- Ugandan law explicitly allows abortion only to save a woman’s life. In addition, national guidelines permit abortion in cases of fetal anomaly, rape or incest, or if the woman is HIV-positive.

- However, it is difficult for women seeking abortion, as well as the medical community, to understand when abortion is permitted because existing laws and policies on abortion are interpreted inconsistently by law enforcement and the judicial system. Because of this ambiguity, medical providers are often reluctant to perform an abortion for any reason, out of fear of legal consequences.1

- Worldwide, restrictive laws (like Uganda’s) do not necessarily prevent abortion. Instead, they contribute to fear of imprisonment and stigma and tend to drive women to clandestine, and potentially unsafe, procedures.

- More than 93,000 women were hospitalized for complications from unsafe abortion in Uganda in 2013, and more than 10% of the country’s maternal deaths are due to unsafe abortion.

ABORTION INCIDENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS

- Approximately 57,000 abortions took place among adolescents aged 15–19 in Uganda in 2013.

- While adolescents made up 25% of the reproductive-age population, they accounted for only 18% of abortions.

- Overall, the adolescent abortion rate was lower than that among all women of reproductive age (28 per 1,000 women aged 15–19 vs. 39 per 1,000 women aged 15–49). Among women who were recently sexually active, however, adolescents had the highest abortion rate (76 vs. 56, respectively).

- At 15%, the proportion of pregnancies ending in abortion in 2013 was similar across age-groups. The comparatively high abortion rate among sexually active adolescents is likely explained by the difficulties they face in obtaining information and services related to family planning; such barriers put them at heightened risk of unintended pregnancy.

POSTABORTION CARE AMONG ADOLESCENTS

- In 2013, adolescents who sought postabortion care (i.e., treatment for complications from an unsafe abortion or miscarriage) were no more likely than postabortion care patients older than 20 to have been past their first trimester of pregnancy, to report delays in seeking postabortion care or to experience severe complications.

- Adolescents seeking postabortion care were more likely than older women who sought postabortion care to be unmarried (81% vs. 46%) and have secondary education (43% vs. 31%).

- Among postabortion care patients, unmarried women, including unmarried adolescents, were more likely than married women to have experienced severe complications.

CONTRACEPTION AND UNMET NEED

- According to data from 2016, the level of unmet need for modern contraception in Uganda was higher among sexually active unmarried adolescents (45%) than among married adolescents (30%).

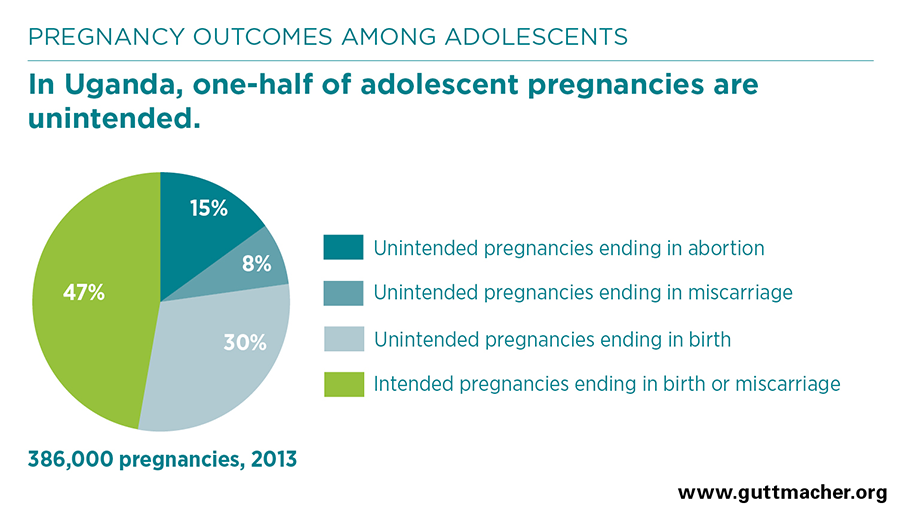

- Half of pregnancies among adolescents aged 15–19 were unintended in 2013, and 15% ended in abortion.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Data suggest that among women seeking postabortion care, unmarried women, including unmarried adolescents, may be at elevated risk of experiencing severe complications from unsafe abortion or miscarriage. More effective sexual and reproductive health policies and programs are critically needed to address the sexual and reproductive health needs of sexually active, unmarried adolescent women.

- Access to family planning and to comprehensive sexuality education that is both age-appropriate and medically accurate should be made available to all adolescents to help them prevent unintended pregnancy.