Introduction

Previous Guttmacher Institute research has described sexual and reproductive health disparities between immigrant women and their US-born counterparts.1 We present new analyses, based on two nationally representative surveys, that show inequities in health insurance coverage by citizenship status and race or ethnicity, and health care service use by citizenship status. These new findings are consistent with existing evidence indicating a need for policies to eliminate sexual and reproductive health inequities that have long persisted along lines of race and ethnicity, immigration status and income in the United States.2

These analyses make it clear that policymakers need to address these inequities. Two bills, the Health Equity and Access Under the Law (HEAL) for Immigrant Families Act3 and the Lifting Immigrant Families Through Benefits Access Restoration (LIFT the BAR) Act,4 represent opportunities to do just that.

Findings

Health insurance disparities by race and citizenship status

Of the nearly 151 million people aged 15−49 in the United States, 14.6 million people—almost one in 10—are noncitizen immigrants. Noncitizens include people who hold visas or green cards (permanent residents), have temporary protected status, are "out of status" (hold expired visas or entered the country without a visa) or have been granted deferred enforcement of deportation, such as that provided by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The sources used for these analyses, the American Community Survey (ACS)5 and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS),6 do not collect data on these categories, so we analyzed all noncitizen immigrants as a single group.

Most noncitizens of reproductive age living in the United States identify as Black or African American, Asian, Hispanic or Latino,* or multirace (88.5%); 11.5% identify as White. Fewer naturalized citizens (83%) and US-born citizens (37%) identify as non-White or multirace.

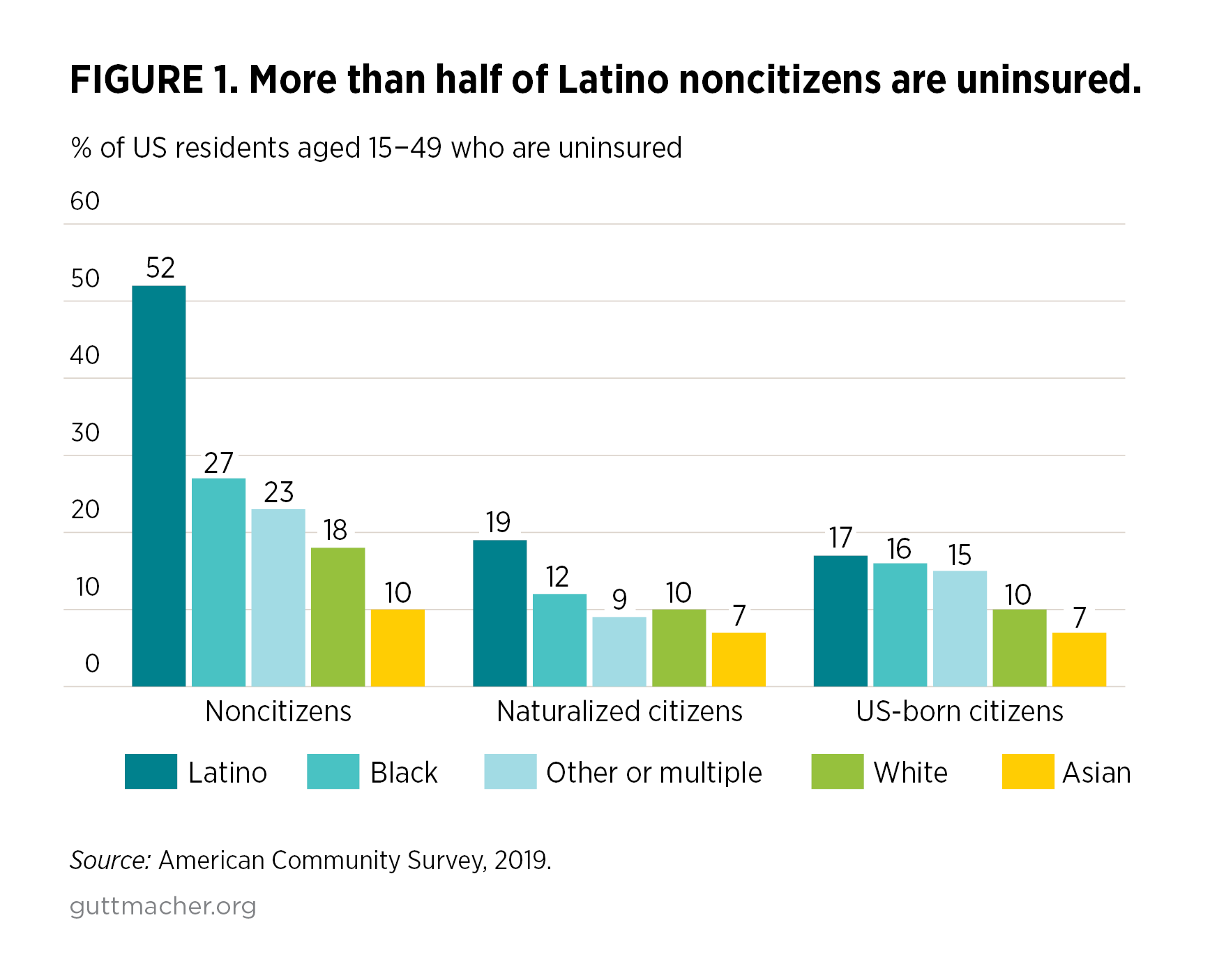

In our analysis of the 2019 ACS, we found that higher proportions of noncitizens of every race and ethnicity were uninsured compared with the proportions among their US-born and naturalized counterparts (Figure 1). While this demonstrates that barriers to obtaining health insurance coverage for noncitizens harm people of all races and ethnicities, we also found that higher proportions of Latino and Black noncitizens than of naturalized and US-born citizens of any race or ethnicity were uninsured.

We also found that:

- More than one-half of Latino noncitizens were uninsured. A higher proportion of Latino noncitizens than of Latino citizens (52% vs. 17%) and White citizens (52% vs. 10%) were uninsured.

- More than one-quarter of Black noncitizens did not have health insurance (27%), compared with White noncitizens (18%), Black US-born citizens (16%), Black naturalized citizens (12%) and White US-born citizens (10%).

- Across all citizenship categories, a higher proportion of Asians than of other racial and ethnic groups had health insurance. This does not suggest that Asian communities escape the institutional and interpersonal racism that impede health care access. "Asian" is not a monolithic category in the United States; rather, it comprises hundreds of cultures, sociopolitical histories, countries and language communities. However, detailed data that would allow us to understand this diversity more clearly are not available. Some Asian communities may in fact lack health insurance at high rates that remain hidden without sufficient data by ethnicity, country of origin or documentation status. Indeed, an estimated one in seven Asian immigrants in the United States are undocumented7 and likely do not have access to health insurance.

It is possible that the broad category of "noncitizen" masks even greater disparities in health insurance coverage because many polices excluding immigrants from health care access target particular noncitizen immigration statuses.8 For example, DACA recipients and immigrants who are "out of status" are barred from purchasing health insurance with their own money on state exchanges established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Primary care access and noncitizen immigrants

We assessed differences in receipt of health care services by citizenship status among US residents aged 18−49, using the 2017−2018 NHIS. Across several measures, noncitizen immigrants were less likely to report receiving primary health care services than US-born and naturalized citizens. The lower use of these services among noncitizens compared with the use among citizens is not surprising given the stark inequities in health insurance coverage between these groups, and the fact that paying out of pocket for care is too expensive for many people.

There were disparities between noncitizens and citizens in receiving primary care services.

- A higher proportion of noncitizens than of naturalized citizens and US-born citizens reported they had not had an in-person visit at a doctor’s office, clinic or "other place" in the past year (40% vs. 23% and 20%, respectively).

- One in five (21%) noncitizens had not seen or spoken to a health provider most likely to provide sexual and reproductive health services† in the past year, compared with 13% of naturalized citizens and 10% of US-born individuals.

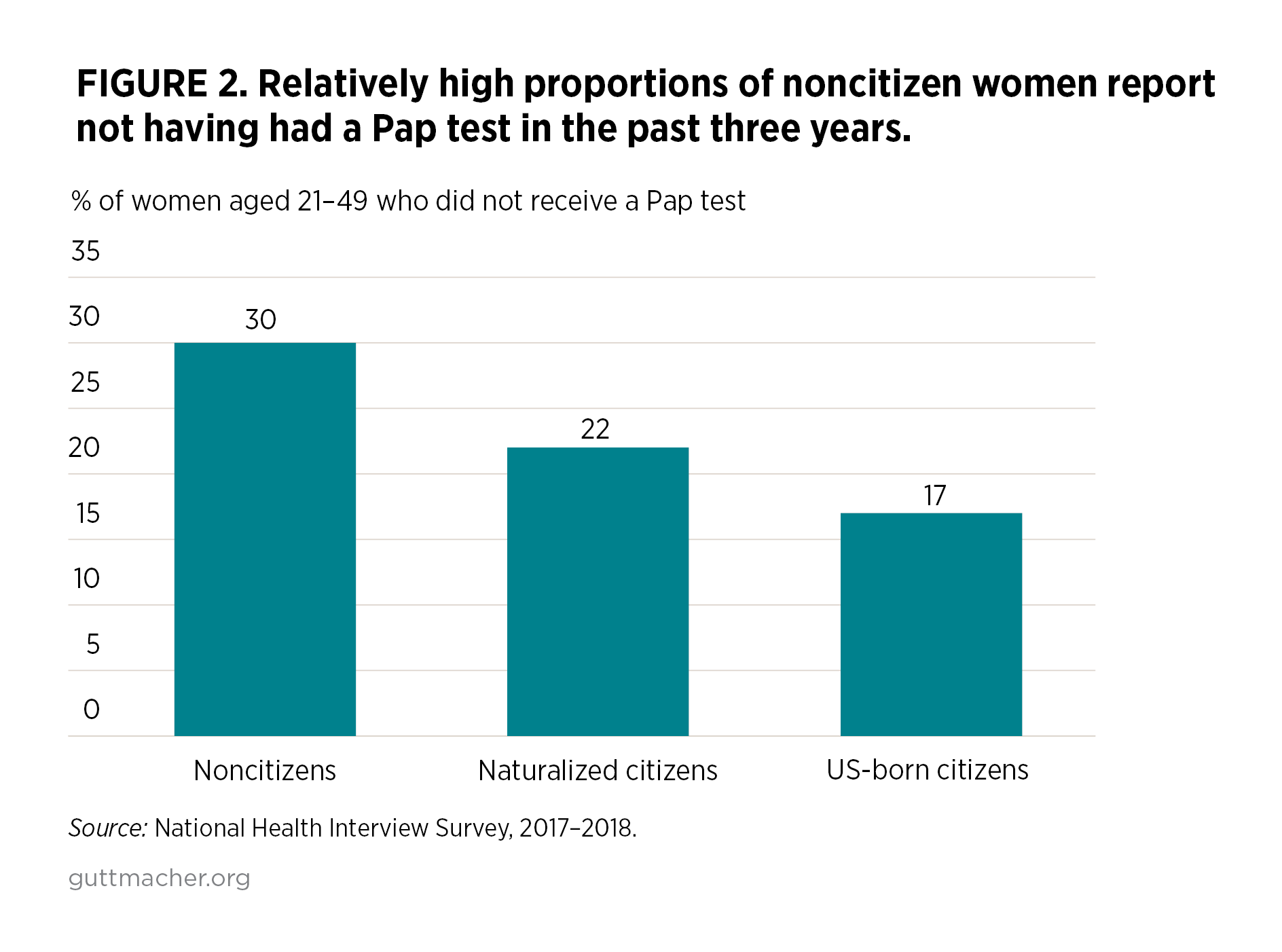

- The proportion of women aged 21−49‡ who had not had a Pap test in the past three years was nearly twice as high among noncitizens (30%) as among US-born individuals (17%) (Figure 2).

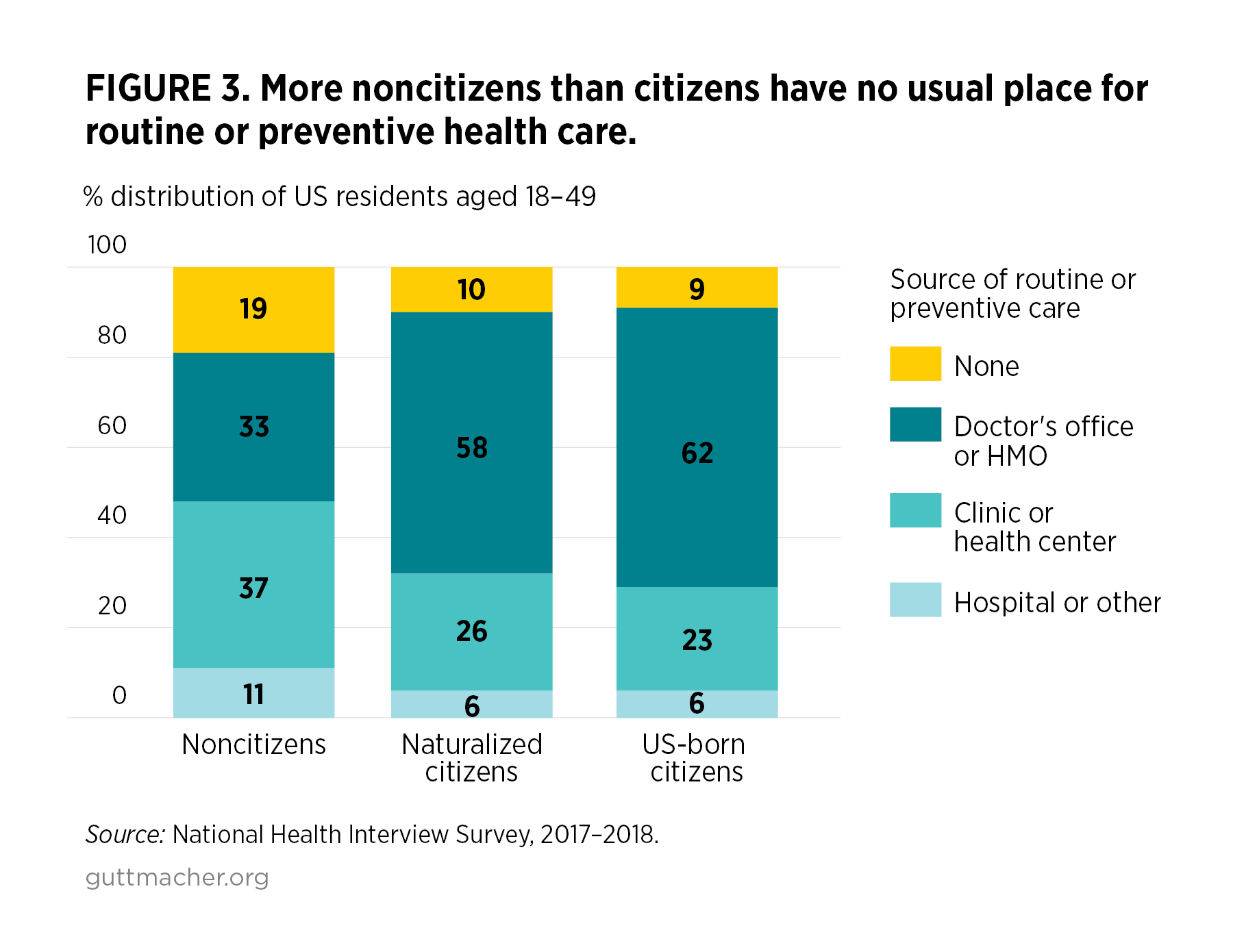

We found similar disparities when analyzing where people go for routine health care needs (Figure 3).

- One in five (19%) noncitizens reported having no usual place for routine or preventive care, compared with 10% of naturalized citizens and 9% of US-born individuals.

- A higher proportion of noncitizens (37%) than of naturalized citizens (26%) and US-born people (23%) reported that their usual place for routine care was a clinic or health center. Clinics and health centers may be more likely to have sliding-fee scales, have the Federally Qualified Health Center certification and receive public funding like Title X family planning grants, allowing them to provide care without regard to immigration or citizenship status. These results underscore that publicly funded clinics remain critical sources of high-quality health care for immigrants.9

- One-third of noncitizens (33%) reported that a doctor’s office or health maintenance organization was their usual source for routine care, compared with 62% of US-born individuals and 58% of naturalized citizens. These types of facilities may be more likely to require health insurance coverage or out-of-pocket payment. These payment options may be out of reach for those who cannot obtain health insurance because of their immigration status and who are unlikely to be able to pay the full out-of-pocket cost.

Discussion

These new analyses of ACS and NHIS data illustrate the disparities in access to health insurance, as well as routine and preventive health services, for noncitizen immigrants compared with their citizen counterparts, particularly for immigrants of color.

Federal and state policies limit access to affordable, comprehensive health insurance for people who were born outside the United States. Since 1996, federal law has deemed most legal permanent residents ineligible for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) during their first five years of residence in the United States. Similarly, certain immigrants are barred from purchasing a health insurance plan on the exchanges established under the ACA.

These policies target immigrants who are not US citizens and who currently lack a viable pathway to citizenship based on length of residency or immigration status. Policies that intentionally exclude certain immigrants from accessing government-subsidized health insurance, such as Medicaid, or from purchasing a health insurance plan with their own money on the exchanges established under the ACA violate people’s basic right to health care and undermine public health.

Policy recommendations

Our analyses add to the evidence base showing a critical need to eliminate policies that prevent health equity by denying immigrants’ access to health care. Some progress is being made on the state level. For example, Colorado has established a free reproductive health program for undocumented state residents.10 Federal policymakers have an opportunity to support two important bills that would work in concert to expand immigrants’ ability to get health insurance and access essential health services:

- The HEAL for Immigrant Families Act would remove the five-year waiting period for Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, as well as remove restrictions from the ACA that prevent undocumented immigrants from accessing marketplace health insurance plans. The bill also enables people granted deferred enforcement of deportation—most notably, those with DACA—to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP if they are eligible, buy private insurance coverage on the ACA marketplaces and obtain the ACA’s subsidies designed to make coverage affordable.3

- The LIFT the BAR Act would restore access to public programs for "lawfully present" immigrants11 by removing the five-year waiting period and other restrictions on access to essential federal public benefits that promote the health and well-being of children and families. These programs include Medicaid, CHIP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Security Income, certain housing assistance and other important services.4

Conclusion

All people living in the United States, regardless of where they are born, deserve health insurance and high-quality health services. Yet our analyses demonstrate that disparities by immigration status in access to health insurance, as well as primary and reproductive health care, persist—and that these disparities are magnified for immigrants of color. The HEAL for Immigrant Families Act and the LIFT the BAR Act are critical opportunities to address and eliminate these harmful inequities.

Methods

We analyzed data from two sources: the 2019 American Community Survey and the 2017−2018 National Health Interview Survey. We calculated weighted frequency and percentage distributions of the characteristics described. For analyses of both the ACS and NHIS data, 95% confidence intervals and chi-square tests were used to assess statistical significance; all comparisons presented were significant at p≤.05.

Footnotes

*Survey respondents can choose to identify as being of "Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin." Those who responded "yes" are described in this report as "Latino" to reflect the survey language and for brevity. We recognize that US residents of Latin American origin may prefer or identify using other terms, including Latinx, Latine and other culturally or geographically specific identities.

†This category included nurse practitioner, physician assistant, midwife, obstetrician-gynecologist and general practitioner.

‡The question about receipt of a Pap test in the past three years was restricted to female respondents who had not had a hysterectomy.

References

1. Hasstedt K, Desai S and Ansari-Thomas Z, Immigrant Women’s Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Coverage and Care in the United States, New York: Commonwealth Fund, 2018, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/Hasstedt_immigrant_women_access_coverage_ib.pdf.

2. Guttmacher Institute, Immigrants’ health insurance: Federal restrictions are harmful for sexual and reproductive health, Fact Sheet, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2021, https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/immigrants-coverage-policy.

3. National Asian Pacific American Women's Forum, HEAL for Immigrant Families Act, no date, https://www.napawf.org/heal.

4. Protecting Immigrant Families, Resources on the LIFT the BAR Act, no date, https://protectingimmigrantfamilies.org/resources-on-the-lift-the-bar-act.

5. US Census Bureau, Accessing PUMS data: 2019, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata/access.2019.html.

6. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Health Interview Study: NHIS data, questionnaires and related documentation, no date, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm.

7. Migration Policy Institute, Profile of the unauthorized population: United States, no date, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US.

8. Dawson R and Sonfield A, Conservatives are using the intersection of immigration, health care and reproductive rights policy to undermine them all, Guttmacher Policy Review, 2020, 23:19–25, https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2020/04/conservatives-are-using-intersection-immigration-health-care-and-reproductive-rights.

9. Frost JJ, Mueller J and Pleasure ZH, Trends and Differentials in Receipt of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in the United States: Services Received and Sources of Care, 2006–2019, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2021, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/sexual-reproductive-health-services-i….

10. Miller F, 2021 brought progressive immigration policies to Colorado, Colorado Newsline, Nov. 17, 2021, https://coloradonewsline.com/2021/11/17/2021-progressive-immigration-policies-colorado.

11. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, HealthCare.gov, Coverage for lawfully present immigrants, 2017, https://www.healthcare.gov/immigrants/lawfully-present-immigrants.