In 2002, Pakistani women experienced about 2.4 million unintended pregnancies;* nearly 900,000 of these pregnancies were terminated by induced abortion.1 Because abortion is legal only in very limited circumstances, women who seek it subject themselves to clandestine and often unsafe procedures. Poor women, in particular, are forced by circumstances to rely on untrained providers.

Abortion in Pakistan

Reproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

The deaths, serious health complications and long-term disabilities that result from unsafe procedures place an enormous burden on the nation’s health care system, as well as on the women themselves, their families and their communities. A national survey of public-sector facilities estimated that about 200,000 women were hospitalized for abortion complications in 2002.1 In addition, many other women suffered complications but never reached hospitals.

Current law permits abortion only to save the woman’s life or, early in pregnancy, to provide "necessary treatment" (see box). Because almost all abortions take place illegally and in secret, information about abortion in Pakistan comes largely from studies of women hospitalized for abortion complications. While the evidence is limited, it is clear that postabortion complications account for a substantial proportion of maternal deaths in Pakistan.

How widespread is abortion in Pakistan?

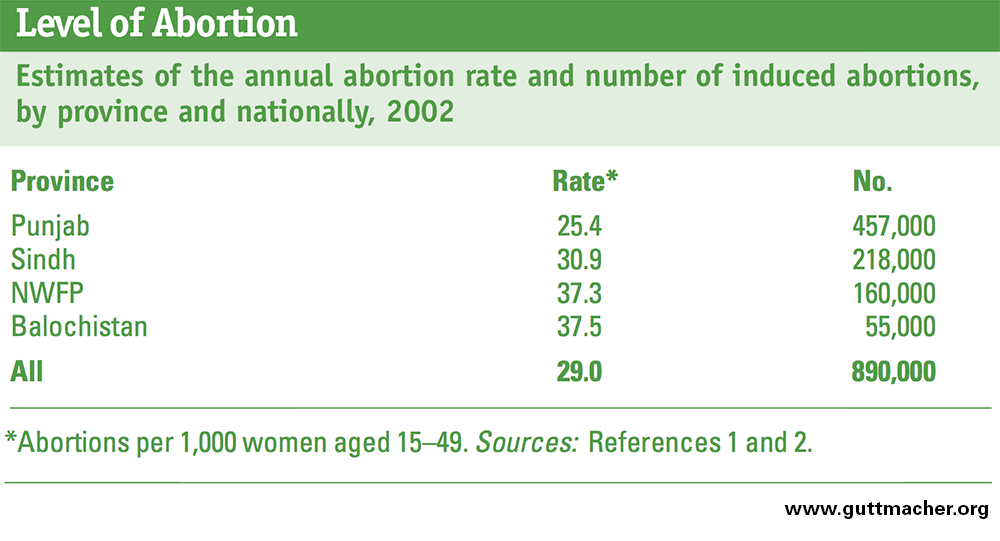

A nationwide study estimated that 890,000 induced abortions took place in 2002.1,2 This amounts to 29 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age. Of every 100 pregnancies, 14 ended in induced abortion.

Abortion rates appear to be substantially higher in the two more rural of Pakistan’s four provinces. In North West Frontier Province, an estimated 37 abortions took place per 1,000 women aged 15–49 and in Balochistan the rate was 38 per 1,000. By comparison, rates were lower in the two more urban provinces: 25 in Punjab and 31 in Sindh, where contraceptive use is also somewhat higher.1

Because it is almost impossible to obtain reliable data on induced abortion through direct interviews with women, these rate estimates derive from an established indirect method that uses health facility data on women treated for postabortion complications and experts’ estimates of the likelihood of hospitalization after abortion. Given the stigma and illegality of abortion in Pakistan, women themselves are very reluctant to admit to having had induced abortions. For example, at a Karachi teaching hospital in 1997–1998, only 7% of the women presenting with postabortion complications acknowledged that their abortions had been induced.3

Some small-scale community-based studies provide measures of the prevalence of induced abortion and also support the conclusion from the national study that the level of abortion is moderately high in Pakistan. A study in an urban slum in Lahore in 1992–1993 found that 16% of a random sample of women reported having had at least one induced abortion.4 More recently, a qualitative 2006 study of a village in Rawalpindi district found that 20% of pregnancies resulted in abortions or "attempted abortions."5

The latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in Pakistan, conducted in 2006–2007, found that 24% of births were unplanned.6 While the level of induced abortion may not be known with precision, it is clear that the procedure is common in all regions, despite its illegality, and that it is a response to the high level of unintended pregnancy.

Who are the women having abortions?

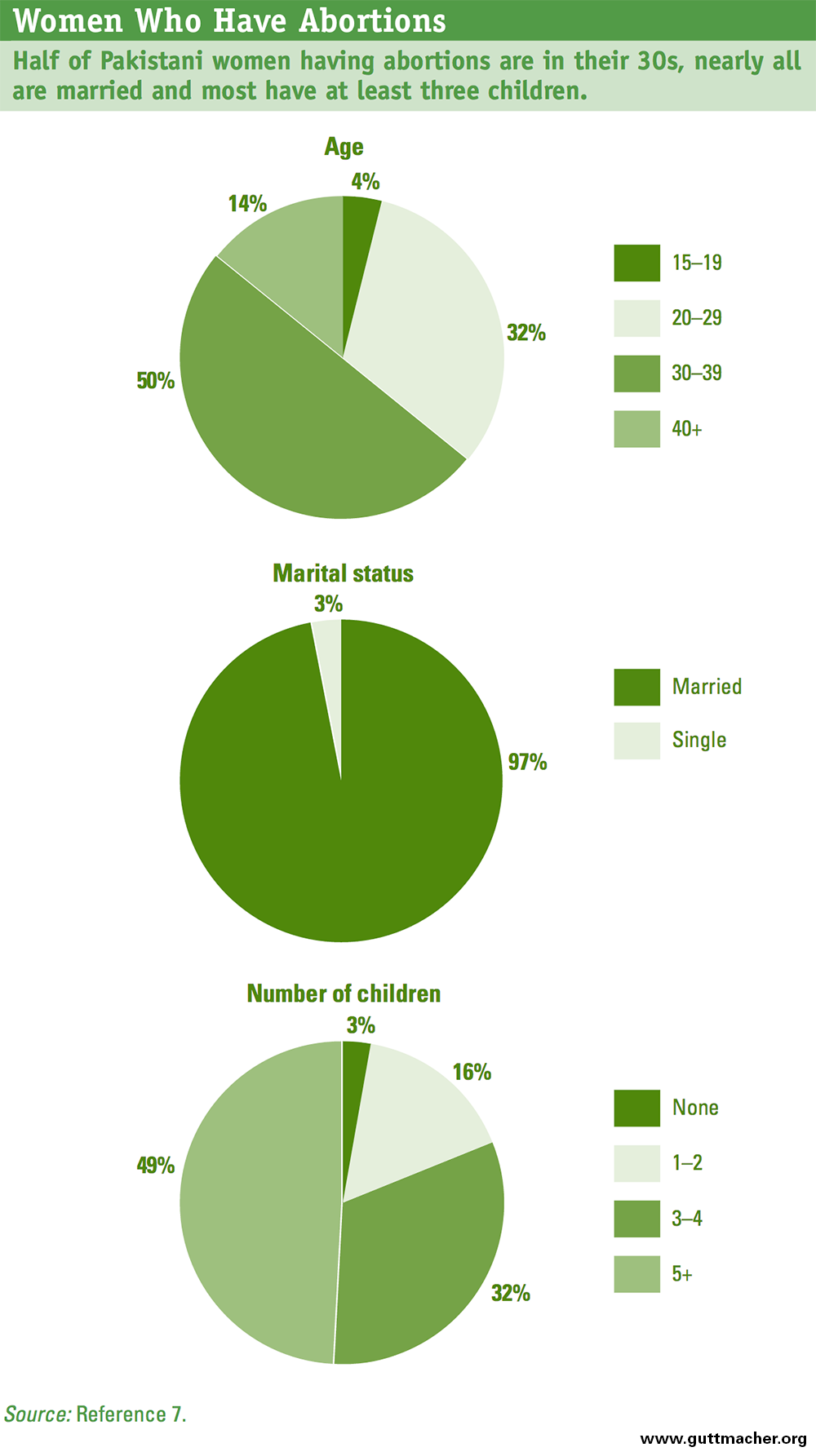

If the women hospitalized for abortion complications are typical, most women who have induced abortions in Pakistan are married and already have more children than the average Pakistani woman wants (Figure 1).7 In one study, 70% of women were aged 25–39;7 in another study, 78% were aged 25–34.8 The average age of the women reported in several studies was just under 30.9–11 Moreover, almost all the women were married.11,12 This pattern is typical of many Asian countries: Most abortions occur among currently married, older women and not among unmarried adolescent women, as is more typical in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

The number of living children that women already have when they decide to abort is quite high, and since Pakistani women want an average of 3.1 children,6 the women who seek abortions most likely have already had more children than they wanted. Some studies of postabortion care patients have found that the average is around four children.9–11 Other studies show that about 50% or more of women hospitalized for postabortion complications had five or more living children.7,8,12

With regard to other possible contributing factors, evidence to date does not indicate that either women’s education or their contraceptive-use behavior influences whether or not they resort to induced abortion. In fact, some studies show that the educational profile of women who have induced abortions is similar to that of the female population in general.11,13

The legal status of abortion in Pakistan

In 1990, the Pakistan government revised the colonial-era Penal Code of 1860 with respect to abortion. The revisions sought to conform better to Islamic teachings regarding offenses against the human body. Under the 1990 revision, the conditions for legal abortion depend on the developmental stage of the fetus—that is, whether the fetus’s organs are formed or not. Islamic scholars have usually considered the fetus’s organs to be formed by the fourth month of gestation. Before formation of the organs, abortions are permitted to save the woman’s life or in order to provide "necessary treatment." After organs are formed, abortions are permitted only to save the woman’s life.

Likewise, the penalties for illegal abortion depend on the fetus’s developmental stage at the time of the abortion. Before organs are formed, the offense is penalized under civil law (ta’zir), by imprisonment for 3–10 years. After organs are formed, traditional Islamic penalties, in the form of compensation (diyat), are imposed. Depending on the outcome of the abortion, imprisonment may be imposed as well.

Source: United Nations Population Division, Abortion Policies: A Global Review, New York: United Nations, 2002.

What are the consequences of unsafe abortion?

Unsafe abortion in Pakistan contributes significantly to avoidable illness and death. Studies document that when women who have had unsafe abortions do reach health facilities, they commonly suffer from a range of postabortion complications—incomplete abortion, hemorrhage or excessive bleeding, trauma to the reproductive tract or adjacent anatomical areas, sepsis (bacterial infection) and a combination of these complications.3,8–11,13–16 Excessive bleeding may have life-threatening consequences, such as anemia or shock. Perforations and lacerations may occur to the vagina, cervix or uterus and may involve injury to adjacent areas, such as the bowel, requiring surgery with full anesthesia. Hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) may be required, leaving the woman permanently infertile. If not treated in time, sepsis can lead to peritonitis (inflammation of the abdominal lining), septicemia (blood poisoning), kidney failure and septic shock, all of which can be life-threatening.

In 2002, an estimated 197,000 women were hospitalized for complications of unsafe abortion.1 This amounts to 6.4 hospitalizations per 1,000 women aged 15–49. High as this figure is, it likely represents only a portion of the actual number of women experiencing complications. For instance, Pakistani experts estimate that only around half of poor women who need treatment for severe complications of abortion reach hospital-based care.12 More affluent women are considered to be more likely to obtain care for abortion complications—about four in five who need hospital-based care receive it. In addition, women who are poor and live in rural areas are considered to be least likely to obtain care when they have complications.1,2

A few small-scale facility-based studies have given us a partial, incomplete picture of the true extent of the tragedy of death resulting from an unsafe abortion. They show that even when women do reach hospitals, perhaps one in 10 die. During a 21-month period in 1997–1998, for example, 10% of women admitted to a large teaching hospital in Karachi for postabortion care died of complications.3 Septicemia was the most common cause of death.

Unsafe abortion is also the cause of a substantial proportion of maternal deaths occurring in hospitals. A 1999–2001 university hospital study found that 11% of all maternal deaths that occurred in the hospital during this period were caused by complications resulting from unsafe abortion.14 In an earlier hospital study (1992–1994), unsafe abortion caused 15% of maternal deaths.8

These studies likely reveal only the tip of the iceberg. Little is known of the fate of the women who need treatment but do not receive it. In addition, other important consequences of unsafe abortion have not been studied in Pakistan—in particular, long-term disabilities, infertility and the economic costs to individuals, families, the health care system and society.

Who performs abortions, and how are they done?

Both formally trained health personnel and traditional practitioners perform abortions in Pakistan, often under unsafe conditions. Who performs the abortion and how safe it is often depend on where a woman lives and how much she can afford to pay for the procedure.

Poor rural women are much more likely to obtain abortions from untrained providers than are nonpoor urban women. As part of the 2002 national study, more than 100 knowledgeable health professionals, drawn from all four provinces, considered how women’s economic status and residence influence access to formally trained abortion providers.2 They estimated that, on average, only 7% of poor rural women obtained their abortions from doctors, while 42% went to dais (traditional birth attendants). By comparison, an estimated 49% of nonpoor urban women had doctors perform their abortions, while only 9% went to dais. Among poor women who lived in urban areas, an estimated 34% went to dais.

According to the 2002 survey of health professionals, the price of an abortion varies greatly, depending on the type of provider and the woman’s ability to pay.12 For example, poor rural women pay an estimated US$21 for an abortion provided by a nurse-midwife, nonpoor rural women and poor urban women pay US$30 and nonpoor urban women pay US$48. Poor rural and poor urban women who go to dais or other lay practitioners pay the equivalent of US$8–17. These prices highlight the inequity in Pakistani women’s access to safe abortion: More affluent women can afford expensive, safer abortion procedures, while poor women must make do with untrained personnel whose care is less expensive but often riskier and more harmful.

Going to a trained health care provider for an abortion is no guarantee of safety, however. Many women who experience complications have had abortions performed by doctors or nurses. At a large teaching hospital in Karachi in 1997–1998, 30% of women receiving care for abortion complications told researchers that a doctor had performed their abortions, and 36% said a nurse or lady health visitor had done the procedure.3 Dais had performed the abortion for 32% of the women. Only 2% had a self-induced abortion. In urban squatter settlements in Karachi, women listed private hospitals, clinics and dais’ homes as the most common places to obtain abortions.16

Abortions can be obtained in clandestine clinics, at least in large urban areas and provided one can afford the cost—but again, they are not always safe.13 Of 32 clinics studied in 1997 in three provincial capitals, 10 clinics were run by female doctors, 13 by lady health visitors, six by other types of nurses and three by paramedics. Although most clinics employed trained personnel, only seven were properly equipped to carry out abortions safely. Providers typically performed dilatation and curettage procedures. They almost never used manual vacuum aspiration, a less invasive procedure.

Abortions seem to take place at a fairly early gestational age. Among women receiving postabortion care at a large teaching hospital in Karachi, 43% of the abortions had taken place in the first eight weeks of gestation and another 39% took place between the ninth and 14th weeks.3 Nonetheless, 18% occurred at 15 weeks or later, when the probability of severe complications is elevated. The study of clandestine abortion clinics found that abortions at such clinics took place at an even earlier gestational age, on average.13

In general, what we know about how abortions take place in Pakistan is limited to information obtained through facility-based investigations. Since women who either have no negative health consequences or who endure illnesses without treatment are not reached through facility-based studies and are very unlikely to have reported their abortion experiences in the few existing community-based studies, the patterns of abortion procurement described here may well present an incomplete picture.

Why do women have abortions?

Given the health risks, the illegality and the stigma, why do so many women have abortions? While unintended pregnancy is the primary reason women seek abortions, studies have probed the underlying reasons for the unwantedness of those pregnancies. Poverty and having had all the children they want are the two most common factors cited by women as their reason for deciding to terminate a pregnancy.7,10,13 In a 2002 study in three of Pakistan’s four provinces, 54% of women who had had abortions said that they could not afford to have another child,7 and 55% said that they had "had enough children"; 25% said that it was "too soon" to have had another child (women could give more than one reason). Similarly, in low-income areas of Karachi, "too many children," "poverty" and "unemployed spouse" were the most common reasons why women sought abortions.15, 16

In 1997, clients at clandestine abortion clinics in three provincial capitals reported a somewhat different mix of reasons for abortion.13 While 64% said their primary reason was "too many children," which is consistent with both of the major reasons mentioned above, other reasons were also cited. For example, 20% said their contraceptive method had failed; nearly all of these women—96%—had been using traditional methods. Some 5% cited "medical reasons" as the primary rationale for their abortions. "Premarital affairs" were mentioned by 9% of women, and "extra-marital affairs" by 1%, confirming that in Pakistan relatively few pregnancies occur outside marriage.

These findings suggest that many married women and their husbands have difficulties obtaining contraception or using it effectively, and that abortion is oten used as a back-up when unintended pregnancies occur. The predominantly economic reasons for abortion speak to the burden that adding another child to the household can place on some Pakistani families. This same rationale could motivate wider contraceptive use if effective family planning methods were more available and their use were more acceptable.

How does contraceptive use relate to unintended pregnancy and abortion?

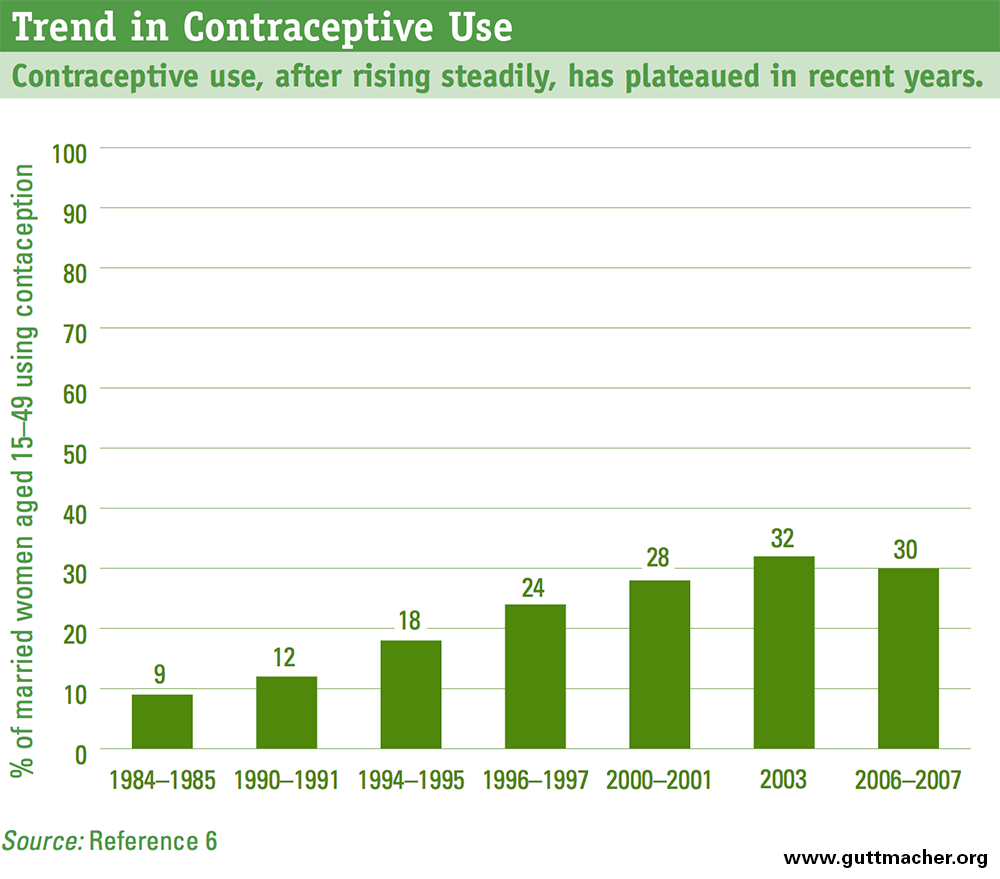

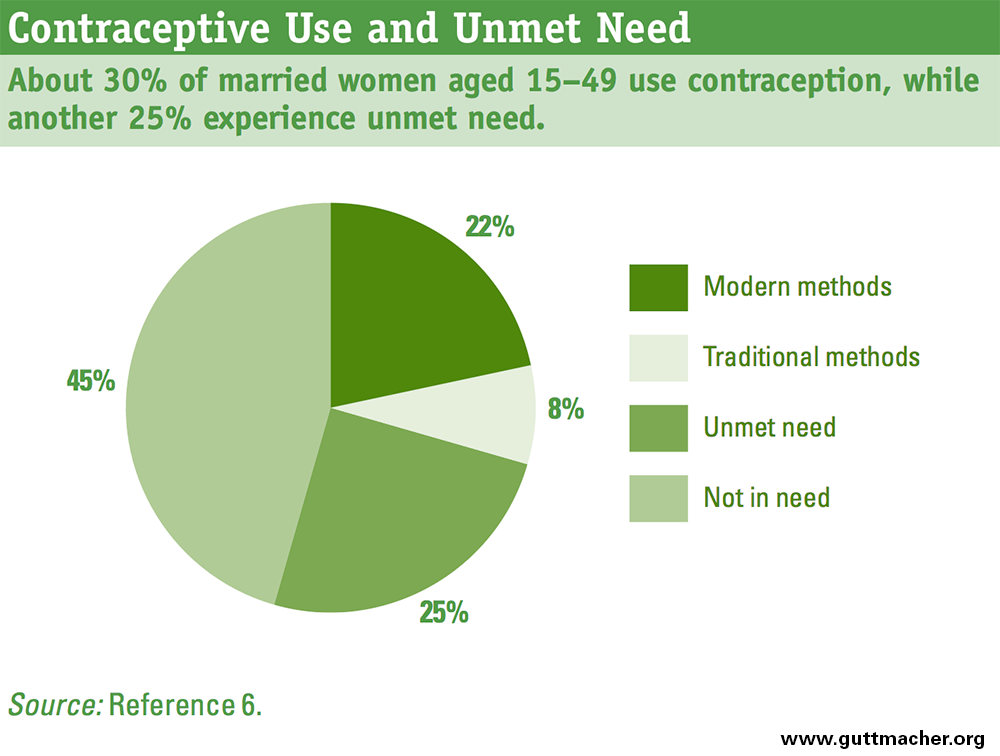

While contraceptive use increased gradually in Pakistan until 2003, it has changed relatively little since then (Figure 2).6 Nationally, only about 30% of married women of reproductive age currently use a contraceptive method, according to the 2006–2007 DHS survey. Moreover, more than one-quarter of contraceptive users rely on traditional, low-efficacy methods such as withdrawal or periodic abstinence, leaving themselves largely unprotected against unwanted pregnancy. The survey asked women who were not currently using a method about their intention to use one in the future. Encouragingly, half said that they intended to use contraception in the future; it is not known why these women were not using a method at the time. Most of the rest said they did not intend to use in the future, and a small proportion were unsure what they would do. Women who did not intend to use contraception in the future were asked why. Among the key reasons were fatalism (for example, "it’s up to God"), cited by 28%; a perception that they are not at risk of pregnancy (25%); and opposition by the respondent, her husband or others (23%). About 15% of the group gave reasons related to side effects or lack of knowledge about contraception.

Compared with the cross-section of Pakistani women in the DHS survey who were not using contraception and did not intend to do so in the future, a higher proportion of clients interviewed at clandestine abortion clinics in 2002 expressed concerns about the safety of contraceptive methods (46%).13 To a very great extent, however, among women having abortions, most of those who report that they experienced contraceptive failure were using methods with relatively low levels of effectiveness (condoms, withdrawal and rhythm).

While Pakistan's fertility rate is high compared with more developed countries, it is lower than would be predicted by the country's low level of contraceptive use: On average, women have 4.1 live births, and, in metropolitan areas, the rate is just 3.0 live births. It is difficult to explain such fertility rates solely in terms of contraceptive use. Widespread induced abortion is likely to an important contributing factor. The fact that women in the two less developed provinces—Balochistan and North West Frontier Province—have lower contraceptive use rates and higher abortion rates than women in the more developed provinces supports this interpretation.1

There appears to be a great need to increase and improve contraceptive use in Pakistan. One-quarter of currently married women —an estimated 7.4 million women in 2006–2007—have an unmet need for contraception (Figure 3).6 In other words, they either do not want any more children or do not want a child at the present time, but they are not using contraception. Moreover, there continues to be a significant gap in women’s ability to have the family size they want—women report that they want three children, even though on average they are having four.

Conclusions

The combination of a relatively high national level of fertility with a relatively low level of contraceptive use and a moderately high rate of abortion suggests that many Pakistani women are using abortion as part of their strategy to avoid unwanted or mistimed births, notwithstanding the illegality of the procedure and the considerable health risks it entails, as evidenced by the large number hospitalized for treatment of complications each year. The need to seek recourse to abortion is likely to be especially prevalent among women who fear that contraceptives will damage their health, who believe that their husbands object to family planning, or who feel that religious and social norms do not endorse contraceptive use. In addition, many women may have difficulty obtaining the modern methods they need. Under current circumstances, many Pakistani women are paying with their health—and even their lives—to avoid births that they cannot afford or do not want. Helping them avert unintended pregnancy and supporting them in achieving their fertility goals would significantly reduce maternal morbidity and mortality and the associated costs to families, communities and society as a whole.

References

1. Sathar ZA, Singh S and Fikree FF, Estimating the incidence of abortion in Pakistan, Studies in Family Planning, 2007, 38(1):11–12.

2. Population Council, Unwanted Pregnancy and Post-Abortion Complications in Pakistan: Findings From a National Study, Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council, 2004.

3. Bhutta S, Aziz S and Korejo R, Surgical complications following unsafe abortion, Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 2003, 53(7):286–289.

4. Maternity and Child Welfare Association of Pakistan (MCWAP), Reproductive Morbidity in an Urban Community of Lahore, Karachi, Pakistan: MCWAP, no date.

5. Arif S and Kamran I, Exploring the Choices of Contraception and Abortion among Married Couples in Tret, Rural Punjab, Pakistan, Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council, 2007.

6. National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) and Macro International, Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006–07, Islamabad, Pakistan: NIPS, 2008.

7. Casterline J and Arif S, Dealing with unwanted pregnancies: insights from interviews with women, Research Report, Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council, 2003, No. 19.

8. Tayyab S and Samad N, Illegally induced abortions: a study of 37 cases, Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 1996, 6(2):104–106.

9. Jamil S and Fikree FF, Incomplete Abortion from Tertiary Hospitals of Karachi, Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan: Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, no date.

10. Korejo R, Noorani K and Bhutta S, Sociocultural determinants of induced abortion, Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 2003, 13(5):260–262.

11. Siddique S and Hafeez M, Demographic and clinical profile of patients with complicated unsafe abortion, Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 2007, 17(4):203–206.

12. Rashida G et al., Abortion and Post-Abortion Complications in Pakistan: Report from Health Care Professionals and Health Facilities, Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council, 2003.

13. Rehan N, Inayatullah A and Chaudhary I, Characteristics of Pakistani women seeking abortion and a profile of abortion clinics, Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 2001, 10(8):805–810.

14. Mahmud G and Mushtaq Z, The Incidence and Outcome of Induced Abortions at One of the Hospitals of Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Association of Pakistan, 2001.

15. Saleem S and Fikree FF, Induced abortions in low socio-economic settlements of Karachi, Pakistan: rates and women's perspectives, Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 2001, 51(8):275–279.

16. Jamil S and Fikree FF, Determinants of Unsafe Abortion in Three Squatter Settlements of Karachi, Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan: Department of Community Health Sciences, Aga Khan University, 1998.

FOOTNOTES

*Numbers are based on calculations using data presented in reference 1.

Acknowledgments

This In Brief was written by Michael Vlassoff, Susheela Singh and Gustavo Suarez, all of the Guttmacher Institute, and Sadiqua N. Jafarey of the National Committee for Maternal and Neonatal Health (NCMNH), Pakistan. It was edited by Ward Rinehart, independent consultant, and Haley Ball, Guttmacher Institute.

The authors thank Zeba Sathar and Ali Mohammad Mir, both of the Population Council, Pakistan, and Imtiaz Kamal, Azra Ahsan, Nighat S. Khan, all of the National Committee for Maternal and Neonatal Health, for their comments on earlier drafts of the report. They also thank the following Guttmacher colleagues: Patricia Donovan for input on drafts, and Alison Gemmill and Liz Carlin for research assistance.

The 2002 national study on which many of the report’s findings are based was supported by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to the Population Council, Pakistan.

Suggested citation: Vlassoff M et al., Abortion in Pakistan, In Brief, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2009, No. TK