Revised April 3, 2019

- Access to contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care is critical for women’s health, as well as their social and economic well-being.

- In 2017, the Nigerian government committed to achieving a modern contraceptive prevalence rate of 27% among all women aged 15–49, regardless of marital status, by 2020.1

- The Nigeria Ministry of Health also made commitments to improve sexual and reproductive health and maternal and child health outcomes. It pledged to ensure that by 2021, 80% of pregnant women will attend at least four antenatal care visits, 54% of births will take place in a health facility and the contribution of unsafe abortion to maternal mortality will be reduced to 2% or less.2

- Increased investment is essential to ensure that Nigeria’s commitments are met and that women have access to the information and services they need to determine whether and when to become pregnant.

Lack of essential contraceptive services

- Of the 45 million women of reproductive age (15–49) in Nigeria, 15.7 million want to avoid a pregnancy; that is, they are able to become pregnant, are married or are unmarried and sexually active, and do not want a child for at least two years.

- Some 6.2 million (14% of all women of reproductive age) use modern contraceptives. The largest share of modern method users rely on male condoms (43%), followed by injectables (21%) and oral contraceptive pills (16%).3

- Women wanting to avoid a pregnancy who are not using a modern method are considered to have an unmet need for modern contraception. Of the 9.5 million women with unmet need, 7.0 million use no contraceptive method and 2.5 million use traditional methods, which typically have low levels of effectiveness.

- Among women wanting to avoid a pregnancy, the proportion with an unmet need for modern contraception is much higher among women living in households in the poorest wealth quintile than among women living in households in the richest quintile (92% versus 45%).

Lack of essential maternal and newborn health services

- Of the estimated 10.3 million pregnancies in Nigeria, 24% were unintended (i.e., unwanted or not wanted in the next two years). Women with an unmet need for modern contraception accounted for 90% of all unintended pregnancies.

- More than half of unintended pregnancies in Nigeria end in abortion.

- Many of the 7.4 million women who give birth each year do not receive the essential components of maternal and newborn care recommended by the World Health Organization and the Nigeria Ministry of Health. For example, 50% do not receive a minimum of four antenatal care visits, and 63% do not give birth in a health facility.

The large majority of women living in households in the poorest wealth quintile did not receive a minimum of four antenatal care visits (84%) and did not deliver at a health facility (94%). In contrast, 12% of women living in households in the richest quintile did not receive four antenatal care visits and 19% did not deliver at a health facility.

- Each year in Nigeria, 61,000 women die from complications of birth, abortion or miscarriage, and 255,000 newborns die in the first month of life. Most of these deaths could be prevented with adequate medical care.

- Of the two million women and 2.8 million newborns in Nigeria who require care for medical complications related to pregnancy and delivery, only 17% receive the care they need.

- Abortion is only legal in Nigeria if performed to save a woman’s life. Of the 1.3 million abortions in 2018, 85% are estimated to occur under unsafe conditions.*,4

Health benefits of meeting women’s need for services

- If all unmet need for modern contraception in Nigeria were satisfied, unintended pregnancies would drop by 77%, from 2.5 million to 555,000 per year. As a result, the annual number of unplanned births would decrease from 885,000 to 200,000 and the number of abortions would drop from 1.3 million to 287,000.

- If full provision of modern contraception were combined with adequate care for all pregnant women and their newborns, maternal deaths would drop by 68% (from 61,000 to 19,000 per year) and newborn deaths would drop by 85% (from 255,000 to 38,000 per year).

Cost of contraception and maternal and newborn care

- The 2018 estimated annual cost of providing contraceptive services to the 6.2 million women of reproductive age in Nigeria who are currently using modern methods is US$67 million. This includes direct service costs for drugs, supplies and personnel, as well as estimated indirect (program and systems) costs.

- Meeting the need for modern contraception among all women in Nigeria who want to prevent a pregnancy would cost $546 million annually, an increase of $478 million over current costs. This additional investment would provide improved quality of care for current users and coverage for new users.

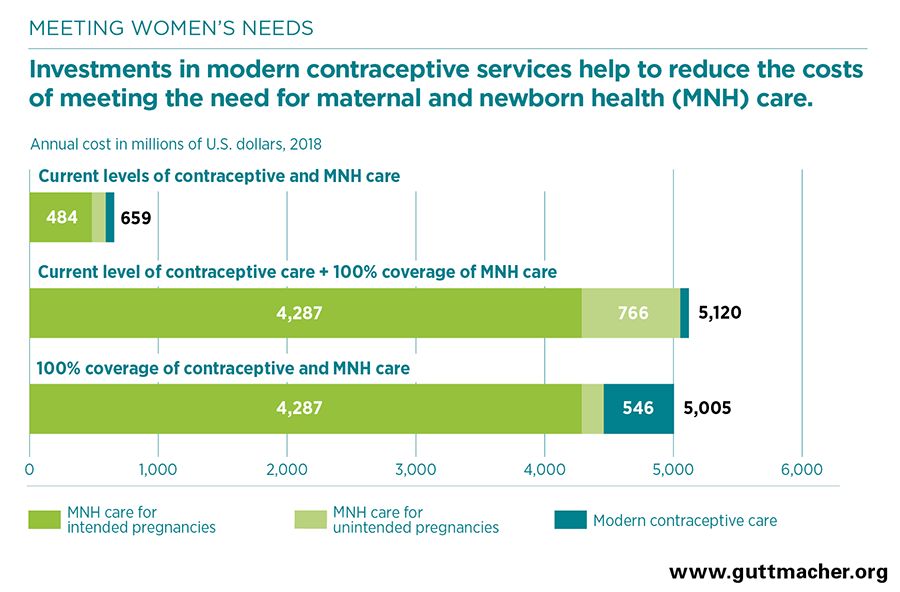

- Maternal and newborn care at current levels costs $591 million annually—$484 million for care related to intended pregnancies and $107 million for care related to unintended pregnancies. Fully meeting the current need for maternal and newborn care without increasing contraceptive use would cost $5.1 billion annually. However, if all need for both contraception and maternal and newborn health care were met, the cost of maternal and newborn care would be reduced to $4.5 billion.

- Because the cost of preventing an unintended pregnancy through use of modern contraception is far lower than the cost of providing care for an unintended pregnancy, for each additional dollar spent on contraception would reduce the cost of maternal and newborn health care in Nigeria by $1.24.

- Fully meeting women’s needs for both contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care in Nigeria would cost a total of $5.0 billion each year—$26.09 per capita—a total that is roughly the same cost as meeting the need for maternal and newborn care alone.

Recommendations

- Invest in meeting the need for modern contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care to improve health outcomes. Investing in both sets of services is more cost-effective than focusing on maternal and newborn health alone. In addition, it has enormous benefits for women, families and society, and it would likely contribute to Nigeria’s progress towards achieving goals set at the national, regional and global levels.

- Increase access to sexual and reproductive health information, supplies and services, particularly for young people, unmarried women and those living in poorer households.5,6

- Invest in public-private partnerships, in which privately run facilities are supported by the government to provide high-quality, comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services; and drug stores are supported to provide some modern contraceptive methods at a more affordable cost.7

- Implement health worker trainings and health system upgrades focused on ensuring the provision of high-quality and respectful services across the spectrum of sexual, reproductive and maternal health care for all women.8