Corrected April 2, 2024. See notes below.

Medication abortion has become critical for abortion care. Despite being the most commonly used method of abortion in the United States, there is still substantial misunderstanding about what constitutes a medication abortion and how to obtain one, either within or outside of the formal health care system.

Now that the US Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade, targeting medication abortion use has become a central strategy of anti-abortion advocates and policymakers. From state capitals to Congress to the courtroom, abortion opponents use misinformation about medication abortion in their efforts to eliminate access to all abortion. It is imperative to counter misinformation and junk science with facts and reliable research. Central to that goal is using accurate, consistent and nuanced language when discussing medication abortion and related terminology.

In this explainer, we describe medication abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol, explain the ways that people in the United States access those pills, describe self-managed medication abortion, and provide research and policy context for these concepts.

Medication Abortion

Medication abortion, also known as “abortion pills” or “medical abortion,” is a safe and effective way to terminate a pregnancy. Medication abortion is the most common method of abortion in high-income countries, and the method has become increasingly common in the United States since mifepristone was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000. According to Guttmacher data, medication abortion accounted for more than half of all abortions in the United States in 2020, and its share of all abortions has likely increased in the past several years.

There are various drug regimens shown to be effective at ending a pregnancy. The most common regimen offered by US providers involves two drugs used in combination: mifepristone, which stops the pregnancy from continuing, and misoprostol, which causes uterine cramping and expels the pregnancy. While the FDA approved this two-drug regimen for up to 70 days (10 weeks) of pregnancy, emerging data show that medication abortion is also safe and effective beyond 10 weeks of pregnancy. Using misoprostol alone to end a pregnancy is also a well-used and safe regimen, supported by leading professional and medical organizations in the United States and around the world.

Within the formal US health care system, there are multiple ways that a person can obtain mifepristone and misoprostol. These include an in-person visit with a health care provider, where the mifepristone can be taken on-site or at home, and then the misoprostol is taken at home 24–48 hours later. In some states, abortion pills can be provided from a certified pharmacy—in person or via mail—after being prescribed by a health care provider consulted via phone, video, text or an online platform.

Some people source abortion pills through community networks, websites that sell pills or other means without interacting directly with a health care provider. This is a form of self-managed medication abortion, discussed in further detail below.

FDA restrictions

Unlike almost any other area of health care, abortion provision has been heavily scrutinized and over-regulated, despite clear evidence of its safety. In that context, when the FDA originally approved mifepristone for use in the United States in 2000, it restricted how the drug could be prescribed and dispensed. For example, while most prescription medications can be obtained at a pharmacy, the FDA required clinicians to distribute mifepristone in person, which generally required them to keep the medication in stock in their clinic, doctor’s office or hospital. Given the robust evidence of safety already known at the time and included with the FDA application, these were medically unnecessary restrictions that created burdens and prevented many providers from offering the care.

Over time, the body of medical evidence from the United States and globally about the safety and use of mifepristone has continued to grow. The FDA recently responded by loosening some restrictions, most prominently by lifting the in-person dispensing requirement.

Expanded access with telemedicine

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telemedicine for all types of health care increased dramatically. Policymakers and insurance providers responded to the need for fewer in-person interactions by covering a variety of remote consultation visits, at least for the duration of the public health emergency. In that context, the FDA temporarily suspended the 2000 in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone, allowing people to obtain medication abortion by telemedicine. Patients were able to have a clinical consultation by phone, text, video or online platform, and then have abortion pills mailed to their home by the provider or a certified online pharmacy.

Since 2020, a new type of abortion provider has entered the scene: online-only clinics (also referred to as telemedicine-only clinics) that offer medication abortion services without a physical location. There has been a steady increase in their number from zero in 2020 to 32 (4% of all medication abortion providers) in 2021 and 69 (9%) in 2022. These online clinics have come to play an important role in abortion access, accounting for more than 8% of all abortions provided by clinicians nationwide in the first 12 months after the 2022 Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision that overturned Roe.

The number of physical facilities and online-only providers in the United States using telemedicine and mailing abortion pills increased from 52 (7% of all facilities offering medication abortion) in 2020, to 91 (12%) in 2021 and to 243 (31%) in 2022. As the public health emergency was ending, the FDA undertook a full review of the mifepristone restrictions and, given clear evidence of safety and effectiveness, permanently suspended the in-person dispensing requirement in January 2023.

State restrictions

Over the last two decades, anti-abortion policymakers have been actively working to restrict abortion by any and all means, including by restricting access to medication abortion. The fall of Roe in 2022 has accelerated these efforts.

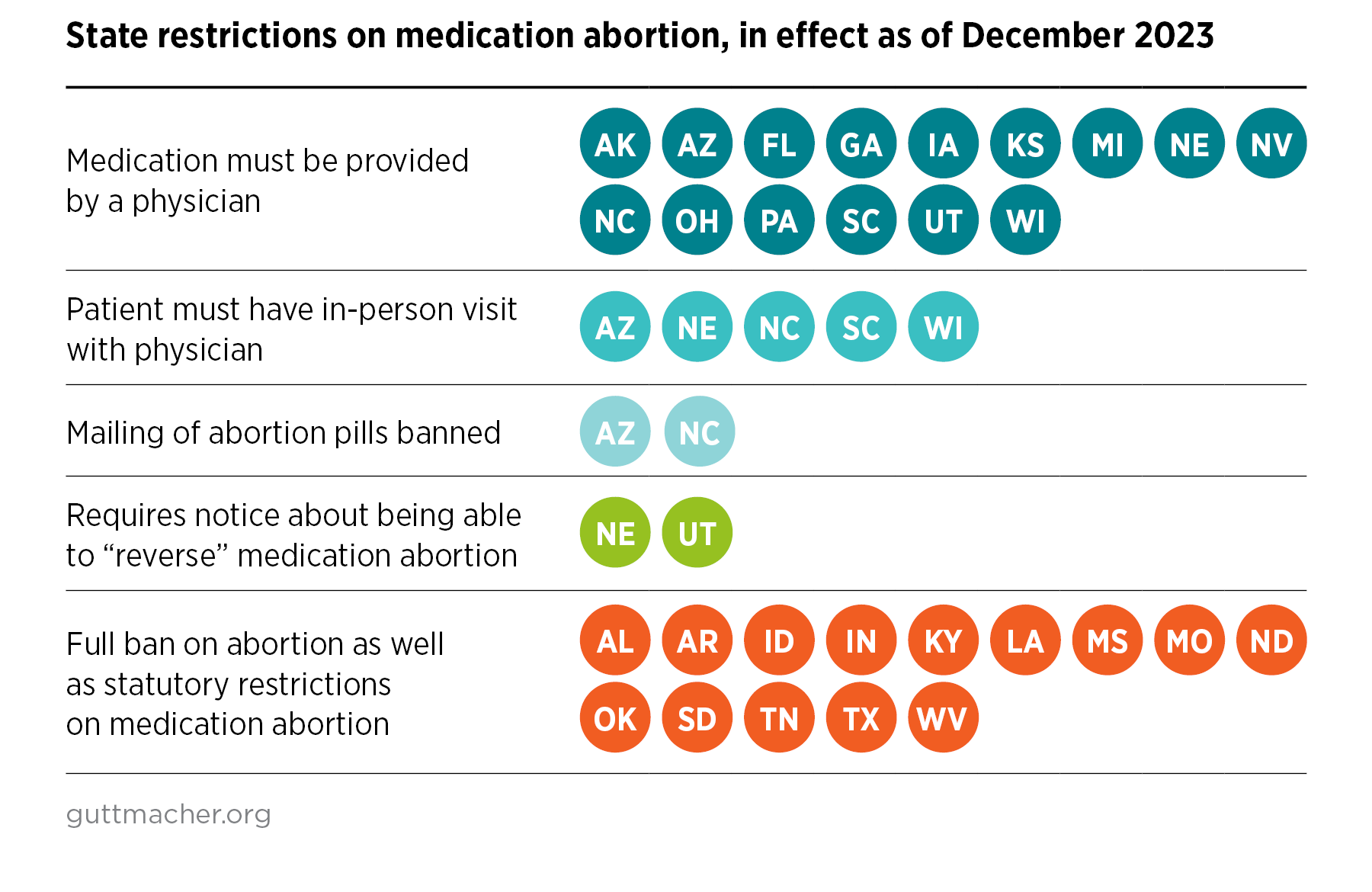

Today, over half of all US states (29) have laws mandating medically unnecessary barriers that restrict access to medication abortion. In 14 of these states, abortion is banned almost completely, superseding state laws imposing specific restrictions on medication abortion. In the other 15 states, statutory restrictions on medication abortion tend to focus on limiting who can prescribe medication abortion pills or how pills can be provided. All 15 states require medication abortion to be provided by a physician, despite evidence by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other medical groups that advanced practice clinicians can safely provide medication abortion. In addition to restrictions on access, two states where abortion remains legal have laws that require medical personnel to give medically inaccurate information to people seeking abortion, such as about how to “reverse” a medication abortion.

Several states where abortion is not entirely banned specifically target the use of telemedicine for medication abortion: Arizona, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina and Wisconsin require that a patient being prescribed medication abortion have an in-person visit with a physician, and Arizona and North Carolina also ban mailing medication abortion pills to a patient. These requirements do not improve health outcomes. They only serve to make inefficient use of health care resources and clinicians’ time, while denying patients quality care that comes with added convenience and flexible scheduling.

Federal protections and potential restrictions

As a counter to these state efforts, federal policy supports the right to travel across state lines for health care and allows medications, including mifepristone, to be sent in the mail. In December 2022, the US Department of Justice issued an opinion reinforcing that it is legal to send medication abortion in the mail.

In Congress, anti-abortion lawmakers have introduced federal legislation that attempts to supersede the authority of the FDA. In addition to a bill that would outright ban medication abortion, another bill would prohibit the FDA from considering future applications for “abortion drugs” and others would dictate onerous and medically unnecessary prescribing protocols. Similar to state policies restricting access to medication abortion, some of the federal bills proposed would restrict the use of telemedicine for provision of medication abortion. There are also attempts to insert restrictions on medication abortion into larger, must-pass funding bills, including legislation to fund the US Department of Agriculture, the FDA and other agencies.

Court challenges

Several cases involving medication abortion are being litigated in court. Most prominently, Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA challenged the FDA’s approval of mifepristone, seeking to have it withdrawn from use, and failing that, attempting to force the agency to reinstate the outdated and unnecessary restrictions that originally constrained its use. The plaintiffs relied on low-quality science and misinformation about the safety and effectiveness of medication abortion to make their case, attempting to capitalize on confusion and misunderstanding to restrict access to abortion.

The case was heard by a federal court in Texas and then appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, well-known to be hostile to abortion rights. A three-judge panel of the appeals court issued a ruling in August 2023 that left in place the FDA’s approval of mifepristone in 2000, but would reinstate some of the burdensome regulations, such as the requirement for in-person dispensing. The US Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in March 2024 and mifepristone remains available under the current regulations in the meantime. This case has the potential to impose severe restrictions on mifepristone (although the misoprostol-only regimen would be unaffected).

Self-managed Medication Abortion

In the context of use in the United States, self-managed abortion refers to abortions that take place outside the formal health care system. People have been self-managing abortions for centuries via a variety of methods, including herbs and medicines. They do so for any number of reasons, including a preference for the privacy and convenience of managing the care at home, or a lack of funds or access to care from a health care facility nearby. In recent decades, there has been an increase in people in the United States using medication abortion—either mifepristone and misoprostol or misoprostol alone—to safely and effectively self-manage their abortions.

In 2022, WHO updated its guidance that recommends the option of self-management of medication abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy (this applies to the combination regimen of mifepristone plus misoprostol, and the use of misoprostol alone). WHO identified three components of a high-quality process—self-assessment of eligibility, self-administration of abortion medicines and self-assessment of the abortion’s success—and concluded that individuals can safely and effectively manage each of those components.

There are no comprehensive data on the incidence of self-managed medication abortion in the United States. The limited findings that exist show it has been increasing in the past several years, particularly in response to reduced clinic access during the COVID-19 pandemic and the proliferation of abortion restrictions that create barriers to access. Part of this increase is likely due to the expanded accessibility of medication abortion drugs, either from online providers or via local community networks. An analysis from an online telemedicine service revealed an increase in requests for self-managed abortion following the Dobbs decision in June 2022, with the largest increases in requests from people in states that implemented total abortion bans; increases were also observed in states where the legal status of abortion did not immediately change. Other research, using data from thousands of individuals and conducted by groups that facilitate self-managed medication abortion, has documented that it is a safe and highly effective method for terminating a pregnancy.

Options for self-management

Since Roe was overturned, self-managed medication abortion has become a lifeline for many in the United States who cannot access care through the formal health care system. Someone who is self-managing a medication abortion can source pills through a US-based or international website that sells abortion pills or, less commonly, through a community network. For those who live in a state where abortion has been banned, another option (discussed below) may be accessing pills from a licensed health care provider practicing in a state where abortion is not banned, creating a blurry line between self-managed abortion and the use of telemedicine. Further blurring the line, new research has documented that tens of thousands of people are requesting a prescription for abortion pills before potentially needing them, known as advance provision. Many individuals who later get pregnant and take the medication will be undertaking a self-managed abortion.

Having an abortion outside the formal health care system does not mean patients are necessarily alone. There are varying models to support people self-managing a medication abortion, from community networks that provide virtual support during the process to hotlines staffed by clinicians to abortion doulas and more. The experience of a self-managed abortion may be similar to the process with a licensed US telemedicine provider, although there are different legal risks.

Criminalizing abortion

Despite the patchwork of abortion bans and restrictions across the country, which come with the threat of stiff penalties for health care providers who violate any of those laws, it is not illegal in most places for pregnant people to manage their own abortions. Only Nevada explicitly bans self-managed abortion, and it does so only after 24 weeks of pregnancy. Despite that, the legal landscape is murky, and the threat of being criminally investigated or arrested for self-managing an abortion is real. The risk is particularly high for people from communities disproportionately targeted by the criminal justice system, including people living with low incomes, Black and Brown communities and other people of color, immigrants and young people.

Law enforcement officials in many states have chosen to prosecute people after suspecting that they self-managed an abortion. An analysis from the legal organization If/When/How identified 61 cases from 2000 to 2020 of people being criminally investigated or arrested for allegedly ending their own pregnancy or helping someone to do so. The analysis revealed that prosecutors often misapplied a variety of criminal laws—from practicing medicine without a license to child abuse to homicide—in order to punish someone for self-managing an abortion. Regardless of each case’s outcome, the person being prosecuted often faced serious and long-lasting ramifications from the investigation. The threat of criminalization for self-managed abortion further perpetuates abortion stigma and health care inequities, and it has created a climate of fear and distrust.

Introduction of shield laws

In response to the growing legal threats against providers as well as patients, 22 states and the District of Columbia (as of December 2023) have enacted policies to protect abortion providers, and sometimes patients and support organizations, from investigations in other states. Known as “shield laws,” these policies vary from state to state and have been implemented via executive order, statute or both. For example, in some states, the policy prevents a licensed health care professional who may provide an abortion to a patient who has traveled from another state from sharing the patient’s health care information with anyone in the person’s home state if the information could put the patient in legal jeopardy. Other shield laws prohibit state officials or licensing bodies from cooperating with an out-of-state investigation into the provision of abortion care or limit adverse consequences related to health care providers’ professional licenses if they provide reproductive health care that is criminalized in another state but legal in their own state.

As a result of shield laws, it is now possible for people who live in any state, including those where abortion is banned, to obtain medication abortion drugs from US health care providers. However, these laws do not necessarily provide legal protections for someone receiving the medication, and they are largely untested legally. The result may be a type of self-managed medication abortion where the provider is embedded in the formal health care system and protected by a shield law, but a threat of criminalization remains for individuals who use the medication in states where abortion is banned.

Ensuring Full Access to Medication Abortion

Everyone seeking abortion care should have access to the full range of safe, effective options so they have freedom in choosing the method they feel is right for them—without shame, stigma or fear of legal repercussions. Individuals who seek abortion care through a health care provider should have access to the provider of their choice, in a manner that is accessible, convenient and affordable. Individuals who self-manage their medication abortion should have access to the information they need to feel safe and comfortable and to a health care provider if they need or want one at any stage.

Federal and state policies need to support that vision. In addition to removing medically unnecessary restrictions on abortion in state and federal law, policies need to support full access to abortion care, including medication abortion. States with policies supportive of abortion rights must redouble their efforts to further codify, reinforce and expand those protective policies. Congress must pass federal laws that provide abortion access, like the Equal Access to Abortion Coverage in Health Care (EACH) Act, the Women’s Health Protection Act and the Abortion Justice Act. The EACH Act would ensure coverage for abortion—no matter how much someone earns, their type of insurance or where they live. The Women’s Health Protection Act would protect access to abortion by establishing a right under federal law to deliver and receive abortion care, including medication abortion, without medically unnecessary restrictions and bans. The Abortion Justice Act includes provisions that support the full spectrum of care around abortion services, including protection for patients and providers from criminalization.

There should be both a legal right and guaranteed access to abortion across the country for anyone in need. Medication abortion has proven to be a game changer in expanding abortion care in the United States, and it will continue to be an important option, especially as states continue to ban and otherwise restrict abortion access.

Correction Note (April 2, 2024)

The original analysis erroneously listed Arizona as having a current statutory provision that requires medical personnel to inform patients that they can “reverse” a medication abortion. At the time of publishing, that provision had been amended and no longer mentioned reversal. The text and graphic have been revised accordingly.

Correction Note (February 8, 2024)

The original analysis erroneously reported four states (MT, IA, KS, OH) as having medication abortion restrictions in effect when those policies are temporarily or permanently enjoined. Montana was incorrectly listed as requiring an in-person visit with a physician, banning the mailing of abortion pills and requiring that patients be notified about “reversal” of medication abortion. All policies restricting medication abortion in Montana are currently blocked; thus, the total number of states with medication abortion restrictions in effect is 29, not 30 as originally published. Iowa, Kansas and Ohio were incorrectly listed as having an in-person physician visit requirement in effect; these policies are also blocked. The text and graphic have been revised accordingly.