Originally published on Health Affairs Blog.

The immediate economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating in the United States, and particularly for younger women and women of color, who thus far have been hit hardest by job losses. And because health insurance is tied to employment for about half of the US population—some 160 million people—losing a job may mean losing insurance. As job losses mount, millions will likely end up uninsured, and millions more will turn to publicly supported insurance such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and government-subsidized coverage on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces.

A new Guttmacher Institute analysis helps illustrate that this upheaval in employer-sponsored insurance can be expected to have substantial consequences for people seeking sexual and reproductive health care and for the providers and programs supporting that care. Specifically, millions of people will need to find new insurance plans or end up uninsured. Publicly supported clinics and insurance programs will be asked to serve more people and face new financial and logistical pressures—pressures that compound years of weakening of family planning clinics and programs with sustained political attacks by opponents of reproductive rights.

The Pandemic’s Economic And Health Insurance Fallout

According to an analysis of federal employment data, the National Women’s Law Center estimates that women have accounted for 56 percent of total job losses since the start of the pandemic, in large part because women are overrepresented in the types of jobs that are being hit hardest, such as retail, restaurant, and education jobs, and part-time, low-paid, and tipped jobs more generally. Women’s unemployment rate in May 2020 (13.9 percent) was higher than among men (11.6 percent) and higher than at its peak during the Great Recession of 2007–09 (8.4 percent). Unemployment rates were even higher than the average in May for Black (16.5 percent) and Latina (19.0 percent) women, women with disabilities (20.3 percent) and women ages 20–24 (24.0 percent).

Moreover, economists have made it clear that these measures of unemployment understate the full extent of the harm because they do not account for furloughs or reduced hours, wages, or benefits. And we have every reason to expect that this situation will persist, given the apparent longevity of the pandemic and its continued effects on the US economy.

The connection between rising unemployment and loss of health insurance has received considerable attention during the pandemic. According to modeling from the Urban Institute drawing on experiences during the Great Recession, a 20 percent unemployment rate would result in the loss of employer-sponsored insurance among 16 percent of those previously insured by such plans. More than one-quarter of those losing coverage through an employer would remain uninsured, while nearly half would be able to obtain new coverage through Medicaid or CHIP (which covers many adolescents and pregnant women) and one-quarter by purchasing insurance directly, such as through the ACA Marketplaces.

Predictably, the situation would be considerably worse in the 14 states that have not adopted the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In those states, the Urban Institute estimates that 40 percent of people losing employment-sponsored insurance will remain uninsured, compounding the already high rate of uninsured people in those states. Among women of reproductive age, uninsured rates in nonexpansion states were already twice as high as in expansion states as of the most recent available data from 2018.

Impact On Women

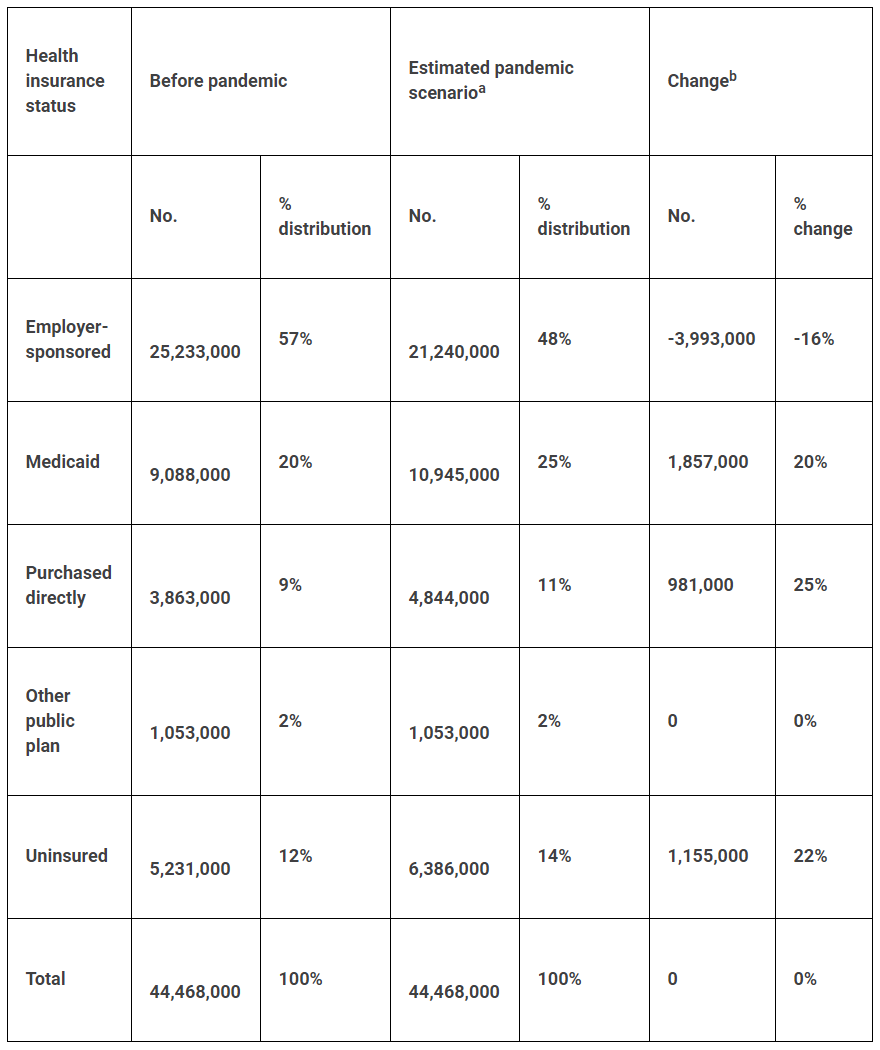

A new Guttmacher Institute analysis demonstrates that the broader economic and insurance upheavals brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in widespread harm to people’s sexual and reproductive health. Based on the most recent data available from the National Center for Health Statistics’ National Survey of Family Growth (2015–17), a nationally representative survey of reproductive-age people, an estimated 44.5 million women ages 15–44 received sexual or reproductive health care in the 12 months preceding their interview. This segment of survey respondents were identified as women and had received contraceptive services, cervical cancer screening, sexually transmitted infection (STI)-related services, or pregnancy-related care. Among those women, 57 percent (25.2 million) had insurance through their own job or a family member’s job.

Based on a 20 percent unemployment rate and Urban Institute’s modeling of the resulting loss of health insurance coverage, we estimated that four million women who received sexual and reproductive health care in the past year would lose their employer-sponsored insurance (see exhibits 1 and 2). This affects nearly one in 10 of all women who obtain sexual and reproductive health care. Out of this 4.0 million total, our modeling estimates that 1.9 million women would shift to Medicaid or CHIP, 981,000 would shift to purchasing insurance directly, such as through the ACA’s health insurance Marketplaces, and 1.2 million would remain uninsured.

Exhibit 1: Actual and estimated health insurance status of women obtaining any sexual or reproductive health service prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Sources: Estimates of impact from 20 percent unemployment on employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) and estimates of what those losing ESI will do for insurance, see Garrett G, Gangopathyaya A. How the COVID-19 recession could affect health insurance coverage. Washington (DC): Urban Institute, 2020 May. Data for women obtaining sexual and reproductive health services, special tabulations of data from the 2015–17 National Survey of Family Growth. aAssumes 20 percent unemployment rate, based on Urban Institute modeling. bBased on Urban Institute model, we assumed that among those losing ESI, 46.5 percent will enroll in Medicaid, 24.6 percent will purchase insurance directly, and 28.9 percent will remain uninsured.

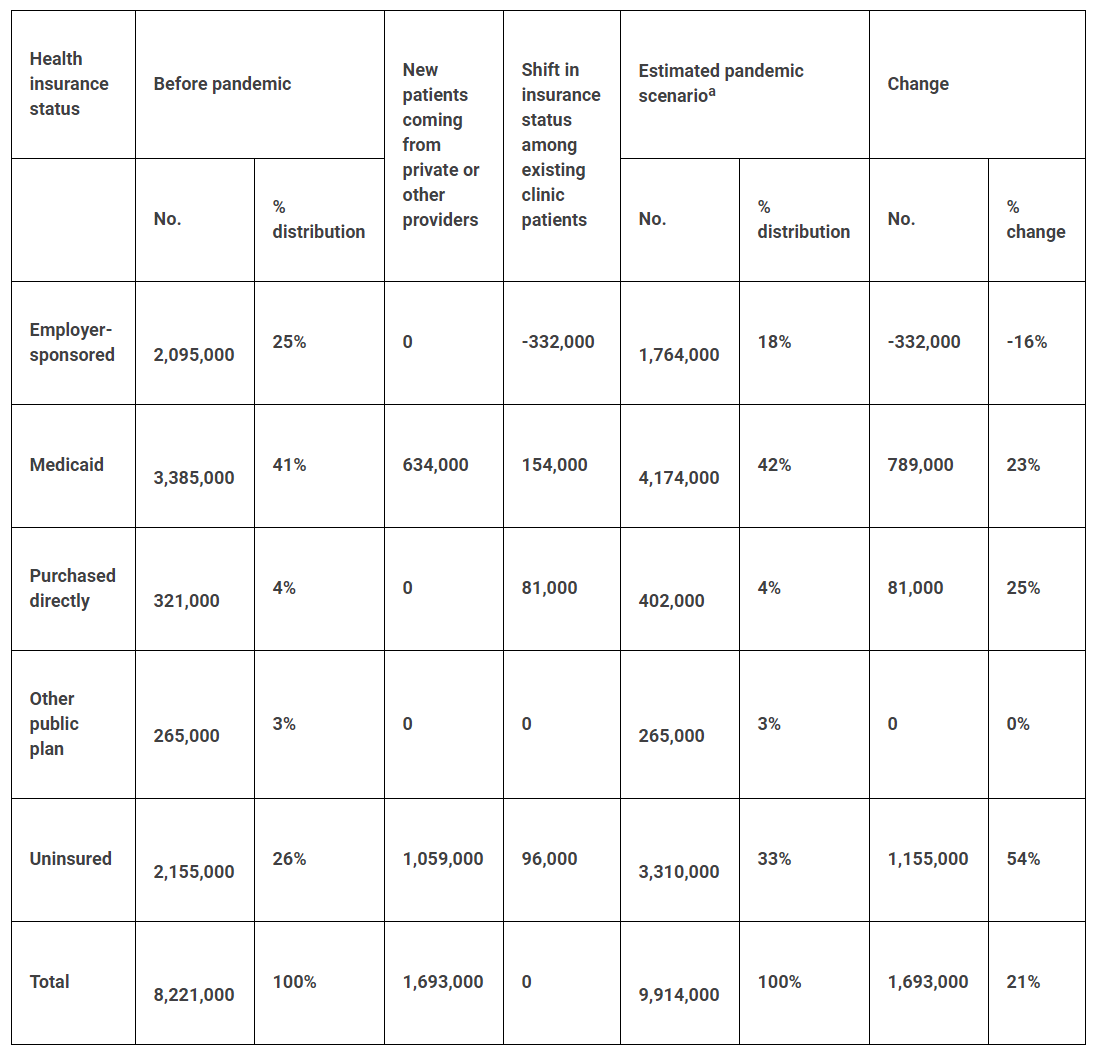

Exhibit 2: Actual and estimated numbers of women obtaining sexual or reproductive health services at publicly funded health clinics, according to insurance status, prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Sources: Estimates of impact from 20 percent unemployment on employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) and estimates of what those losing ESI will do for insurance, see Garrett G, Gangopathyaya A. How the COVID-19 recession could affect health insurance coverage. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2020 May. Data for women obtaining sexual and reproductive health services and estimates of where women newly enrolled in Medicaid will seek care, special tabulations of data from the 2015–17 National Survey of Family Growth. aModel estimates assume: All women who lose ESI and purchase insurance directly will stay with current provider; all women who lose ESI and become uninsured who previously went to private or other providers will switch to publicly supported clinics; and 37 percent of women who lose ESI and shift to Medicaid who previously went to private or other providers will switch to clinics.

It is unclear which groups of women would be hit hardest by loss of their health insurance. Unfortunately, the Urban Institute model that our analysis relies on does not include projections based on sex, race, ethnicity, income, or other characteristics. Moreover, reality seems to pull in opposite directions: For example, lower-income women, Black and Latina women, and immigrant women are less likely than their higher income, white and US-born counterparts to rely on employer-sponsored insurance and private clinicians currently, but they are also more likely to lose their job and insurance because of the pandemic. Nevertheless, these groups and others who have been traditionally marginalized in the United States, including LGBTQ+ individuals, will surely face high hurdles to securing insurance coverage and sexual and reproductive health care.

For women losing employer-sponsored insurance, the resulting barriers to care may negatively affect their health and well-being. For example, they may end up uninsured and have to make decisions based on financial constraints rather than their health, such as decreasing contraceptive use and use of preventive gynecologic care. They may also lose access to a trusted health care provider and be forced to find a new provider—a task that can be particularly daunting in rural areas and for people seeking a provider who is culturally or linguistically competent, or responsive to the specific needs of LGBTQ+ or young people.

Impact On Clinics

Guttmacher’s analysis also assesses the potential impact of job and health insurance losses on the publicly supported clinics providing sexual and reproductive health services. For this analysis, we assumed that 100 percent of women who remain uninsured after losing employer-sponsored insurance would turn to publicly supported clinics for their sexual and reproductive health care because they would have lost their income along with their insurance and likely would not be able to afford care from a private provider. We also assumed that 37 percent of women newly insured by Medicaid or CHIP would seek care from publicly supported clinics, which would be in line with current patterns for women insured by these programs (based on special tabulations of data from the 2015–17 National Survey of Family Growth).

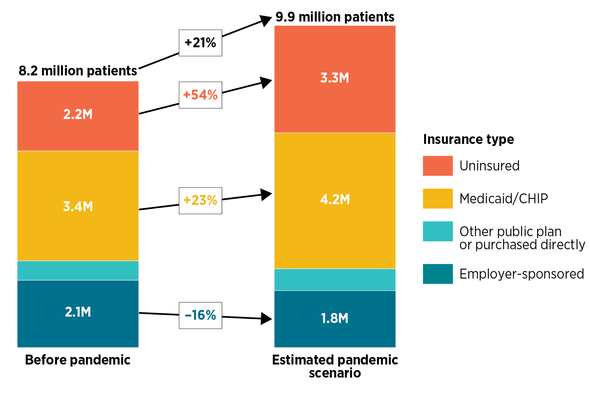

As a result of women losing employer-sponsored insurance, we estimated that publicly supported clinics would be asked to take on 1.7 million additional sexual and reproductive health care patients, a 21 percent increase above the numbers they were already serving (exhibit 3). Serving so many new patients would place substantial financial and logistical demands on clinics. This assumes clinics are even capable of taking on so many new patients—an assumption that is highly questionable, given all of the pressures clinics are currently facing.

Exhibit 3: Change in numbers of women obtaining sexual or reproductive health services at publicly funded health clinics, according to insurance status, prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: Original analysis by the Guttmacher Institute using data from the National Survey of Family Growth and the Urban Institute. Note: CHIP is Children’s Health Insurance Program.

In addition, we estimate that clinics would face major shifts in how their patients’ care is reimbursed. Specifically, we estimate a 16 percent decline (n = 332,000) in the number of patients with employer-sponsored insurance, the type of insurance that reimburses clinics at the highest rates for their services. At the same time, clinics would see a 23 percent increase (n = 789,000) in the number of patients insured through Medicaid or CHIP, which typically offer lower reimbursement rates than private insurance. Clinics would see a 54 percent increase (n = 1.2 million) in the number of uninsured patients and would have to cover the cost of that care with limited grant funding.

These new financial and logistical demands—if they could be met by clinics at all—would be compounded by other pandemic-related stresses on clinics. Public health departments and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), which collectively provide sexual and reproductive health care to 50 percent of the women served by the publicly supported family planning clinic network, have shifted resources to provide COVID-19 screening, testing, and treatment. For example, a June survey from the National Association of Community Health Centers, which represents FQHCs, found that 93 percent of health centers had COVID-19 testing in place, and 74 percent had walk-up or drive-up testing capabilities. Health departments have also taken on the financial, staffing, and logistical burdens of contact tracing and other pandemic-related public health activities.

At the same time, these clinics are losing revenue from other sources. Health departments rely on state and county funding, which has been hit hard by the new recession, loss of tax revenue, and competing pandemic-related priorities, all of which may get worse. Clinics are also seeing fewer preventive and primary care visits (which typically bring in consistent revenue) because of stay-at-home orders and patient concerns about exposure to the coronavirus. The National Association of Community Health Centers projects a 60 percent decline in FQHC visits over six months, which could lead to $7.6 billion in lost revenue.

Meanwhile, all of these new pandemic-related demands for service come on top of already massive strains on the national family planning clinic network. The Title X national family planning program has been devastated by the Trump administration’s so-called "domestic gag rule," which prohibits abortion referrals, interferes with counseling for pregnant patients, and imposes other burdensome requirements on clinics. In 2019, the gag rule led nearly one in four Title X service providers—including all Planned Parenthood–affiliated grantees—to leave the program, which reduced the network’s capacity to serve patients by a staggering 46 percent.

Impact On Public Programs

In addition to the strain on clinics, the pandemic is also adding stress to Medicaid, CHIP, and other public health insurance programs, which insure people with low incomes for whom private health insurance is typically unaffordable. Medicaid is designed to be responsive to a recession, so that more people become automatically eligible for coverage as the economy worsens. Unfortunately, although the federal government is able to take on additional costs by borrowing money during a recession, almost every state government is required to balance its budget and does not have that option. One of Congress’s initial COVID-19 relief packages gave states a temporary Medicaid funding boost. So far it amounts to about half of the relief provided to states during the Great Recession, even though the current recession is on track to be worse than that. Many states are already expecting Medicaid budget shortfalls.

Then there are the 14 states that have not adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion—despite numerous studies demonstrating that the expansion has led to improvements in sexual and reproductive health and other health care access and outcomes, including reductions in maternal mortality, and has had economic benefits for individuals, providers, and also states themselves. Beyond that, federal officials and conservative state policy makers have worked to reshape Medicaid in fundamentally harmful ways, such as by proposing unprecedented caps on federal funding for the program.

For all of these reasons, it is simply not clear whether the millions of additional people who will turn to Medicaid for sexual and reproductive health care as they lose their jobs and health insurance during the pandemic will receive the coverage and care they need. Congress’s relief package requires states accepting the additional Medicaid funding to refrain from decreasing eligibility standards, raising premiums, or kicking people off the program. Yet, some states are finding other ways to cut back on Medicaid spending, such as reducing benefits to enrollees or payments to providers, and some state policy makers are lobbying Congress to relax its requirements.

Policy Recommendations

There are a number of actions federal and state policy makers should take to cushion the likely negative outcomes for people’s sexual and reproductive health from the COVID-19 pandemic. To begin with, given the current widespread reliance on employer-sponsored insurance, they should be working to minimize economic consequences, wherever possible, through funding and other support for workers and businesses. These efforts should focus on historically marginalized groups who are, predictably, being hit hard by unemployment, such as people of color, people with low incomes, immigrants, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with disabilities. These same groups have also been affected more than others by lack of paid leave time, child care, and transportation.

Policy makers should also ensure that people who lose their employer-sponsored insurance can readily secure new health coverage. That means investing in Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidized ACA Marketplace coverage by expanding eligibility for these programs and revisiting outreach and enrollment practices to ensure that people can easily learn about their eligibility and enroll with minimal red tape. To ensure that these programs can handle an influx of new enrollees, Congress should boost federal funding to supplement declining state revenue.

In addition, policy makers should invest in publicly supported clinics that provide family planning services, so that people in economic distress because of the pandemic will have a place to go for care. That includes supporting outreach efforts to help people find local family planning clinics that can meet their sexual and reproductive health needs. And it means providing those clinics with additional funding to meet their multiple financial challenges and stay afloat, as well as offering technical assistance to help them operate via telehealth and otherwise protect patients and staff from coronavirus exposure. To the extent that state policy makers impose stay-at-home orders and other restrictions on commerce and travel as the pandemic unfolds, they should treat sexual and reproductive health services and providers equally with other essential care.

People also need alternatives to in-clinic services, especially during this pandemic. Policy makers should invest in service provision methods that are particularly salient for people worried about coronavirus exposure or unable to travel to a clinic. For example, policy makers should continue to remove restrictions on telehealth and facilitate its wider adoption for sexual and reproductive health care. They should also eliminate barriers to at-home STI testing and receiving contraceptives and other sexual and reproductive health–related drugs and supplies via mail order and at pharmacies without a prior prescription. Policy makers should institutionalize these innovations, as they could significantly lower barriers to obtaining sexual and reproductive health care for many people after the pandemic eases.

Many marginalized groups face a range of additional social, economic, and political barriers to sexual and reproductive health services that have been magnified during the pandemic, and which policy makers should address to insure greater equity. For example, policy makers should invest in additional interpretation and translation services for people with limited English proficiency. They should help clinics and insurance programs meet the specific health care and support needs of people with disabilities, such as accessible transportation services. Policy makers should eliminate discriminatory policy barriers to immigrants’ health insurance coverage and access to care, both during the current pandemic and beyond. More broadly, policy makers should enforce protections against discrimination, including the ACA’s Health Care Rights Law, to protect people from discrimination from health care providers and insurers based on race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, age, gender identity, disability, and other characteristics.

As our estimates illustrate, sexual and reproductive health care patients and providers are navigating a difficult new reality during the COVID-19 pandemic that has magnified existing burdens and inequities. Publicly supported clinics and public health insurance programs may be able to rise to these challenges and help people get the sexual and reproductive health care they need, but these efforts will be hamstrung without the strong support of federal and state policy makers.