Sexuality is a fundamental aspect of being human, and sexual activity is a basic part of human development for young people in the United States. As they develop, adolescents and young adults need access to evidence-based, holistic and nonstigmatizing information, education and services that support their lifelong sexual and reproductive health and well-being. The findings included in this fact sheet about adolescent sexual and reproductive health in the United States are the most current available, drawn primarily from recent nationally representative surveys. Although these data have limitations (see accompanying box), they still provide important insights into young people’s experiences and needs.

Limitations

Data are a powerful tool, but available data are not without their limitations. The national survey data from which this resource draws cannot fully represent the context in which a young person’s health behavior and decision making occurs. In addition, not all populations are included or appropriately represented in the available data. This fact sheet presents the best available data on this issue.

SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

- During adolescence, many young people engage in a range of sexual behaviors and develop romantic and intimate relationships.1,2

- In 2013–2014, 20% of 13–14-year-olds and 44% of 15–17-year-olds reported that they had ever had some type of romantic relationship or dating experience.3

- In 2013–2015, 90% of adolescents aged 15–19 identified as straight or heterosexual, while 5% of males and 13% of females reported their sexual orientation as lesbian, gay, bisexual or something else.4

- Masturbation is a common behavior during adolescence; in a national sample of young people aged 14–17, reports of ever having masturbated increased with age and more males reported masturbation than females (74% vs. 48%).5

SEXUAL INTERCOURSE

- Partnered sexual activity may include a range of behaviors. In 2015–2017, 40% of adolescents aged 15–19 reported ever having had penile-vaginal intercourse (commonly referred to as "sexual intercourse"), 45% had had oral sex with a different-sex partner and 9% reported ever having had anal sex with a different-sex partner.6

- Overall, the share of 15–19-year-olds that has had sexual intercourse has remained steady in recent years.7 But among the narrower population of high school students, there was a decline in 2013–2017 in the proportion that had ever had sexual intercourse—from 47% to 40%.8

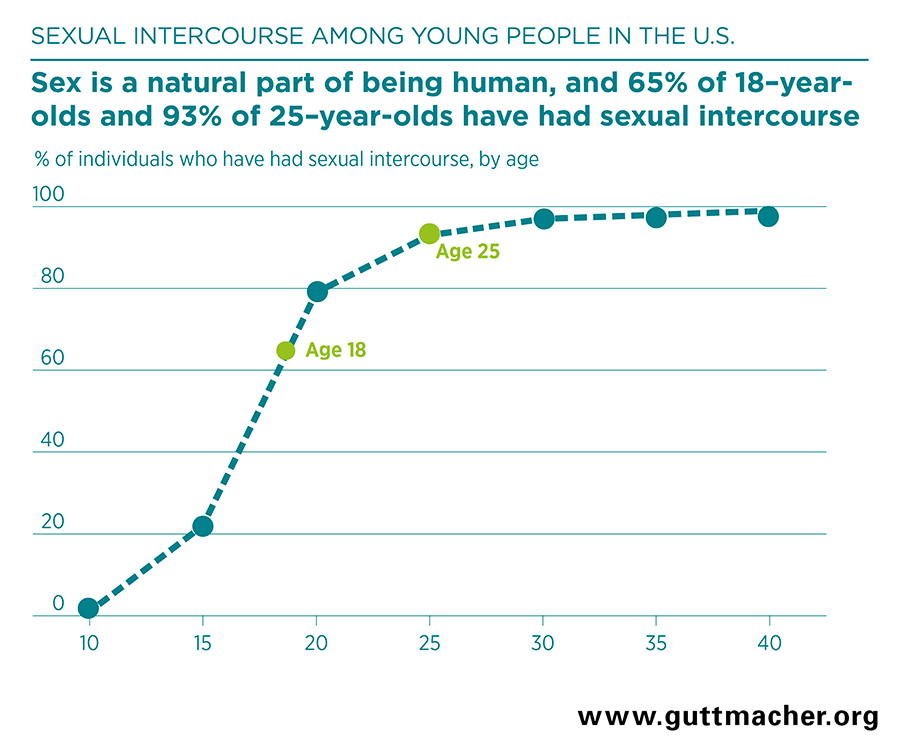

- The proportion of young people who have had sexual intercourse increases rapidly as they age through adolescence. In 2013, about one in five 15-year-olds and two-thirds of 18-year-olds reported having had sex (Figure 1).9

- Among adolescents aged 15–19 in 2015–2017 who had had penile-vaginal sex, 75% of females and 48% of males reported that their first intercourse was with a steady partner.6

- As of 2015–2017, among young people aged 18–24 who have had penile-vaginal sex, 71% of men described their first sexual experience as wanted, as opposed to unwanted (4%) or that they had mixed feelings (25%). One-half of young women said they had mixed feelings (51%), while 45% said first sex was wanted and 4% said it was unwanted.6

- Among young people aged 18–24 in 2015–2017, 13% of females and 5% of males reported that they had ever been forced to have vaginal sex.6

CONDOM AND OTHER CONTRACEPTIVE USE

- Use of condoms and other contraceptives reduce adolescents’ risk of pregnancy and HIV and STI transmission.10,11 There is no one best contraceptive method for every adolescent. Decision making about method choice should reflect individuals’ needs and priorities.

- Most adolescents use contraceptives at both first sex and most recent penile-vaginal sex. In 2015–2017, 89% of females and 94% of males aged 15–19 reported that they or their partner had used contraceptives the last time they had sexual intercourse, and 77% of females and 91% of males reported contraceptive use the first time they had sexual intercourse.6

- The condom is the contraceptive method most commonly used among adolescents. In 2015–2017, 63% of females and 82% of males aged 15–19 reported having used a condom the first time they had sexual intercourse.6

- Older adolescents are more likely to use prescription methods of contraception, and condom use becomes less common with age.8

- Adolescents aged 14 or younger at first sex are less likely than older adolescents to use contraceptives at first sex.12

- Adolescents’ nonuse of contraceptives may be driven by many factors, including lack of access, the need for confidential care and low-cost services, a belief that they are unlikely to get pregnant and poor partner negotiation skills.13,14 In addition, some adolescents may not be using contraceptives because they want to become pregnant.15

ACCESS TO SERVICES

- Adolescents and young adults need access to confidential sexual and reproductive health care services.

- Many health care providers do not talk with their adolescent patients about sexual health issues during primary care visits. When these conversations do occur, they are usually brief; in one study of visits in 2009–2012, sexual health conversations with patients aged 12–17 lasted an average of 36 seconds.16

- Despite guidance recognizing young men’s needs for sexual and reproductive health services in recent years, many gaps remain.17-19 In a 2018 study of male patients aged 15–24, only one in 10 received all of the recommended sexual and reproductive health services.20

- Queer young people need access to health care services that are inclusive of their identities and experiences, including clinicians who are well trained in discussing and addressing the particular health concerns of members of these groups.21

Contraceptive services

- In 2019, federal law requires health insurance plans to cover the full range of female contraceptive methods, including counseling and related services, without out-of-pocket costs.22 However, some young people may not use insurance to access reproductive health services because they are not aware that these services are covered or because of confidentiality concerns.23,24 The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that minors’ privacy rights include the right to obtain contraceptive services.25

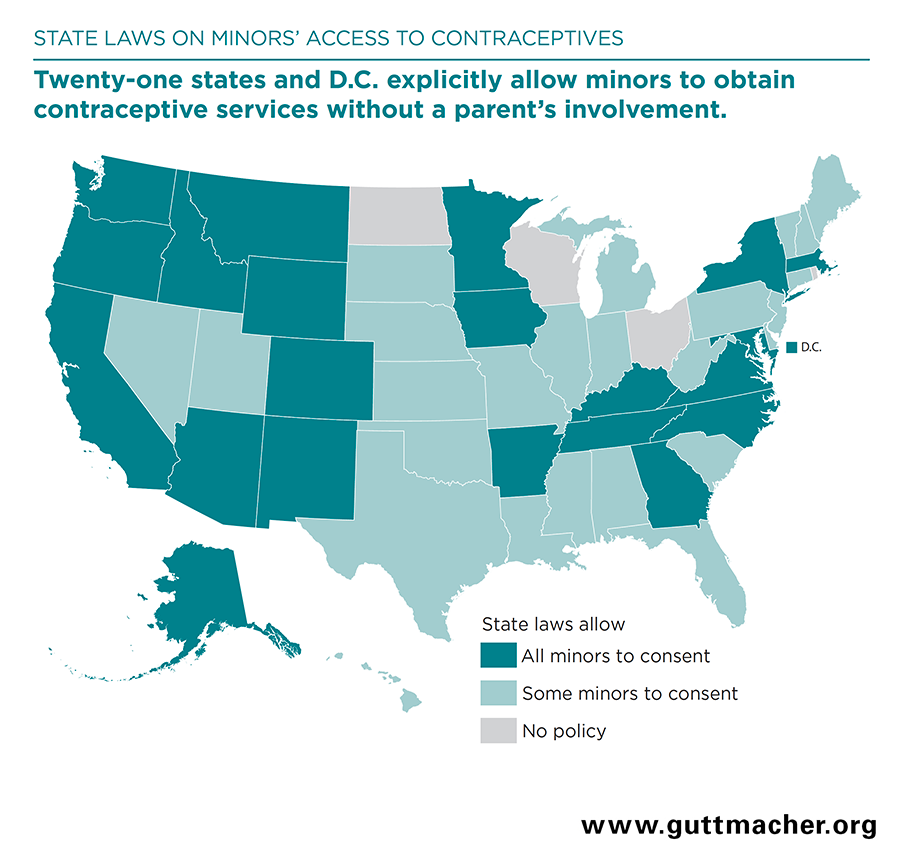

- No state explicitly requires parental consent or notification for minors to obtain contraceptive services. However, two states (Texas and Utah) require parental consent for contraceptive services paid for with state funds.25

- Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia (DC) explicitly allow minors to obtain contraceptive services without a parent’s involvement. Another 25 states have affirmed that right for certain classes of minors (e.g., a married or parenting minor), while four states do not have a statute or policy on the subject (Figure 2).25

- Even when parental consent is not required for contraceptive services, concerns about confidentiality may limit adolescents’ access to or use of contraceptive or other reproductive health services. Among females aged 15–17 who had ever had sex in 2013–2015, those who reported concerns about confidentiality were significantly less likely to have received a contraceptive service in the previous year than those who did not have these concerns.26

- In 2011–2015, 31% of females aged 15–17 and 56% of those aged 18–25 reported having received contraceptive services in the last year; about one-quarter of both age-groups had received this care from publicly funded clinics and the rest from private health care providers.27

- Nearly one million women younger than age 20 received contraceptive services from publicly supported family planning centers in 2014. These services helped adolescents to prevent 232,000 pregnancies that they wanted to postpone or avoid.28

Prevention and treatment of HIV and other STIs and related services

- All 50 states and DC explicitly allow minors to consent to STI services without parental involvement. Thirty-two states explicitly allow minors to consent to HIV testing and treatment.29

- Young people aged 13–24 accounted for about 21% of all new HIV diagnoses in the United States in 2016. Young black and Hispanic gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men are disproportionately affected.30

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a daily pill that protects against HIV, gained FDA approval for use among adolescents in May 2018.31

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that young people aged 15–24 account for half of the 20 million new cases of STIs in the United States annually, which reflects biological differences as well as likely age-based disparities in accessing preventive information and services.32

- Chlamydia accounts for nearly 20% of all STI diagnoses each year among 15–24-year-olds. Genital herpes, gonorrhea and trichomoniasis together account for about 11% of diagnoses. HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B are estimated to account for fewer than 1% of diagnoses.33

- Two-thirds of STIs diagnosed among 15–24-year-olds each year are human papillomavirus (HPV) infections.33 These infections are often asymptomatic and generally harmless but, if left undetected and untreated, can lead to cervical and other cancers.34

- HPV vaccinations are currently available to prevent the types of infections most likely to lead to cervical cancer and are recommended by the CDC for all adolescents starting at age 11.35

- HPV vaccination coverage has been improving and as of 2017, 69% of females and 63% of males aged 13–17 had received one or more doses of the vaccine.36

- Numerous studies have confirmed that increases in HPV vaccinations result in significant declines in HPV infections and related negative health outcomes.37

SEXUAL HEALTH INFORMATION AND EDUCATION

Young people need and have the right to accurate, comprehensive, inclusive information and education to support their healthy sexual development and lifelong sexual health and well-being (see box).

- States and local school districts play a large part in determining what is taught at their schools.

- Twenty-two states and DC mandate both sex education and HIV education. Two states mandate sex education only, and 12 mandate HIV education only.38

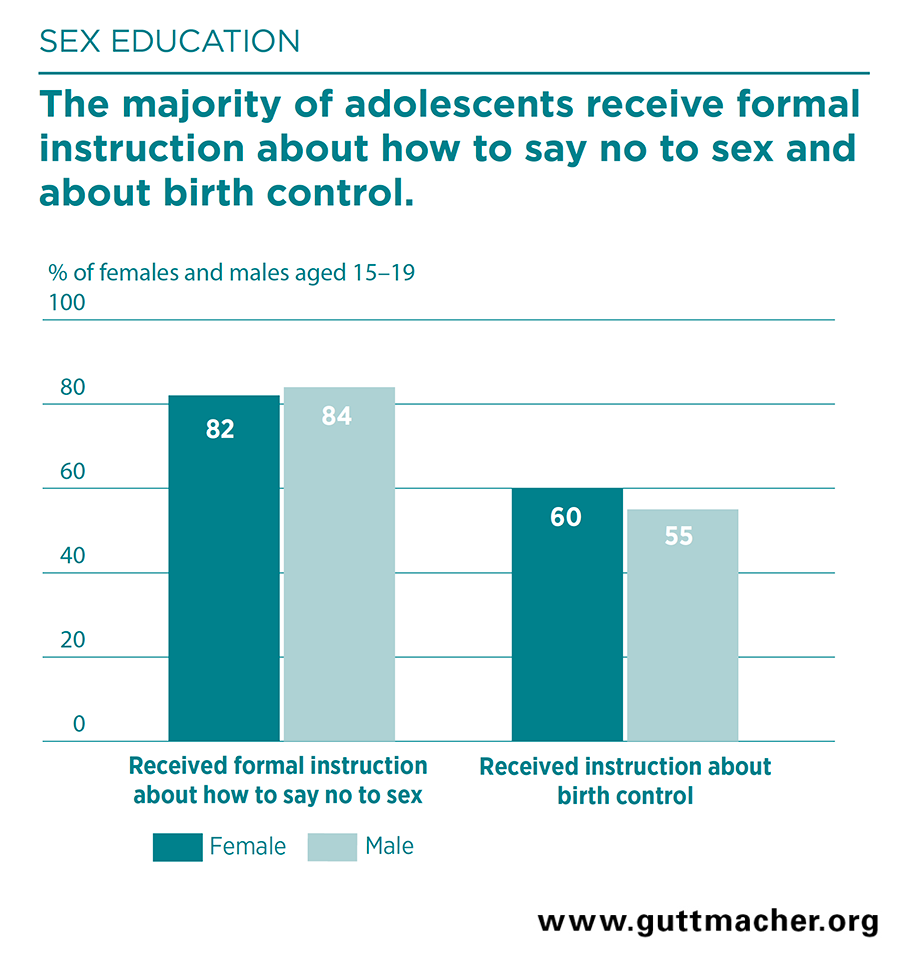

- In 2011–2013, 82% of females and 84% of males aged 15–19 received formal instruction about how to say no to sex, and 60% of females and 55% of males received instruction about birth control methods (Figure 3).39

- In 2016, the median share of schools in each state that provided instruction on all 19 topics that the CDC considers essential to sexual health education was 38% of high schools and only 14% of middle schools.40

- The share of schools providing sexual health education declined between 2000 and 2014, across many topics.41,42

- As of 2017, fewer than 7% of queer students aged 13–21 reported that their school health classes had included positive representations of LGBT-related topics.43

- Parents are another possible source of sexual health information for young people. In 2011–2013, 70% of males and 78% of females aged 15–19 reported having talked with a parent about at least one of six sex education topics: how to say no to sex, methods of birth control, STIs, where to get birth control, how to prevent HIV infection and how to use a condom.39

- Digital media offer opportunities for youth to confidentially search for information on sensitive topics44 and increasingly are being used to provide sexual health interventions for young people.

Support for Comprehensive Sex Education

Leading public health and medical professional organizations—including the American Medical Association; the American Academy of Pediatrics; the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the American Public Health Association; the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine); and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine—support comprehensive sex education.45–49