- Improving adolescents’ sexual reproductive health and rights, including preventing unintended pregnancy, is essential to their social and economic well-being.

- Adolescent women aged 15–19 make up almost one-quarter of the female population in Ethiopia,1 and they account for 12% of all births.2 Almost half of pregnancies among adolescents in Ethiopia are unintended, and 46% of those unintended pregnancies end in abortion.3

- Complications of pregnancy and childbirth continue to lead to preventable deaths and ill health among 15–19-year-old women in Ethiopia.

- The 2005 expansion of Ethiopia’s abortion law increased access to safe, legal abortion services, including for adolescent women. The majority (64%) of adolescent women who have an abortion obtain it legally. The proportion of women obtaining legal (rather than clandestine) abortions is highest among adolescents, compared with older age-groups. Despite notable gains in reducing unsafe abortion, many Ethiopian adolescents continue to experience complications from unsafe abortions.3 One-third of all abortions in the country take place outside of health facilities and are potentially unsafe.

- In 2017, the Ethiopian government committed to improving the health status of adolescents by coordinating efforts to strengthen adolescent- and youth-friendly services and improve access to contraception for adolescents.4 However, increased investment is essential to ensure that adolescents have access to the information and services they need to determine whether and when to become pregnant.

Adolescents’ need for contraception and maternal and newborn health care

- Of the 6.2 million women aged 15–19 in Ethiopia in 2018, 13% (778,000) have a need for contraceptive methods; that is, they are married, or are unmarried and sexually active, and do not want a child for at least two years.

- Among these 778,000 adolescent women, 63% (494,000) are using modern contraceptives. The most common method among modern contraceptive users is injectables (91%). Almost all of the remaining 9% use implants.

- More than a third (37%) of sexually active adolescent women in Ethiopia who do not want to become pregnant—284,000 in 2018—have an unmet need for modern contraception. These adolescents either use no contraceptive method or use traditional methods, which typically have low levels of effectiveness. Ninety percent of all adolescent unintended pregnancies in the country occur among this group.

- Unmet need for modern contraception is higher among married adolescent women than among unmarried, sexually active adolescent women (39% versus 26%).

- Few of the 323,000 adolescent women who give birth each year receive the essential components of maternal and newborn care recommended by the World Health Organization and the Ethiopian Ministry of Health. For example, only 15% have four or more antenatal care visits and only one in 10 give birth in a health facility.

Benefits of meeting contraceptive and maternal health needs

- If all unmet need for modern contraception among adolescents in Ethiopia were satisfied, unintended pregnancies would drop by 88%, from 221,000 per year to 26,000 per year, resulting in reductions in the annual numbers of unplanned births (from 111,000 to 13,000) and abortions (from 80,000 to 10,000).

- Likewise, in the scenario in which all unmet need for modern contraception among adolescents in Ethiopia is met, adolescent maternal deaths would drop by 33% (from 1,000 per year to 670 per year). If full provision of modern contraception were combined with adequate care for all pregnant adolescents and their newborns, adolescent maternal deaths would drop by 82% (from 1,000 per year to 180 per year).

Need for greater investment

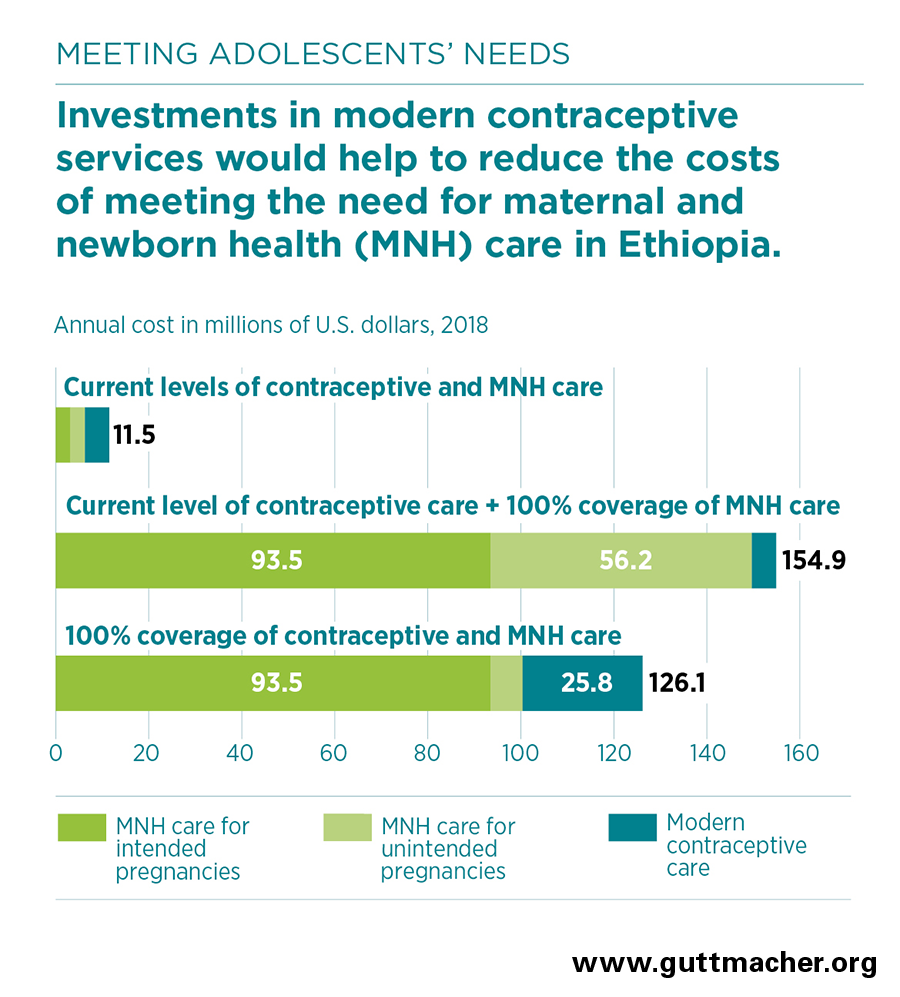

- The 2018 estimated annual cost of providing contraceptive services to the 494,000 women aged 15–19 in Ethiopia who currently use modern contraceptives is $5 million. This averages $10.52 per user annually.

- The total cost in 2018 for maternal and newborn health care services for all adolescents who become pregnant and their newborns is $6 million.

- Meeting the need for modern contraception among all adolescent women in Ethiopia who are sexually active and want to avoid having a child in the next two years would cost $26 million annually, an increase of $21 million from the current cost. This additional investment would provide improved quality of care for current users and coverage for new users.

- In the absence of this additional investment in contraceptive services, fully meeting the current need for maternal and newborn care for adolescent women would cost an estimated $150 million annually, of which $56 million would go to care related to unintended pregnancies.

- Fully meeting adolescents’ need for modern contraception would lower pregnancy-related costs by $49 million, to $100 million.

- Because the cost of preventing an unintended pregnancy through the use of modern contraceptives is far lower than the cost of providing care for an unintended pregnancy, each additional dollar spent on contraceptive services for adolescents would reduce the cost of maternal and newborn health care for adolescents in Ethiopia by $2.40.

- Fully meeting the needs for both modern contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care for adolescents in Ethiopia would cost a total of $126 million each year.

- Annually, it would cost $1.18 per capita to fully meet adolescent women’s needs for both modern contraception and maternal and newborn care in Ethiopia ($0.24 per capita on modern contraception and $0.94 on maternal and newborn care).

- The return on these investments goes beyond the critical impacts on health to include broad social and economic benefits for adolescent women and society, such as increases in women’s education and earnings, which can lead to overall reductions in poverty. Ensuring adolescents stay healthy and providing them with economic opportunities and education so they can decide if and when to have children is a critical step toward achieving the benefits of a demographic dividend.

Recommendations

- Investing in meeting the need for both modern contraception and maternal and newborn health care among adolescents in Ethiopia is essential to improving health outcomes, and it is more cost-effective than focusing on maternal and newborn health care alone.

- The most effective actions to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health take a multifaceted and coordinated approach and provide access to services that are nondiscriminatory; medically accurate; and developmentally, culturally and age-appropriate. The following bullets describe some of these approaches.

- Improve access to and quality of adolescent and youth-centered health services, especially for more vulnerable groups such as adolescents with disabilities and married, rural, poor and less educated adolescents.5,6

- Increase information about these services within communities and schools through programs that seek to change stigmatizing social norms around access to youth sexual and reproductive health services. This could be done through the Ethiopia School Health Program.7

- Implement health worker trainings and health facility improvements focused on ensuring the provision of quality and respectful sexual and reproductive health services.