Revised April 3, 2019

- Access to contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care is critical for women’s health, as well as their social and economic well-being.

- In 2017, the Ethiopian government committed to making contraceptives available to all who want them, with the specific goal of increasing the modern contraceptive prevalence rate to 55% among married women by 2020.1

- In 2015, the Ministry of Health also set targets for increasing the use of interventions that reduce maternal and neonatal mortality. These included increasing the proportion of women receiving at least four prenatal care visits to 95% and increasing the proportion of deliveries with a skilled birth attendant to 90% by 2020.2

- The 2005 expansion of Ethiopia’s abortion law increased access to safe, legal abortion services.3

- Increased investments in contraception and maternal and newborn health are essential to ensure that women have access to the information and services they need to determine whether and when to become pregnant.

Lack of essential contraceptive services

- Of the 27 million women of reproductive age (15–49) in Ethiopia, 11.7 million (44%) want to avoid a pregnancy; that is, they are able to become pregnant, are married or are unmarried and sexually active, and do not want a child for at least two years.

- Among these 11.7 million women, 7.2 million (61%) use modern contraceptives. The majority of modern contraceptive users rely on injectables (64%), and the next highest proportions of modern method users rely on implants (23%) and IUDs (6%), both of which are long-acting, reversible methods.

- Women wanting to avoid a pregnancy who are not using a modern method are considered to have an unmet need for modern contraception. Of the 4.5 million women with unmet need, 4.4 million use no contraceptive method and 143,000 use traditional methods, which typically have low levels of effectiveness.

- Among women wanting to avoid a pregnancy, the proportion with an unmet need for modern contraception is much higher among women living in households in the poorest wealth quintile than among women living in households in the richest quintile (57% versus 26%).

- Unmet need for modern contraception is also higher among women wanting to avoid pregnancy who live in rural areas than among those living in urban areas (42% versus 22%).

Lack of essential maternal and newborn health services

- Of the estimated 4.6 million pregnancies in Ethiopia, 46% are unintended (i.e., unwanted or not wanted in the next two years). Women with an unmet need for modern contraception account for 93% of all unintended pregnancies.

- One in four unintended pregnancies in Ethiopia end in abortion.

- Many of the 3.3 million women who give birth each year do not receive the essential components of maternal and newborn care recommended by WHO and the Ethiopia Ministry of Health. For example, 67% do not receive a minimum of four antenatal care visits, and 66% do not give birth in a health facility.

- The large majority of women living in households in the poorest wealth quintile do not receive a minimum of four antenatal care visits (82%) and do not deliver at a facility (86%). In contrast, 39% of women in the richest quintile do not receive four antenatal care visits and 22% do not deliver at a facility.

- Each year in Ethiopia, 12,000 women die from complications of birth, abortion or miscarriage, and 92,000 newborns die in the first month of life. Most of these deaths could be prevented with adequate medical care.

- Of the 910,000 women and 1.4 million newborns who require care for medical complications related to pregnancy and delivery, only 15% receive the care they need.

- Despite Ethiopia’s notable gains in reducing unsafe abortion, of the 571,000 abortions occurring in 2018, 47% are estimated to take place outside of health facilities and are potentially unsafe.3,4

Health benefits of meeting women’s need for services

- If all unmet need for modern contraception in Ethiopia were satisfied, unintended pregnancies would drop by 90%, from 2.1 million to 219,000 per year. As a result, the annual number of unplanned births would decrease from 1.2 million to 128,000 and the number of abortions would drop from 571,000 to 59,000.

- If full provision of modern contraception were combined with adequate care for all pregnant women and their newborns, maternal deaths would drop by 81% (from 12,000 to 2,000 per year) and newborn deaths would drop by 85% (from 92,000 to 13,000 per year).

Cost of contraception and maternal and newborn care

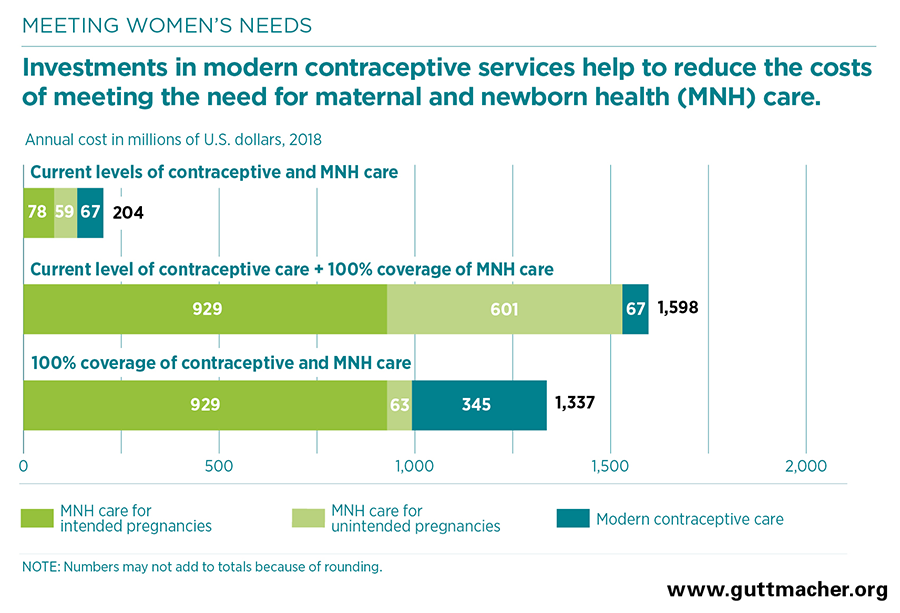

- The 2018 estimated annual cost of providing contraceptive services to the 7.2 million women of reproductive age in Ethiopia who currently use modern contraceptives is US$67 million. This includes direct service costs for drugs, supplies and personnel, as well as estimated indirect (program and health systems) costs.

- Meeting the need for modern contraception among all women in Ethiopia who want to prevent a pregnancy would cost $345 million annually, an increase of $278 million over current costs.

- In the scenario in which all unmet need for modern contraception among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia is met (assuming new users would adopt the same mix of modern methods used in 2018), costs would be $64 million for short-acting methods and $281 million for long-acting or permanent methods.

- Maternal and newborn care at current levels costs $137 million annually—$78 million for care related to intended pregnancies and $59 million for care related to unintended pregnancies. Fully meeting the current need for maternal and newborn care without increasing contraceptive use would cost $1.5 billion annually. However, if the full need for both contraception and maternal and newborn health care were met, the cost of maternal and newborn care would be reduced to $992 million.

- Because the cost of preventing an unintended pregnancy through use of modern contraception is far lower than the cost of providing care for an unintended pregnancy, for each additional dollar spent on contraceptive services above the current level, the cost of maternal and newborn health care would drop by $1.94.

- Fully meeting women’s needs for both contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care in Ethiopia would cost $1.3 billion annually ($12.81 per capita)—a total that is less than the cost of meeting the need for maternal and newborn care alone.

Recommendations

- Invest in meeting the need for modern contraceptive services and maternal and newborn health care to improve health outcomes. Investing in both sets of services is more cost-effective than focusing on maternal and newborn health alone. In addition, it has enormous benefits for women, families and society, and it would likely contribute to Ethiopia’s progress toward achieving goals set at the national, regional and global levels.

- Improve access to and provision of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care services, especially for vulnerable groups, such as pastoral communities.5,6

- Use routine training and mentorship to strengthen Health Extension Workers’ ability to provide contraception and maternal and newborn health information and services, including safe abortion care.7

- Implement health worker trainings focused on ensuring the provision of high-quality and respectful sexual and reproductive and maternal and newborn health services in the community and at health facilities.8