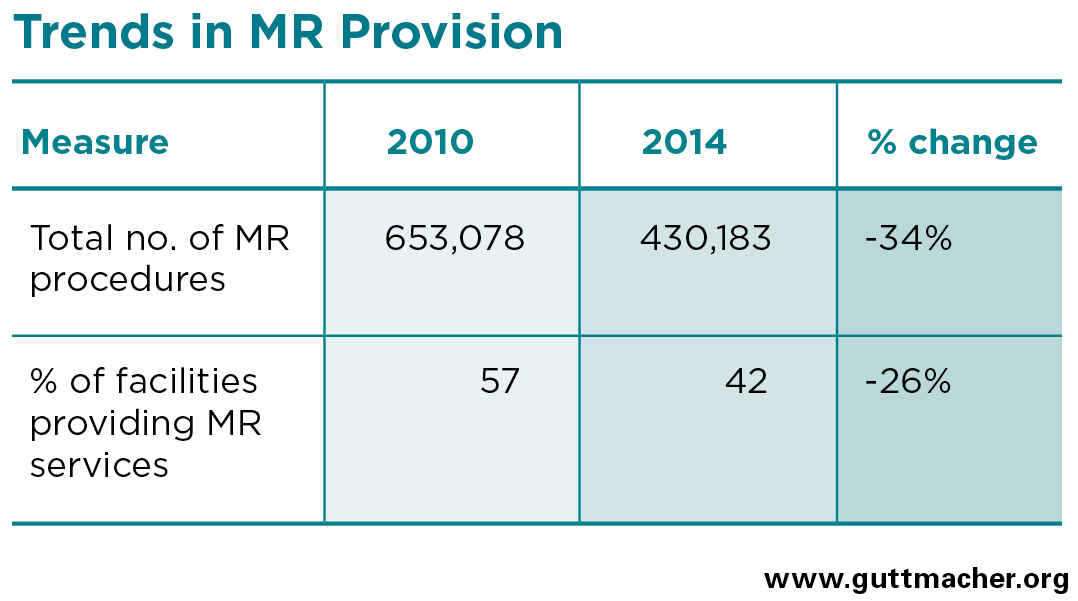

- In 2014, an estimated 430,000 MR procedures were performed in health facilities nationwide, representing a sharp 34% decline since 2010.

- In addition, an estimated 1,194,000 induced abortions were performed in Bangladesh in 2014, and many of these were likely done in unsafe conditions or by untrained providers.

- The annual rate of MR in 2014 was 10 per 1,000 women aged 15–49, down from 17 in 2010.

- The annual abortion rate in 2014 was 29 per 1,000 women aged 15–49. Because of changes to the methodology for estimating abortion incidence, this rate is not comparable to the rate estimated for 2010. The rate was highest in Khulna (39) and lowest in Chittagong (18).

Provision of and trends in MR services

- Nationally, only 53% of public-sector facilities permitted to provide MR services actually did so in 2014 (down from 66% in 2010). At 20%, this proportion was much lower among private-sector facilities (down from 36% in 2010).

- Only about half of all union health and family welfare centres (UH&FWCs) capable of providing MR procedures did so in 2014, a significant decline from two-thirds in 2010. These facilities are the primary health providers in rural areas, where the majority of the population lives.

- The number of MRs provided by UH&FWCs also dropped precipitously, from 302,000 in 2010 (close to half of all MR procedures in the country) to 138,000 in 2014. The decline in procedures at UH&FWCs accounted for close to three-quarters of the total nationwide decline.

- The decline in the proportion of UH&FWCs providing MR services may have been due, in part, to a lack of training among a recently recruited cohort of providers who were recruited to replace a large cohort of providers reaching retirement age. At UH&FWCs that did not offer MR services in 2014, 92% of providers aged 20–29 said they did not provide MR because they lacked training in the procedure.

- In 2014, 57% of MR procedures were performed in public facilities, down from 63% in 2010. NGOs provided 35%, and private clinics provided 8%, of MR services.

- Facilities reported that almost all MR patients received contraceptive counseling (99%), but much smaller proportions were given a contraceptive method: 77% of those receiving MRs at public facilities and only 7% of those attending private facilities.

Treatment for complications of unsafe abortion

- An estimated 384,000 women suffered complications from clandestine abortion in 2014. One-third of those requiring facility-based treatment did not receive the postabortion care (PAC) they needed.

- In 2014, 91% of public and private health facilities considered able to provide PAC did so, an increase from 84% in 2010. The most common complications treated were hemorrhage and incomplete abortion; more serious complications, such as shock, sepsis and uterine perforation, were also reported.

- Between 2010 and 2014, there was a marked increase in the proportion of PAC patients diagnosed with hemorrhage, from 27% to 48%.† It is possible that this rise is related to an increase in the incorrect clandestine use of misoprostol.

- Poor women and rural women are the groups considered most likely to be at risk for complications from unsafe abortion. Respondents to the 2014 Health Professionals Survey estimated 85% of nonpoor urban women in need of facility-based care for complications from clandestine abortion would receive it, compared with only 47% among their poor rural counterparts.

- Nearly all public and private facilities that provided PAC in 2014 (99%) offered family planning counseling to the vast majority of their PAC patients. However, only 18% of these facilities provided their patients with contraceptive methods.

Barriers to MR services

- Even though the MR program has been supported by the government of Bangladesh since 1979, many women are unaware of its services. National Demographic and Health surveys show that, in 2014, more than half of ever-married women in Bangladesh had never heard of MR, a marked increase from only one-fifth of married women in 2007.

- On average, among facilities in the public and private sector that could potentially provide MR services, three in 10 lacked basic MR equipment, trained staff or both in 2014. In addition, many facilities that had trained staff and the equipment to provide MR procedures did not do so. This was especially common in the private sector: Although 63% of private facilities reported having both the equipment and trained staff, only about one-third of these facilities actually provided MR.

- Public and private facilities reported refusing to provide MR services to an estimated 105,000 women in 2014. This figure represents about one-quarter (27%) of all women seeking MR at these facility types.

- Most facilities reported having turned away women seeking MR because they had exceeded the permitted number of weeks after their last menstrual period or because of medical reasons. However, some providers also cited social or cultural reasons not reflective of government guidelines: 27% reported turning away women because they were childless, 6% because women were unmarried, 7% because they considered the woman too young and 8% because the woman’s husband had not consented.

Recommendations

- Increase the training of providers in the provision of MR and MRM, with a particular focus on UH&FWCs.

- Ensure facilities have the necessary equipment, medication and trained staff to provide MR.

- Increase providers’ awareness of the national MR guidelines, including information on the appropriate reasons for refusing to provide MR.

- Educate women about MR services. Ensure they know about this free, legal alternative to illegal abortion; where to obtain services; and the window of time since their last menstrual period during which MR is permitted.

- To reduce complications associated with the use of misoprostol and mifepristone, increase awareness among drug sellers and their clients of the correct use and dosage of these drugs through informational leaflets or posters and clear, accurate drug labeling.

- To reduce high rates of unintended pregnancy, increase the provision of high-quality contraceptive care by providing a wide range of methods (including long-acting reversible methods), offering counseling on consistent and correct use, and facilitating method switching.