- Many of the publicly funded clinics in the four states studied in our sample left the Title X family planning program in 2018 because of a Trump-Pence administration rule that prohibited clinics from providing referrals for abortion care.

- The number of contraceptive patients served in publicly funded clinics in these four states declined between 2018 and 2021, most notably among sites that left the Title X program.

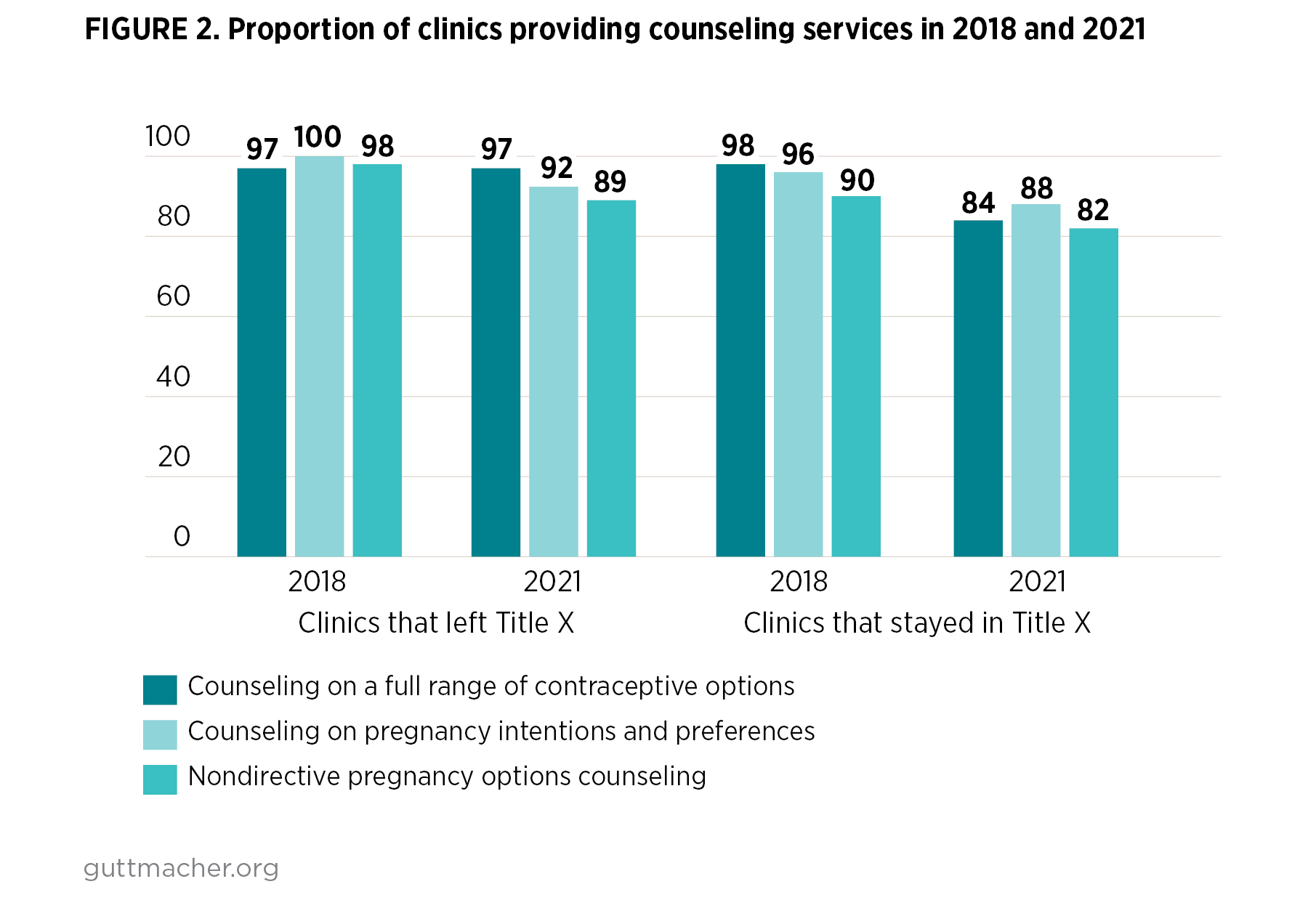

- Declines in the proportion of clinics that provided comprehensive contraceptive and pregnancy counseling were likely a result of the Trump administration’s Title X policies. For example, the proportion of clinics offering counseling on a full range of contraceptive methods fell between 2018 and 2021 among clinics that continued to receive Title X funding, while remaining high among sites that left the program.

- More clinics reported staff shortages and morale issues in 2021, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, than in 2018.

Publicly Funded Clinics Providing Contraceptive Services in Four US States: The Disruptions of the “Domestic Gag Rule” and COVID-19

Author(s)

Alicia VandeVusse, Jennifer Mueller, Ava Braccia, Samira M. Sackietey and Jennifer J. FrostReproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

Key Points

Background

The federal Title X program has been the cornerstone of publicly funded family planning care in the United States since its establishment in 1970. Title X primarily serves patients who have few financial resources, are uninsured or are young, and it does so by providing federal funding to safety-net health centers offering high-quality family planning information and care. Over the years, the Title X program has established standards that support patients in choosing contraceptive methods that align with their individual needs and preferences, through a requirement that providers offer a “broad range” of “medically approved” methods while following evidence-based standards of care.1 Furthermore, Title X follows principles of informed consent for patients and requires that care be provided confidentially.1 Title X also requires that participating sites use a sliding-fee scale that is based on certain guidelines to ensure that care is affordable.

In 2019, the Trump-Pence administration implemented changes to the regulations governing Title X. 2 Some referred to these changes as the “domestic gag rule” because Title X sites were prohibited from providing referrals for abortion care, removing a requirement to offer pregnant patients information and nondirective counseling on all options (prenatal care and delivery, adoption and abortion). In addition, the rule required separation of finances and physical space for any abortion-related services from Title X–funded services3 and mandated that all pregnant patients receive referrals to prenatal care. The rule also eliminated the requirement that family planning methods be medically approved and required that fertility awareness–based methods (FABMs) of contraception be included in the definition of family planning and that sites providing care to minors provide additional documentation of their efforts to encourage patients younger than 18 to inform a parent or guardian about their care.

During the period 2015–2018, prior to the domestic gag rule, Title X provided funds to almost 4,000 sites that collectively served about four million patients annually.4 In 2020, these numbers fell dramatically; some 3,000 sites received Title X funding and served only 1.5 million patients.5 While this decrease was due in part to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was largely a consequence of changes in the Title X network of clinics; many sites chose to leave the network rather than abide by the Trump-Pence administration restrictions. In a recent analysis, the decrease in Title X–funded sites and patients served between 2018 and 2020 was attributed, in large part (63%), to the domestic gag rule; a lower proportion (37%) was attributed to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Title X network and on the users it serves.5 While the changes to the Title X program occurred at the federal level, individual states have also implemented various policies and programs that affect how and to whom family planning services are provided.6

The Reproductive Health Impact Study is a research and policy initiative designed to document and examine the impacts of changes to federal and state policies on the family planning system in four states (Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin).6 In this report, we present longitudinal data from two waves of surveys of Title X providers operating within these states. By exploring changes between 2018 and 2021 in the number of contraceptive patients served, the on-site availability of contraceptive methods and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services, patient insurance coverage and clinic funding sources, this report sheds light on how the gag rule and the COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted clinics in these specific states during this time period. Although we are unable to fully disentangle the impacts of these pivotal events, we examine variation and change over time according to whether the clinic left the Title X program in 2019 because of the gag rule or stayed in the program throughout the study period.

Methodology

This report is based on longitudinal survey data collected from family planning clinics at two points in time. The first survey (referred to as Wave 1 or 2018) was conducted in late 2019 through early 2020 and collected data about 2018. The second survey (referred to as Wave 2 or 2021) was conducted in early 2022, collecting data about the period from mid-2020 to late 2021. Most survey questions focused on clinic-level data regarding on-site services provided, funding sources, and clinics’ reactions to policy changes and the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were also asked an open-ended question about challenges facing their clinic, and their answers were categorized by theme. Respondents were staff members, such as clinic directors and family planning administrators, from 96 sites across the four states—Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin—that provided contraceptive services during both time periods; all were at sites that received Title X funding in 2018, prior to the gag rule. Data were weighted to reflect the sample selection and response rates. We compared results across the two time periods, as well as between sites that left Title X after the implementation of the gag rule and sites that remained in the Title X program. All differences mentioned in the report are significant at least at the p<.10 level unless otherwise noted. The appendix tables, which provide data underlying the figures, indicate significance at p<.10 and p<.05. Additional information about the methods can be found in the Methodology Appendix.

Findings

Clinic characteristics

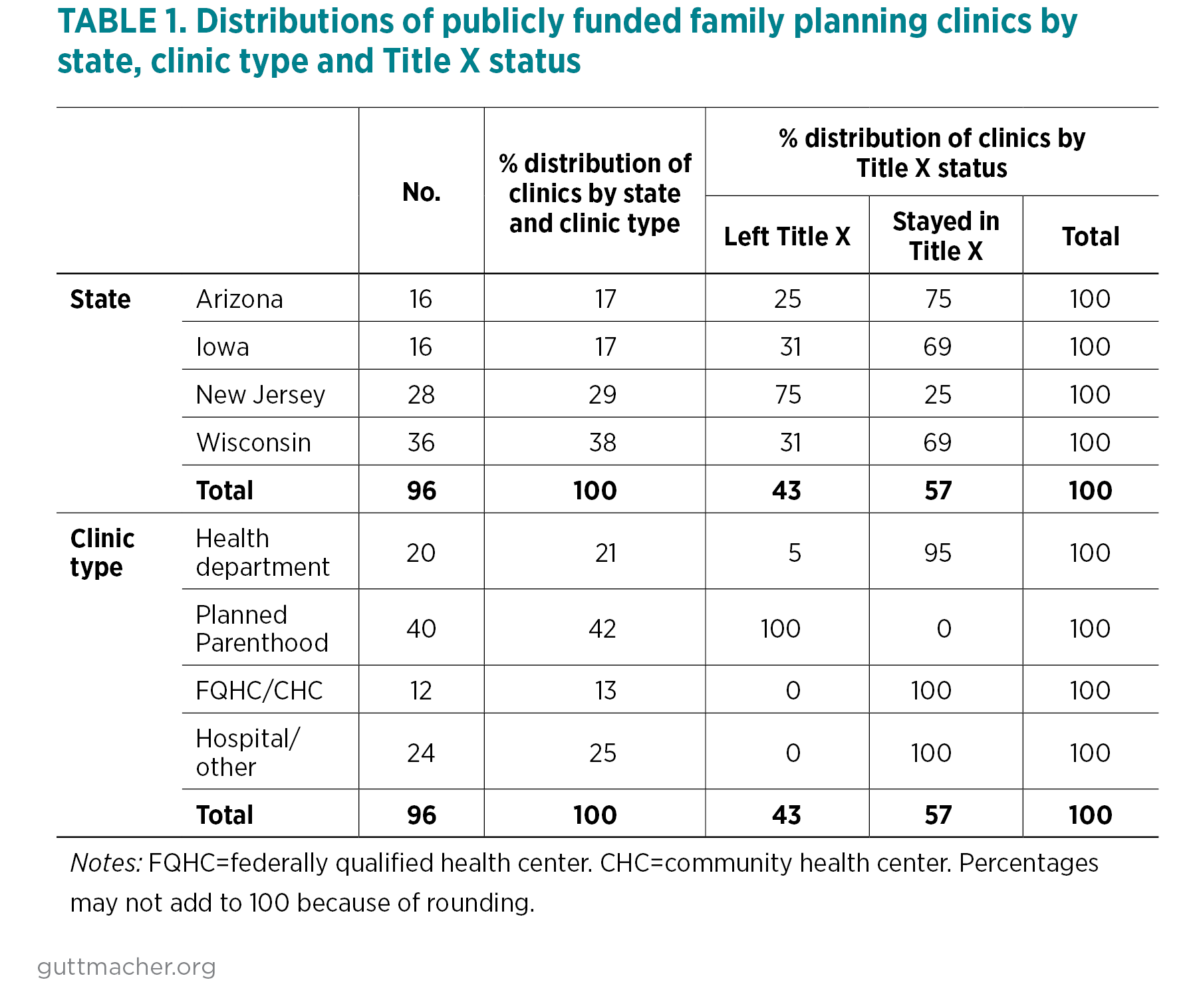

The clinics that responded to the survey were distributed across the four study states: 36 sites in Wisconsin, 28 in New Jersey, 16 in Arizona and 16 in Iowa (Table 1). Planned Parenthood sites accounted for the largest proportion of the sample (42%), followed by hospitals or other organization types (25%), health departments (21%), and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) or community health centers (13%). While almost all health departments, FQHCs and hospitals that responded continued to receive Title X funding in 2020, all Planned Parenthood facilities in the sample left the program in the wake of the gag rule. More than two-thirds of clinics in Arizona, Iowa and Wisconsin remained in the Title X program, whereas only one-quarter of clinics in New Jersey did so. This is in large part because many of the New Jersey sites were Planned Parenthood facilities. Overall, 55 (57%) of respondent clinics in all four states remained in the Title X program at both time periods while 41 (43%) left the program.

Contraceptive patients served

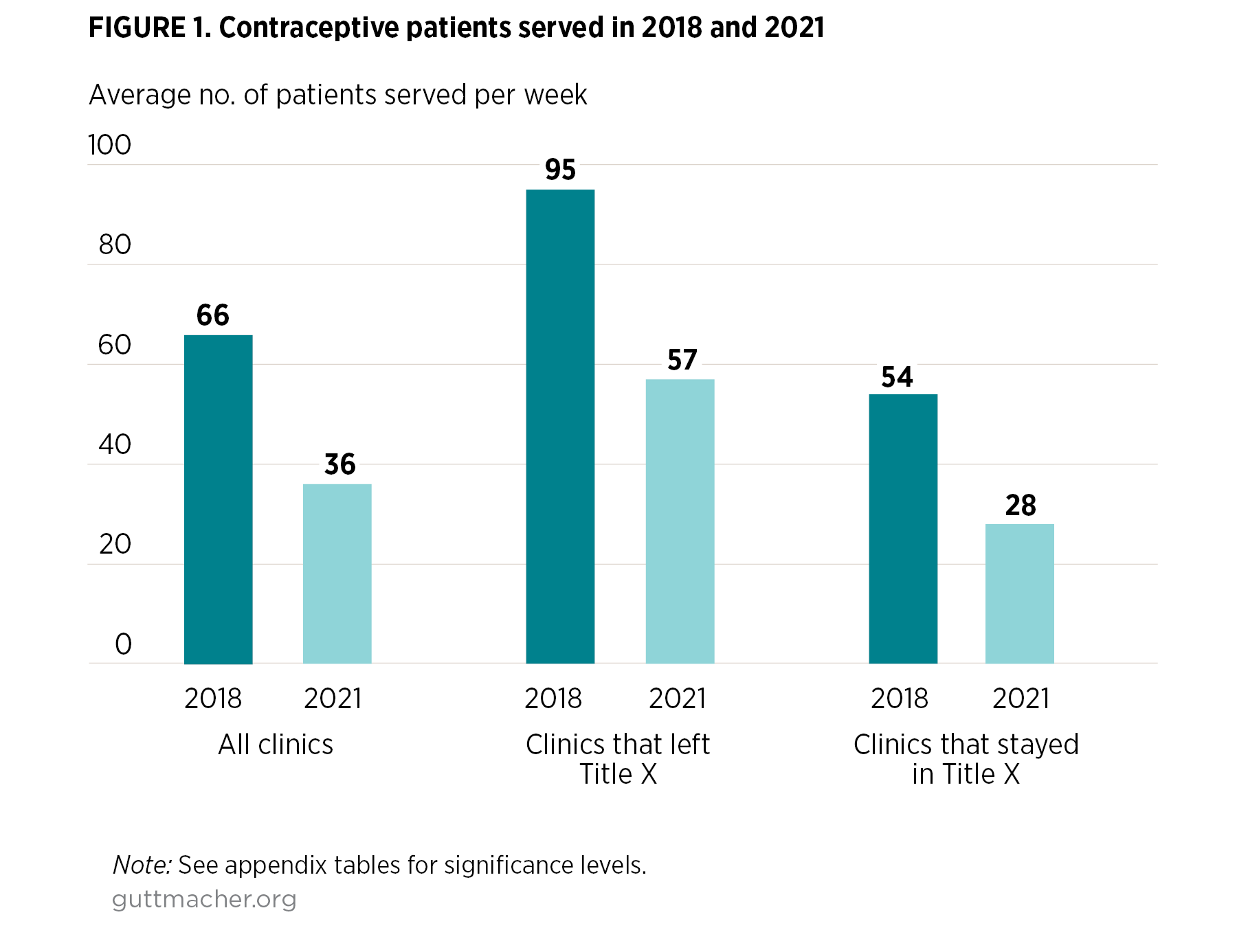

The average number of contraceptive patients served per week decreased for all clinics between data collection waves, from 66 contraceptive patients per week in 2018 to 36 contraceptive patients per week in 2021 (Figure 1). Contraceptive patient volume fell for sites that left the Title X program (95 to 57 patients per week); clinics that stayed in Title X experienced a large, though not statistically significant, drop in patient caseload (from 54 to 28 patients per week). In each time period, clinics that stopped participating in the program (primarily Planned Parenthood clinics) served a higher number of contraceptive patients on average, compared with those clinics that continued to receive funding, although these differences were statistically significant only in 2021 (57 vs. 28 contraceptive patients per week).

Availability of contraceptive methods and sexual and reproductive health services

Across the two time periods, there was little variation in weekly open hours or in the scope of contraceptive methods and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services provided. On average, clinics were open to provide contraceptive services for 33 hours per week in both time periods. Of the 12 contraceptive methods and 26 SRH services respondents were asked about, clinics provided an average of 8–10 contraceptive methods and 17–19 other SRH services on-site. Change between 2018 and 2021 in open hours and number of services provided were also similar for sites that stayed in and those that left the Title X program. However, clinics that left Title X offered a higher number of contraceptive methods than clinics that stayed in the program (9.4 vs. 8.7 in 2018 and 9.6 vs. 8.2 in 2021). This pattern was similar to the variation seen in contraceptive patient caseloads.

Trends for specific methods and services

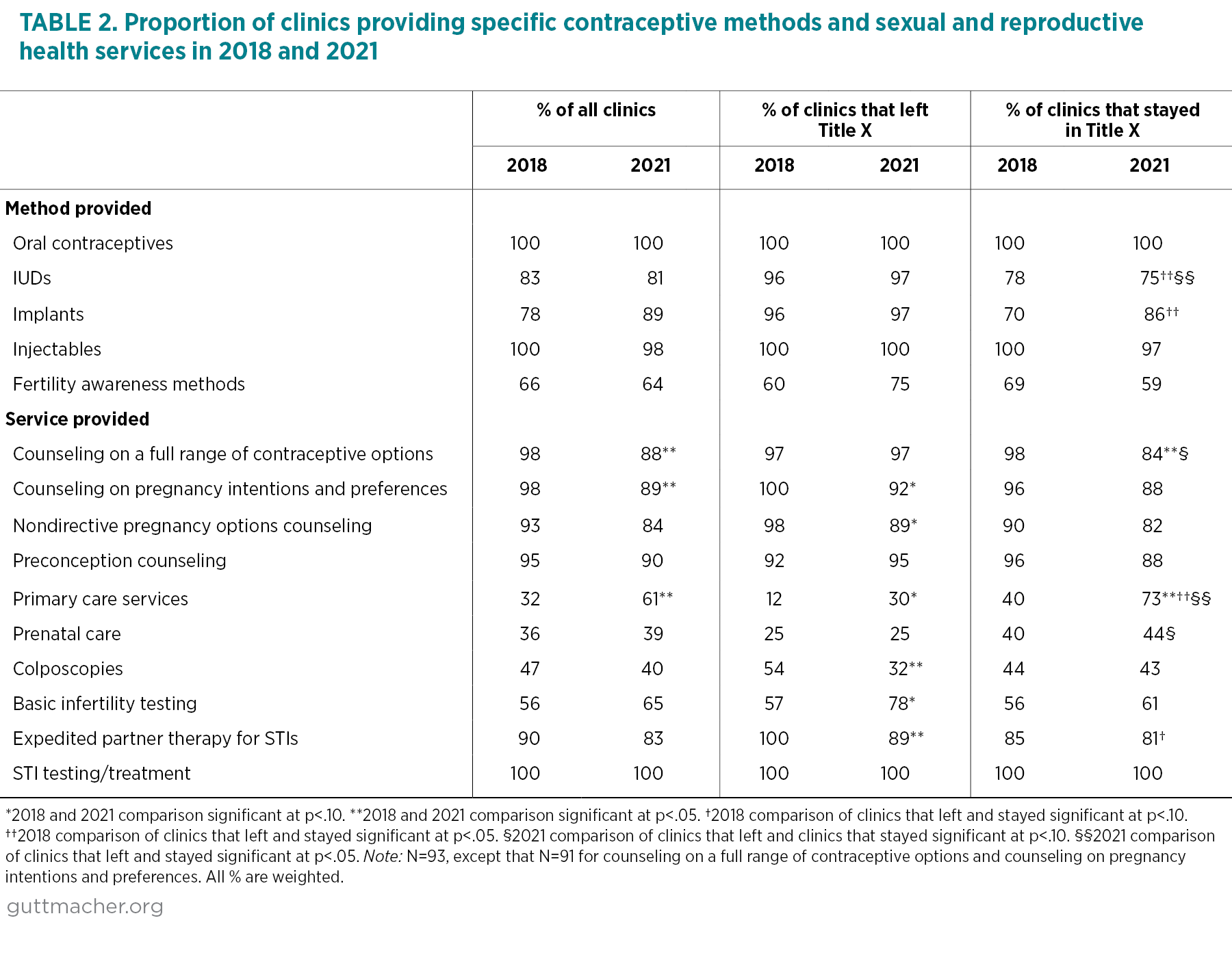

We examined trends between 2018 and 2021 in the provision of SRH and related services (Table 2). Overall, provision of oral contraceptives, IUDs and the injectable was virtually unchanged (and often universal) across time periods, as was STI treatment and testing. A higher proportion of clinics (61% vs. 32%) reported provision of primary care services in 2021, compared with the proportion in 2018.

We looked at specific contraceptive methods, SRH services, and pregnancy and contraceptive counseling practices that the gag rule may have impacted. Among all sites, the proportion of clinics reporting provision of fertility awareness–based methods (FABMs) was virtually unchanged between the two time periods. However, the share of clinics reporting that they regularly counseled patients on a full range of contraceptive options fell, from 98% in 2018 to 88% in 2021. Similarly, the share of clinics reporting that they regularly counsel patients to assess pregnancy intentions and preferences also declined during that time period (98% to 89%). Provision of nondirective pregnancy options counseling also fell during that period, but not significantly (93% to 84%).

Trends in availability by Title X status

We compared the availability of contraceptive counseling, methods and services at clinics that left the Title X program and those that stayed in the program.

- Somewhat surprisingly, between 2018 and 2021, clinics that left the Title X program reported an increase in FABM provision (from 60% to 75%), whereas clinics that remained in the program reported a decrease in provision of FABMs (from 69% to 59%). However, while these shifts were large, neither was statistically significant.

- In 2018, the share of sites that offered counseling on a full range of contraceptive options was similar and high among both groups of clinics (97–98%; Figure 2). In 2021, the same share of clinics that left the Title X program continued to offer such counseling (97%); however, the proportion of sites offering counseling on a full range of methods fell to 84% among clinics that continued to receive Title X funding.

- Although slightly higher proportions of clinics that left the Title X program reported offering nondirective pregnancy options counseling in both time periods, compared with the proportion of clinics that stayed in Title X (98% vs. 90% in 2018 and 89% vs. 82% in 2021), the differences were not significant.

- In both 2018 and 2021, nearly all (96–97%) sites that left the Title X program between data collection waves reported that they offered long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods such as IUDs and implants. In contrast, IUD provision among clinics that stayed in the program was lower in both time periods (75–78%). Implant provision among clinics that stayed in the program was lower in 2018 (70%) than in 2021 (86%), but this difference was not significant.

Trends in provision of other services

Changes over time or according to Title X status in the provision of related services may reflect decisions clinics made when faced with resource constraints or other external factors.

- Availability of primary care services varied widely, both among groups according to Title X funding status and over time. In 2018, 40% of sites that remained in the Title X program throughout the study period offered primary care services, compared with only 12% of clinics that later left Title X. By 2021, nearly three in four (73%) clinics in the former group offered primary care services, compared with 30% of the clinics that left Title X.

- Availability of prenatal care services varied among groups according to Title X funding status, but not over time. Four in ten (40–44%) clinics that stayed in Title X offered prenatal care services in both time periods, compared with one in four (25%) clinics that left the program. The difference in availability of prenatal care services between the two types of clinics was significant in 2021, but not in 2018.

- Provision of colposcopies among clinics that left the Title X program fell dramatically between 2018 and 2021 (from 54% to 32% of sites), while it remained similar (43–44%) for sites that stayed in the program.

- In contrast, among clinics that left the Title X program, the share that offered basic infertility testing rose between 2018 and 2021 (57% to 78%) and did not change significantly for clinics that stayed in Title X (56% to 61%).

- In 2018, all sites that would later leave Title X reported offering expedited partner therapy for STIs, compared with 85% of sites that would remain in the Title X program. However, by 2021, the former group experienced a decrease in the proportion offering this service (89%), while there was little change in the proportion of sites that stayed in Title X offering this service (81%).

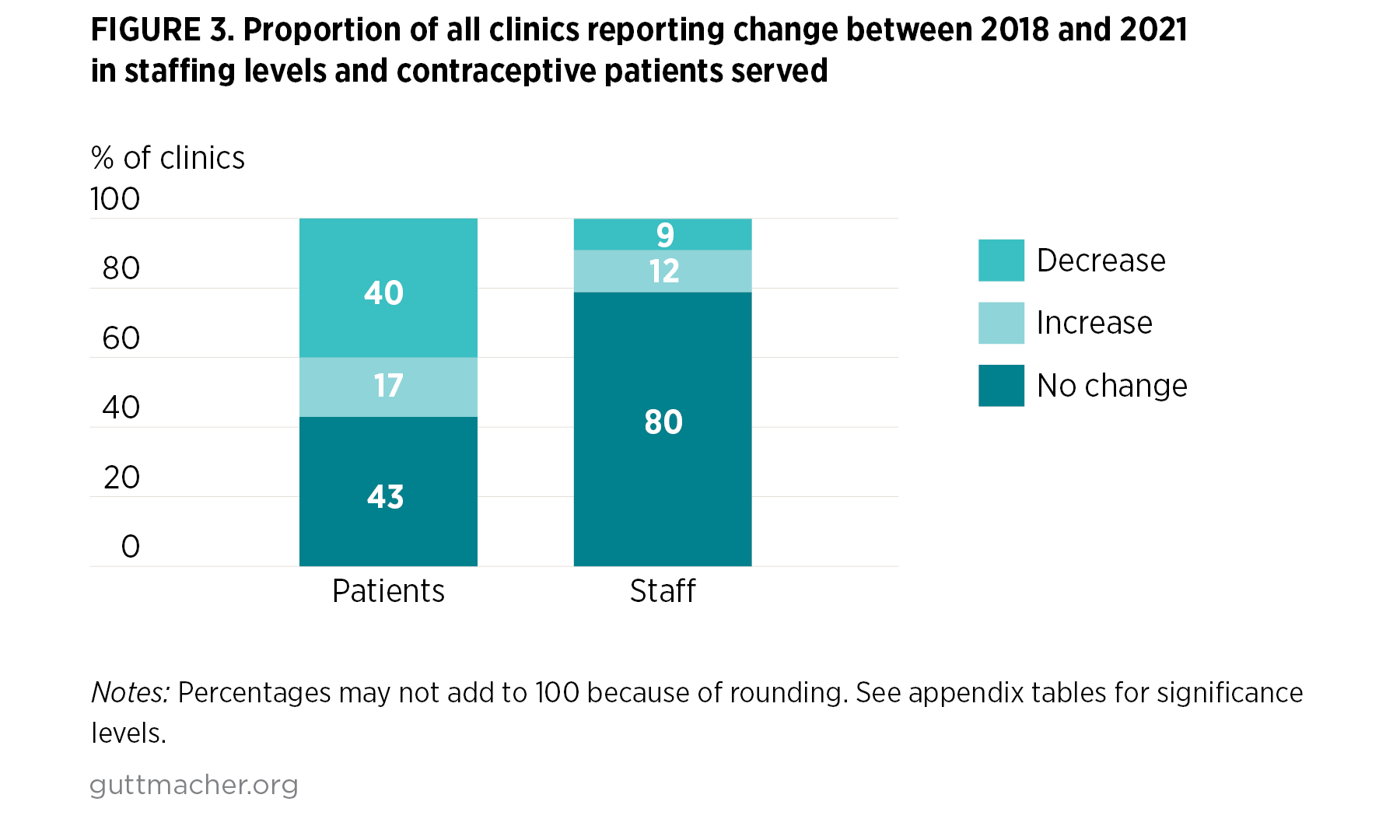

Perceived changes in patient volume and clinic staff

Respondents to the Wave 2 survey answered a series of questions about changes that had occurred between 2018 and 2021 in contraceptive patient volume and clinic staffing.

- More than 80% of respondents reported that the number of contraceptive patients served had either decreased (40%) or stayed the same (43%) between 2018 and 2021 (Figure 3). Only 17% reported an increase in patients over the period. There were no differences based on Title X status.

- At most clinics (80%), respondents reported that the number of staff providing contraceptive services stayed the same between 2018 and 2021; 12% of respondents reported an increase in staff over the period and 9% reported a decrease. A slightly higher, though not statistically significant, proportion of sites that left the Title X program reported that staffing numbers had stayed the same, compared with sites that stayed in Title X (87% vs. 76%).

- None of the clinics that left the Title X program reported an increase in the number of staff providing contraceptive services over the period. In contrast, 16% of clinics that stayed in the program reported an increase in staff providing contraceptive services.

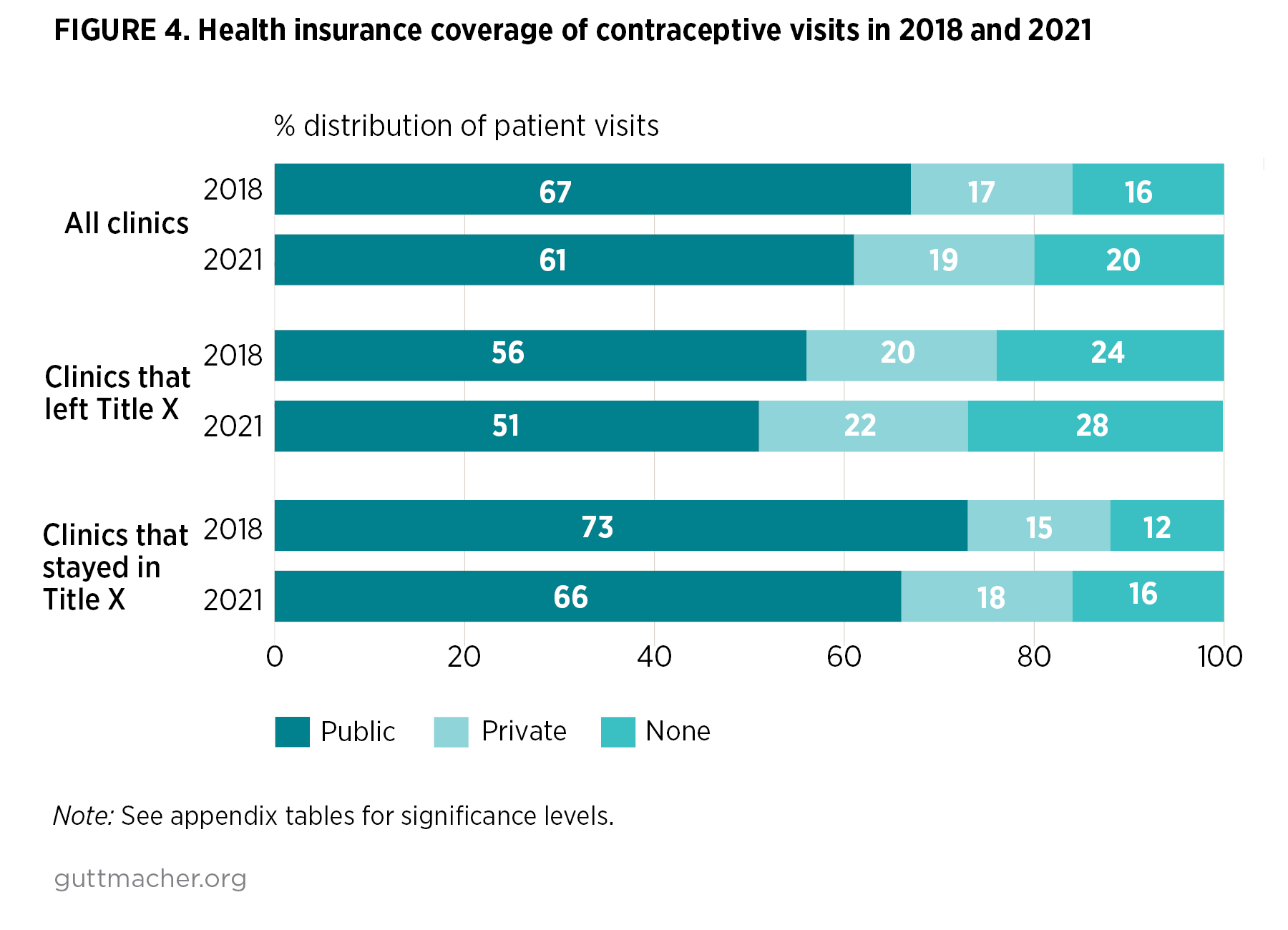

Insurance coverage for contraceptive visits

Providers reported that the highest proportions of contraceptive patient visits at their clinics were covered by public insurance in both 2018 and 2021.

- Higher proportions of contraceptive visits were covered by public health insurance at clinics that stayed in the Title X program (73% in 2018 and 66% in 2021; Figure 4) than at clinics that left the Title X program (56% in 2018 and 51% in 2021). Similarly, lower proportions of visits were not covered by any insurance at clinics that stayed in Title X (12% in 2018 and 16% in 2021), compared with the proportions of visits at clinics that left the program (24% in 2018 and 28% in 2021).

- Between 2018 and 2021, there were no significant changes in the proportions of visits covered by different insurance types at both types of clinics.

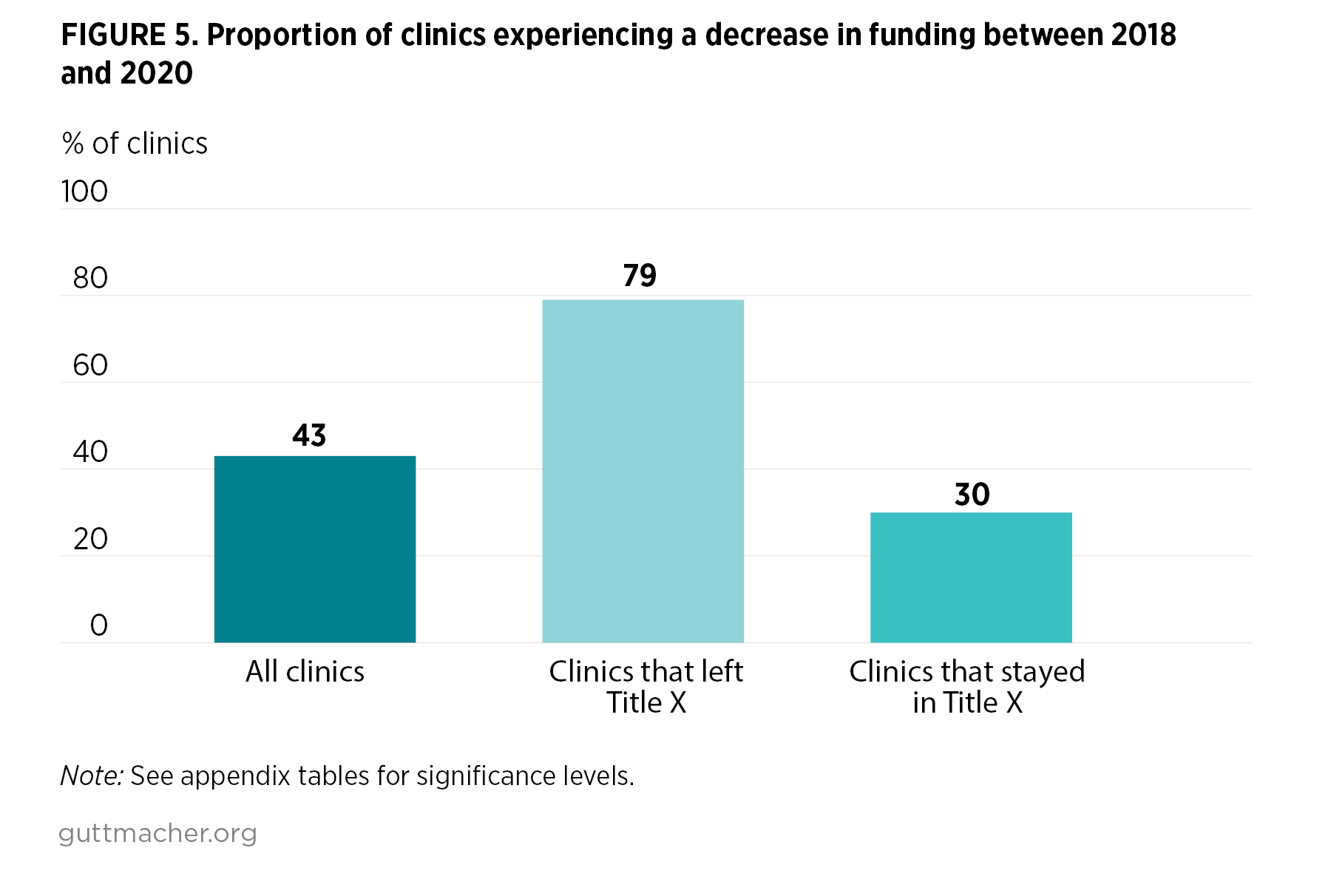

Funding changes

Respondents to the Wave 2 survey were asked whether they had received funding from specific sources to support the provision of family planning services as part of their 2020 fiscal year budget. For each source, they were also asked whether the amount of funding had increased, decreased or stayed the same, compared with the funding in their 2018 fiscal year budget.

- Forty-three percent of respondents reported a decrease in one or more of the funding sources between 2018 and 2020 (Figure 5).

- Nearly four in five (79%) clinics that had left the Title X program reported cuts to at least one source, whereas fewer than one-third (30%) of clinics that continued to participate in Title X reported decreases in funding.

- None of the clinics that stayed in the Title X program reported that their Title X funding had decreased between 2018 and 2021. However, 17% of these sites reported a decrease in funding from Medicaid.

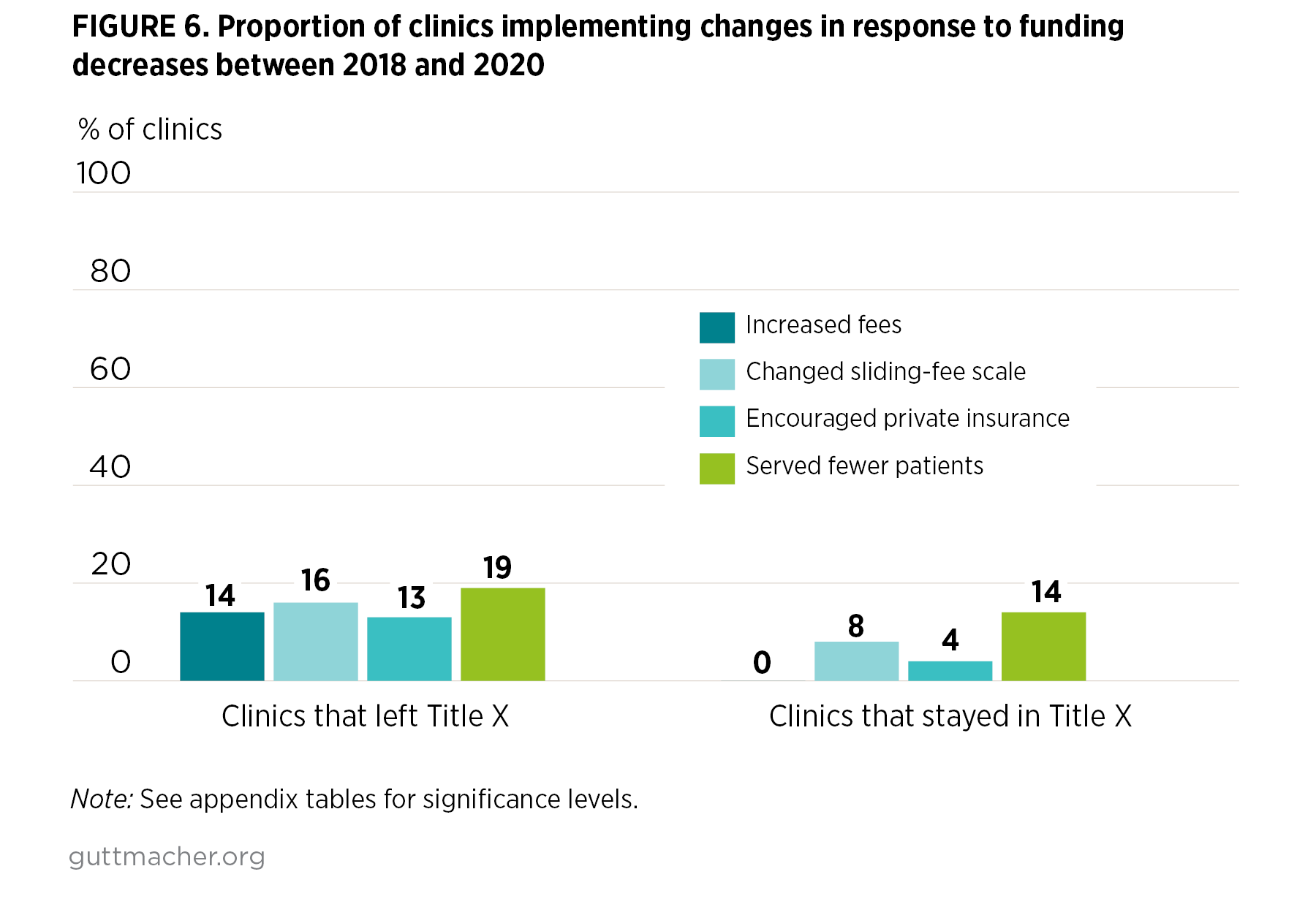

Clinics reported a variety of strategies for dealing with decreases in funding.

- Overall, 16% of clinics reported that funding cuts led them to serve fewer contraceptive patients.

- Clinics also reported changing their sliding-fee scale (11%), encouraging patients to use private insurance (6%) and increasing fees for specific services (4%).

- A higher proportion of clinics that left Title X reported encouraging patients to use private insurance (13% vs. 4%) and increasing fees for specific services (14% vs. 0%), compared with sites that remained in the program (Figure 6).

Clinic challenges

Respondents in both waves were asked an open-ended question about the top three challenges currently facing their clinic. In Wave 1, the most prevalent challenges reported were funding or billing issues, staff issues and patient volume (data not shown).

The most commonly reported challenge among all sites in Wave 1 was funding or billing-related issues. This challenge was much more common among the group that left the Title X program compared to clinics that stayed in the program. For these clinics, “loss of Title X [funding]” was the most common write-in answer.

As one respondent explained:

“Patients were accustomed to a very streamlined experience where their services were simply covered without complication or extensive paperwork; this is no longer the case in the absence of Title X, and some patients are resistant to the increased work of applying for [the state family planning waiver program]. There also seems to be a considerable challenge for patients when it comes to doing the required [follow-up] with the state. This breakdown in the process leads to a lapse in coverage for the patient.”

Clinics that stayed in Title X and noted funding or billing challenges in Wave 1 described challenges related to the program, such as “navigating the Title X regulation and data burden” and dealing with billing requirements.

Staff-related concerns were cited by many clinics as a top challenge in Wave 1. The types of staffing issues reported were similar between those that stayed in Title X and those that left. Respondents highlighted challenges related to staff turnover, staff morale and difficulties maintaining appropriate staffing levels.

As a respondent from a site that left Title X said:

“Staff morale is often a challenge, as we see increased patient volumes and a higher percentage of patients without any [insurance] coverage or without stable coverage. Higher rates of upset patients, increased workload and a hostile political environment can make staff feel like they are frequently under attack just for doing what they believe in.”

Other commonly reported challenges in Wave 1 were related to patient volume and community outreach. These were sometimes related to low numbers of patients, such as “patient growth rate is slow” and “low client numbers.” However, some sites also mentioned increasing numbers of patients as a challenge, while others highlighted unpredictability as a key concern, such as the “show rate” for appointments or the challenge of managing walk-in appointments. Challenges related to community outreach centered on marketing or advertising for the clinic and “lack of community knowledge about our services.”

Some of the most commonly reported challenges in Wave 2 were different from those reported in Wave 1. Concerns regarding staff morale and retention remained common in Wave 2. However, in Wave 2, many respondents also mentioned ”staff shortages.” The increase in staffing concerns likely resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, as respondents described the challenges associated with exposure to the virus, as well as increased staff burnout. For example, one respondent said: “[The] number of patients remains the same or increasing, but staff have illness or day-care absences, leaving them away from [the] clinic and [their] duties falling on others.”

Challenges related to patient volume were also more commonly reported in Wave 2 than in Wave 1. This was reported more often among sites that left Title X, compared with sites that stayed in the program. As they did in Wave 1, clinics reporting these challenges in Wave 2 mentioned difficulties with no-shows, walk-ins and clinic flow. One respondent said that their site struggled with the “volume of walk-in visits,” which leads to “no previsit planning in this location.” Another challenge mentioned in Wave 2 was “appointment availability,” which several respondents related to staffing shortages. As one respondent explained, “seeing patients in a timely manner” was a top challenge.

As a result of the timing of the two waves, COVID-related concerns were more commonly reported in Wave 2 than the proportions reported in Wave 1. Data collection in Wave 1 began prior to the pandemic and was completed by April 2020, before COVID-19 spread widely across the United States.

Challenges related to COVID-19 in Wave 2 included cost and supply issues with stocking personal protective equipment, patients avoiding routine health care as a result of the pandemic (e.g., “people are unsure of going to any health care office due to COVID worries”) and the difficulty of prioritizing family planning services amidst COVID-19 care (e.g., “staff still working with the COVID response in our P[ublic] H[ealth] Department”).

Discussion

This report sheds light on how the Trump administration’s gag rule, which overlapped with the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, affected clinics participating in the Title X family planning program in Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin. While the sample size of 96 sites across four states is relatively small, our findings show both similarities and differences between clinics that left the Title X program in the wake of the domestic gag rule in 2019 and those that continued to participate in Title X.

Contraceptive services and pregnancy counseling at clinics that left Title X and those that stayed

The proportion of clinics overall that provided comprehensive contraceptive and pregnancy counseling fell between 2018 and 2021, likely as a result of the gag rule. There were differences for specific types of counseling between clinics that left Title X and those that stayed in the program.

Most clinics that left Title X continued to offer the full range of contraceptive options. Notably, among sites that stayed in the Title X program, the proportion offering counseling on the full range of contraceptive options declined, while most sites that left the program continued to offer such counseling. This pattern may reflect the gag rule’s emphasis on FABMs and removal of requirements that participating sites offer a broad range of methods. Interestingly, provision of FABMs increased more among sites that left Title X than those that stayed in the program, even though the gag rule mandated that these methods be included in the definition of contraception. This may indicate a lack of resources for sites that remained in Title X or the low priority placed on increasing availability of FABMs amid the COVID-19 pandemic disruption. It is also possible that sites that left Title X were planning to increase FABM access regardless of the gag rule to support patient access to their preferred methods.

Nondirective counseling declined in both types of clinics. There was a slight decline in the proportion of sites providing nondirective counseling on options for pregnant patients among both sites that left Title X and those that stayed in the program. Sites left Title X in the wake of the gag rule in part because of the requirement that they stop counseling patients on accessing an abortion and no longer refer patients seeking abortions to appropriate providers, as well as the onerous requirements of physical and financial separation of Title X–funded services from abortion care.2 Sites that left the program were not required to comply with the updated Title X regulations, yet about 10% of these sites reported no longer offering nondirective pregnancy options counseling in 2021. This may indicate that the gag rule had a chilling effect on counseling practices regardless of a site’s Title X status.

A high percentage of sites that remained in Title X (82%) reported that they continued offering nondirective counseling even though they were no longer legally able to refer or provide counseling on abortion, which may indicate that sites interpreted “nondirective” to mean allowing the patient to decide whether to have an abortion, regardless of whether the clinic had practices in place to support access to abortion care.

Overall, our findings regarding contraceptive method availability reflect the underlying differences between the composition of clinics that left and stayed in Title X. Clinics that left the program were more often specialized reproductive health centers, such as Planned Parenthood clinics, that have historically offered a robust package of contraceptive methods and services, while those that stayed in Title X were predominantly health departments, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and hospitals or other sites, many of which offer contraceptive services as part of a broader package of primary care or public health services.7 As a result, it was not surprising to find that clinics that left Title X continued to offer LARC methods, as well as counseling on a full range of contraceptive options, at higher rates than sites that stayed in Title X.

Other changes at both types of clinics

More clinics in both groups began offering primary care services. In terms of other health services, there was a sizeable increase in the proportion of clinics in both groups providing primary care services between 2018 and 2021. This may demonstrate a shift in priorities among providers in general toward offering a broader package of care. However, it is also possible that respondents in 2021 included COVID-19–related services in their definition of primary care, and the increase did not necessarily mean that many sites had greatly expanded their primary care offerings. Future research should investigate if the proportion of sites reporting primary care provision remains high even as the pandemic subsides, and it might be worthwhile to include an item on COVID-19 services in addition to primary care in future surveys. At the same time, provision of some related sexual and reproductive health services fell over the period, potentially reflecting resource constraints, especially among sites that left the Title X program. For example, the share of clinics offering colposcopies fell among those clinics that left the Title X program, but not among sites that stayed in Title X. A similar pattern was found for provision of expedited partner therapy for STIs.

Both types of clinics served fewer patients. Over the study period, four in 10 clinics reported a decrease in the number of contraceptive patients served, and the reported average weekly contraceptive caseload fell by 45%. These changes are due in part to the impact of the pandemic,8 and they affected both clinics that stayed in the Title X program as well as those that left the program. For clinics that left Title X, some of the decrease in patients served is likely a result of the funding disruptions they experienced, but it is difficult to untangle the specific causes. Dealing with unpredictable patient loads was also a commonly reported challenge in the open-ended responses from surveyed sites.

Funding challenges were clearly disruptive for clinics that left Title X. Nearly eight in 10 clinics that left Title X reported a decrease in funding from one or more sources between 2018 and 2021 (compared with only 30% of clinics that stayed in the program), and these sites were more likely to report that funding cuts led to changes to the sliding-fee structure or increased fees for some services. Such changes may have resulted in some patients choosing not to return to their preferred provider but to seek care elsewhere. Increased turnover in the places people sought contraceptive care over this period may have occurred as patients’ health insurance shifted.

There was a slight decline in the proportion of patients who were covered by public insurance in our study. This may have occurred for many reasons, including changes in who chose to seek contraceptive care during the COVID-19 pandemic years and movement of some patients to seek care from private providers willing to accept public insurance. In addition, changes to people’s insurance status as a result of job losses or other pandemic impacts may have changed the composition of patients seeking care from clinics, putting further strain on these sites as the share of uninsured patients increased.

Exploring the responses to the open-ended survey question, asked in both 2018 and 2021, about the top three challenges facing their clinic deepens our understanding of how both the gag rule and the COVID-19 pandemic affected service delivery. Clinics reported strains as a result of staffing challenges; sites that left the Title X program were more likely than those that stayed in the program to report losing staff over this period. Sites that left also reported staff retention and morale as the most important challenges they faced in 2021. These challenges were likely exacerbated by the pandemic, which increased stress and burnout among health care workers overall.

Conclusion

Publicly funded family clinics in the four states studied experienced a variety of disruptions and reported numerous challenges between 2018 and 2021 as a result of the domestic gag rule and COVID-19. Future research should examine the impact of policy change on service provision and the ability of providers to restore these services when resources are restored.

Methodology Appendix

This study is one of many components of the Guttmacher Institute’s larger Reproductive Health Impact Study (RHIS). The aim of RHIS is to measure the impact of policy disruptions in publicly funded family planning care between 2017 and 2022. For this study, we conducted a survey with family planning clinics in Arizona, Iowa, New Jersey and Wisconsin. We received responses from health departments, hospitals, specialized sexual and reproductive health care centers, federally qualified health centers and lookalikes, and other health care facilities. We conducted the survey in two waves. Wave 1 was conducted between September 2019 and April 2020, and collected data on 2018; initially, all known publicly funded family planning providers in the four study states were contacted to request their participation regardless of Title X status (n=600). Because the COVID-19 pandemic developed during our initial fielding period, the study team discontinued recruitment of clinics that were not Title X recipients in 2018, leaving a sample of 175 clinics. This yielded 109 respondent sites, a response rate of 62%.

Wave 2 was conducted between January and June 2022 with the 109 sites who received Title X funding in 2018 and completed Wave 1. In Wave 2, we asked about two time periods in most of the questions—early in the COVID-19 outbreak (July–December 2020) and later in the pandemic (November–December 2021); in most cases, we pooled the responses to these two time points to yield one estimate for Wave 2. There were nine sites that did not complete the Wave 2 questionnaire. In addition, four clinics had closed or discontinued their services since Wave 1, yielding a final sample of 96 sites. The number of observations reported in tables and figures may vary as a result of missing data.

An online survey was created using REDCap for both waves of the study. None of the survey questions were mandatory, and any could be skipped. In exchange for their participation, participants received a $50 gift card. Since the study involved gathering information about professional obligations of administrators and medical providers, the study was deemed exempt from review by the chair of the Guttmacher Institute’s Institutional Review Board.

We asked respondents about site characteristics; the average number of weekly contraceptive patients they served and hours they were open; the contraceptive methods and sexual and reproductive health services provided; patients’ insurance coverage; types of funding the site received; changes to funding sources; and changes in numbers of patients and staff. In addition, respondents were asked whether their clinics had adjusted their services to accommodate changes caused by funding shifts, such as higher patient volumes or different service delivery methods. Respondents were also asked to describe the three main challenges that faced their clinics in an open-ended question.

A statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 17. The data were weighted for sampling ratios and response rates to reflect the universe of family planning providers at the time the sample was drawn. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Comparisons between waves by key characteristics have been tested for significance using linear regressions and chi-square tests. Open-ended responses were reviewed to develop thematic categories, and responses were then sorted into categories to assess how commonly reported each theme was at each wave.

This study has several limitations that are important to keep in mind when interpreting the results. Notably, the small sample size and focus on four states means that results should not be considered generalizable to all family planning clinics across the United States, given, for example, the possibility for state-level policy differences to influence contraceptive provision. Because Wave 1 of this study was designed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, we initially planned to incorporate findings from non-Title X sites as well. However, we decided to exclude them from our sample after we had begun the first round of data collection because of the disproportionate impact we expected the pandemic might have on sites that focus more on primary care provision than on family planning. Thus, our findings should not be used to understand how sites that never participated in Title X were affected by the gag rule or by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the timing of our Wave 1 data collection meant that some surveys were received prior to the inception of the pandemic, while others were received as COVID-19 was beginning to spread around the country. Finally, although our survey questions specified the time period of interest, respondents may have conflated the situation at the time of data collection with the period of interest.

Appendix Tables to Figures 1, 3–6

References

1. Hasstedt K, Shoring up reproductive autonomy: Title X’s foundational role, Guttmacher Policy Review, 2019, 22:37−40, https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2019/07/shoring-reproductive-autonomy-ti….

2. Dawson R, Trump Administration’s Domestic Gag Rule Has Slashed the Title X Network’s Capacity by Half, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2020, https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2020/02/trump-administrations-domest….

3. Frost JJ, Mueller J and Pleasure ZH, Trends and Differentials in Receipt of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in the United States: Services Received and Sources of Care, 2006–2019, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2021, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/sexual-reproductive-health-services-i….

4. Dawson R and Hasstedt K, Title X Under Attack—Our Comprehensive Guide, New York: Guttmacher Institute, Updated 2021, https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/03/title-x-under-attack-our-com….

5. Fowler CI, Gable J and Lasater B, Family Planning Annual Report: 2020 National Summary, Washington, DC: Office of Population Affairs, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2021, https://opa.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/title-x-fpar-2020-natio….

6. Guttmacher Institute, Reproductive Health Impact Study, 2022, https://www.guttmacher.org/reproductive-health-impact-study.

7. Zolna MR and Frost JJ, Publicly Funded Family Planning Clinics in 2015: Patterns and Trends in Service Delivery Practices and Protocols, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2016, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-funded-family-planning-clini….

8. Mueller J et al., Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on publicly supported clinics providing contraceptive services in four US states, manuscript, 2023.

Suggested Citation

VandeVusse A et al., Publicly Funded Clinics Providing Contraceptive Services in Four US States: The Disruptions of the “Domestic Gag Rule” and COVID-19, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2023, https://www.guttmacher.org/report/clinics-providing-services-in-four-us….

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the clinic staff who completed surveys, without whom this study would not have been possible, as well as those who provided feedback on drafts of the survey. In addition, we are grateful for critical feedback and contributions from the following current or former colleagues at the Guttmacher Institute: Joerg Dreweke, Matthew Johnson, Megan Kavanaugh, Anqa Khan, Ellie Leong, Meg Schurr, Emma Stoskopf-Ehrlich and Patrice Williams. This report was edited by Peter Ephross and Chris Olah.

This study was made possible by a grant to the Guttmacher Institute from an anonymous donor and by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions and policies of the donors. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the report.