Sexually active women in developing countries who have an unmet need for contraception, meaning they wish to avoid pregnancy but are not using any contraceptive (traditional or modern), generally cite one of several key reasons for not using a method. Addressing their reasons for nonuse should inform family planning programs’ efforts to satisfy this need.

Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries: Examining Women’s Reasons for Not Using a Method

Author(s)

Gilda Sedgh, Lori S. Ashford and Rubina HussainReproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

Key Points

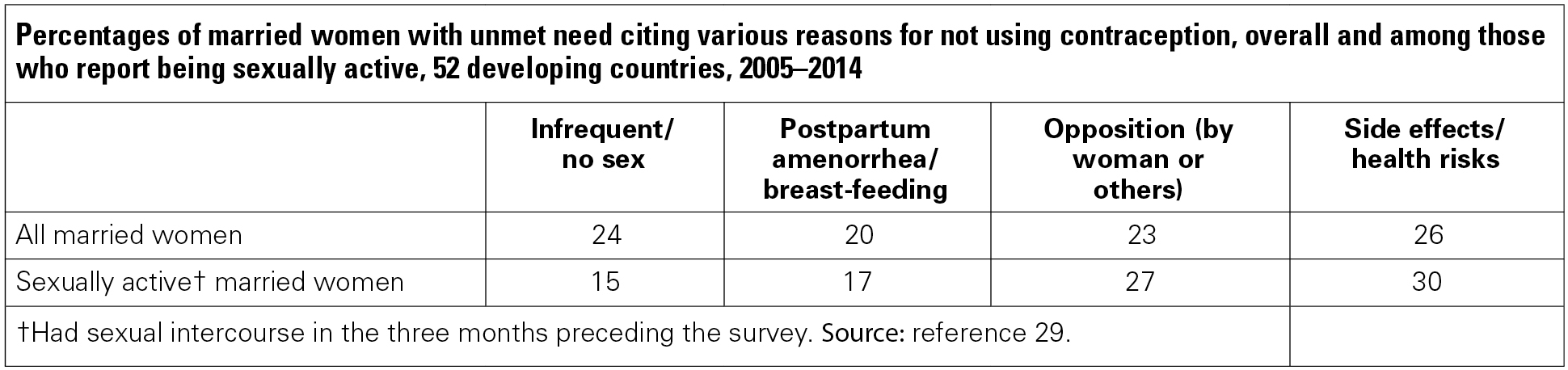

- Demographic and Health Surveys in 52 countries between 2005 and 2014 reveal the most common reasons that married women cite for not using contraception despite wanting to avoid a pregnancy. Twenty-six percent of these women cite concerns about contraceptive side effects and health risks; 24% say that they have sex infrequently or not at all; 23% say that they or others close to them oppose contraception; and 20% report that they are breast-feeding and/or haven’t resumed menstruation after a birth.

- In the majority of countries, married women who cite concerns about contraceptive side effects and health risks are more likely to have used a method in the past than are women who cite other reasons for nonuse.

- Married women who cite infrequent sex as a reason for nonuse are less likely to have had sexual intercourse in the three months preceding the survey than peers who cite other reasons for nonuse.

- Married women who cite opposition to family planning are less likely to have ever used any method than women who cite other reasons for nonuse. Thus, some, but not all, women might experience opposition that precludes trying a method at all.

- Among sexually active never-married women wanting to avoid pregnancy, the most common reason cited for not using contraception is infrequent sex (49%), followed by not being married (29%) and concerns about contraceptive side effects (19%).

- Women with unmet need for contraception rarely say that they are unaware of contraception, that they do not have access to a source of supply, or that it costs too much. The countries where more than 10% of women cite any of these reasons are in West and Middle Africa.

- Compared with earlier studies on women’s reasons for not using contraception, larger proportions of women now cite side effects and infrequent sex as reasons for nonuse.

- Contraceptive services should place priority on improving the information and counseling they provide and the range of methods they offer. All sexually active women, whether married or not, need information about their risk of becoming pregnant and about the choices of methods that could meet their needs.

Context and Purpose of the Report

For decades, information about unmet need for contraception has enabled health advocates and professionals, policymakers and funding agencies to identify the investments needed in family planning programs in developing countries. Generally speaking, women are considered to have an unmet need if they are sexually active and want to avoid becoming pregnant but are not using contraception. By helping women prevent unintended pregnancies, programs can reduce unwanted births and unsafe abortions, and improve maternal and child health.1,2 These gains can also contribute to other development objectives, such as curbing poverty and slowing population growth.3,4

Enabling women to act on their pregnancy preferences has become a high priority on the global development agenda. Recent initiatives have called for satisfying the unmet need for modern contraception, which arises when women want to avoid a pregnancy but are using no method or a traditional one. The most prominent of these initiatives is Family Planning 2020, a global partnership launched in 2012 that aims to add 120 million new users of modern contraceptives in the world’s 69 poorest countries by 2020.5

As of 2014, an estimated 225 million women in developing regions had an unmet need for modern contraception.2 (Of this total, 160 million were using no method and 65 million were using a traditional method.) The total changed little over the past decade, mainly because increases in contraceptive use have barely kept up with growing populations and rising desire for smaller families. The health implications of such a large unmet need are profound. Every year, an estimated 74 million unintended pregnancies occur in developing regions, the great majority of which are among women using no contraception or a traditional method. If all unmet need for modern methods were met, 52 million of these unintended pregnancies could be averted, thereby preventing the deaths of 70,000 women from pregnancy-related causes.2

Satisfying women’s unmet need for contraception requires identifying populations where such need is high, increasing or failing to decline. It also requires understanding why women with an unmet need are not using a method, so that programs and services can respond effectively. What are the specific reasons women cite? How do these reasons vary across countries and regions? And how have the reasons cited changed over time?

Using the DHS to Explore Women’s Preferences

This report uses data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) to answer these questions. Since 1984, the DHS program has worked with developing-country governments to conduct household surveys of women of reproductive age in more than 90 countries.6 The survey program focuses on fertility; family planning; reproductive, maternal and child health; and related topics. It has pioneered efforts to define and measure unmet need for family planning.

Unmet need is a complex measure, discussed in greater detail in the next section. Demographers and public health experts have debated over the years how it should be defined and what it reveals about women’s intentions and motivations.7 The DHS does not ask women directly whether they need contraception. Rather, it infers need based on a woman’s current sexual and reproductive status (sexual activity, fecundity, pregnancy and contraceptive use) and whether she wishes to have a child (or another child) soon or ever.

We examine the reasons why women do not use contraception despite wanting to avoid a pregnancy. The surveys ask this question only of women using no method at all, not of those using traditional methods. Hence, the analysis of unmet need in this report is limited to women not using any contraceptive method.

In addition, we use the DHS data to explore some of the behaviors and experiences of women who give particular reasons for not using a method. For example, we look at whether they report being sexually active recently and whether they have previously used contraception. These results provide additional insight on whether women’s reasons for nonuse are amenable to intervention.

We present results for married women and for sexually active never-married women where such information is available. In the survey program’s early years, only ever-married women were asked questions related to unmet need because sexuality and reproduction were deemed sensitive topics.8 Over time, however, as women in the developing world have increasingly delayed marriage, and as sexual activity among single women has concurrently increased,9 so has the importance of collecting data from unmarried women. This report examines 31 countries with at least one DHS in the last decade that collected information about the reasons for contraceptive nonuse among sexually active never-married women.

Prior Analysis of Reasons for Nonuse

A Guttmacher review of DHS surveys from 1995 to 2005 showed that women’s lack of knowledge about contraception had declined substantially compared with that in the 1980s, and that concerns about the side effects and health risks associated with modern contraceptive methods had become increasingly common throughout the developing world.10 Women commonly cited infrequent sexual activity and breast-feeding as reasons for not using contraception, which could have been interpreted to indicate that many believed they had a low risk of becoming pregnant.

High levels of unmet need are sometimes interpreted as evidence of a lack of access to contraceptive supplies and services in developing countries. This interpretation is oversimplified, however. Even in 1995–2005, women rarely cited a lack of access or cost as a reason for not using a method, and some with unmet need said they did not intend to use contraception in the future.10–13 DHS data have been useful in revealing the reasons why women might not seek contraceptive services, irrespective of ease of access or cost. However, because the reasons for nonuse are based on only a single question, the responses do not necessarily capture the potentially complex interplay of barriers that contribute to nonuse.

Qualitative studies have also examined barriers to contraceptive use, uncovering issues similar to those found in the DHS, but with more explanatory detail. Although these studies have been limited to small geographic areas, some key themes have emerged. For example, a review of studies of young women, primarily unmarried women in Sub-Saharan Africa, identified a lack of family planning education and information regarding how contraceptive methods work as underlying themes.14 The review found that young women were concerned about side effects and health risks, such as menstrual disruption and infertility, and unmarried women were also unwilling to risk the social disapproval associated with seeking services. Studies that explored why women stopped using their methods have also revealed the importance of health concerns and side effects, such as changes in bleeding patterns, weight gain and headaches, in women’s decision making about methods.15–17 Other studies have shown that men as well as women have concerns, real or imagined, about the effects of contraceptive methods on women’s bodies—their weight, menstrual cycles, libido, sexual desirability and pleasure.18–20 Moreover, such studies reveal that both men’s and women’s opposition to family planning could be related to traditional gender norms or to a suspicion that outsiders (Westerners) aim to control women’s fertility.19,21

Scope of This Report

To provide background and context, we start this report by describing women’s desire for children, contraceptive use and levels of unmet need in 52 countries that had surveys between 2005 and 2014 and for which data were available at the time of this analysis. We then focus on the reasons women give for not using contraceptives despite wanting to avoid a pregnancy.

We provide data for both married and sexually active never-married women, and also highlight the situation of young women aged 15–24, married and not. This group has been the focus of numerous international initiatives to improve reproductive health, as detailed in a later section. We also discuss trends in the proportions of married women giving specific reasons for nonuse, by examining countries that have had multiple surveys since 2000 with comparable data on reasons for nonuse.

Through these analyses, this report can inform policymakers, program managers and donor agencies on how programs can respond most effectively to meet women’s contraceptive needs. The implications of the report’s findings and recommendations are outlined in the last section. The appendix contains supplemental tables on specific groups of women with unmet need and trend data on women’s reasons for not using a method.

Data and Methods

Data Sources

The findings presented in this report are based primarily on data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in 52 countries between 2005 and 2014. Forty of the surveys were conducted between 2010 and 2014. Data from earlier survey years are also shown for comparative purposes. The DHS collects information from nationally representative samples of women of reproductive age (15–49 years old) on fertility; family planning; reproductive, maternal and child health; and other health issues. In all countries, the surveys use a standardized, core questionnaire, which the DHS program has developed and refined over the past three decades.

Other global reviews have assessed unmet need for family planning based on a wider range of surveys, including the Reproductive Health Surveys conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys conducted by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and surveys from the Pan Arab Project for Family Health.2,22,23 Our analysis is limited to countries with DHS data because these data include consistent and comparable information about why women with unmet need are not using a contraceptive method.

Of the 52 countries included in this report, 32 are in Africa, 13 are in Asia and seven are in Latin America and the Caribbean,* following the regional classifications of the United Nations Population Division. The number of women aged 15–49 interviewed in the most recent surveys ranged from 2,615 in Sao Tome & Principe to 124,385 in India. The populations of women surveyed in the 52 countries account for 66% of all women of reproductive age in the developing regions of the world excluding China.

Key Variables

Unmet need for contraception

We use the definition of unmet need for contraception commonly presented in DHS reports and revised in 2012 to ensure greater consistency in estimation across countries and over time.24 According to this definition, a woman of reproductive age (15–49) has unmet need if

- she is married (legally married, cohabiting or in a consensual union) or unmarried and sexually active;

- she is not using any method of contraception, either modern or traditional;

- she is fecund; and

- she does not want to have a child (or another child) in the next two years or at all.

In addition, women who are pregnant, or who are experiencing postpartum amenorrhea (have not resumed menstruation after a birth in the two years preceding the survey), are classified as having unmet need if they indicated that their current or recent pregnancy was unintended. Even though they do not have an immediate need for contraception, these women are included because they previously had an unmet need or a method failure, and might want to avoid another pregnancy when they are fecund again.

The DHS definition considers a woman infecund (and therefore having no need for contraception) if she meets any of three criteria:

- she was married for at least five years before the survey and did not use contraception, did not have a birth during that time and was not pregnant at the time of the survey (note: some of these women might have had abortions, so the indicator could overstate infecundity);

- she has not had a period for at least six months and is not pregnant or experiencing postpartum amenorrhea; or

- she indicated in response to questions about fertility intentions or reasons for not using contraception that she is menopausal, has had a hysterectomy or otherwise cannot get pregnant.

The DHS uses an algorithm for determining unmet need that draws from 15 survey questions.24 First, women are categorized according to whether or not they are using a contraceptive method. Among nonusers, women who are pregnant or have postpartum amenorrhea are classified as having unmet need if their current or recent pregnancy was unintended. Women who are not pregnant or experiencing postpartum amenorrhea are further classified according to whether they are fecund; fecund women who want to avoid a pregnancy for at least two years are classified as having an unmet need. Finally, women with unmet need are grouped according to whether they have unmet need for spacing births (delaying a first birth or postponing higher-order births) or limiting births (stopping childbearing altogether).

Because a key objective of measuring unmet need is to identify women at risk for unintended pregnancy, some reports focus on levels of unmet need for modern contraception,2,25 which classifies women using traditional methods (such as withdrawal and periodic abstinence) as having unmet need. These women face a greater risk of unintended pregnancy than peers using modern methods because traditional methods have comparatively higher failure rates.26 This report, however, looks at women having unmet need for any method—that is, those using neither a traditional nor a modern method—because these women are asked to give a reason for nonuse. Women who use traditional methods are not asked why they are not using a modern one.

As other studies have done, we look at unmet need for contraception both to space births and to limit births, which can help identify the proportions of women in need of temporary, long-term or permanent methods. In addition, our analysis includes a third category: unmet need for postponing motherhood among women who have yet to start childbearing. Our approach therefore differs from that of other studies that classify this need as part of unmet need for spacing births.22 The tendency to begin contraceptive use only after a first child is born is widespread throughout the developing world, especially in cultures where women are expected to have a child soon after marriage. Delaying childbearing can enable women to complete their educations, earn income or both. Thus, having a separate indicator denoting the need to delay a first birth helps gauge the extent to which young women who want to postpone starting a family are able to do so.

Estimates for married and unmarried women

For the purpose of measuring the need for contraception, all married women are considered sexually active, as are unmarried women who report recent sexual activity. Prior research has shown, however, that many married women cite infrequent sex as a reason for not using contraception. Thus, we present data for all married women in the main text and examine separately only those married women who reported being sexually active.

For both married and unmarried women, we define sexually active as having had sexual intercourse in the three months (93 days) preceding the survey interview. Some studies of unmarried women have used the DHS standard definition of sexually active as having had sex in the past month.7,24,27 Others have used the three-month time frame.2,22,25 We use the latter, broader measure to capture realistic variations in the frequency of sexual relations among married women and the sporadic nature of unmarried women’s relationships. This time frame also yields larger sample sizes and thus more robust results.

Unmarried women face challenges related to contraceptive use that differ from those of married women, and their needs are sometimes harder to determine. Strong taboos against sexual activity outside of marriage make it more difficult to collect and assess unmet need data: Surveys do not always ask unmarried women about recent sexual activity, and even when they do, the women may underreport their sexual activity and contraceptive use.11,28 Yet, it is important to know why sexually active unmarried women are not using contraception, because they make up an estimated 18% of all women with unmet need for any method in developing countries.25 The potential social, economic and health-related consequences of unintended pregnancy for unmarried women make it essential to measure and understand their unmet need for contraception.

Some analyses of unmet need among unmarried women have combined women who have never married with formerly married women—those who are separated, divorced or widowed. In this analysis, however, we exclude formerly married women because, in many countries, there are too few of them to examine on their own, and because preliminary analyses indicated that their reasons for unmet need often differ from those of never-married women. Also, reproductive health professionals are particularly concerned about the risks and consequences of unintended pregnancy for never-married women, who are predominantly young. In developing regions, the vast majority of never-married women are aged 15–24.

Thirty-one of the 52 countries have information about reasons for nonuse of contraception among sexually active never-married women. The remaining 21 countries—12 in Asia and nine in Africa—have insufficient information, either because never-married women were excluded from the DHS, or because the size of the sample of sexually active never-married women is too small to produce reliable estimates of unmet need.

Reasons for not using contraception

In the DHS, women who are not using any method of contraception, and who say that they do not want to have a child in the near future, are asked to indicate their reasons for not using a method. The question takes this general form: "You have said that you do not want a child soon/another child soon/any more children, but you are not using any method to avoid pregnancy. Can you tell me why?" The questionnaire also follows up with "Any other reason?" but offers no specific prompts.

To help interviewers code the women’s responses, DHS questionnaires include a list of more than 20 precoded answers, and they also allow interviewers to enter women’s other, uncoded reasons. Because women with unmet need are allowed to provide more than one reason for not using a method, the proportions citing various reasons may add to more than 100%. In this analysis, we categorize women's responses according to whether they relate to

- sexual activity or fecundity (a woman reports infrequent or no sex, or believes she is unable to get pregnant);

- postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both;

- opposition to family planning by the woman herself or someone close to her;

- awareness and access issues, including awareness of methods and their availability and cost, and access to a source; and/or

- issues pertaining to method use, including side effects, health risks and inconvenience.

The pool of women defined to have unmet need and those who are asked reasons for not using contraception are not identical. For example, women with unmet need who are pregnant, or who say they are not sure whether or when they want to have a child, are not asked about their reasons for not using contraception.† Therefore, we are examining reasons given by a large subset of women with unmet need, rather than all of them. The women’s responses shed light on the reasons behind the seeming contradiction of needing contraception and yet not using it, and therefore are presented to deepen our understanding of unmet need.

Analytic Approach

We present the proportions of women with unmet need for contraception in each country and the percentage distributions of women according to whether they have an unmet need to postpone a first birth or to space or limit higher-order births. The DHS program uses sampling weights for women in each survey to correct for differential representation of some demographic groups and to render more nationally representative samples. The tables in this report give weighted results along with the unweighted sample size (n) for each variable. Married and never-married women are shown separately.

Next, we present proportions of women with unmet need in various population subgroups, defined by social and demographic characteristics: age-group (in five-year increments), residence (urban versus rural), wealth (poor versus nonpoor)‡ and education (less than seven years versus more). We show findings of chi-square analyses performed to detect whether any variations in unmet need by subgroup rose to the level of statistical significance.§

To examine more closely the experiences of women who gave specific reasons for nonuse, we present the following:

- the proportion of women who had sex in the past three months and past month, among those citing infrequent or no sex as their reason for nonuse;

- the proportion of women who gave birth in the past six months, among women citing postpartum amenorrhea or breast-feeding; and

- the proportion of women who had ever used any contraceptive method—among those citing concerns about side effects and health risks, among those citing opposition to contraception, and among those citing access issues. (Ever-use of a modern method was not available across all surveys.)

We present data for three major UN regions: Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional averages are shown where the combined populations of women aged 15–49 in the surveyed countries accounts for 50% or more of the region’s population of women that age.

The regional averages are not weighted for population size, although such weights are often used to give a sense of the numbers of women citing each reason. In the analysis presented here, small countries carry the same weight as large countries; therefore, the reasons expressed by women in small countries are not "lost" in the averages. The regional averages are thus more likely to reflect a typical country than the women of the largest country in a region.

We examine trends in reasons for nonuse of contraception for 39 countries having more than one survey between 1994 and 2014. Because of the variability in survey years, we do not aggregate trends at the regional level. For comparability, data from all survey years use the 2012 definition of unmet need.

Data Considerations

Readers should bear in mind several considerations when reviewing the data presented in this report. First, our analysis of the reasons for nonuse of contraception follows the categories established and reported by the DHS. Some of the reasons listed would benefit from more in-depth investigation. Second, although women are allowed to indicate multiple reasons for nonuse, most women stop after giving one reason, which could result in underreporting of some barriers to using contraceptives.

Third, the survey data provide a snapshot of all women’s exposure to pregnancy and contraceptive needs at one point in time—at a population level. The data are not meant to predict how any individual woman’s sexual behavior or needs might change over time. A particular woman might move in and out of the categories studied (i.e., a user or nonuser of contraception; sexually active or not; wanting a pregnancy or not).

Fourth, the number and population size of the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are too small to make generalizations about the whole region. Where this region is mentioned in the report, we refer to only seven countries with survey data from 2004 to 2014. Finally, the sample sizes of sexually active never-married women citing reasons for nonuse are much smaller than those of married women; therefore, the results pertaining to never-married women should be viewed with more caution. We omit from the tables values based on responses from fewer than 50 never-married women, but some findings shown are based on fewer than 100 women.

Levels of Contraceptive Use and Unmet Need

Rising levels of contraceptive use in developing countries have played a major role in enabling couples to have smaller families than in previous generations, and in improving women’s and children’s health. Still, nearly everywhere in the developing world, women’s childbearing experiences differ from their intentions.

Survey data on women’s ideal family size compared with the mean number of lifetime births per woman (the total fertility rate) reveal that on average, women have more children than they prefer to have (Table 1). Outside of Central Asia, where the gap between desired and actual fertility is negligible, women have between 0.5 and 2.2 more children than they intend to have.29

The incidence of unplanned births—which includes both mistimed births (wanted, but at a later time) and unwanted births—also provides evidence that women face obstacles to controlling their fertility. Unplanned births range from 3% of all births in the Kyrgyz Republic to 60% in Bolivia. Unplanned births tell only part of the story, however; levels of unintended pregnancy are higher in all countries, to varying degrees, because some pregnancies end in abortion.30 If all women who wanted to avoid a pregnancy were to use a modern contraceptive method, abortions as well as unplanned births would drop dramatically.2 Reducing unmet need is also an important strategy to lower fertility rates in countries with rapid population growth.

To set the stage for exploring the reasons underlying unmet need, this section and Tables 1–5 present levels of contraceptive use and unmet need in the 52 countries studied, along with some of the background characteristics of these women. Married women are presented separately from sexually active never-married women.

Contraceptive Use Among Married Women

The proportion of married women aged 15–49 using contraception varies widely in the countries included in this analysis. Table 1 shows the proportions who have ever used a contraceptive method (traditional or modern), are currently using any method, and are currently using a modern method. Generally speaking, the majority of married women in Latin American and the Caribbean and in Asia currently use contraception, and most of these users rely on a modern method (Figure 1), except in a few countries in Central Asia. In contrast, in Africa, the majority of married women are not using contraception, with the exception of Swaziland, Rwanda, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Egypt, where 51–59% of married women are using a method.

The proportion of married women who rely on traditional methods varies widely, from 0–1% of users in many countries to 37% in Azerbaijan. Still, in the majority of countries (41 out of 52), fewer than 10% rely on such methods.

Unmet Need Among Married Women

Overall patterns of unmet need

For the most part, unmet need for contraception is inversely related to contraceptive use, although women’s desire for children also factors into the equation. In the 52 countries studied, the proportion of married women aged 15–49 with an unmet need for a method of contraception (either modern or traditional) ranges from 8% in Colombia to 38% in Sao Tome & Principe (Table 2). Unmet need is highest in countries such as Haiti, Ghana and Uganda, where the use of contraception is still very low. In 24 countries, at least a quarter of married women have unmet need; 20 of these countries are in Africa. At the other end of the spectrum, the five countries with the lowest levels of unmet need—Colombia, Peru, Honduras, Dominican Republic and Indonesia—have the highest levels of contraceptive use. A few countries, such as Niger and Nigeria, have relatively low unmet need along with low contraceptive use because the desired family size is still relatively high.

Married women who are fecund and want to avoid a pregnancy are classified as having a need for contraception: That need is considered to be met for those who are using contraception (modern or traditional in this analysis) and unmet for the rest. Figure 2 shows the distribution of married women according to whether they have an unmet need, a met need or no need for contraception. Married women with no need include those who are infecund, pregnant with an intended pregnancy, or postpartum amenorrheic after an intended pregnancy, or would like to have a birth in the next two years. Overall, the proportion of women with "no need" is higher in Africa than in the other two regions because fertility is much higher in Africa—that is, women spend more time pregnant, postpartum amenorrheic or wanting to become pregnant. As couples increasingly desire smaller families and as contraceptive use rises, the size of this group of women will decline.

Women with an unmet need for contraception may wish to delay, space or limit their births (Figure 3). Among married women, unmet need to delay a first birth is relatively rare. It is 2% or less in nearly all of the 52 countries; the only exceptions are Haiti, Nepal and Comoros, where 3–4% of married women have an unmet need to postpone a first birth. This largely reflects the fact that in developing countries, women often want, or are expected to have, a child soon after marriage. The relative importance of spacing versus limiting varies across countries; still, as a general rule, those with higher fertility, such as in Sub-Saharan Africa, have higher proportions of women with unmet need for spacing births compared with those with lower fertility.

These data have implications for the types of methods that women might prefer to adopt. For example, if the majority of women who need contraceptives would like to have a child in the future, then programs focusing mainly on sterilization would not be appropriate, and some women might be reluctant to use IUDs and implants in settings where removal could be difficult. Offering effective short-term methods, such as pills and injectables, or backup methods, such as emergency contraception, along with the former could be more acceptable and appropriate.

Unmet need among subgroups of married women

Married women across all age-groups have an unmet need for contraception (Table 3 and Figure 4). In the Latin American and the Caribbean countries with surveys, unmet need is highest among women aged 15–19, and it declines for each subsequent five-year age-group. (Regional averages are not shown for Latin America because the data represent too few countries in the region.) In Asia, unmet need is highest among the youngest age-groups. This pattern might reflect that women in this region commonly rely on sterilization once they have their desired number of children. In Africa, unmet need is roughly equally high across all age-groups except for women aged 45–49, who have the lowest level. But patterns in individual countries vary a great deal. In Egypt and Indonesia, unmet need is lowest among married women aged 15–19 and increases in each subsequent age-group. By contrast, in Burkina Faso, Burundi, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Swaziland and Tanzania, unmet need is highest among women 35–39 or 40–49 years old—groups who most likely have reached their desired family size.

Levels of unmet need are generally higher in rural areas than in urban areas, but in many countries, the rural-urban divide is narrow (Table 3). Bolivia, Comoros, Ethiopia, Lesotho and Uganda have wide rural-urban gaps of 10 percentage points or more (with higher unmet need in rural areas). On the other hand, Sao Tome & Principe is the only country with unmet need that is 10 percentage points higher in urban areas compared with rural ones.

Differences in levels of unmet need are somewhat more pronounced between poor and better-off women, and between less and more educated women. In nearly all countries, women who are poor (in the bottom two wealth quintiles) experience greater unmet need than those who are nonpoor (in the other quintiles). Also as expected, married women with fewer than seven years of education generally have higher levels of unmet need than counterparts with more years of schooling. Across all regions, the only countries in which levels of unmet need are at least five percentage points higher among more educated women are Armenia and Nepal.

Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use Among Never-Married Women

A total of 31 countries—23 in Sub-Saharan Africa, seven in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one in Asia (Philippines)—have sufficient data on never-married women to analyze unmet need. In most of these countries, between 10% and 40% of never-married women are sexually active, defined as having had sex in the past three months (Table 4 and Figure 5). The proportions of never-married women who have had a child range widely, from 5% in the Philippines to 51% in Namibia. In most countries, the majority of births among never-married women are unplanned.

In six countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and in the Philippines, a smaller proportion of sexually active never-married women currently use contraception compared with married women (Tables 1 and 4). Africa presents a different picture, however: In 23 of the 26 countries with data, sexually active never-married women are more likely to use contraception than their married counterparts.

Unmet Need Among Never-Married Women

Sexually active never-married women are a much smaller population than married women in the developing countries included in this analysis, because most women marry, and social norms often discourage sexual activity before marriage. However, this group has a comparatively higher level of unmet need for contraception overall (Table 2). As shown in Figure 6, between 17% and 59% of sexually active never-married women—in Congo and Haiti, respectively—have an unmet need.

Never-married women generally account for fewer than half of all women with unmet need in most of the countries with data, from 3% in Comoros and Ethiopia up to 51% in Namibia (Appendix Table 1). But because these women experience greater unmet need than do their married peers, their share of unmet need is disproportionate to their population size. Moreover, their levels of unmet need could be even higher than shown in the survey results because never-married women in conservative societies may be reluctant to admit being sexually active.

In contrast with married women, the vast majority of never-married women have an unmet need to delay their first birth (Figure 7), reflecting that they are predominantly young and plan to have a child in the future. An exception can be seen in Swaziland, where more of the never-married women with unmet need report wanting to limit births (14%)—that is, to stop having children—than to delay or space births.

In nearly every country with available data, the youngest age-group of never-married women, those aged 15–19, have the highest unmet need (Table 5), reflecting the challenge of being young and single and in need of contraception. As noted for married women, and almost without exception, unmet need is higher among the never-married women who live in rural areas, are from poorer households and have fewer than seven years of education.

Reasons Women Cite for Not Using Contraception

The reasons why women do not use contraception despite wanting to avoid a pregnancy can inform policies and programs to reduce unmet need and the incidence of unwanted pregnancy. The information can be used in the design of behavior change campaigns and sexuality education; in the development and introduction of new contraceptive methods; and in provider training and service delivery, including counseling about methods.

Reasons for Nonuse Among Married Women

The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) asks women who want to avoid a pregnancy in the next two years to indicate all of their reasons for not using contraception. In the surveys of married women included in our analysis, most gave only one reason for nonuse; the average number of reasons per respondent was 1.2. Thus, the proportions of women citing various reasons may add to slightly more than 100%.

Overview of reasons

Among married women with unmet need in all regions, the four most common reasons women cite for not using contraception are that they have sex infrequently or not at all; that they have concerns about the side effects, health risks or inconvenience of methods; that they have not resumed menstruation after a birth, are breast-feeding or both; and that they or someone close to them opposes family planning (Table 6 and Figure 8). Relatively few women say that they are unaware of methods; that the cost is too high; that they lack access to contraception; or that they are not fecund. The prevalence of each reason differs greatly among individual countries and varies somewhat between the Africa and Asia regions (Figure 9). The regional average for Latin America and the Caribbean is not shown because data are available for too few countries in that region.

Sexual activity and fecundity

A major reason for nonuse among married women with unmet need pertains to women’s perceptions about the risk of pregnancy. Women may believe they have little or no risk of conceiving if they have sex infrequently or not at all; they are experiencing postpartum amenorrhea (they have not resumed menstruation after giving birth), are breast-feeding or both; or they believe that they are infecund or subfecund.

Infrequent or no sexual activity. About one-third of married women with unmet need in Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean cite infrequent or no sex as a reason for not using contraception (Table 6). In Africa, about one-fifth of women cite this reason, on average. With regard to individual countries, the reason is especially prevalent in Nepal (where it is cited by 73% of women with unmet need), Bangladesh (57%) and Peru (53%—Figure 10). In 12 countries, infrequent or no sex is the most commonly cited reason for nonuse. The only countries in which this reason is rare (cited by fewer than 10% of those with unmet need) are Timor-Leste, Burundi and Ethiopia.

The prevalence of infrequent or no sex as a reason for nonuse is greater in countries with higher levels of contraceptive use (and lower unmet need)—presumably because other reasons have been resolved or are no longer relevant. Women citing this reason may perceive that they have sex too infrequently to warrant contraceptive use, or believe that contraceptive methods are too burdensome for the number of times they have intercourse. Alternatively, they may be having infrequent sex in order to avoid an unwanted pregnancy.16

We analyzed other responses of the women citing this reason to determine whether they are, in fact, having sex infrequently. The DHS questions on women’s sexual activity (and relationship status) are asked separately from the questions on reasons for not using contraception; thus, we can use responses to the former as a "check" on the latter.

Across the 52 countries, 23% of married women with unmet need, on average, report not being sexually active in the past three months, with a range of 4–55% in individual countries (Figure 11). These women have a low risk of becoming pregnant and therefore may be unlikely to seek contraceptive services. Among the married women who cite infrequent or no sex as a reason for nonuse, about half (47%) report being sexually active in the past three months, compared with 77% among all women with unmet need (Table 7). This finding is consistent with an earlier analysis showing that women who cite infrequent sex as a reason for nonuse are less likely to have been sexually active in the prior three months than all women with unmet need.31 Whether these women should be defined to have unmet need is discussed in Box 1.

Substantial proportions of married women who cite sexual inactivity as a reason for not using contraception also report that their husbands are away or staying elsewhere—46% overall, but with much variation by country: Proportions range from 16% in Tanzania to 79% in Haiti and Armenia and 87% in Nepal. Other countries where two-thirds or more of these women say their husbands are away include Dominican Republic, Bangladesh, Lesotho, Rwanda and Senegal—possibly reflecting high levels of men leaving home for work in these countries. Other women may be avoiding sexual activity instead of using a contraceptive method;11 these women could clearly benefit from improved services, including a range of contraceptive methods from which to choose.

Attention must also be paid to the women citing infrequent or no sex who are sexually active—from 22% of those with unmet need in Armenia to 79% in Cambodia. This group may be underestimating their risk of becoming pregnant. In fact, some of the women citing this reason were sexually active within one month preceding the survey—between 8% and 61% of women gave this response in Armenia and Cambodia, respectively. These women need better information and counseling about contraceptive methods that would be appropriate and effective in their situations.

Postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both. A woman who reports postpartum amenorrhea (lack of menstruation since her last birth) or breast-feeding as a reason for not using contraception may believe that her likelihood of becoming pregnant is minimal, or she could be afraid that a hormonal method will negatively affect her breast milk or her health. Alternately, her reasons could be cultural: In some societies, women are expected to abstain from sex during the postpartum period, and therefore, they might feel that contraceptive use is inappropriate.

On average, postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both are more commonly cited in Africa than in other regions (Table 6 and Figure 12). It was the most commonly cited reason in 12 countries—11 in Africa plus Kyrgyz Republic—and was cited by 20–49% of women in another 10 countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, high fertility and long durations of breast-feeding could explain this relatively high prevalence.

Many of these women’s perceptions about not needing contraception may be incorrect, however. According to the World Health Organization, the contraceptive benefits of lactation are limited to women who are exclusively breast-feeding, and they extend for six months after birth or the duration of postpartum amenorrhea, whichever is shorter.32 In more than half of countries in which women cited postpartum amenorrhea or breast-feeding as a reason for nonuse (and in all of the countries in Africa—Table 8), only a minority of women met the criteria for lactational amenorrhea as protection against pregnancy. In other words, the majority had given birth more than six months ago, had resumed menstruation or both, and were therefore potentially at risk for unintended pregnancy. In other words, unless these women are practicing postpartum abstinence, they may be underestimating their risk of becoming pregnant.

Subfecund and infecund. A small minority of married women with unmet need cite their inability to become pregnant as a reason for not using contraception (Table 6). In five countries—Colombia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Jordan and Pakistan—10% or more of women cited this reason; in all other countries, the proportions are in the single digits. The DHS does not include women who are permanently infecund—those who are menopausal or who have had a hysterectomy—among the group defined to have unmet need. Nevertheless, some women who are classified as fecund report that they are not using a method because they have difficulty becoming pregnant.

The women who say that they are unable to become pregnant may or may not be correct in their assessment; it is too small a population for further analysis. Although this particular reason does not appear to be a major factor in women’s contraceptive decision making, the combination of reasons that seem to reflect women’s perceptions that they are at low risk of pregnancy—whether because of infrequent sex, breast-feeding, postpartum amenorrhea or subfecundity—deserve greater attention and further research. Taken together, these perceptions represent one of the most important reasons for nonuse of contraceptives in developing regions.

Opposition to contraception

Opposition to contraception could reflect a woman’s personal beliefs or those of her partner or another person who influences her contraceptive decision making. The opposition could stem from conservative social values, religious or fatalistic beliefs, or concerns about certain attributes of various methods. In all three world regions, married women with unmet need are on average more likely to cite their own opposition to contraception than to cite someone else’s opposition (Table 6). Some women who cite personal opposition may also have partners who are opposed, even if they do not indicate it in the survey.

Opposition to contraception (by the woman or others) is the most commonly cited reason in 10 countries—all in Asia and Africa. The highest prevalence of this reason was found in Timor-Leste (68%), Pakistan (49%) and Tajikistan (45%—Figure 13). At the low end of the spectrum, only 4–8% of married women with unmet need cited opposition as a reason for nonuse in Colombia, Peru, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Nepal. These five countries have high contraceptive prevalence rates compared with others in their respective regions.

Prior contraceptive use among women who cite opposition ranges widely among the 48 countries with data on this question—from 4% in Burkina Faso to 82% in Colombia (Table 9) Compared with married women with unmet need who cite any reason for nonuse, those who cite opposition are less likely to have ever used a method in nearly all countries. Thus, although some women might be opposed because of prior experiences with methods, many seem to experience opposition that precludes trying a contraceptive method at all.

Lack of knowledge or access

Not knowing about contraceptive methods is rarely cited as a reason for nonuse in the surveys included in this study, the large majority of which were conducted in the last five years. In most countries, only 0–4% of married women with unmet need are unable to identify a contraceptive method; the proportion reaches 5% or more in eight countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Timor-Leste and Bolivia (Table 6). In Cameroon and Cote d’Ivoire, 10% and 12% of married women with unmet need, respectively, lack knowledge about contraception. It is not clear whether these women do not know about family planning, or whether they need to know more about specific methods before deciding to use one. It is possible that the women who have poor knowledge of contraception live in an environment with a low presence of family planning services.

In addition, fewer than 10% of married women with unmet need cite the high cost of contraception as their reason for not using a method in all countries except Benin, Burkina Faso, Comoros and Congo, where 10–15% of respondents cite this reason. The countries in Western Africa and Middle Africa where reasons related to knowledge, access and cost are still prevalent require greater efforts to expand the availability of low-cost contraceptive supplies and services.

Married women also rarely cite a lack of access as a reason for not using contraception. Such reasons could include not knowing a source, not being able to get to one (i.e., because of distance or a lack of transportation) or both. Fewer than 10% of married women with unmet need cite an access-related problem in all countries except Cameroon, Congo (DRC), Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea, where between 12% and 17% of respondents give this reason.

Collectively, these findings regarding awareness and access likely reflect the fact that family planning programs have existed for some time in most of the developing world, sources of supplies have expanded, and methods are offered at low cost or free of charge in public-sector health services. The findings do not necessarily show that access-related problems have been resolved, but suggest that women perceive other reasons for nonuse to be more important. It is also possible that access-related issues are underreported because most women cite only one reason for nonuse.

Side effects, health risks and inconvenience

In 21 of the 52 countries studied, side effects, health risks and inconvenience are the most commonly cited group of reasons given by married women with unmet need for not using contraception. (Among these reasons, inconvenience of methods accounts for only a small minority of responses.) In most countries, 20–33% of married women with unmet need report not using contraception because they are concerned about side effects and health risks associated with use. The proportion ranges from a low of 7% in Armenia to a high of 53% in Cambodia (Figure 14).

The similarity in responses across world regions suggests that these concerns are not necessarily grounded in local cultures and practices, and might have more to do with the methods themselves and women’s experiences with them.22,31 It is possible that some of the women have had side effects in the past; that they heard about side effects or health problems from others; or that they simply fear that the methods could be harmful. The DHS does not ask women which side effects or health risks they are concerned about in particular, but we know from qualitative studies that women have concerns about changes in bleeding patterns—a lack of menstruation or excessive bleeding—and that some are afraid the methods will make them sterile or cause other health problems.14

A previous analysis showed that women who express concerns about side effects and health risks associated with contraceptive use might base their rationale on prior experience using modern methods.31 The study found that in three-fourths of the countries where data were available on reasons for unmet need, women who cited side effects and health concerns were significantly more likely to have used a modern method in the past than were women who cited other reasons for nonuse. Additional research has shown that concerns about side effects and health risks are major reasons for discontinuing contraceptive use,33,34 and that these concerns are especially common among women who previously used injectables, IUDs and oral contraceptives.35

Table 10 shows the proportions of women citing side effects, health risks or inconvenience who have used any method of contraception in the past. Consistent with previous findings, in the majority of countries, the subset of women citing concerns about side effects have higher levels of prior use than do all married women with unmet need. Also, in general, women who cite concerns about health and side effects have higher levels of prior contraceptive use than women who cite opposition to contraception, shown in Table 9.

Reasons for Nonuse Among Sexually Active Never-Married Women

As with married women, the DHS asks sexually active never-married who want to avoid a pregnancy why they are not using a contraceptive method. Thirty-one countries have sufficient data on these women’s reasons for nonuse.

Overview of reasons

Never-married women with an unmet need for contraception give a range of reasons that are similar to those of married counterparts, except that many say that they are not using contraception because they are "not married" (Table 11). Other common reasons include infrequent sex, side effects/health risks and opposition to contraception. Knowledge, access and cost are the least common reasons, although 10% or more of never-married women cited one of these reasons in Congo, Congo (DRC), Namibia and Nigeria.

Infrequent or no sexual activity

Infrequent or no sex was the most common reason cited by never-married women with unmet need in six out of seven Latin American and Caribbean countries and in 10 out of 23 African countries. In Latin America and the Caribbean, 36–88% of never-married women with unmet need cited this reason, and in Africa, somewhat lower proportions did, 15–62% (Figure 15).

At first glance, this response seems to contradict these women’s status. By definition, all never-married women with unmet need had sex in the three months preceding the survey. To gain greater insight into this response, we looked at the proportion of women citing this reason who had been sexually active in the month preceding the survey. In all of the 21 countries with sufficient data on this question, most of these women had not had sex in the prior month—only 26% did on average; thus 74% last had sex 2–3 months before the survey (Table 12). Some of these women might be sexually active only sporadically, or their relationship status might be in transition. They would need services and methods that suit these circumstances. On the other hand, in 11 of the 21 countries, between 25% and 46% of women were sexually active in the prior month, indicating that a sizable share of women citing infrequent or no sex may underestimate their risk of becoming pregnant.

Not married

Never-married women who cite their nonmarried status as a reason for not using contraception might give this response because they are not having sex regularly; because they believe it would be socially unacceptable to seek contraceptive supplies and services before they are married; or because service providers deny some or all contraceptive methods to unmarried women. This reason is cited in all countries, with a prevalence ranging from 5% of never-married women with an unmet need in Liberia to 61% in Malawi (Figure 16). Not being married is the most frequently cited reason in the Philippines (51%) and eight countries in Africa.

We examined whether the never-married women citing "not married" as a reason for nonuse had sex in the prior month, and whether they previously used a contraceptive method (Table 13). Fifteen countries have sufficient data on these questions. Generally speaking, the majority of women citing this reason for nonuse reported that they had sex in the prior month, suggesting that "not married" does not mean infrequent sex but some other barrier to using contraception. The specific barrier is unclear, however. Prior use of contraception among women giving this reason ranges widely, from a low of 8% in Haiti to a high of 93% in Colombia, and it does not differ greatly from the levels of prior use among all never-married women with unmet need in these countries. Thus, among many women citing this reason, not being married did not prevent them from using a method in the past.

Subfecund or infecund

Fairly small proportions of never-married women with unmet need, between 1% and 22%, report they are not using contraception because they are subfecund or infecund (Table 11). This reason is most frequently cited in African countries, but it is not the most commonly cited reason for nonuse in any country. Women may give this response because they are experiencing postpartum amenorrhea or are breast-feeding, or possibly because they believe they are too young to be fecund. In any of these cases, the response reflects their belief that they are unlikely to become pregnant.

Opposition to contraception

Some never-married women with unmet need report that they or someone close to them opposes contraception. However, they cite this reason less often than do married women with unmet need. Given that never-married women are younger on the whole than married peers, the lower levels of opposition might reflect growing social acceptance of family planning. On the other hand, the "not married" response may be another way of signaling personal or social opposition to contraceptive use, thereby explaining the lower proportions of women who say outright that they are opposed. The proportions of never-married women who report that they or someone close to them opposes contraception ranges from 1% in Bolivia, Peru and Zambia to 37% in Haiti (Table 11 and Figure 17). It is the most frequently cited reason only in Haiti. In nearly all of the countries in which women cite opposition, more women say that they are opposed to contraception than say that their partners or others are opposed.

Side effects, health risks and inconvenience

Concern about side effects and health risks appears somewhat less common among sexually active never-married women than among married women. (As among married women, inconvenience is cited by a small share of never-married women in this category.) Across the countries where such data are available, the proportions vary widely, from 2% in Peru to 42% in Ghana (Figure 18). Concern about side effects is also high among married women in Ghana, and studies there have shown that many educated, urban women avoid hormonal methods.36 More research would be needed to investigate whether and how perceptions about side effects and health risks might differ between never-married and married women. The former can be expected to have had less experience with methods, and they may also perceive other barriers as more important than concerns about side effects. Very few countries have sufficient data on prior method use among never-married women who cite side effects as a reason for nonuse. Box 2 contains a discussion of reasons for nonuse among young women aged 15–24, whether married or not.

Box 1. Marriage as a Proxy for Sexual Activity

The unmet need definition classifies women who are currently married (in a legal or consensual union) as currently sexually active. It does not take into account married women’s responses to survey questions regarding recent sexual activity. Yet, past research has shown that some married women cite infrequent or no sex as reasons for not using contraception. Thus, in this study, we wanted to know how many of these women were, in fact, not having sex, and how removing this group might change our results.

When other researchers have removed women who had not had sex in the previous month from the pool of married women, the proportion with an unmet need for contraception fell by an average of 16%, with little variation by region, but a lot by individual country.7 In this analysis, we removed married women who had not had sex in the previous three months to see how levels of unmet need and reasons for not using contraception might change.

Impact of Excluding Sexually Inactive Women

In the 52 countries studied, between 3% and 38% of married women are not sexually active, defined as not having had sexual intercourse in the preceding three months (Table 1). If only the sexually active married women were included in the calculation of unmet need, the levels of unmet need would adjust downward slightly, by 1–3 percentage points in most countries (Table 2). In Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ghana, Lesotho and Sierra Leone, unmet need would drop by 4–5 percentage points, which represents a sizable proportion of all unmet need in those countries. In the most striking cases, Guinea and Nepal, unmet need would decline by 7–8 percentage points, representing a 28% and 30% drop, respectively.

Next, we looked at how the reasons for nonuse would change if the sexually inactive married women were excluded (see table below and Appendix Table 8). These data can help programs focus on the barriers to be overcome for the women who are most in need of contraceptives. Not surprisingly, the proportions of women citing infrequent or no sex would drop in nearly every country. Infrequent sex would still represent one of the top four reasons for not using contraception, but it would fall to fourth place. These are women who have had sex at some time in the past three months, but who perhaps do not perceive they have sex often enough to warrant contraceptive use.

The proportion of married women citing postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both as a reason for nonuse would also decline slightly in Africa and in Latin America and the Caribbean (but not Asia) if sexually inactive women were excluded. As noted previously, this response often reflects cultural preferences for abstaining from sex during the postpartum period. The women who are sexually active postpartum may be unaware of their risk of a subsequent pregnancy and therefore require better information and postpartum family planning services.

Both opposition to contraception and side effects/health risks become more important reasons for nonuse when sexually inactive women are excluded. The percentage of sexually active married women stating that they or someone else is opposed to family planning ranges from 5% in Indonesia to 68% in Timor-Leste (Appendix Table 8). In addition, the proportion citing concerns about side effects, health risks or inconvenience ranges from 9% in Mozambique to 56% in Cambodia.

Adjusting Future Estimates of Unmet Need

Unmet need would ideally refer to all sexually active women of reproductive age who want to avoid a pregnancy, whether or not they are married. The data presented here make clear that marriage is a reasonable but imperfect proxy for sexual activity. Refining the measure to capture the group of women of greatest concern would improve its usefulness in monitoring progress toward reducing unintended pregnancies.

Such a refinement would mean excluding sexually inactive married women from the standard measure of unmet need. However, it would also be necessary to collect information from unmarried women who are sexually active, which is currently not feasible in many developing countries. Even in countries where such data are collected, never-married women may underreport sexual activity and contraceptive use because of social and cultural taboos surrounding premarital sex, although there are scant empirical data to confirm this expectation. Adjusting the estimates for married women without adjusting them for unmarried women could result in underestimates of unmet need regionally and worldwide. Although these changes may not be feasible in the near future, they could remain part of longer-term efforts to refine the measurement.

Box 2. Young Women With Unmet Need and Their Reasons for Nonuse

Adolescent and young adult women (those younger than age 25) are of particular concern to reproductive health researchers and program planners because they are just beginning their reproductive lives and laying the foundation for their future. Helping these women avoid unintended pregnancies can have far-reaching benefits for the women, their future children and societies as a whole. By postponing childbirth, young women can finish their education, seek employment and have a birth at the healthiest times of their lives.

Numerous studies have detailed the social, cultural and economic barriers that young women face in obtaining and using contraceptives.8,41 For example, young married women may feel social pressure to have a birth soon after getting married,42 and single sexually active women may believe that using a method would call attention to their socially stigmatized behavior.

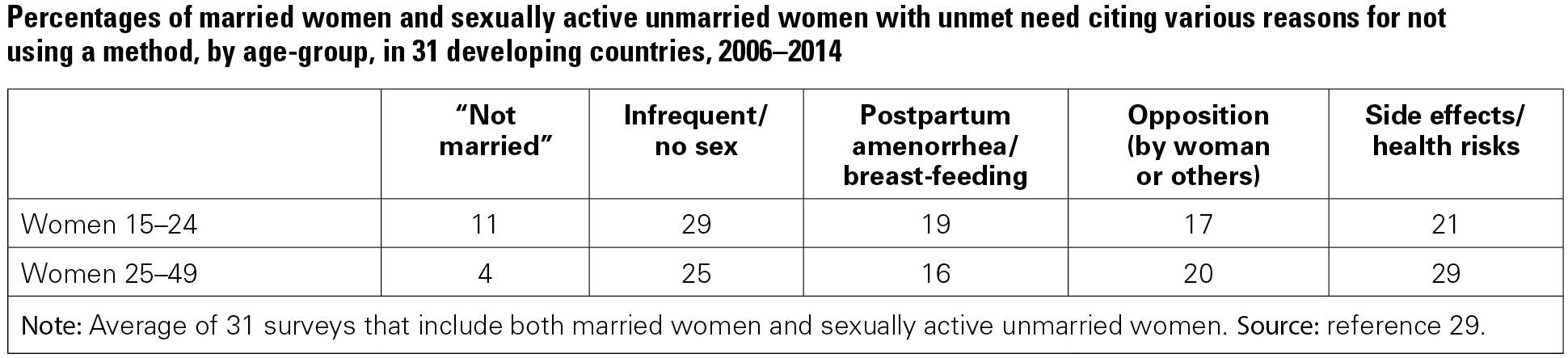

Our analysis of data from DHS in 52 countries shows that young women aged 15–24 are more likely to have an unmet need for contraception than peers aged 25–49 (see table below and Table 14). These data include all married women and sexually active unmarried women who want to avoid a pregnancy.

Some of the difference in unmet need between younger and older women is due to the fact that sexually active never-married women fall predominantly in the younger group, and they have much higher unmet need than do older, married women. Still, even married women aged 15–24 have somewhat higher unmet need for contraception than their older counterparts. In addition, women aged 15–19 years, whether they are married or not, consistently have higher unmet need than women aged 20–24.

Although women of different ages face different personal circumstances, the reasons they cite for not using contraception in spite of not wanting a pregnancy are similar. Four reasons are most common (see table below):

- infrequent or no sex (even though they are categorized as sexually active);

- postpartum amenorrhea (not having resumed menstruation after a birth), breast-feeding or both;

- opposition to contraception (by the woman or someone close to her); and

- concern about the methods themselves—their side effects, health risks or inconvenience.

Among young women who want to avoid a pregnancy, 11% say they are not using a method because they are "not married," and smaller proportions report being unaware of contraception, lacking access to a source, or being subfecund or infecund (not shown).

Younger women cite "not married" as a reason for nonuse more often than older counterparts, possibly reflecting that younger women have more sporadic sexual relationships (especially those who are unmarried). Alternately, they may believe it would be inappropriate to seek contraceptive services, or they may not want to expose their illicit activity.

Women aged 15–24 cite "infrequent or no sex" as a reason for nonuse slightly more often than do older women (29% compared with 25%, respectively—Appendix Table 8), most likely reflecting the fact that some of the young women with unmet need are unmarried and have more sporadic sexual relationships than married women. An exception to this pattern can be seen in the Philippines, where older women are much more likely to cite infrequent sex as a reason than are younger women (40% vs. 28%, respectively).

On average, younger women are slightly more likely than older peers to report postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both as a reason for nonuse—probably reflecting that births occur more often among the former, especially in Africa. The differences are small, however.

On the other hand, older women are generally slightly more likely than younger women to cite opposition to contraceptive use, although it is still a major reason for nonuse for both groups.

Fewer younger women with unmet need cite concerns about side effects and health risks compared with older women—21% versus 29%, respectively. The gap between age-groups is more than 10 percentage points in Bolivia, Guyana, Haiti, Congo, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zambia. Given that contraceptive prevalence is low in these countries, the results could indicate that fewer younger women have tried a method and experienced side effects themselves. Nevertheless, these concerns remain common among women of all ages and merit greater attention.

All young women need correct information about their risk of becoming pregnant and about the choices of contraceptive methods that are most suited to their circumstances. An obvious area for improvement is in the counseling provided in family planning and other health services that serve young women. But because young women tend to be healthy and may see no reason to visit health clinics—or may feel they don’t belong there—they need to receive information elsewhere about the risks of pregnancy and the need for contraception.

Trends in the Major Reasons for Not Using Contraception

In this section, we explore trends in reasons for unmet need among married women in 39 countries having more than one DHS during 2000–2014. (Trends are not shown for sexually active never-married women because the sample sizes of those citing specific reasons for nonuse are very small.) Six of these countries are in Latin America and the Caribbean, eight are in Asia and 25 are in Africa. Appendix Figures 1–3 show trends by region for selected reasons: infrequent or no sex; side effects, health risks or inconvenience; postpartum amenorrhea or breast-feeding; opposition; and lack of a source for or access to contraception.

In countries where the proportion of married women with unmet need has declined, the proportions citing specific reasons for nonuse are based on a smaller pool of women, relatively speaking. However, two factors determine the absolute number of women experiencing the barriers cited: the proportion with unmet need and the total population of women, which has increased over time because of population growth.

General Trends in Married Women’s Reasons for Nonuse

In most of the 39 countries with data allowing assessment of trends, growing proportions of married women with unmet need cite infrequent or no sex as a reason for not using contraception. As noted earlier, some of these women are abstinent and not currently at risk for unintended pregnancy; others may perceive their risk to be lower than it actually is; and still others may know that they face some risk but believe that it does not warrant seeking a contraceptive method.

Given the large number and diversity of countries in which infrequent or no sex has grown in importance as a reason for nonuse, these perceptions and experiences merit greater attention in research and program planning. The growing frequency of this response could reflect increases in migration in some countries: For example, in Nepal, 32% of all married women reported that their husbands were away in 2011, compared with 17% in 1996.37 In India, nearly 10% of married women lived without their husbands in 2006, compared with only 5% in 1999. Also, the higher proportion of women citing infrequent or no sex could indicate that programs and services have addressed other reasons for nonuse of contraception; the women who remain with an unmet need are those who are less sexually active and do not believe they need contraception.

The cost of methods and access to a source have remained uncommon reasons for nonuse. Their levels fluctuate, however, and may merit further investigation in some countries. As noted earlier, the data likely underestimate the prevalence of this barrier because other reasons discourage women from even trying to obtain services. But the general trends suggest that family planning programs have had a considerable impact in raising women’s awareness about contraception and where and how to obtain it.38 Public support for family planning, whether from national governments or external donors, might have kept the cost acceptable for users in developing countries.

National family planning programs may also have had some effect on opposition to contraception, but trends in the proportions of women citing this reason are mixed. Concerns about side effects and health risks have become more prevalent reasons for nonuse in the majority of countries in this analysis, possibly because more women have been exposed to the real side effects of contraceptive methods or to misinformation about the problems associated with use.11,17,34,39 There are some exceptions in each region where the prevalence of this reason has remained the same or declined. Still, it remains one of the most important reasons for nonuse of contraception in all countries over the 14-year period.

Regional and Country Trends in Reasons for Nonuse

Some noteworthy similarities and differences in trends are evident across the three world regions and the individual countries.

Latin America and the Caribbean

Trends for the six countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are shown in Appendix Figures 1a–e. Concern about the side effects and health risks of contraceptives has been and remains the most common reason for nonuse in this region, and it is highest in Haiti, where about half of married women with unmet need cite this reason. Infrequent or no sex has also remained a common reason for nonuse. The increase in this reason is particularly pronounced in Bolivia and Peru. Access barriers were low and continued to decrease over time, except for an increase (but still at a low level) in the Dominican Republic. Postpartum amenorrhea, breast-feeding or both has not been a common reason for nonuse in this region, but it has become more so in Bolivia. Notably, opposition to contraceptive use increased as a reason for nonuse in Haiti, rising from 17% of women in 2000 to 36% in 2012.

Asia

Trends for the eight countries in Asia are shown in Appendix Figures 2a–e. Women increasingly cite infrequent or no sex as a reason for nonuse in all of the Asian countries shown. Between 2000 and 2014, the prevalence of this reason increased dramatically, from 31% to 57% of married women in Bangladesh, from 35% to 73% in Nepal, and from 17% to 37% in the Philippines. We speculate these increases were largely due to increased labor migration.40

Across this region, concern about side effects or health risks is fairly common, but trends have been mixed: its prevalence has declined in Armenia, Indonesia and Nepal, but has remained the same or increased in the other four Asian countries. It is highest in Cambodia, where about half of married women with unmet need cite this reason. Opposition to contraception is the third most common reason in Asia; it appears to have increased in recent years in Armenia, Pakistan and the Philippines. Postpartum amenorrhea or breast-feeding is comparatively less frequently cited as a reason for nonuse, and it declined in Nepal in particular, from 28% to 9% of married women with unmet need. Access barriers remain low across this region.

Africa

Trends for the 24 countries in Africa are shown in Appendix Figures 3a–e. Infrequent or no sex is increasingly cited as a reason for nonuse in some African countries, but levels have not reached those of other regions. Concern about side effects or health risks has increased by five percentage points or more in all but six African countries. Previous studies have suggested that this concern is likely to be linked to women’s growing contraceptive use and direct experiences of side effects, or the experiences of their friends.11,31,33,36

Although the prevalence of postpartum amenorrhea/breast-feeding as a reason for nonuse might be expected to decline over time with reductions in both fertility and the duration of breast-feeding, it has remained the same or increased in 20 of the 24 African countries (exceptions are Egypt, Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania).

Also, in spite of many years of family planning program efforts in Africa, opposition to family planning as a reason for nonuse increased or stayed roughly the same since 2000 in 23 of the 24 countries in this analysis. (Malawi is the exception.) The factors underlying the mixed trends are unclear, as the responses could stem from conservative social values or factors having to do with the methods themselves, such as side effects.

Offsetting these increases, lack of a source of contraception or access to one as a reason for nonuse has declined or remained at a low level in all 24 African countries. Drops of five percentage points or more can be seen in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda and Uganda.

Conclusions and Recommendations

For the past two decades, international family planning programs have focused on enabling women and couples to choose the number and timing of their children, and on protecting women’s reproductive health and rights. The concept of unmet need is central for formulating policies and planning programs to meet these objectives. It is also an essential measurement for national programs aimed at helping women and couples avoid unintended pregnancies. To design effective programs, planners and decision makers need to understand the reasons why women with unmet need are not using contraceptives.

Key Findings